There was a man called Imlohe, the young man, Gospo, began his story. Imlohe made a very big garden–as big as from here (Umbi) to Angus (three miles away). In the garden Imlohe planted taro, yams, bananas, sugar (cane) and bega (a ‘green’).

There was a woman with a new born baby and two older girls. They were hungry. The two girls went to look for wild yams in the forest. They came to Imlohe’s garden. Imlohe saw them.

“Why did you come here?”, he asked the two girls. The two girls looked at all the food in the garden and said, “We came to get something to eat.”

The two girls cut down a banana first. As they cut, imlos (flints) filled up the intestines of the man, Imlohe. Next the girls cut down some sugar, and again imlos filled up the man’s intestines. Next they dug out some taro root and again imlos gathered in the man’s intestines. Next the girls dug some yams, and again more imlos gathered in the man’s intestines.

The two girls cut down a banana first. As they cut, imlos (flints) filled up the intestines of the man, Imlohe. Next the girls cut down some sugar, and again imlos filled up the man’s intestines. Next they dug out some taro root and again imlos gathered in the man’s intestines. Next the girls dug some yams, and again more imlos gathered in the man’s intestines.

The two girls tied up the food in their twine bags and balanced them on their heads. As they started to leave, Imlohe put his hand in his anus and pulled out an imlo and threw it at a big tree. The tree broke and fell and nearly killed the two girls.

The two girls ran and Imlohe followed. Again he pulled an imlo from his anus and threw it at a tree and the tree broke and fell and nearly killed the girls. Imlohe threw another imlo and another. Each time Imlohe threw an imlo it hit a tree and the tree broke and fell but did not kill the girls.

Finally the girls came to where their mother and baby sister were resting. Close by they met Kukiung (a cassowary) whom they called mother’s-brother. A tree fell very close to Kukiung and nearly killed him. Then Imlohe threw an imlo directly at Kukiung. Kukiung became mad now and rushed at Imlohe and speared him with the long spur on his leg. Imlohe died.

“Where shall we throw Imlohe?” the girls asked their uncle, Kukiung. “Shall we throw him in Miu country?” (to the Northwest). “No,” replied Kukiung.

“Shall we throw him in Kaulong country?” (to the West). “No,” replied Kukiung. “Throw him in Silop,” Kukiung told the two girls. So the girls threw Imlohe over there in Silop.

Gospo paused in his storytelling to relight his homemade cigarette, some smoke-dried native tobacco rolled up in a strip of newspaper which I had given him earlier. He picked up a glowing stick from my fire around which we were sitting, and holding it to the end of his five-inch cigarette he puffed a few times until the newspaper caught fire. He let it burn for a little while, then blew the flames out and puffed happily on the now glowing cigarette. Then he continued,

So you see Jane, that is why there are so many imlos at this one place. Elsewhere you might be able to find one imlo here and one imlo there–these are the imlos which Imlohe threw at the trees as he was chasing the two girls. But only at Silop, where the girls threw Imlohe himself, will you find many imlos. Now when we walk along the road past Silop, we must walk strongly, we must not walk easily and slowly for if we do the imlos are just like the man, Imlohe, and they will kill you and me.

So you see Jane, that is why there are so many imlos at this one place. Elsewhere you might be able to find one imlo here and one imlo there–these are the imlos which Imlohe threw at the trees as he was chasing the two girls. But only at Silop, where the girls threw Imlohe himself, will you find many imlos. Now when we walk along the road past Silop, we must walk strongly, we must not walk easily and slowly for if we do the imlos are just like the man, Imlohe, and they will kill you and me.

However thoroughly an anthropologist plans his expedition, choosing a location providing the maximum opportunities for the investigation he wishes to make, it is quite often due to pure chance that the choice of location proves fortuitous for the unexpected scientific result. Such was the case in the expedition which Ann Chowning and I made to New Britain, in the Territory of New Guinea.*

In the summer of 1962, Ann and I journeyed into the interior of the Passismanua census district of Southwest New Britain to investigate our chances for finding suitable groups of natives for more extensive ethnographic studies the following year. Suitable to us meant several things. First, they should be as uninfluenced by western culture as possible and, most importantly, unmissionized, for we wished to study the native religion as well as other aspects of their aboriginal way of life. Secondly, we hoped to locate two such groups, separated by language and customs, but close enough geographically so that while we conducted independent ethnographic studies, we could be within visiting distance of each other. The fact that we succeeded in our aims during this preliminary expedition into the interior of the Passismanua, was not due entirely to chance. What little information we could gather prior to our survey all indicated that somewhere in this relatively unexplored area there were such peoples as we wished to study.

