The five millennia between approximately 9000 B.C. and 4000 B.C. were vital ones in the history of the Middle East and indeed of all mankind. There is no need here to go into the details of what this critical period involved, for most readers will have some idea of the multifacetted impact of the interrelated changes often called, in shorthand form, the “Neolithic revolution.” At the beginning of this time the ways of life were apparently entirely dependent on hunting, gathering and perhaps fishing; by the end—which I place, rather arbitrarily, at about 4000 B.C.the main emphasis of subsistence was on various forms of food-production and settlement was based on occupation in largely sedentary villages and even substantial towns. Along with these primary shifts went great increases in population size and density, the invention of important elements such as pottery, metallurgy, and complex architectural forms, plus developments in social and political organization, religion and ideology, at which we can do little more than speculate at the moment. By 4000 B.C., after what to a prehistorian accustomed to the leisurely evolution of earlier times seems a cultural explosion, southwestern Asia had quite literally been transformed into something new and unique. A platform had been built for the next leap into the complex world of urban life locally, while through various channels the principles of the new way of life were seeping in all directions to transform to greater or lesser degrees large areas of the Old World.

The role of Iran in this transformation has become clear only in very recent years. I use the word clear in a very relative sense because we are still unable, for lack of enough information, to understand most of what was happening in Iran throughout this period. Nevertheless it is fair to say that the 1960’s saw a very significant advance as far as the Neolithic, particularly its earlier stages, is concerned. Many new sites were discovered, some of the blank areas on the archaeological map were at least given some semblance of occupation and, perhaps most important, the chronology of the Iranian Neolithic was pushed back to reveal a much greater antiquity and a more complex array of developments than had hitherto been suspected. Until around 1960 only about a half dozen Neolithic sites were “known” in the sense that something reasonably detailed had been published about them, and the oldest went back to what we would now consider the middle part of the Neolithic. Today at least two dozen sites are known (excluding caves with temporary or brief encampments and sites that have only been surface collected) and the number increases yearly, though admittedly very few have yet been published in any detail; and a few of these Iranian sites go back to the eighth and possibly even the ninth millennia B.C. and must represent the activities of groups who were involved in the beginnings of the great change.

The reasons for the slow development of interest in the Iranian Neolithic are various. In part it reflects modern political events, including the fact that, unlike Iraq and Syria, Iran was not a mandated country when Western archaeologists were beginning to interest themselves in the earlier phases of Middle Eastern prehistory between the two world wars. Access was difficult and expensive and until the 1930’s virtually no foreign archaeologists other than French ones worked in the country. Equally important, I suspect, in dampening enthusiasm was the prevailing hypothesis that the beginnings of animal and plant domestication and of sedentary life must have taken place in the great river valleys of lowland regions or in well-favored oases. As a largely upland and plateau zone, Iran tended to be ignored by those interested in the earlier stages of agriculture, and what Neolithic was known could be explained in terms of diffusion from other regions. When the war of 1939-45 broke out and imposed a halt of nearly a decade in the research of Western archaeologists, practically all our knowledge of the Iranian Neolithic was derived from the site of Sialk near Kashan on the western edge of the Dasht-i-Kavir desert, excavated by Roman Ghirshman for the French Archaeological Mission from 1933 to 1937. In the basal levels of the North Mound at Sialk were several thick series of deposits, the earliest of which the excavator tentatively interpreted in spite of its well-developed painted pottery as reflecting a transitional phase of adaptation to a new way of life under conditions of increasing aridity; the later levels (Sialk II and III) represented the inevitable complexity of sedentary life and a committal to food-production. This interpretation seemed to be supported by Pumpelly’s old evidence from the site of Anau in Soviet Turkmenia and by the meager evidence from the few other sites in Iran where Neolithic traces had been found in the course of soundings in mounds: Tepe Hissar in northeast Iran, excavated by Erich Schmidt for the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the American Institute for Art and Archaeology in the 1930’s; Chesmeh All near Tehran investigated by Erich Schmidt for the University Museum and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; and by various French archaeologists at such sites as Tepes Jaffarabad, Musiyan, Khazineh, and Ali Kosh (all in Khuzistan) and Tepe Giyan (in Luristan) during the first third of the century.

Today, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that these are all relatively late occurrences, ranging from at the earliest about 5500 B.C. (Sialk I) to the fifth and even fourth millennia—that is, the equivalent of the Hassuna-Samarra Halaf-Ubaid developments in Mesopotamia proper. They tell us very little about the earlier stages when the first Iranian farmers were working out a new set of ground rules for living.

