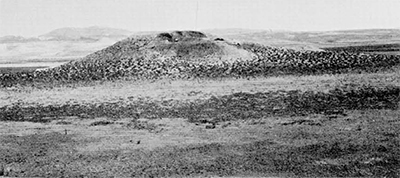

Sometime during the first quarter of the 7th century, invading marauders known to history as the Kimmerians brought to an end the wealthy and influential kingdom of Midas, having left stark testimony of their activities at Gordion, the Phrygian capital. For central Anatolia the event created a political vacuum of uncertain duration, while for Phrygia herself it put an end to foreign contact with the East, hitherto her principal direction of foreign outlook. Although history is silent on the subject, it may have been Gyges, the 7th century founder of the Mermnad dynasty of Lydia, who first took steps to fill the void left by the Kimmerians. At any rate, by the early 6th century the issue of Lydian political influence on the plateau is on somewhat firmer ground, as may be implied by the activities of Alyattes, a later Lydian king, and his seemingly unrestricted passage through Phrygia to confront the Persians on their western frontier. In the time of his successor, Croesus, it is known on the authority of Herodotos (1. 28) that Phrygia was firmly within the Mermnad sway. Physical corroboration of this state of affairs is provided by the artificial hill to the southeast of the main city mound at Gordion. Known as the Kucuk Huyuk or Little Mound, it marks the site of a Lydian fortress, no doubt constructed under Alyattes or Croesus. This outpost of Mermnad interests met its end with the coming of Cyrus and his Persian armies soon after 550 B.C., the very threat which the fortress was probably intended to counter. Phrygia’s second period of foreign rule, thus initiated, was to last until its liberation by Alexander the Great in 333 B.C.

The city of Gordion seems to have prospered under both her foreign masters, although how well the Phrygians themselves fared, and what degree of autonomy they maintained, cannot easily be determined. In any event, the physical aspects of local Phrygian culture, looking back to traditions firmly established in the 8th century and earlier, continued to be strongly manifest in various areas of material production. Together with this persistent local strain, and often affecting it, can be seen much that is exotic, for the Lydian and Persian periods saw quantities of foreign goods coming into the city from a variety of sources.

For Gordion, or any other site, such imported items are of potentially great value, not only for welcome revelations of chronology, but also for the history of ancient trade in general and for the various implications of political, economic and social concerns which they bear. Yet the evidence is delicate by nature, and leaves unsaid much that is to be implied. For all that can really be known about an imported object is that somehow, by some means of transport and under conditions that were in some way favorable, it traveled from its source of manufacture to the place where it was finally deposited as part of the archaeological record. The way need not always have been direct, nor can one assume categorically that all which did arrive at a given site came as a result of pure commercialism. Other modes of travel were undoubtedly in effect, as many, it would seem, as are the modes of human interrelationship.

These and other issues which beset the study of imports may be illustrated in the context of Gordion’s own. Since the corpus exoticum is great, selectivity is essential, sometimes to the point of being ruthless.

