Museum Object Number: 30-7-1

Engraving by T. Allom and E. Radclyffe in E.W. Brayley, A Topographical History of Surrey, Vol. 5 (1848), pl. opposite p.79

Engraving by T. Allom and E. Radclyffe in E.W. Brayley, A Topographical History of Surrey, Vol. 5 (1848), pl. opposite p.85

“Never forget that the most valuable acquisition a man of refined taste can make is a piece of fine Greek sculpture.”

This quotation, taken from a letter by Gavin Hamilton to Charles Townley, well illustrates the cultural climate in England at the turn of the 19th century. Hamilton, a Scottish painter, archaeologist, and dealer, may have had a personal interest in promoting Townley’s appreciation of classical antiquities, but he was certainly preaching to the converted. At his death in 1805, Townley’s collection was important enough to go to the British Museum, and he was only one of many affluent English gentlemen of the time—Sir John Soane, Sir Richard Westmacott, Joseph Nollekens, the Earl of Carlisle, the Earl of Egremont, the Duke of Richmond—who competed with one another in the acquisition of ancient objects. One of these distinguished collectors was Thomas Hope (1769-1831), who was born in Amsterdam but belonged to a family of Scottish bankers and used French as his first language. He traveled extensively from the age of eighteen, becoming not only acquainted but enamored with the cultures of Turkey, Greece, Syria, Egypt, and Italy. In 1795, the entire Hope family, fearing a French invasion of Holland, moved to England. In 1799 Thomas bought a house in London, on Duchess Street, that he remodeled and turned into a gallery for the display of his acquisitions, both contemporary and ancient. The gallery attracted many distinguished visitors, as well as many comments. In 1807, he purchased a country residence—the Deepdene, near Dorking, in Surrey (Fig. 2)—formerly owned by another well-known antiquarian family, the Howards and Arundels. This house was also enlarged and transformed to serve his collecting interests. Eventually, Thomas married and had children, one of whom, Henry Thomas Hope (1808-1862), inherited both his father’s antiquities and his passion for acquiring them (Fig. 3).

By 1884, the family fortunes began to decline. The Deepdene was leased in December 1893 to Lilian, Dowager Duchess of Marlborough, and then to others, until it was sold in 1920 and ultimately demolished. But the collection of ancient objects had already been sold and dispersed in 1917. Some pieces formerly owned by Thomas Hope continue to change hands even now, as visitors to the Metropolitan Museum in New York may have noticed: the Hope Dionysus, newly cleaned and restored, has recently become one of the attractions of the museum’s classical galleries.

Not all the Hope sculptures were found and auctioned at the same time. After the initial sale in July 1917, additional antiquities were discovered, on information provided by one of the gardeners, within the so-called sand caves that riddled the hill behind the Deepdene. These caves were actually tunnels excavated in the 1650s by a previous owner, Charles Howard, to be used for chemical experiments. They may have become storerooms for the Hope objects in 1898, when some marbles were transferred from the London residence; the Deepdene was at the time leased to the Duchess of Marlborough, who greatly disliked art, especially classical. This second lot was sold in September 1917.

