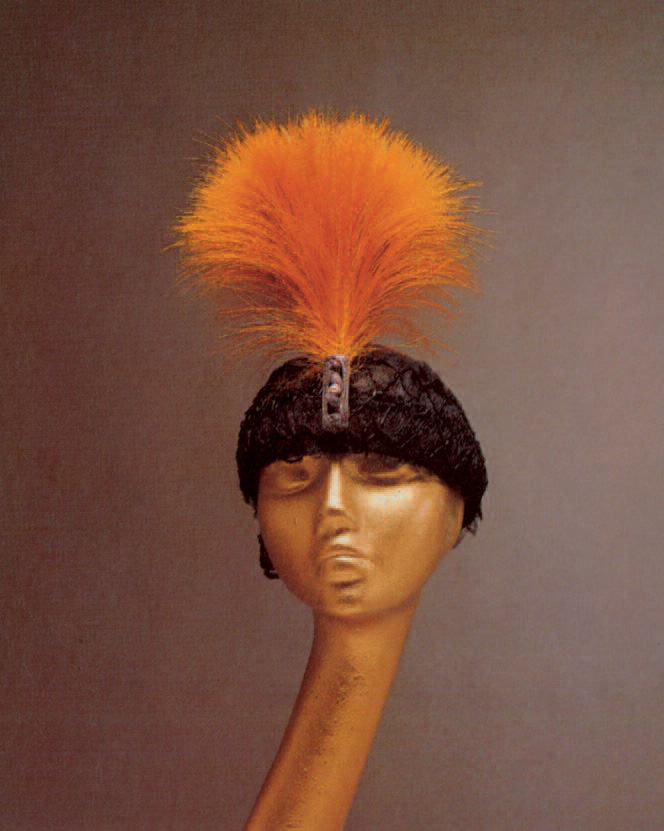

How can a woman’s hat made in New York City (ca. 1915) and decorated with iridescent bird of paradise plumes from New Guinea affect our understanding of history? What relationships were responsible for its creation? What do such relationships reveal about New Guinea and its connections to the rest of the world? How might the characteristics of a natural species like the greater bird of paradise influence human history? These questions arose while I was conducting ethnographic research in the lowland interior rain forests of southern New Guinea among the Yonggom people. The answers challenge how we think about history, including the commonly held view of New Guinea as a remote island that has remained isolated from the tides and currents of world historic.

The Effects of Colonialism and the Height of Fashion

During the first two decades of the 20th century, hats decorated with bird feathers were in style among women living in the cosmopolitan centers of Europe and the Americas. Feathers imported from the tropics were the most desirable, perhaps none more so than the brilliant plumes of birds of paradise from New Guinea and the Moluccas. From 1905 to 1920, 30,000–80,000 bird of paradise skins were exported annually to the feather auctions of London, Paris, and Amsterdam. This demand for bird of paradise plumes inspired Malay, Chinese, and Australian hunters to seek their fortunes in New Guinea’s rain forests. One of several important hunting grounds during the international “plume boom” was the area between the OkTedi and Muyu Rivers where the Yonggom people live.

Amitav Ghosh’s historical travelogue, In an Antique Land (1992), describes how European expansion into the Indian Ocean during the 16th and 17th centuries gradually erased the memory of earlier movements of people and goods between Northeast Africa and India’s Malabar Coast. This is a common consequence of colonialism that prior connections and histories are forgotten. Colonial intervention has similarly affected the historical knowledge of New Guinea, limiting what we remember about the international trade in bird of paradise feathers. While hats decorated with bird of paradise plumes can still be found in museums and attics, we no longer recall the details of the long-distance trade networks that previously connected the rain forests of New Guinea to the fashion capitals of the world.