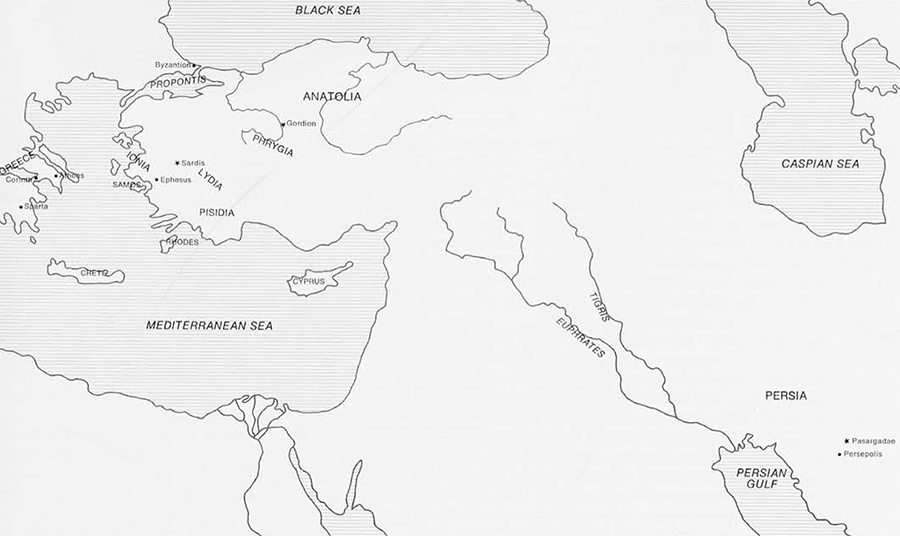

Furthermore, it seems advisable for present purposes to concentrate upon goods whose sources are relatively well assured, since an import loses something of its impact if its origin is unknown. Excluding also what one might call “occasionals,” the principal areas which emerge are three: Greece, Persia and Anatolia.

Greece

In both the Lydian and the Persian periods, the principal index of material communication with the Greek West is pottery. It is, too, the safest index, for although the question of specific origin may arise, especially with East Greek wares, there is seldom any doubt about the essential “Greekness” of a particular piece. However, in dealing with Greek or other imported ceramics, there arises the general issue, usually unanswerable, of whether an amphora, flask, or other closed vessel which could be sealed was the key item of exchange or rather its contents. Cups, plates, bowls and the like obviously do not present this problem.

It is not until the first half of the 6th century, the time of Alyattes and Croesus, that the volume of Greek wares comes to be of considerable proportions. This is, at any rate, the general period which saw the manufacture of the pottery in question. East Greek pottery, which had been known in limited quantity in the 7th century, is now well represented by a variety of types which includes cups, amphoras and plastic vases, some of which may have been produced in Rhodes. From across the Aegean come the products of Corinth, Sparta and Athens, together testifying to a broadening of ceramic horizons in relation to what is known from the preceding century.

From the first of these Mainland centers come vessels of primarily Middle and Late Corinthian style. Aryballoi and alabastra appear to have been most popular, and perhaps brought perfume, but skyphoi and kraters, neither likely types for the transport of any commodity, are also in evidence. Gustav and Alfred Körte, who excavated at Gordion in 1900, found six Corinthian vessels, aryballoi and an alabastron, in their Tumulus I; these in fact outnumbered the local wares. Lakonian is the least frequent of the Mainland wares. What is known consists largely if not wholly of cups and belongs primarily to the second quarter of the century. Attic Black Figure pottery is of a similar range. Here too, cups of varying types seem to outweigh other shapes in frequency. Known since 1900 are the two “Gordion Cups” from the Körte Tumulus V, one by the renowned pair of Kleitias (the painter) and Ergotimos (the potter), the other very close in style and perhaps also by Kleitias.

The University Museum excavations have added much to the Attic corpus of this period, including several specimens which are of value for chronological purposes. One may cite here an amphora reported by G. Roger Edwards in the American Journal of Archaeology 63 (1959) 264-65: coming from beneath the floor of a building belonging to 6th century Gordion, the vessel provides important dating evidence for the rebuilding of the city, an enterprise which one suspects is somehow to be associated with the Lydian presence. Conversely, Attic pottery from the debris of the Kucuk Huyuk fortress may prove to benefit the Athenian chronology from its association with a closely datable historical event.