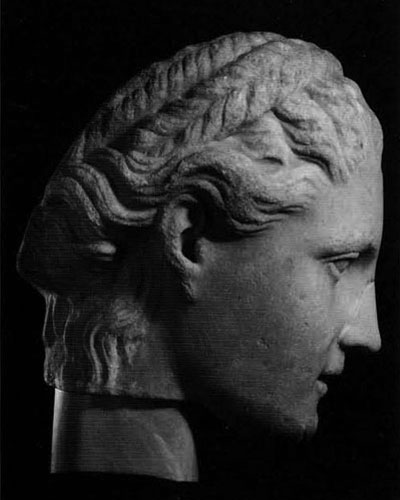

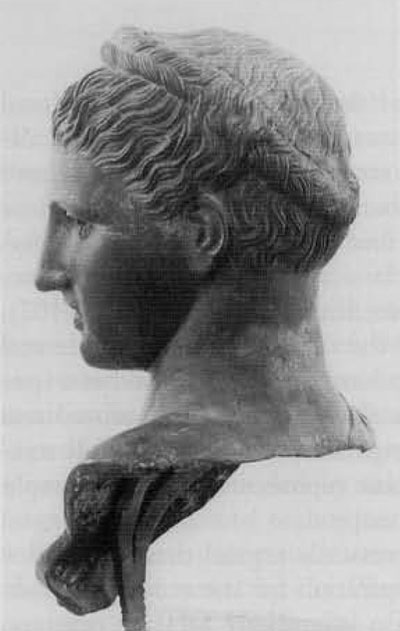

Among this group of antiquities was an over life-sized marble head of a beautiful female with a braided coiffure. It was acquired by the well-known art dealers Spunk & Son, who in 1930 sold it to the University of Pennsylvania Museum (Figs. 1, 4-6). It was published the following year by Edith Hall Dohan (Dohan 1931) who, made aware of the findspot of the piece at the Deepdene, raised the possibility that the head may have belonged to the Howards and Arundels. A publication of the Hope antiquities (Waywell 1986), which includes the head now in Philadelphia, states, however, that the marble was probably acquired by Henry Thomas Hope. The original ownership of the object is of importance to determine whence it may have come into British hands.

The Howards and Arundels were also members of a distinguished English family that eagerly collected antiquities. As early as 1613, Thomas Howard, the second Earl of Arundel (1586-1646), had traveled to Italy with the architect Inigo Jones, and in 1625 had sent his chaplain, William Petty, to Turkey and the Greek islands with the express task of securing classical sculptures for his employer. Among his acquisitions was even a piece from the Gigantomachy frieze of the famous Pergamon altar, the so-called Worksop torso (Haynes 1968). Given the wide range of travels by Petty and Arundel himself, a Greek or Asia Minor provenance for the Philadelphia head could not be excluded. Yet all indications are that the marble was indeed bought by the Hope family, although it cannot be pinpointed in any of the inventories of the Hope antiquities. If purchased by Henry Thomas Hope, the sculpture is certain to have come from Italy, his exclusive market. An analysis of the stylistic and technical features of the piece confirms this notion. I shall henceforth call it the Hope head.

The Hope Head

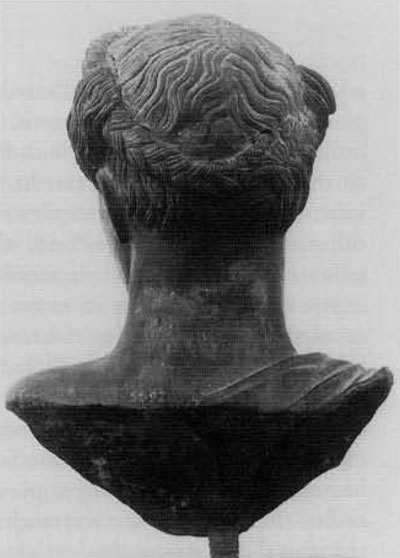

The recent reorganization of the classical gallery (now renamed in memory of Rodney S. Young) at the University of Pennsylvania Museum has brought the Hope head to a more accessible viewing level. It was once set up high against a wall, thus suggesting the height at which the head would have appeared to an ancient worshiper when the figure was complete, probably standing on a tall pedestal at the rear of a temple cella (main room). The new display, within a glass case, is less evocative of original conditions but has the great advantage of enabling the museum visitor to view the rear of the head—something an ancient spectator would not have seen.