Carleton Coon’s investigations at Belt and Hotu caves on the Caspian foreshore in 1949 and 1951 for the University of Pennsylvania marked a deviation from the traditional approach. He investigated caves rather than mounds and found materials ranging from “Mesolithic” to “Sub-Neolithic” as well as pre-ceramic Neolithic and Early and Late Neolithic with software pottery. He paid special attention to the subsistence patterns of the inhabitants and particularly to the faunal remains. Even more important at the time, he obtained “absolute” dates by using the just-developed radiocarbon method and for awhile had what seemed to be the earliest Neolithic dates in the world. Finally, Coon tossed a new hypothesis into the slowly simmering pot of archaeological thinking by suggesting that perhaps the origins of the Neolithic lay neither in the great river valleys or oases as people such as Gordon Childe and Ghirshman thought, nor in the medium altitude upland zones as another group of prehistorians headed by Robert Braidwood were beginning to think, but rather in an environment such as the lush Caspian foreshore and environs from which it spread eastward and westward. It is still difficult to prove or disprove Coon’s hypothesis since no one has gone back to dig in the Caspian Neolithic sites, but there is a general feeling today that probably the Caspian sites represent occupations by late-lasting hunters and collectors who had adopted various elements of Neolithic life as a result of diffusion from elsewhere in Iran. But in any case in the 1960’s Neolithic research in Iran took a new turn which has led directly to the spurt in accumulation of information I mentioned earlier.

In 1959-60 Robert Braidwood of the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute moved into the Kermanshah Plain of west-central Iran to test further an hypothesis he had already tried out in the Jarmo region of northeastern Iraq. Believing that the origins and earlier stages of animal and plant domestication of southwestern Asia were more likely to be found in the upland zones where the potential domesticates had their natural habitats, and assuming that climatic and environmental changes had played an insignificant role in the transition from hunting-collecting, he surveyed the Kermanshah and Shahabad valleys and excavated a number of cave and open sites ranging from Mousterian to Halafian times. As far as the Neolithic was concerned, the most important sites were Tepes Asiab and Sarab which were partially excavated in early 1960. Although Braidwood’s group did not continue work in Iran after 1960, some of its members did so as individuals. Frank Hole and Kent Flannery began a program of research in Khuzistan which uncovered a long sequence of local Neolithic development; Herbert Wright, Jr. of the University of Minnesota continued his investigations in the climatic background of Neolithic times, especially through the study of pollen sequences from lake-bed cores in the Zagros mountains; while Robert Adams of the Oriental Institute surveyed the Khuzistan region in 1960-61 and located a large number of sites going back to the sixth millennium. At about the same time, in the northwest, Robert Dyson and T. Cuyler Young, Jr. for the University of Pennsylvania Museum had excavated in the mounds of Hajji Firuz and Dalma in Azerbaijan, south of Lake Rezaiyeh, and had uncovered Neolithic settlements going back to around 6000 B.C. A British group under Charles Burney had found at Yanik Tepe near Tabriz evidence of Neolithic occupation belonging to the centuries just before 5000 B.C. In Luristan a Danish expedition excavated the site of Tepe Guran in the Hulilan valley in 1963, with Feder Mortensen investigating the Neolithic deposits. In 1965 two Canadian groups, T. Cuyler Young, Jr. for the Royal Ontario Museum and the writer for the University of Montreal, began investigations at Godin Tepe and Ganj Dareh Tepe respectively in the Gamas-Ab valley of southern Kurdistan. Most recently C. Lamberg-Karlovsky of Harvard University has extended the Neolithic trail eastward by uncovering fifth millennium occupations at the base of Yahya Tepe in Kerman on the southern Plateau.

Some of these sites are still being excavated while at others the work has been (one hopes temporarily) suspended. Only the findings from Tepes Ali Kosh and Sabz, excavated in 1961-63 by Hole and Flannery in the Deh Luran Plain of Khuzistan, have yet been published in any detail. Thus those archaeologists who are involved in making some sense of the Iranian Neolithic still have a long way to go. Some things are gradually coming into better focus, it is true, but others are as puzzling as ever. So this brief article is not intended as an authoritative synthesis of this slice of Iranian prehistory but only as a tour d’horizon to indicate where we stand today in our knowledge (and ignorance) of the Neolithic of Iran.

What the precise origins of the Iranian (or, for that matter, any other Middle Eastern) Neolithic are, we are still a long way from knowing. In the Zagros, at least, the latest hunting-gathering culture seems to have been the Zarzian who lived apparently in caves and rock-shelters, and just possibly were already involved in some kind of plant and animal control by the tenth millennium.

