Eskimos and North American Indians first came to the attention of Europeans ca. A.D. 1000, when the Norse journeyed to the coasts of Greenland and North America. The Norse called the strangers they encountered on the shores “skraelings,” and noted that when skraelings were wounded they turned white but did not bleed (Gad 1971:88).

Beginning in the mid-16th century, somewhat more reliable descriptions of Eskimos appeared in records written by Basque and Dutch whalers, and European explorers such as Martin Frobisher. Observations of the lifeways of Eskimos living in Siberia, northern North America, and Greenland have flowed from the pens of whalers, fishermen, traders, trappers, explorers, missionaries, scientists, and Eskimos since that time.

The public has a romantic and not entirely accurate image of Eskimos, despite over 400 years of written documentation. Most people imagine that all Eskimos live in a similar fashion and speak the same language. Since the Arctic is geographically remote to most people, the public assumes that Eskimos are and always have been isolated from contact with other groups. According to the general stereotype, Eskimos occupy a cold, flat, snow-covered world, marked only by periods of continual daylight and endless night. They live in houses fashioned out of blocks of snow, survive on a diet of whale and seal meat (eaten raw), wear clothes of animal skin which has been chewed by women, and own only what they can carry on their backs or transport on their dog-drawn sleds. Instinctively Eskimos know where to find game (which they secure with intricate technology), thus fending off the ever-present threat of starvation.

The real Eskimo world is more varied and complex. There are sod house villages occupied by 300 people; largely sedentary fishing communities; bone slat armor that is used in warfare; an origin myth in which man falls from a pea pod created by Raven; large wooden masks with intricate appendages and a complex iconography; a 2000-year-old artistic tradition; plant harvests; and trade fairs where Asian metal, Alaskan jade, Canadian soapstone, and Greenlandic meteoritic iron are exchanged. These are not images or activities commonly associated with Eskimos, but do include some important aspects of Eskimo culture currently being studied by Arctic anthropologists.

Within the last decade Arctic research has taken giant strides due to an increase in the numbers of scholars and projects. In archaeology alone, half of the literature currently available was written in the last decade (Maxwell 1980:163). Researchers are beginning to understand the ecological complexity of the Arctic and the distinct adaptation strategies adopted by Eskimo groups living during certain time periods in various parts of the north. A growing number of studies are concerned with the nature and implications of Eskimo-European contacts as well. Ethnographers and archaeologists are re-evaluating assumptions about the structure of Eskimo political and economic organization, while there is an increasing number of studies dealing with social and religious aspects of Eskimo life. Finally, a number of scholars are studying the impact of modernization and development on northern communities. However, despite a long history of archaeological work in which culture history problems have dominated the literature, the Eskimo prehistoric cultural chronology remains frustratingly unclear (Giddings 1967; Dumond 1977).