How much of this Greek material actually came to Gordion during the Lydian period, that is to say before about 547 and the coming of the Persians, is a vital issue if one seeks to correlate patterns of foreign contact with the historical dimension. The question is particularly cogent in the case of several vessels whose production dates hover around the mid-century, for it could be argued that they came to Gordian in the years immediately after the Persian conquest rather than shortly before; in other words, that their importation occurred within a totally different political context. Although the physical evidence itself is largely equivocal, there are certain factors which tend to favor a pre-Persian date of entry for at least many of the Greek wares in question, especially those of the Mainland. The imports from the Kucuk Huyük mentioned above clearly indicate that at least some of the Attic vessels arrived during the Lydian period, perhaps only months or a few years before the conquest. Moreover, it is perhaps too much by way of coincidence that the sources of the Mainland pottery compare very favor ably with what is known of Lydian foreign connections of the time, as though the vessels are a remote reflection of Mermnad politics and diplomacy. Thus Herodotos’ account of the Corcyrean boys sent by Periander to Alyattes definitely indicates some kind of Corinthian link, even if the youngsters never arrived in Sardis (Herodotos 3. 48); while Croesus’ treaty with Sparta is a firm statement of Lakonian relations in the years immediately preceding the fall of Lydia (Herodotos 1. 70). Straightforward Athenian connections are less easy to come by, but may perhaps be implied by stories involving Croesus with Alcmeon (Herodotos 6,125) and Solon (idem 1. 28). Furthermore, it might be remembered that this was a time when a painter called Lydos “the Lydian” worked in Athens and when Athenian boys were being named Croesus. The conquest of Cyrus would have disrupted these Lydian connections with the Mainland; to what extent it affected as well the flow of goods which crossed the Aegean to Asia Minor and the hinterland remains to be ascertained from the ceramic records of Sardis, Gordion and other Anatolian centers.

In no case are the quantities of Greek pottery overwhelming for this period. Even without a thorough statistical study, it is obvious that the overall proportion is very low in relation to local wares or to Lydian. This in itself vitiates any idea of consumption by the masses and points instead to a luxury traffic which was probably enjoyed primarily by resident Lydians and perhaps some Phrygians as well. This impression is to some extent supported by the fact that a fair number of the Greek vessels come either from the Lydian Kücuk Hüyük or from costly tumuli, whereas the simple graves of the rank-and-file so far excavated contain no Greek pottery. Under what circumstances the goods came to Gordion is ambiguous—commercial enterprise promoted perhaps by Lydian merchants? Gift exchange between officials at Sardis and Gordion? Personal property being brought by a Lydian when he took up a new post? At any rate, one suspects that most of the Greek wares at Gordion which arrived came by way of Lydia, that their very importation is ultimately a consequence of the Lydian presence in Phrygia, and that what Gordion received was essentially no more than what the Lydians of Sardis had access to, especially from the Mainland. The testing of these various impressions must await the publication of Sardis’ own Greek pottery.

The Persian conquest, as intimated above, may have brought about a temporary decline in Greek imports, although the matter awaits fuller analysis of the material. East Greek pottery of the last quarter of the 6th century indicates that if there was a lapse from the west coast it was of no great duration, while by the end of the century Attic imports are once more in evidence. They remain pre-eminent well into the 4th century, probably less because of any political considerations than for the Persians’ well attested fondness for the products of Athenian potters. Since the publication of the Greek pottery from Gordion by Keith De Vries will include a full account of the Attic of this period, only a few remarks germane to the issue of trade need to be made here. The incidence of late Black Figure and Red Figure in relation to local wares indicates a luxury category. Furthermore, there seems little doubt that the traffic was a purely commercial one, although a pot may well have passed through many hands before it reached its final owner at Gordion. The mechanics of the trade are all but unknown: Ionia seems the most direct route, but the Propontis and Byzantion may have played roles as well. At Gordion, the commercial aspect is reflected by such shapes as lekythoi and rhyta; these found particular favor within the Persian Empire as a whole, and it seems likely that many were produced by enterprising Athenian potters with the Persian market in mind. One rhyton, thought by Ellen Kohler to be in the Manner of the Sotades Painter, is particularly interesting in this regard, for the artist and those close to him are known to have made conscientious efforts to appeal to the Persian demand in both shapes and subject matter. Whether Phrygians enjoyed any share of this trade is uncertain. If possession was not theirs, they were at least prone to occasional imitation. A local black polished bowl with a tondo of pattern-burnished decoration seems a clever attempt to emulate fine Attic black glazed ware with its stamped and rouletted designs.

