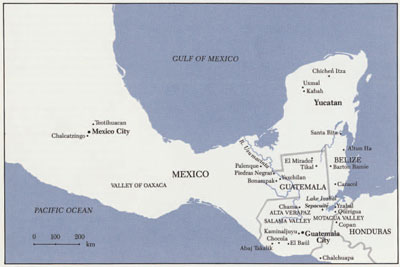

The civilization created by the ancient Maya is recognized throughout the world as one of the most notable achievements of pre-industrial human society. But while many ancient civilizations in the Old World have long been known arid investigated, knowledge of the ancient Maya is a relatively recent phenomenon. The study of this brilliant civilization, centered in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula and northern Central America, spans a little more than a century (Fig. 1).

The recognition and understanding of Maya civilization derives from research conducted over this period by scholars representing a broad spectrum of backgrounds, interests, and expertise. Today we usually define most of these concerns as distinct academic disciplines. My own specialization, archaeology, is only one of several scholarly approaches, such as art history, ethnohistory, epigraphy, and linguistics, that are vital to Maya studies. Quite obviously, each of these fields has made important contributions to our knowledge of the ancient Maya. But the greatest successes and the best prospects for future breakthroughs —for there is much still to be learned—will surely derive from combining the unique strengths of each approach in an interdisciplinary research strategy.

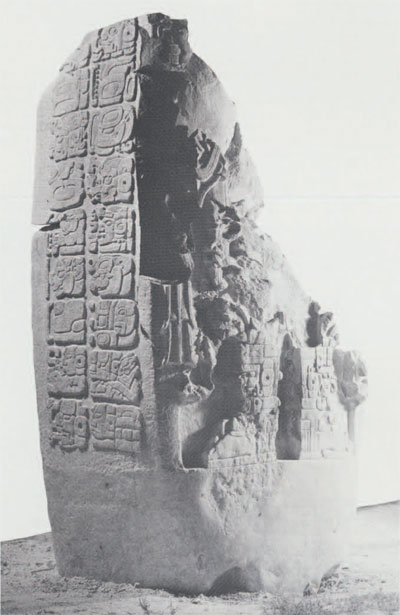

Not the least of the achievements of the ancient Maya was their complex system of writing. The recent progress that has been made in deciphering this script stands as one of the best examples of the advantages of interdisciplinary scholarship (Fig. 2). As a result of the gains made in this decipherment. the study of ancient \lava civilization has crossed the threshold from Prehistory to History. The significance of this development can hardly in overemphasized. Most of the human past is prehistoric, encompassing the gradual emergence of our species and the incredibly long and gradual development of human culture. Our cultural evolution spans several million years and is highlighted by technological achievements such as control of fire, the making of increasingly sophisticated tools, and the development of agriculture. But our knowledge of all these past developments is indirect, derived from archaeological inferences based on the few material remains that have survived and have been recovered. With the comparatively recent invention of writing, however, direct communication from the past is possible, provided the ancient messages can be deciphered. And this is exactly what is nn happening in Maya studies—we are able to read the writings from a past civilization that was, until now, essentially mute. The study of the ancient Maya is undergoing the same profound change that occurred in Egyptian and Mesopotamian studies with the decipherments hieroglyphic and cuneiform scripts in the 19th century. History is being added to what has already been gleaned from the archaeological data.

Complementing the breakthroughs in decipherment, Maya archaeologists have revolutionized our understanding of ancient Maya society. Generally speaking, this was due to the application of a broader research strategy, one usually labeled “settlement archaeology” (Fig. 3). The result has been a more holistic view of the ancient Maya. Instead of concentrating on the architectural core of a site, the entire site—from core to periphery—is subjected to equal examination. And instead of concentrating on only the larger sites, a full range of sites—from biggest to smallest—is investigated. By systematically searching for and excavating a broad spectrum of remains of past society, our entire perception of Maya civilization has been altered.

The first application of this strategy in the Maya area was directed by Gordon R. Willey, a pioneer in settlement archaeology, at about the same time as the initial breakthroughs were being made in decipherment. His work was at Barton Ramie, a series of rural settlements in the Belize river valley. Soon thereafter, The University Museum’s Tikal Project, the largest archaeological effort ever conducted in the Maya area, adopted many of the objectives of settlement research. Since that time almost all Maya archaeological research has utilized this broader-based research strategy to some degree. The most recent Maya investigation sponsored by The University Museum, the Quirigua Project, comprised two programs, one for the site core and the other for the site periphery, in order to produce a complete and balanced investigation of the entire site. Beyond this, a Lower Motagua Valley Program sought information from a vast surrounding region during the period of Quirigua’s occupation.

These recent archaeological investigations have completely overturned the old view of Maya civilization. For the first time, a great deal of information about the non-elite portions of society has become available. Populations at Maya centers once assumed to have been small and scattered proved to be large and relatively concentrated. A rather homogeneous agricultural peasantry has turned out to have been internally differentiated by wealth, occupational, and status distinctions. The larger Maya sites once considered near-vacant ceremonial centers have been revealed as formerly populous cities. The ruling elites at these cities, far from being peaceful priests interested only in esoteric concerns, are now known to have waged war, formed alliances, performed rituals and sacrifices—in short, to have participated in a Full range of activities. from the petty to the profound. similar to those documented from other early civilizations. And the hinterlands of the Maya area have proved to be filled with the remains of a complex and sophisticated agricultural system that included raised (drained) and terraced fields. Overall, then, it now is obvious that Maya civilization was larger, more complex. and less exotic than the traditional interpretation allowed.

What Next?

Although Maya scholars have provided a new perspective on Maya civilization, some may consider the resulting picture Iess romantic than the traditional reconstruction—for now much of the former unique quality and ‘mystery’ of the ancient Maya has been removed. But the lovers of mysteries need not despair, for the Maya still offer unanswered questions aplenty. While the collapse of Classic Maya civilization can no longer he viewed as a monolithic event, it remains largely unexplained, especially since we now realize this was part of a continuous process—although many sites were abandoned at the close of the Classic era, the careers of other cities ended well before or after this period. And recent research in both the lowlands and highlands into the preceding Preclassic era, the period when Maya civilization first emerged and crystalized, has raised as many questions as it has provided answers.

Investigations in the highlands and along the Pacific coast have revealed complex and precocious sites extending as far back as the Olmec horizon (Early and Middle Preclassic). During the Late and Terminal Preclassic this southern area seems to have given rise to traditions of sculpture and writing immediately ancestral to those of the Classic period lowlands. And recent research in the lowlands has produced the most dramatic evidence of Preclassic cultural development at the site of El Mirador. This truly mammoth site, served by a series of radiating causeways, contains constructions on a scale never again approached in the Maya area, dwarfing the largest buildings of the later Classic era. But the full significance of El Mirador and of the early developments in the southern Maya areas remains to be explained.

As we have seen, Maya studies have undergone a revolution in perceiving the past. But lest we fail to learn from what has happened in the first hundred years of research, we should bear in mind that our successors in the 21st century may well look on our present reconstruction of Maya civilization as woefully incomplete and inaccurate. It is safe to assume that many of the questions that are unanswered today will be successfully tackled by future scholars, provided the archaeological record does not continue to be destroyed at the present pace. So, far from being over, it would appear that the ultimate Maya ballgame has just begun.