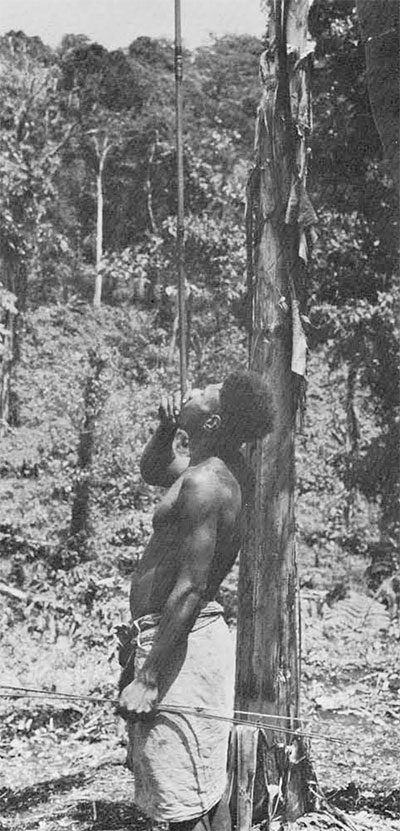

After five days of slogging through the dense forests, on narrow trails which led us up and down one steep limestone ridge after another–endlessly repetitive days–days marked by heavy rains which made mud of the trails and torrents of the rivers, rendering the crossings impossible or fraught with danger due to the increasing swiftness of the streams as we slowly ascended to the foothills of the Whiteman Range, our little expedition led by Patrol Officer, Dave Goodyer, finally reached the Kaulong village of Umbi perched on a ridge of a mountain about twenty-five miles inland from the coast.

I did not exactly “choose” to stay in Umbi–it was a necessity. My feet, unaccustomed to boots, were a mass of open blisters and it was quite impossible for me to continue. However, Umbi from all appearances was at least one of the type of village we were looking for. After a three-day wait for the river Ason to subside enough from the heavy rains for the others to continue, Ann and the rest of the Patrol went on, and a few days later I received a note saying that she was residing in the Sengseng village of Dulago, a day’s walk away from Umbi, and that the Patrol had returned to the post at Kandrian.

The following month each of us coped with the problems of establishing rapport with the people in our respective villages. For me the major problem was to establish communication in its elemental sense. I did not, of course, know their language, and furthermore, I did not know the trade language Pigin-English as this was my first trip to Melanesia. In this Ann was one step ahead, as she had previously worked on the North Coast of New Britain and could speak Pigin. But even she had trouble, for very few of these interior forest people could themselves speak Pigin and those few who could were hardly fluent.

After four weeks, I received a note from Ann saying that she would walk over for a visit. It is hard to express the anticipation I felt. Perhaps the closest I can come is to equate it with the relief one feels after a long bout with laryngitis, the relief at being able to express oneself verbally once more in something better than the monosyllables basic to life.

“Misis i so mei,” “Misis i so men,” I heard the children shout from the path leading up to the village from the river. ‘Misis is coming’ and I hobbled down the path from my house to meet her. Wet, bedraggled, and covered with mud from the usual slips and slides on the muddy trails, and panting from the exertion of the steep climb up from the river, Ann looked exhausted, but more than relief at reaching her destination showed on her face. “Look what I found!” were her first words of greeting. In her hand she held an unmistakable finely worked chipped flint scraper.

Nowhere in any of the literature on New Britain, be it a report of an early explorer, an intrepid missionary, a dedicated Australian Administration official, nor any of the few anthropologists who had studied in New Britain, had there been mention of even so much as one chipped stone tool.

Debli, my cook, came to see what had excited these two strange white Missis, and continuing his language instructions said, “Em, mipela call em imlo. Mipela workim garden long imlo. Mipela workim spear long imlo and planks (shields).”

We got more and more excited. We knew we had been living with people who had had almost no contact with the outside world until a few years previously and who in many ways were extraordinarily unsophisticated even compared with their linguistic brethren elsewhere in Melanesia, but to have them using chipped stone tools put them in a category of “primitiveness” we could not believe. In the following three weeks I was presented with a number of pieces of chert or flint. The vast majority showed no signs of being shaped or used by man, but about half a dozen did, and some were most finely worked. Ann and I left Dulago and Umbi after six weeks and made our way home to plan for our return trip the following June.