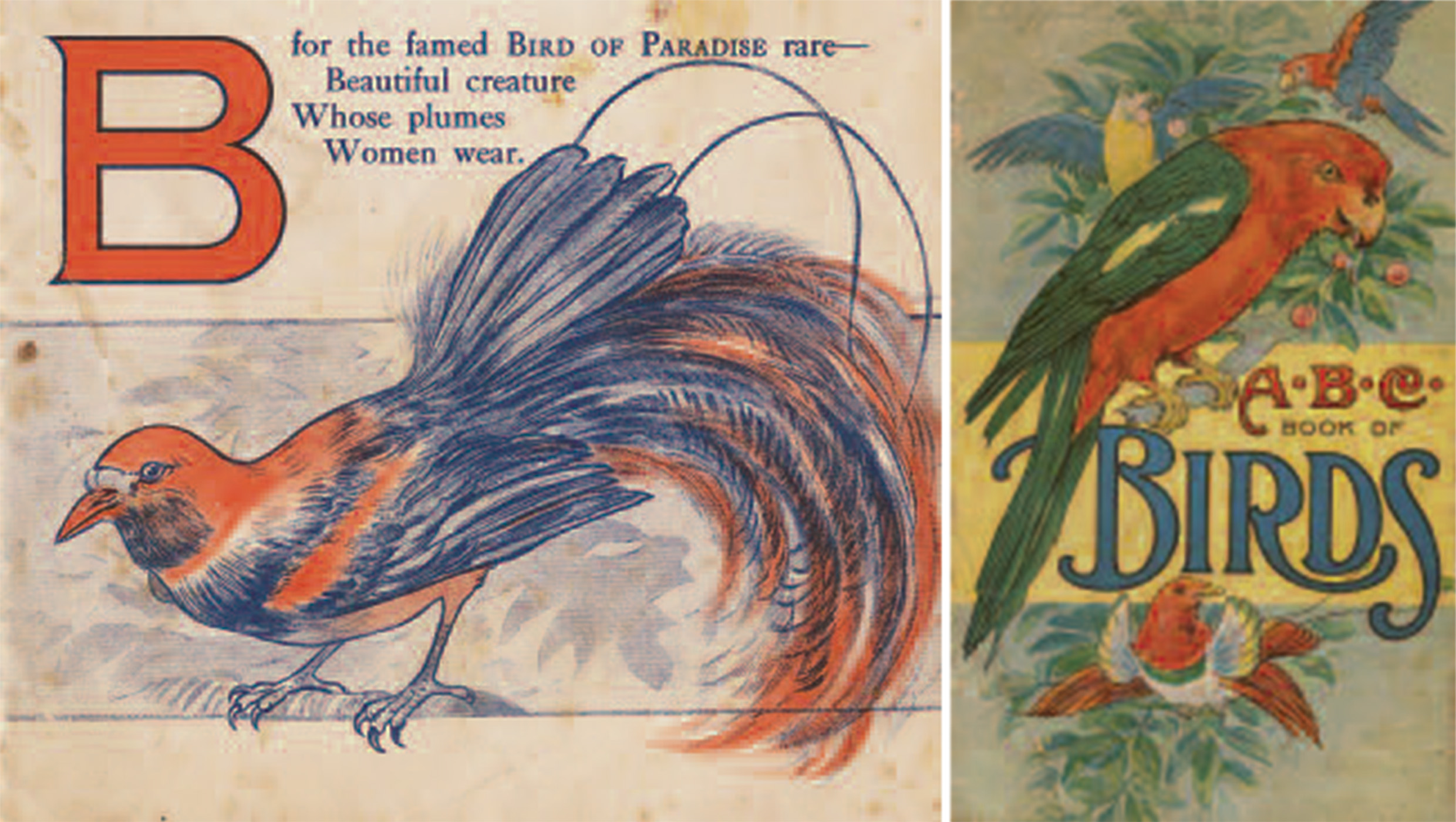

Birds of paradise have been the focus of scientific curiosity and aesthetic desire in Europe since 1522, when the only ship to complete Magellan’s circumnavigation of the world returned with five skins of the lesser bird of paradise along with its cargo of cloves. Portuguese sailors later brought bird of paradise skins from the Moluccas (Indonesia) back to Europe. Their richly colored plumes captivated European imaginations, as did their unusual anatomic, for the legs of the birds had been removed during their preservation. This gave rise to European speculation that the birds, unable to alight, must remain perpetually in flight, suspended between heaven and earth. When Linnaeus published the first scientific description of the Greater Bird of Paradise in 1758, he invoked the bird’s initial reception in Europe by naming the species Paradisea apoda, the “footless” bird of paradise.

In 1857, Alfred R. Wallace published the first scientific description mating practices of the bird of Paradise in The Annals and Magazine of Natural History, in May and June they have mostly arrived at their full perfection. This is probably the season of pairing. They are in a state of excitement and incessant activity, and the males assemble together to exercise, dress and display their magnificent plumage. For this purpose they prefer certain lefty, large-leaved forest-trees (which at this time have no fruit), and on these, early in the morning, from ten to twenty full-plumaged birds assemble, as the natives express it, “to play and dance.” They open their wings, stretch out their necks, shake their bodies, and keep the long golden plumes opened and vibrating constantly changing their positions, flying across and across each other from branch to branch, and appearing proud of their activity and beauty. The long, downy, golden feathers are, however, displayed in a manner which has, I believe, been hitherto quite unknown, but in which alone the bird can be seen to full advantage, and claim our admiration as the most beautiful of all the beautiful winged forms which adorn the earth. Instead of hanging down on each side of the bird, and being almost confounded with the tail (as I believe always hitherto represented, and as they are, in fact, carried during repose and flight), they are erected vertically over the back from under and behind the wing, and there opened and spread out in a fan-like mass, completely overshadowing the whole bird. The effect of this is inexpressibly beautiful. The large, ungainly legs are no longer a deformity as the bird crouches upon them, the dark brown body and wings form but a central support to the splendour above, from which more brilliant colours would distract our attention, while the pale yellow head, swelling throat of rich metallic green, and bright golden eye, give vivacity and life to the whole figure. Above rise the intensely-shining, orange-coloured plumes, richly marked with a stripe of deep red, and opening out with the most perfect regularity into broad, waving feathers of airy down, every filament which terminates them distinct, yet waving and curving and closing upon each other with the vibratory motion the bird gives them; while the two immensely long filaments of the tail hang in graceful curves below.