After Alexander, what had been a luxury trade in Greek pottery became a commercial enterprise of vaster proportions. Imitation likewise increased, to the extent that the ceramic contents of a 3rd century house may closely resemble those of a Greek kitchen. The essential difference between the two periods is one of Greek influence from afar as opposed to Greek presence.

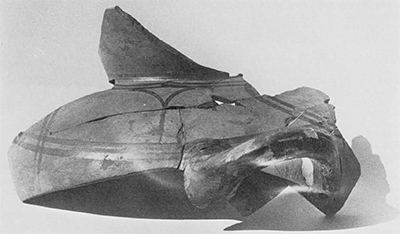

While pottery remains the principal gauge of material contact between Gordion and the Greek world, there are other kinds of artifacts—for instance, a tripod found in a cache of bronzes deposited in a 6th century tumulus. Although fragmentary, there is enough to show that it was of Greek type and no doubt Greek manufacture. The legs, terminating in solid cast, claw-shaped feet, are each of two interlocking pieces, the outer hammered together with a rectangular plate which was in turn affixed by rivets to the shallow body. Additional plates must have been for the attachment of the high rings characteristic of Greek tripods; a piece of one such ring is in fact preserved although not shown in Fig. 6. The basic type may be seen in Karl Schefold’s Myth and Legend in Early Greek Art, pl. 51, bottom. It might be noted that the type shown here and elsewhere in Greek vase painting differs from the Gordion example in having a distinctly incurved rim.

The date of the tripod is problematical since so little is known about actual specimens in the Archaic period. Accompanying material seems no earlier than the middle decades of the 6th century, yet the sorts of items contained in the groupare such that they could represent a fairly wide range of production dates. Thus, whether the tripod came to Gordion during Lydian or Persian times is likewise at issue, as is also the Greek center which produced it. How such an item came to Gordion is equally ambiguous and open to much speculation. The somewhat sumptuous nature of the stand seems less suggestive of commercialism than of some other mode of travel. Much hinges on the identity of the intended occupant of the tomb, whose mortal remains are as yet undiscovered. If Lydian or Persian, or even an important Phrygian sympathizer, it is conceivable that he was included in the distribution of gifts or tribute from East Greek cities, yet the possibility is only one of many.

In the same category of non-ceramic goods may be placed a red scaraboid gem depicting a grazing stag. Following in the tradition of the master lapidary Dexamenos, the seal portrays the type of subject that a Greek gem cutter of the later 5th century would perhaps have produced with Persian tastes in mind.

Persia

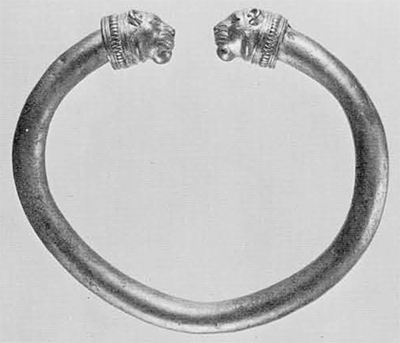

Aside from a few cylinder seals of Achaemenid type, discussed by Rodney Young in “Progress at Gordion, 1951-1952” in vol. 17, no. 4 of the University Museum Bulletin and in “The 1963 Campaign at Gordion” in the American Journal of Archaeology vol. 68, relatively few items of purely Persian origin are known at Gordion. A noteworthy exception, unless its style is deceptive, is a handsome gold bracelet with lion heads from a wealthy tomb of the latter half of the 6th century. This is discussed by K. R. Maxwell-Hyslop in Western Asiatic Jewellery. Discovered as part of an impressive array of gold jewelry, of which certain other items may also be Persian, the piece suggests that at least some Achaemenid luxury goods were traveling west during the first generation or so of Persian rule. The circumstances which brought the bracelet to Gordion are again ambiguous, as is the nationality of its final owner, the cremated occupant of the tomb. It may be noted that a pair of very similar bracelets is worn by the dignitary shown in a roughly contemporary painted tomb near Elmali in Lycia: see Machteld Mellink, “Mural Paintings in Lycian Tombs,” The Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Classical Archaeology (Ankara 1978) pl. 252.