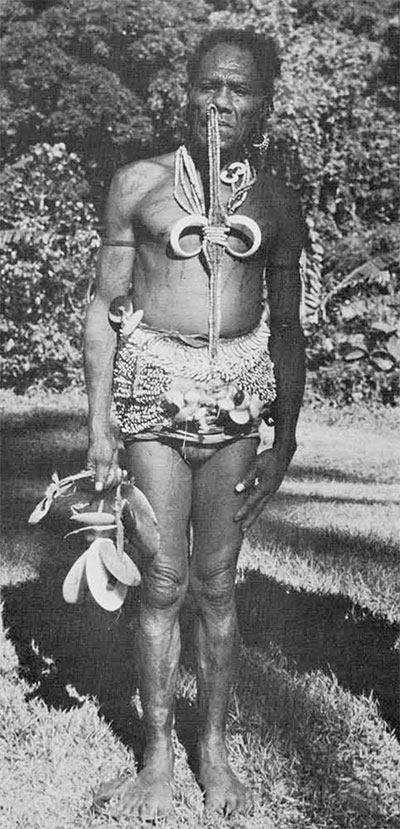

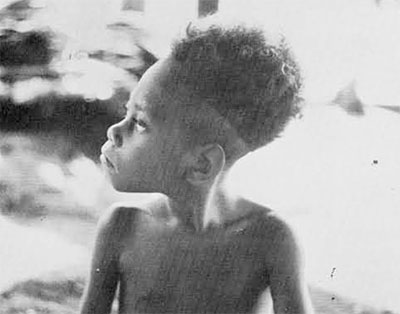

We used the intervening nine months to find out as much as we could of these people with whom we would live for the thirteen month period of June 1963-August 1964. The entire Southwest part of New Britain had long been noted as a culture area where the people practiced a number of unique (to Melanesia) customs. They bound their children’s heads shortly after birth, producing a deformation of extremem elongation of the skull which they considered beautiful. They hunted birds and bats and small arboreal game with sixteen to twenty-foot blowguns made from sections of bamboo bound and glued together with vines and sap. Until pacified a few years ago, they followed a custom of strangling the widow upon the death of her husband and burying them at one time so that they could journey to the mountain-of-the-dead together. In the past, their chief medium of exchange had been polished stone discs, oval in cross section and pierced with a hole, which they told us had been found by their ancestors in the ground. In the interior today, while rarely used for monetary purposes, their place having given way to gold-lip pearl shells, these polished stone discs are still so highly prized that they are hidden from view in the forest, but their possession is equated with prestige and power of the highest order. I know of no outsider who has been able to persuade a native to part with a “mokmok” stone, as they are called. The material from which these mokmoks are made is not native to Southwest New Britain–their origin and age are shrouded in mystery, as are the other unique traits. Now we added another mystery to the area: the origin, age and use of the chipped chert industry.

It wasn’t until I had returned to Umbi and had been there for six months that the young man, Gospo, told me the story of Imlohe one afternoon as we sat under my house keeping dry from the rain and warm by the fire. His story confirmed a growing impression that Ann and I had been discussing. Every month as we exchanged visits, walking between our two villages on a new trail which led past a newly resettled area called Silop, we would stuff our pockets with chipped stone tools. The trail was literally covered with flint, ninety percent of which was unworked chips, flakes, and nodules. It was however easy to spot and collect at least a dozen specimens of the remaining ten percent of worked tools. We continued our questioning of the villagers as to what these tools had been used for and the more we questioned, the hazier and more conflicting the answers became. Our conviction that our present villagers had nothing to do with the manufacture or use of the tools was more firmly established as they brought us in loads of chert indiscriminately collected, containing more unworked chert than worked, once the word went out that we would buy imlos for tobacco. To our companions, imlo meant chert, and it was only after patient explanation that we were able to teach a few of our villagers how to tell if the imlo was a worked tool or not.