So far, however, there is no clear demonstration in either Iran or Iraq of direct continuity from the Zarzian to the earliest food-producers. In Iraqi Kurdistan the earliest evidence of food-producing seems to come from the Soleckis’ site of Zawi Chemi Shanidar where possibly sheep were being domesticated by the early ninth millennium. Perhaps Braidwood’s site of Karim Shahir represents the same stage in the Iraqi piedmont. In Iran the ninth millennium evidence is still vague but there is some reason to believe that similar developments were taking place in the Zagros area at least. Tepe Asiab near Kermanshah, though it has yielded no radiocarbon determinations, could belong to this period, and recent studies of the animal bones indicate an early stage of goat domestication here. At the base of Ganj Dareh Tepe not far away there is a meter of deposits, apparently without solid architecture, which may go back to the mid-ninth millennium; unfortunately we still do not have conclusive evidence for food-production in this basal level, though further digging may reveal it. The eighth millennium, which up to recently has been something of a blind spot in the prehistory of Iran and Iraq, is well represented in the succeeding levels of Ganj Dareh from about 7500 to 7000 B.C. In these levels preliminary studies by Dr. Dexter Perkins of Columbia University suggest that goats at least were being reared. Up to now the evidence for cereal domestication in this site is more elusive, but the presence of many milling and grinding stones and of large clay containers and bins tempts one to think that some kind of plant foods, whether wild or domesticated, were being prepared and stored. One of the lower levels of Ganj Dareh was partially destroyed in a fire and this accident has revealed two rather surprising aspects of the early Iranian Neolithic. The first is the presence of very sophisticated forms of solid architecture using long plano-convex bricks, several types of walls made of clay and plaster strips and solid mud walls, especially to construct clusters of rectangular rooms and small cubicles. Whatever these structures were meant for they suggest something more than brief or even seasonal occupations. The second is the existence of rather simple but nevertheless definite pottery, perhaps very lightly fired originally, which dates before 7000 B.C. and is the oldest so far known in the Middle East. This pottery takes the form of both small pots and very large jars and trays, with no traces of painting, and some of it may be ancestral to the earliest pottery at Tepe Guran.

Ganj Dareh was abandoned around 7000 B.C. or shortly after, but it is probable that by this time the advantages and disadvantages of the new style of life had caught on in a number of communities in the Zagros. A site very like Ganj Dareh, Tepe Abdul Hosein, was found only last year in Luristan though it has not yet been excavated. Very soon after 7000 B.C., if not by then, there were occupations at the base of Tepe Guran in Luristan, at first apparently by groups of transhumant goatherds in the winter who lived in brush huts and perhaps lacked pottery, later by more sedentary groups in mud- and brick-walled houses. By the end of the seventh millennium there were more specific links with groupings on the Iraqi side of the Zagros, such as those characterized by the site of Jarmo, with well-established villages based on an array of domesticated animals and cereals. In the Iranian Zagros this stage seems to be represented by such sites as Tepe Sarab and the upper levels of Tepe Guran. It is about this time, too, around 6000 B.C., that we find the first traces of occupation by what seem to be food-producers in the Solduz valley of Azerbaijan south of Lake Rezaiyeh, at the site of Hajji Firuz and a few others. On the Iranian plateau, Sialk was first settled about this time or shortly after. Hassuna and Samarra influences from Iraq may have been partly responsible for some of this spread. Probably some changes were also creeping into the lives of the surviving seal and gazelle hunting peoples around the Caspian, though it is hard to be sure what the changes were or to what extent their traditional ways were modified; pottery seems to have reached them by the sixth millennium but we are still uncertain when food-production was adopted. The routes of diffusion across the eastern part of the Iranian plateau are even more vague. Presumably the Jarmolike villages of the Jeitun culture and the vigorous later cultures typified at Anau and Namazga in Soviet Turkmenia were inspired from Iran, as were the food-producing groups of northern Afghanistan of the sixth millennium; but so far eastern Iran is almost completely blank as far as the Neolithic is concerned. What was happening in Khorassan, Seistan, and Baluchistan, the areas through which we suppose some of the Neolithic elements passed eastward into Afghanistan and Pakistan, is still wholly unknown.