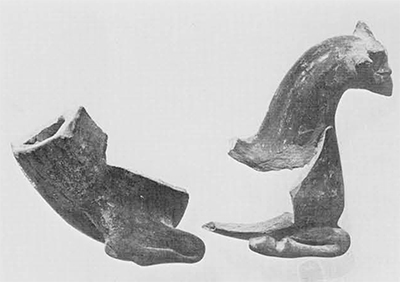

As a rule, one is forced to infer the presence of Achaemenid imports from local ceramic imitations. Various sorts of copies are known or suspected, no small number of which are connected with drinking. Such is true of a series of ceramic rhyta which imitate a famous Achaemenid design known primarily in gold and silver. For the rhyton type, one should compare No. 155 in Oscar White Muscarella (Ed.) Ancient Art: The Norbert Schimmel Collection; No. 162 is a later ceramic version of the type from Anatolia. Another instance of local imitation of an Achaemenid type is provided by Rodney Young in “The 1961 Campaign at Gordion,” in American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 66, pl. 41, figs. la and lb.

Produced rather widely in Anatolia in Persian times and later, these copies imply local acceptance not only of a shape but also of a particular aspect of Persian table etiquette wherein wine, allowed to flow from the short spout at the base into a phiale or other such drinking vessel, was aerated. The procedure involved, adopted by Greeks as well, is illustrated by Noble in The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery, page 152, Fig. 139.

Anatolia

For Anatolian connections pottery is once again of vital significance; but since so little is known about regional production during the 6th and 5th centuries, the matter of provenience becomes a major issue. For the time being, one has to rely to a great extent upon the somewhat questionable procedure of isolating that which does not appear to be local, and, at the same time, that which is not decidedly Greek or of a similarly well defined group.

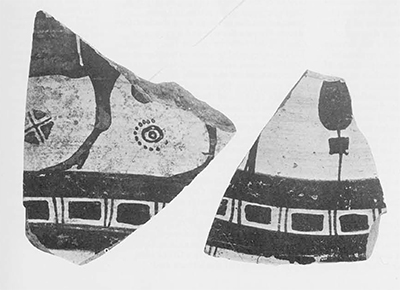

Aside from Lydian (discussed below), there are only a very few categories of Anatolian wares which are not totally enigmatic. One of these is generally referred to as Southwest Anatolian Black-on-Red Ware, a name which seems to be faithful to origins since the greatest concentrations are to be seen in and around Pisidia. It seems, except for Lydian, to have been the most widely traveled of Anatolian wares, known as far afield as Ephesus on the west coast. The several varieties attested probably reflect both geographical and chronological factors, but just as it is a class that is often cited in reports, it is also insufficiently studied as a group.

At Gordion the most frequently occurring type is also the simplest, consisting primarily of small jars and “feeders” embellished with a monotonous series of bars, cursory meandroids and groups of thin lines, sometimes enclosed by heavier lines. An interesting sociological note is that many come from simple graves, the same context in which the excavated examples of the Southwest are found. The chronology, especially that of the simple small pots, is a problem. Strati-graphical evidence from Ephesus indicates that at least some varieties were current in the first half of the 6th century. Certain types at Gordion occur in late 5th century contexts, but these same loci are notorious for their residual material.