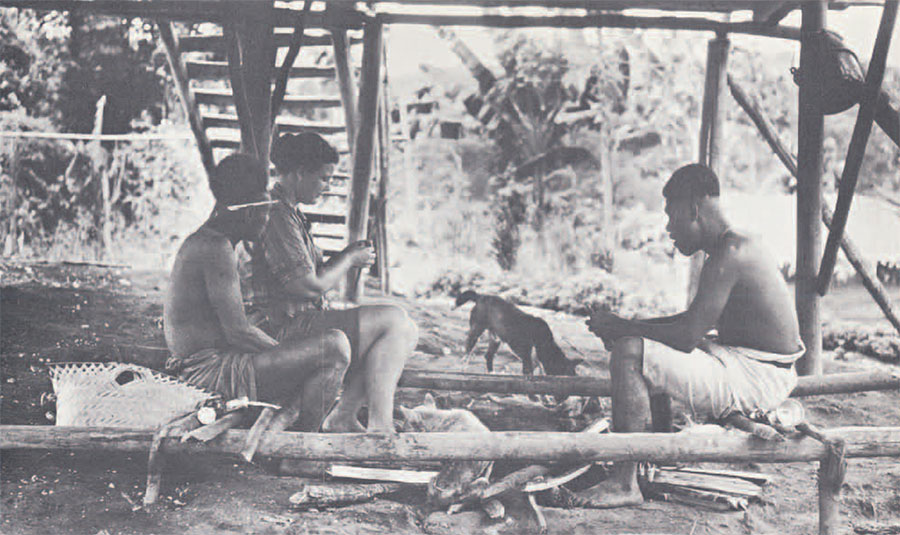

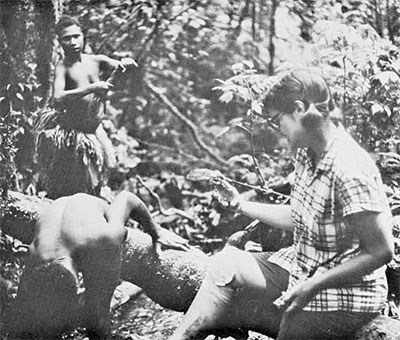

During our daily life in the Umbi and Dulago areas, Ann and I made many trips around the surrounding countryside visiting the people in their scattered gardens where they worked and slept most of their time, visiting the official villages only occasionally. We observed their daily work patterns as they cleared the heavy timber from the garden site, planted it with taro, sugar, bananas, and manioc, built the high, strong, log fences to keep both wild and domestic pigs from ravaging the garden; and then we observed the harvesting and subsequent planting in a newly cleared, newly fenced area, in their endless round of garden activities, required by the poor soil to clear and plant two to three new gardens in a year’s time, never planting in the same spot more than once every five to seven years.

—

Occasionally the clearing of a new garden would result in the discovery of a worked imlo, but they were few and far between. Gospo’s story told us why. Imlohe had been thrown away at Silop, and although a few scattered imlos could be found elsewhere, where Imlohe had thrown them while chasing the girls, there was only one spot in the entire region where they were concentrated–Silop, situated fortuitously halfway between our villages of Umbi and Dulago.

We were now faced with a decision. To further investigate the imlos we should either concentrate our energies in collecting from the surface around Silop or we should look for possible areas for excavation. The limestone ridges characteristic of the are are full of caves which even today are inhabited by a family when they are working a garden close by. In spite of the temptation to drop our ethnographic studies for a while to excavate a cave, we chose to follow the first choice to make an extensive surface collection. This was a matter of expediency: our ethnographic studies were going very slowly and we needed to concentrate on them, we knew that the tools and archaeological sites would not disappear or change with increasing contact as might the people and their way of life. There was therefore no real urgency to excavate. The missions were moving into our area and there was positive evidence that life was changing or would change rapidly in the near future.