Thanks to the work of Hole and Flannery on the Deh Luran Plain, we are much better informed on what was happening in southwestern Iran, in the region of Khuzistan where the Zagros range peters out adjacent to the Mesopotamian Plain. There is no evidence that the earliest Neolithic had its origins here, in a low altitude steppe environment where presumably the necessary domesticates were not at home. But sometime around 7000 B.C. (give or take a few centuries—the radiocarbon dates are “whimsical” for this period) the Bus Mordeh phase at the base of Tepe Ali Kosh shows people building small mud-brick structures, perhaps for winter occupation only, and raising sheep and goats, and some wheat and barley to supplement their hunting and collection of wild plant food. Perhaps they represent transhumant groups of simple farmers without pottery who had moved southward along the Zagros into an unoccupied region and had by now gained sufficient control over their animal and plant resources so that they could maintain a foothold in this marginal habitat. Over the next few thousand years their successors developed a greater commitment to food-production, adopted pottery and simple irrigation, built larger and more permanently occupied villages distributed over a wide area of Khuzistan, and with considerable stimulus from the contemporary peoples of Lower Mesopotamia evolved, in the direction of life in villages and minor towns. By the fourth millennium, a trend toward the abandonment of some villages and a clustering in larger towns is observable, perhaps in part due to excessive soil salinity, but this prelude to Elamite civilization is beyond the scope of this article. Long before this, however, it seems that the Fars region had been settled, perhaps by around 5500 B.C. at Tepe Djari and later at Tal-i-Mushki, Bakun, and Tal-i lblis by groups using plain software pottery.

Presumably the earliest settlement at Tepe Yahya in Kerman represents a further movement eastward. The claim by a German geologist, Huckriede, for an “Upper Mesolithic” at Kuh-banan north of Kerman with possibly the incipient cultivation of local cereals has not been substantiated, and the microlithic industry remains undated.

In the central Zagros the details of the occupation after 6000 B.C. are not too clear. The area was certainly inhabited, as is demonstrated by important sites at Tepe Giyan, Tepe Siabid near Kermanshah, and Godin Tepe (periods VII and VI), but it had apparently lost its former lead in Iranian cultural development. Given the resources available and the technological level, it had probably reached a rather stable equilibrium which it maintained for many thousands of years. On the plateau we have a better picture of the final stages of the Neolithic, at sites like Sialk (period III) and those in Fars and Kerman. Here we can see metallurgy, in the form of smelted copper, growing in importance, towns becoming larger and more complex, trade increasing across wider areas, population growing in size and density, and agriculture becoming more intensive. Where to draw the line to mark the end of the Neolithic is a difficult problem. I have put it at about 4000 B.C. here, thus including much of what is often called the Chalcolithic, because the fourth millennium was a period when, although basically Neolithic peoples undoubtedly continued to colonize many regions either unoccupied or inhabited by surviving hunters and collectors, the Neolithic “revolution” was essentially accomplished. A new set of cultural, social, and technological phenomena was emerging, particularly in southwestern Iran, in large part the result of events originating outside Iran itself. These outside features in combination with the indigeneous ones led to the distinctive Iranian Bronze Age cultures of the fourth and third millennia B.C.

On the basis of this imperfect array of information, what kind of picture emerges about the Iranian Neolithic? With all the hesitancy of the prehistorian still groping in near-darkness I propose the following reconstruction. From a center in the Zagros range and its flanking hills in Iran and Iraq, groups who were essentially intensive collectors and hunters began by the tenth millennium to modify their cave-dwelling, mobile way of life, perhaps in part under the impetus of the somewhat warmer and less arid climatic conditions then existing. Some of these groups may have been living in relatively sedentary villages, though we have as yet no good example from Iran of permanent-structured settlements dependent on hunting and collecting, such as apparently existed at this time in Syria and Israel. In the ninth millennium the trend towards greater sedentariness was probably speeded up with more regular control over certain animals and cereals in the form of simple cultivation in clearings and seasonal transhumancy. In the next few thousand years a complex set of factors, probably including human population pressure on available land, led both to an intensification of the agricultural system and to the expansion of some groups into regions hitherto uninviting for food-producers. Agriculturalists now for the first time spread into parts of Iran outside the original center of domestication, to Khuzistan, the Lake Rezaiyeh basin, and the central and southern plateau. In this latter region there may have been fairly early an emphasis on migratory stockbreeding, on trade and, by the late fifth millennium, a simple metallurgical industry.

This reconstruction is of course not a very original one and in many ways it duplicates what has been suggested for other parts of the Middle East at this time. The contribution of the work of recent years by archaeologists of many nationalities has been to show that Iran was indeed deeply involved in the development of the Neolithic of southwestern Asia, and, in such things as the invention of pottery and the elaboration of various forms of brick and mud architecture, may even have been in the van. Even after 5000 B.C., when the lowland zones of Mesopotamia were taking the lead in cultural developments, it is likely that the highland zone of Iran had far more influence on the events of neighboring regions than is usually thought.