Europeans knew little about the behavior and biology of the birds of paradise until 19th century voyages of exploration made it possible to carry out first-hand observations of the birds in the wild and to make scientific collections of specimens. Among the naturalists who studied New Guinea’s birds of paradise was Alfred R. Wallace, who produced the first scientific description of their mating practices. Charles Darwin may well have been thinking of them when writing about sexual selection in The Descent ofMan and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871): “When we behold a male bird displaying his graceful plumes or splendid colours before the female … it is impossible to doubt that she admires the beauty of her male partner.”

First Contact Along the Oktedi River

Scientific interest in the birds of paradise was responsible for the events of first contact between Europeans and the Yonggom. During an expedition to New Guinea’s west coast in 1873, the Italian explorer and naturalist Luigi D’Albertis identified a new bird of paradise species with ruddy plumes, which he named Paradisaea raggiana after his friend the Marquis Raggi of Genoa. The interest generated by his discovery enabled D’Albertis to raise funds for two more expeditions, including the longest river journey into the island’s unexplored southern interior.

In 1876, D’Albertis and his crew followed the Fly River north for five weeks, traveling about 580 miles upstream, until it became too shallow for the steamship Neva to continue. On his return journey, D’Albertis ordered the crew to turn the ship up the OkTedi River, a tributary of the Flay. On the evening of July 4, the Neva anchored beside a small island in the lower OkTedi River. The following morning, a group of Yonggom men appeared on the western shore, staring at the ship with curiosity. Exhausted from the long journey and ill with fever, D’Albertis sat on board and peered back at them through his binoculars. Suddenly one of the Yonggom men turned away from the ship and slapped the back of his thigh. Correctly interpreting the gesture as an insult, the temperamental D’Albertis erupted in anger. The men disappeared into the forest, but when they returned for another look, D’Albertis ordered his reluctant engineer, Lawrence Hargrave, to fire an exploding rocket over their heads.

In his two-volume account of his expeditions to New Guinea, D’Albertis described seeing five birds of paradise fly across the OkTedi River. “The last rays of sun gilded the long yellow feathers of their sides for an instant. Never until today have I been able to contemplate the magnificence of this bird [in flight].” The following day the crew of the Neva returned from a foray into the rain forest with a “magnificent specimen of Paradisaea apoda, the greater bird of paradise.” Although D’Albertis’s expedition along the Fly River claimed its legitimacy in terms of scientific discover, it paved the way for commerce. Several decades later the first bird of paradise hunters followed D’Albertis’s path to the area between the OkTedi and Muyu Rivers.

The Yonggom and the Bird of Paradise Hunters

The Yonggom called the hunters ono dapit, from ono, their name for the greater bird of paradise, and dapit, which referred to the light color of the hunters’ skin. The name ono dapit was still occasionally used to refer to Euro-Americans during the 1980s. The hunters established camps near Yonggom settlements and engaged local guides to take them hunting, providing steel axes and knives in exchange for the birds they killed. These tools were highly valued by the Yonggom because they reduced the labor involved in clearing trees for gardens and building houses. The hunters also traded tobacco and white porcelain beads for food. Yonggom stories about the bird of paradise hunters depict these interactions in a positive light. Years later, an Australian patrol office attributed the “friendly disposition”of the Yonggom to their familiarity and good relations with the foreign hunters.

The primary bird species hunted in this region was the greater bird of paradise, which has neon yellow and orange tailfeathers. The hunting season ran from April until September, during the bird’s mating season when the males were in full plumage. At this time of year a group of mature males will congregate regularly in an established canopy tree, participating in a communal display of courtship that attracts potential mating partners. The only efficiency strategy for hunting these birds in large numbers is to locate their display trees and wait for the birds to assemble. As Wallace observed, the birds become so immersed in their performance that they become vulnerable to predation by hunters. The success of the foreign hunters was therefore contingent on the cooperation of local residents who could lead them to the display trees located on their land.