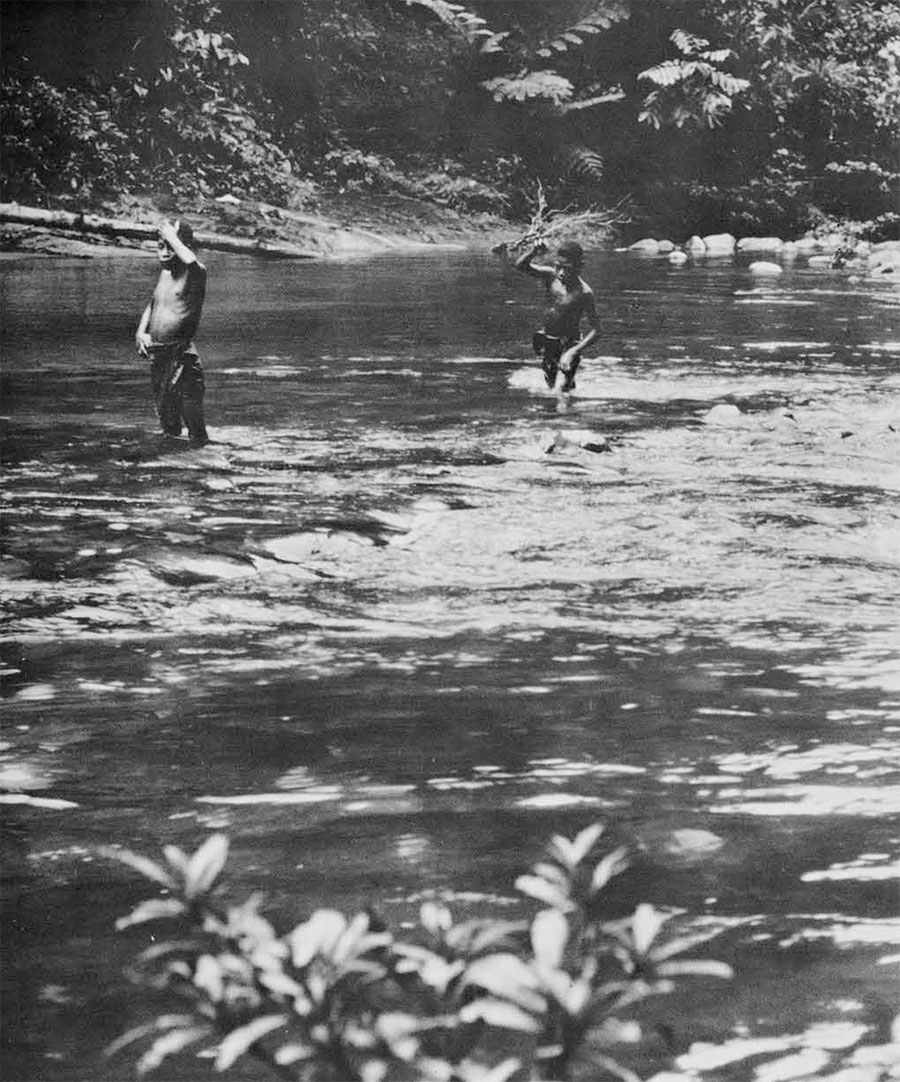

In January, Ann and I planned a concerted investigation of the Silop area to coincide with her trip to Umbi for a visit. I agreed to meet her at the new settlement of Silop at noon and I left Umbi at 8:30 in the morning with two young lads, Lesum and Iamopli as companions. We crossed the Ason River without incident, as during January there is little heavy rain and the river runs quietly and clearly over the rocks. Leaving the river, we began the long ascent up the mountain ridge, following a wide trail which leads diagonally up the mountain, crossing stream after stream, and each time climbing another ridge of the mountain. At the top, after an hour-long climb we reached the huge ficus tree, fully fifteen feet in diameter, which became for me a welcome landmark on my many trips over this trail to Dulago. The three of us caught our wind here sitting on a fallen log and we shared a chocolate bar and some bananas, which restored our energy. From here to Silop the trail was flat and relatively free of obstructions, so that we could stride along without regard to watching every placement of the foot. We could look around and spot the birds flitting through the darkness of the heavy forest. We could, and did, stop to chase an opossum up a tree and try unsuccessfully to dislodge him by shaking the small sapling to which he clung. And we could cast our eyes over the leaf covered trail searching for imlos.

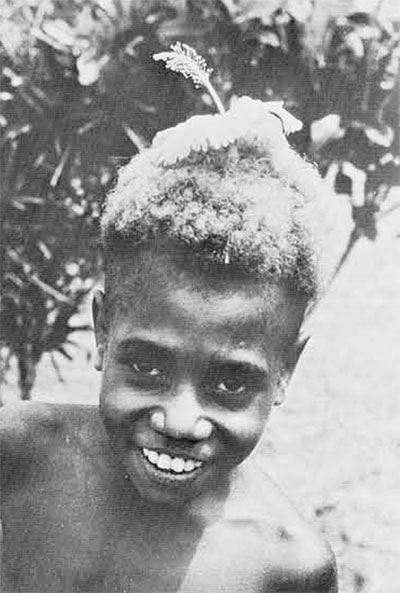

It took us a long time to cover the relatively short distance to Silop, for the two boys were stopping me constantly to show me a piece of chert which they hoped was the kind I was looking for. Lesum produced, among many, two which I felt were worth further consideration, but Iamopli had no such luck and was very discouraged.