A listing of the problems to be resolved and the gaps to be filled before we can say whether this picture is a moderately faithful reflection of prehistoric reality would be far too long for this short survey. Perhaps the most important general task is to find out more about the earlier stages of the Neolithic outside the Zagros; we are, comparatively speaking, somewhat top-heavy in data from this zone and it perhaps distorts our interpretations. This is a particularly pressing problem for central and eastern Iran, while the Caspian area poses a set of fascinating problems of its own. Was Coon justified in claiming food-production here as early as about 6000 B.C.? Was the Caspian foreshore really as important a “breeding ground” for the diffusion of the Neolithic eastward to central Asia and westward to Europe as he also suggested? Even within the fairly well explored Zagros some valleys have yielded no earlier phases of the Neolithic, for example the Rumishgan and Tarhan valleys; were topographical or other environmental factors responsible or have the sites not yet been identified? Again, how late did full-time food-collectors and hunters survive in each region, and how did they influence the local Neolithic patterns?

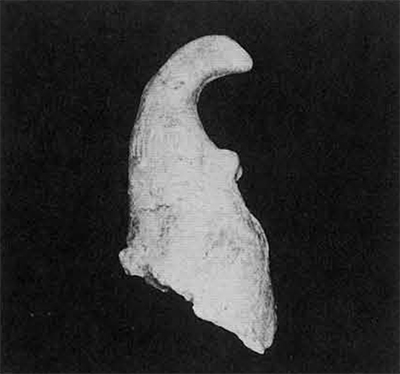

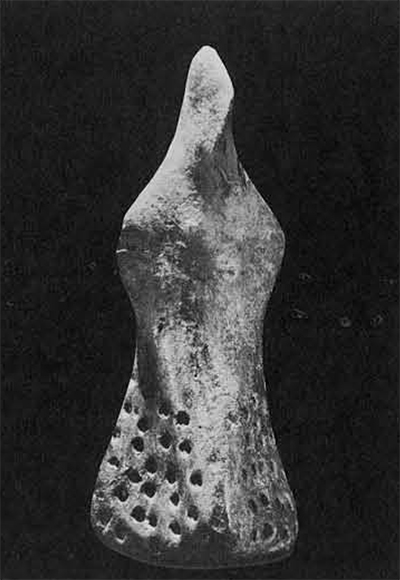

University Museum Object Number: 69-12-18

We must also find out more about the climatic, environmental, and economic background of the Neolithic events. What kinds of agriculture were practised in each region in terms of crops, fallow periods, types of land use, the differential importance of plants versus animals? What part did seasonality of occupation and activity play in creating the variability observable in the earlier sites? How far back can we trace a pattern of genuine pastoral nomadism in Iran? What were the climates and environments at the beginning of and during the course of the Neolithic in the various zones of Iran, and how did these influence the directions of development? What was the role of trade and trading networks in the initial dispersal of ideas and elements (e.g., by the trade in obsidian from Anatolia after about 7000 B.C.), and later in the founding of specialized villages for production and export of certain resources? To what extent can we talk about fully indigenous developments in Iran and how much importance should we allow for influences from outside, particularly from Mesopotamia in the later stages? What is the origin of the Susiana cultural pattern, including the abundant painted and decorated pottery and irrigation-aided agriculture, which appeared in Khuzestan about 5500 B.C.—was it in the preceding local Neolithic phases, or from outside, or both? How real, in view of the apparently accidentally preserved pottery at Ganj Dareh Tepe, is the concept of an aceramic or pre-pottery Neolithic—and therefore how much longer can we claim that Iran has the oldest pottery west of Japan? Is this eighth millennium pottery the origin of the later softwares of much of Iran and Iraq? What physical types were responsible for the various Neolithic manifestations and how much continuity was there biologically with preceding and following periods?

Like most of their colleagues elsewhere, Neolithic archaeologists in Iran are hampered by the fact that too often they are trying to work up syntheses and formulate hypotheses on the basis of widely scattered sites in different natural environments dug and published with various degrees of plausibility. Most archaeologists today recognize that a more profitable kind of research is one that involves the study of restricted zones in considerable detail, in order to establish micro-traditions and measure adaptations to local conditions through time and by combining the best features of both ecological and taxonomic approaches. This type of research has barely begun in Iran although there are a few promising. beginnings in the Neolithic time range. When enough of these studies are available we shall have more success with our reconstructions. In the meantime, however, some of the “old” sites excavated before 1960 could profitably be tested again in the light of the more advanced archaeological technology now available.