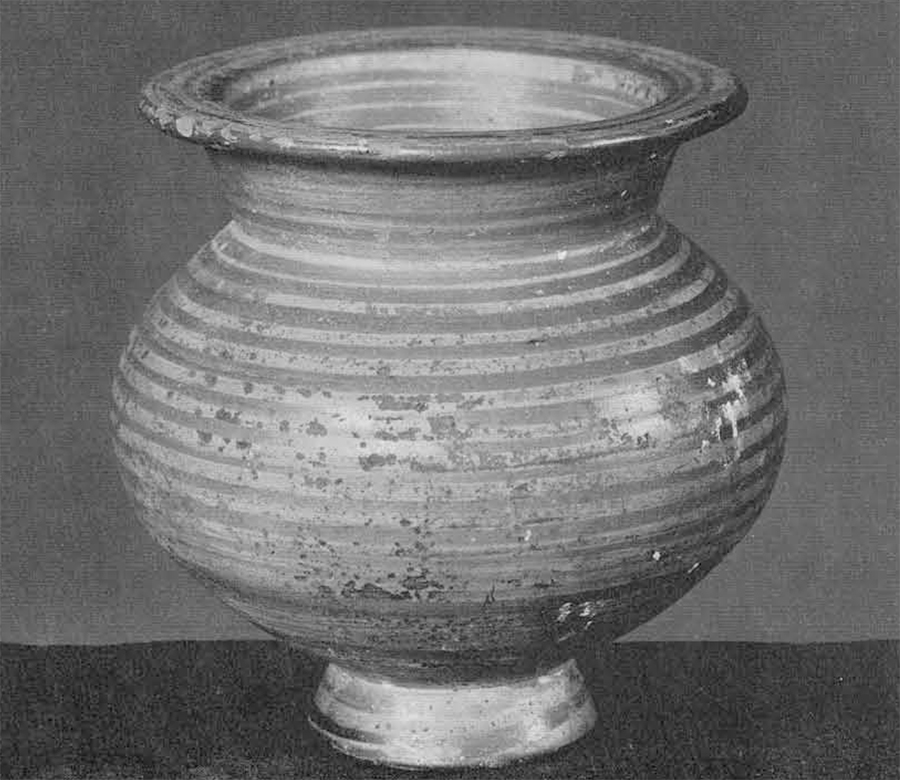

Lydian pottery provides by far the firmest ground for assessing intra-Anatolian connections, thanks to the Harvard-Cornell excavations at Sardis and to the obliging idiosyncracies of Lydian potters. In the 6th century, Lydian is second only to Phrygian in frequency at Gordion, this due less to its popularity among locals than to the Lydian presence up until the time of the Persian conquest.

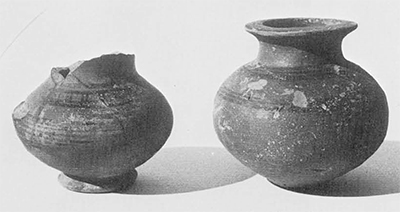

The debris of the Kucuk Huyuk fortress produced great quantities, as did an adjacent settlement, so much so in fact as to suggest that the whole area was a Lydian quarter whose residents in many cases preferred their own country’s wares and products to those of the locals. The shape most characteristic of Lydian production is the “lydion,” of which the fortress produced numerous examples. Thought to be the container for a type of salve or thick unguent, the lydion is also a common item in graves, both humble and elegant, and in the city proper.

Of Lydian techniques, that which is most distinctive and diagnostic is marbling, whereby the surface takes on a richly textured and polychromatic appearance. Essentially a technological development of the 6th century, marbled wares appear to occur at Gordion with considerably less frequency than other Lydian types, perhaps the mark of an expensive product. Other technological features commonly associated with Lydian, but which may prove to be of wider usage, include the use of extremely micaceous clays, as are still to be seen in abundance in the pottery of modern Lydia, and an iridescent, often streakily applied glaze of the same basic type that was employed for marbling. Many skyphoi and lekythoi found at Gordion, from the Kuçuk Huyuk and elsewhere, employ these techniques, as do a few larger vessels which imitate East Greek types.

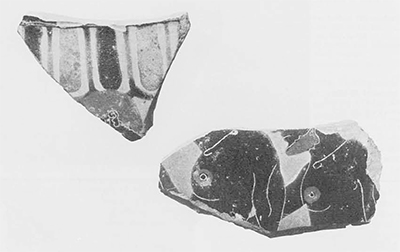

Several other categories of ceramic imports are suspected to be of Lydian origin, although they are without the telltale signs just discussed. Crawford Greenewalt, Jr.’s research has been particularly instrumental in expanding the horizons of Lydian pottery. For example, a couple of Gordion sherds may now be identified as “Early Fikellura,” which he thinks to be a Lydian imitation of the later Wild Goat Style of East Greece and to date between 625 and 575; see California Studies in Classical Antiquity 4 (1971) 153-180.