The mating patterns of the birds of paradise thus influenced the relationships between the two parties, making the foreign hunters dependent on indigenous knowledge.

By evoking Euro-American interests in science, and later in fashion and commerce, the birds of paradise attracted outsiders to the region, shaped their interactions with the Yonggom and their neighbors, and led to the incorporation of New Guinea into the global economy. In effect, the natural characteristics of this bird and its behavior influenced the course of human historic, including relationships between Euro-Americans and the people of New Guinea.

The Birds of Paradise and Global Environmentalism

New Guinea is sometimes described as “the land that time forgot” because of its remote location and marginal position in the global economy. This characterization ignores the exchange networks that once connected its rain forests to the fashion districts of the West, as well as subsequent demand for its copra (dried coconut), gold, copper, timber, and coffee. The perception that New Guinea was isolated from the rest of the world also implies that events which occurred there had little significance elsewhere. However, the history of the bird of paradise trade suggests otherwise.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, concern about the widespread slaughter of wild birds for the millinery trade led to the establishment of the Society for the Protection of Birds in Great Britain (1889) and from 1896 the organization of local Audubon Societies in the U.S.—precursors to today’s conservation organizations, including the Sierra Club and the modern Audubon Societies. In 1904, Edward VII granted a royal charter to the Society for the Protection of Birds, and two years later his wife, Queen Alexandra, announced that she would no longer wear “osprey feathers,” the generic term for the plumage of rare and exotic birds, including birds of paradise. Although anti-plumage legislation failed in Britain’s House of Commons in 1908, the U.S. passed the Lacey Act in 1913, banning feather imports and establishing an important precedent for the Endangered Species Acts of the 1960s and 70s. Britain passed similar legislation in 1921.

Opposition to the slaughter of wild birds, including New Guinea’s birds of paradise, resulted in unprecedented international cooperation on conservation issues and legislation that eventually curtailed the global trade in bird feathers. This in turn led to the formation of the modern conservation movement—one of the earliest manifestations of global environmentalism—and appropriated, the elevation of the bird of paradise as an international symbol of conservation.

Alternative Understandings: Imagining Difference and Similarity

By paying attention to the relationships responsible for the production of hats decorated with bird of paradise plumes we can suggest alternative understandings of New Guinea’s history. These understandings emphasize interaction and exchange rather than separation and distance, and they highlight the influence of natural species on human history.

What else might we learn from the bird of paradise trade and the use of bird feathers for decoration? Would it be worthwhile to compare Yonggom men who wear these feathers during their dance performances with the women of Paris, London, and New York who wore the same feathers in their hats a century ago? Whereas 20th century artists like Picasso and Giacometti freely borrowed designs from the Pacific and Africa, the images of fashionable Euro-American women and New Guinea dancers have never been juxtaposed. Although the appreciation and use of bird of paradise feathers crossed cultural, gender, and racial lines, the two images have remained separate. Ignoring this similarity helps to perpetuate Euro-American assumptions about the cultural difference, geographical distance, and historical independence of New Guinea. We still think of New Guinea primarily in terms of its cultural differences from the rest of the world, rather than the experiences we share, such as our mutual appreciation of the sublime beauty of bird of paradise plumes. As I suggest in Reverse Anthropology, the people of New Guinea have much to offer contemporary political and environmental debates if we begin by acknowledging the connections between us.

Conservation Internationals

—Bruce M. Beehler, Conservation International (http://www.conservation.org and http://www.cimelanesia.org.pg)

For Further Reading

Beehler, Bruce M. “The Birds of Paradise.” Scientific American 262-6 (1989):116-23.

D’Albertis, Luigi Maria. New Guinea: What I Did and What I Saw. 2nd ed. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1881.

Konrad, Gunter, and Sukarja Somadikarta. “The History of the Discovery of the Birds of Paradise and Courtship of the Greater Bird of Paradise Paradisaea Apoda Novae Guineae.” Irian 4-3 (1975): 12-30.

Price, Jennifer. Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Swadling, Pamela. Plumes from Paradise: Trade Cycles in Outer Southeast Asia and Their Impact on New Guinea and Nearby Islands until 1920. Boroko: Papua New Guinea National Museum in association with Robert Brown and Associates, 1996.

Acknowledgments

This essay is dedicated to the memory of William H. Davenport, former Curator Emeritus of the Oceania Section at the Penn Museum. Thanks to Michael Hathaway for sharing The ABC Book of Birds and to James R. Mathieu for seeing this essay through to fruition.