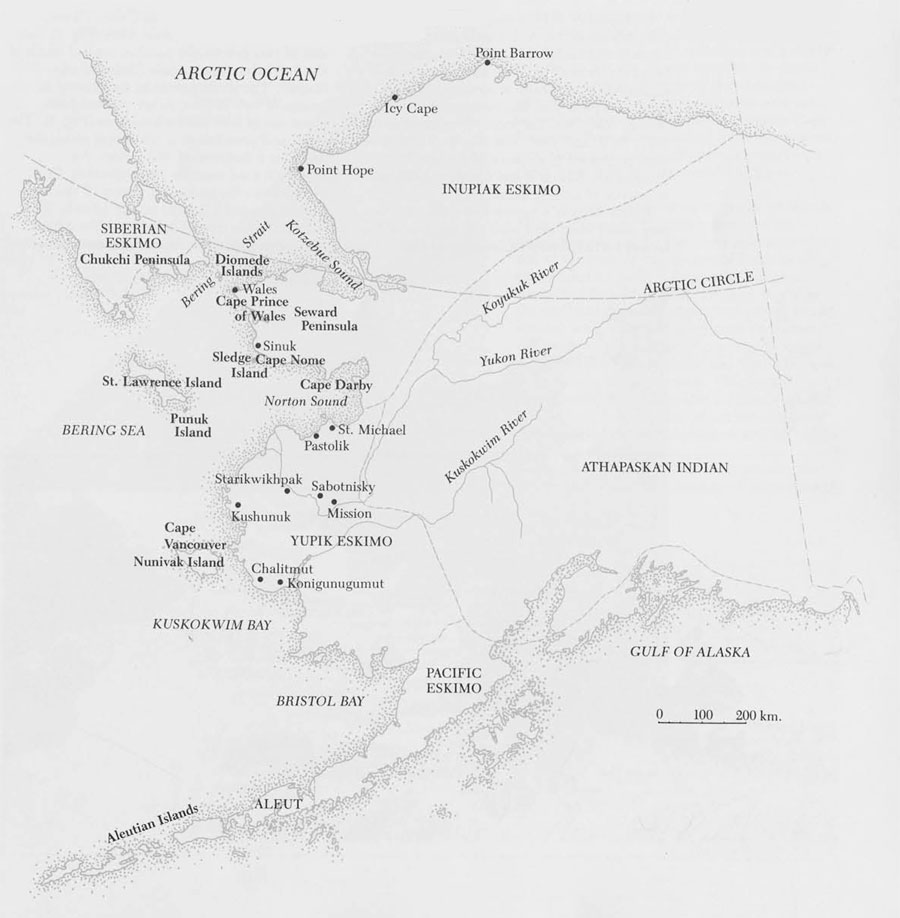

The papers in this issue of Expedition are a sample of some of the ongoing research involving Arctic scholars. Mikhail A. Chlenov and Igor I. Krupnik report on a recently discovered whaling ceremonial complex on the Chukchi Peninsula. That a number of large sites with obvious architectural features are only now being found is not surprising to Arctic archaeologists, who have yet to survey great expanses of the north. How these sites fit into the culture history of Siberia and their relationship to the north Alaskan whaling complex are interesting questions for which there are no immediate answers.

Susan A. Kaplan, Richard H. Jordan, and Glenn W. Sheehan describe a whaling outfit from Sledge Island, north Alaska. This unique collection was brought to The University Museum in the early 20th century and was recently rediscovered in the Museum’s American Collections storage. The significance of the outfit is explained through a discussion of leadership in 19th century north Alaskan whaling communities and the role of hunting magic in Inupiak-speaking Eskimos’ lives.

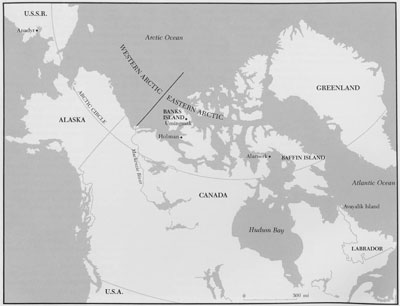

William W. Fitzhugh addresses the question of the prehistoric origins of the Yupik-speaking Bering Sea Eskimos. Using archaeological evidence and 19th century ethnographic collections, he suggests that the intricate technology and complex symbolism of the Bering Sea Eskimos’ sea mammal hunting complex have their roots in a 2000-year-old tradition, Bernadette Driscoll focuses on the contact period among eastern Canadian Eskimos (referred to as Inuit in Canada). She examines how 19th century Inuit women extended the symbolism represented in skin tattoos and traditional garments by decorating parkas with glass beads brought by foreign whalers.

We are pleased to present papers on the research efforts of Soviet, American, and Canadian scholars. In addition to the authors, I would like to thank Henry Michael who first approached Drs. Krupnik and Chlenov about a possible contribution, translated their manuscript from Russian to English, and has been an endless and patient source of information.

Fred Schoch, Staff Photographer, had the difficult task of photographing the beaded parka appearing on the cover. Robert H. Dyson, Jr., and Gregory L. Possehl provided some of the funding for photography. Irene Romano (Acting Registrar) and her staff, Caroline Dosker and Eleanor King (Archives), and Pamela Hearne (Keeper of American Collections) have extended various forms of support. The authors are grateful to them all.