These several varieties alone represent an enormous quantity of vessels, and at the same time what must have been a substantial outlet for both Lydian potters and the manufacturers whose goods probably traveled in the lydions and certain other closed shapes. It seems reasonable to assume that many Phrygians helped to bolster the market. They at any rate imitated certain Lydian forms in their local wares. The Persian conquest seems not to have dampened the trade, for the same tumulus that produced the Achaemenid gold bracelet with lion heads contained no fewer than ten Lydian vessels, mostly lydions, of its total fourteen. The chronology of Lydian wares at Gordion, and their relative abundance in given periods, await careful study of the stratified contexts. Short of this, the immediate impression is one of a trade of considerable duration, certainly spanning the 6th century and perhaps sustaining itself into the 5th as well.

Aside from a hoard of Lydian electrum coins, minted no doubt in Sardis sometime before the Persian conquest, the attempt to isolate non-ceramic categories of Lydian materials encounters varying degrees of success. Certain seal stones of the Persian period, particularly those of a pyramidal type, may well prove to be the products of Lydian lapidaries; the pyramidals at least belong to a family which includes several examples bearing Lydian inscriptions (see John Boardman, “Pyramidal Stamps in the Persian Empire,” Iron 8 [1970] 19-45).

Less firm ground is provided by other kinds of goods, for by the 6th century distinctions among Greek, Lydian and certain other brands of Anatolian become blurred, owing to the fact that Greek influence had progressed beyond the stages of producing merely quaint barbarisms to a very deft emulation of Greek style. This seems especially the case with minor arts employing primarily floral and floral-related motifs in the Greek vein. The architectural terracottas of Sardis, for example, clearly illustrate that such designs as lotuspalmette chains and egg-and-dart, although sometimes used in non-Greek ways, were in themselves as integrated and comfortable a part of the Lydian artistic vocabulary as of the Greek. The possibility that Greek artisans were active in Lydia complicates the issue, as does the fact that also in Phrygia the use and handling of Greek floral patterns can be fairly adept. This is witnessed to some extent by Gordion’s own architectural terracottas, although some of the molds may prove to have come from Lydia, and by such floral carvings as those of the so-called Unfinished Monument at Midas City.

In other words, one is confronted with a rather widely spread Greco-Anatolian koine which will often render the isolation of sources—Greek, Lydian, Phrygian or other Anatolian—difficult if not occasionally impossible.

Many items at Gordion may be used to illustrate the problem. One is a small ivory disc carefully incised with a circular chain of lotuses alternating with double tiers of fan-like flowers. The issue of origin rests largely upon one’s impressions of what may or may not be admissable as Greek. The grafting of species is a Greek idea, while the forms of the lotuses and connecting stems would be very much at home in an East Greek setting. On the other hand, the peculiar fan-shaped flowers might lead one to favor a Lydian, or general West Anatolian, source if one prefers to see in them the kind of substitution for a more normal Greek palmette which only a barbarian could conceive. Other articles do not yield such possibly intrusive elements but instead adhere closely to Greek concepts of form and design, Whether one is willing to concede that an ambiguity of origin exists depends largely upon one’s relative degree of faith in the artistic abilities of non-Greek peoples.

The ultimate factors which have allowed Gordion to display so much in the way of exotic materials are at once geographical and political. Since the city was well positioned on principal Anatolian highways, the means of communication were always there; yet the avenues which were to be emphasized and most heavily traveled were determined primarily by historical and political conditions. Most of the goods which found their way to Gordion from the 6th through the 4th centuries came as a consequence of political networks established by Lydians and Persians, over which the Phrygians themselves doubtlessly had little or no control. The result was that the ancient capital found itself in cultural agreements with prevailing empires. Both Lydian and Persian have placed indelible stamps upon the city, impressions which reflect not only their own respective civilizations but also their various interests in the world of Greece.