The village of Silop was deserted, not unexpected at any time but particularly in the middle of the day. Rather than wait for Ann in the hot sun of the clearing, we decided to go down to the cool shade of the small stream just beyond the village. About halfway down, Iamopli appeared silently by my side and without a word tentatively held up a piece of chert for my inspection. His face held an expression of resignation to the anticipated rejection and he was totally unprepared for my exclamation of pure joy, for this specimen was to become one of the finest examples of a notched scraper in my collection. Jubilantly, we descended to the stream and I broke open my remaining chocolate bar in celebration. We sat on the rocks, our feet dangling in the cool waters, and waited for Ann.

We had not long to wait for soon Ann and her two companions appeared, gingerly making their way down the precipitous opposite bank of the stream. We had barely greeted each other, and the young man and woman accompanying her had just begun to roll their cigarettes, when Lesum appeared with his arms filled with large stones from the stream bed and dumped them in my lap. Impatiently I started to throw them away, for they were not like the imlos we had come here to look for. Then I looked again and saw that these river stones bore unmistakable signs of human workmanship. They were in fact, large, crude core tools, some of which had had flakes removed from both sides, others from one side only, and al were covered with a deep red patina. When I showed them to Ann, she produced a similar one she had found just a few moments previously on the path leading down to the stream. Shortly Iamopli appeared from up the stream equally loaded with artifacts. I could not sit still any longer in the face of this archaeological “goldmine” of a stream, so I set off to hunt for myself. Soon however I was forced to return to pass judgment on the growing piles of core tools which the two boys had made on the bank. Ann too was busy inspecting the finds of her two companions, as she sat astride the fallen tree bridging the stream. It was quite incredible–in half an hour it was obvious that to continue collecting would be foolish, for we already had more than we all could carry back to Umbi.

So now the already complex problem became more so. It appeared we had two major kinds of chipped stone tools. The first were the kind found on the trail and occasionally in the gardens, flakes which were retouched into a variety of shapes, tentatively called by us scrapers, end-scrapers, side-scrapers, steep scrapers, and notched scrapers. Some of these finds could be called knives, but never did we find anything resembling a projectile point. These were all made from a light brown chert, and most were finely retouched. Now we had a second series of heavy crude choppers made from cores, apparently characteristically found in the beds of the streams and covered with red patina. Only occasionally did we find this heavy crude type out of the streams and, conversely, rarely did we find the flake tools in the streams. In spite of the fact that this second series came from stream beds, they did not appear to us to be excessively worn by their immediately previous existence rolling about at the bottom of swift flowing water.

We had long ago given up trying to get valuable information about these stone tools from our informants. It was obvious they or their immediate ancestors had not made them. And we had just learned that they even disclaimed all knowledge of how their fathers or grandfathers had made the polished stone axes which they had used until fairly recently when they were replaced with steel. They said, and after their impatience with us became extreme, we finally accepted, that their ancestors had not made the axes at all, but like the mokmok stones, they had found them in the ground and had used them, only sharpening them if necessary.

We were now faced with the problem of integrating the various stone industries, the polished mokmoks and axes, and the chipped flakes and cores, with each other and with what we could deduce from our ethnographic data about the history of our peoples, the Kaulong and Sengseng, who now live in this area. Everything in our ethnographic data, as far as we have analysed it, points to the fact that the Kaulong and Sengseng (and other linguistic groups in this area) have been here for a very long time. But if they did not make the stone tools, who did? And should the “who” be considered in the singular or plural? Are the chipped stone tools contemporaneous with the polished? At least, the raw material for the chipped industry is native to the region, that of the polished tools is not, and the unmistakable conclusion is that the polished tools were made elsewhere and at some unknown time in the past traded in to the people of the interior.

The Silop site, unique as far as we know to the entire area, is quite obviously a work-site, the abundance of raw material and the discarded unworked flakes together with the finished products all attest to this fat. But who made these tools, when, and why?

Taking up the question of why first, the tools in the chipped industries all appeared to us to be heavy woodworking tools, of the kind one would expect to be necessary and useful to Melanesians engaged in creating magnificent and large works of art from the native woods. The present Kaulong and Sengseng are, to our disappointment, perhaps the least artistic Melanesians ever investigated. The only woodcarving they do is their shields and one would hardly expect such an extensive and varied tool kit to be necessary for shield making, or indeed for any aspect of their life as it is lived today. Could they perhaps have had in the past an enriched cultural life, one which is absolutely unknown and unindicated in their present way of life? Could they, in their past, have been specialists in making chipped flake tools, for which they had no use, but which were valuable to other Melanesians and traded widely? If this is the answer, where were they traded? Such flake tools are not yet reported from other New Britain areas, although reports from other Melanesian areas are coming in.

Another possibility is that this Passismanua area could have been the home of others previous to the arrival of the Kaulong and Sengseng, men whose culture in some ways was more sophisticated than that of those living here now–men who made the chipped scrapers and knives and who used the stone industry in some extensive artistic effort, or engaged in production of these items for trade, or perhaps both. There is, however, no other evidence for the existence of these hypothetical people. The argument runs in circles.

Ann and I left the Passismanua in August 1964. In our possession were over three hundred type specimens of the two chipped stone industries. Knowing that we had done all we could at present, we sent the majority of the collection to archaeologists at the Australian National University where they would be available to anyone wishing to follow up our surface collecting with excavation. We kept in our personal collection sixty specimens to show to archaeologists in this country. On our way home, we compared our collections with those in Sydney from Australian sites, in Singapore with Indonesian material on exhibit in the museum, and in Hawaii we consulted with archaeologists familiar with the Pacific Islands prehistory. Nowhere did we find anything resembling our tools, everywhere we stirred up interest.

The archaeology of Melanesia is just beginning. Recent excavations in the highlands of New Guinea have produced chipped flints in limited number, which from the descriptions appear similar to some of our type specimens. Surface finds have been described from the Solomon Islands, which may resemble some of our types. Just recently, I received a letter from Bill Davenport from Santa Ana in the Solomon Islands, describing a notched flake tool, in shape similar to one of our types but lacking the fine retouching characteristic of ours, which he found in an old man’s basket. His informant told him that his people did not make this tool on Santa Ana, but they were traded in from elsewhere. This man also told Davenport that they used these flakes to cut up pork and for hand-to-hand fighting. Ann and I had not thought of these possible uses for our tools; certainly the Kaulong and Sengseng do both, fight and eat pork, to a fine degree.

Ann has recently returned to the Passismanua for further study of the Sengseng and she writes men that an Australian archaeologist is planning to join her shortly to investigate the Silop area. What is certainly needed now, before any further speculation is made, is to find these industries in a stratified site and, hopefully, with organic material which can give us some relative and absolute dates for the imlos.

I, too, plan to return to the Passismanua to continue my study of the Kaulong peoples. Perhaps when our linguistic and ethnographic data are complete and fully analysed, and correlated (again hopefully) with productive excavations of the Silop site, we shall be a step further in our search for solutions to the historical mysteries of the Passismanua.

In spite of the fact that our notebooks are filled with interesting ethnographic data pertaining to the Kaulong and Sengseng, we are quite convinced that our surface collections of imlos are the most significant result of our year’s work in the interior of Southwest New Britain. It is unromantic, but true, to consider that had it not been for my blisters necessitating the choice of Umbi as one point of reference we might never have stumbled on the resting place of Imlohe, situated on a trail over which Ann and I travelled more than a dozen times as we visited each other in Umbi and Dulago. Any other combination of two Kaulong and Sengseng villages would not have led us past Imlohe’s grave.

- One of the large crude core tools with red petina found in the Silop stream. Bifacially worked, 4 ¾ x 3 inches.

- One of the most typical types of scraper in the collection: one of the trail finds. The striations are natural, 4 x 3 ¼ inches.

- A notched scraper, the one which Iamopli found on the way down to the Silop stream. Finely retouched on both sides. 3 ¾ x 1 ¾ inches.

- Chipped steep scraper, unifacially worked. 4 ½ x 1 ¾. inches.

- Large, bifacially worked axe(?) 5 ½ x 2 ¾ inches.

- Unifacially worked steep-nosed graver(?) 2 ¼ x 1 ¾ inches.