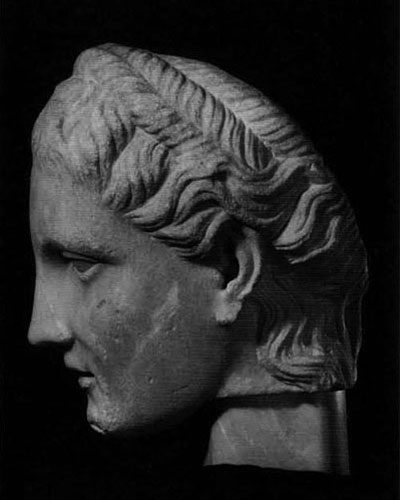

The back of the Hope head (Fig. 6) reveals not only some summarily carved details on the nape, but also a vast cavity where the entire rear portion of the cranium behind the circle of braids has been scooped out. This technical feature suggests that the sculptor was interested in lessening the weight of the marble, while confident that the setting of his figure would have made the omission invisible. In addition, the large hollow within the head ends in a funnel-shaped hole that perforates what remains of the figure’s neck. The hole’s irregular surface and relatively large size show that it was meant for a wooden pole that would have run through the total statue like a spinal column. It is therefore a logical inference that the image was made in the akrolithic technique, with the fleshy extremities of the body sculpted in stone and the draped parts carved in wood, then painted or gilded. This technique was often used in antiquity for colossal works in order to economize on both costly materials and time of manufacture. Such an akrolithic statue, moreover, would have resembled a gold and ivory (chryselephantine) image, like the much-admired Pheidian Zeus at Olympia or the Athena in the Parthenon at Athens.

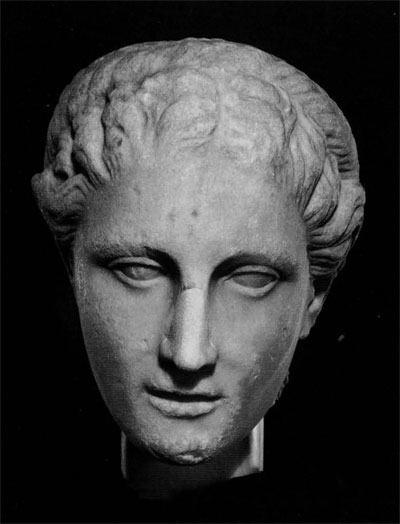

The large, heroic size of the Hope head and its idealized traits confirm that it was meant to portray a goddess. The face is a wide oval with heavy chin, full cheeks, and large eyes. The nose was restored in marble in modern times, but the restoration was based on traces of the original, vouching for its correctness. The mouth is slightly open, revealing both rows of teeth, as if to suggest breathing or speaking, thus increasing the appearance of naturalism. Even the asymmetrical cast of the features—eyes and ears of different sizes, mouth slanting and slightly shifted from the central axis of the visage—impart that touch of irregularity that is proper to any human face. Yet no human face could be so free from wrinkles or expression, no brow so smooth and serene.

The hairstyle, too, equally asymmetrical, is as complex as befits a divine person. Twisted strands of hair are pulled back from the forehead to disappear under the braids that encircle the calotre, while the remaining hair is rolled up onto the braids at the temples and over the nape (Figs. 4, 5). Additional strands flow down along the neck, presumably to the chest and shoulders. Although the back of the Hope head is only partially carved and articulated, it is possible to see that the coiffure was meant to terminate in a chignon, thus combining two or even three different hairdos: the rolled-up hair of figures like the Aphrodite of Melos, the loose style of matronly images like the Demeter of Knidos, and, in front, the “melon coiffure” accompanied by a high crown of braids typically worn by young girls.

This last coiffure takes its name (usually in German, Melonenfrisur) from its sectioned appearance that recalls the striated surface of a melon (Thompson 1963:38-39, 40-42; Higgins 1986:122-23, fig. 143a, b). Originating in Greece, probably in Attica, during the second half of the 4th century BC, this hairdo remained popular during the following century, although the high circle of plaits was progressively moved toward the rear of the head and eventually transformed into a tight bun above the nape. Highly favored by the Macedonian queens of Egypt, the fashion seems to have been discontinued during the 2nd century, only to be briefly revived toward the end of the 1st by Kleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemaic rulers, probably in a deliberate evocation of her dynasty’s glory days.

Because this development of the melon hairstyle can be chronologically supported by the historical dates of the Egyptian queens, the Hope head, with its articulated bundles of hair over the forehead and its high braids, was first dated to the late 4th or the early 3rd century BC and considered a Greek original coming from Greek territory. Even an actual purchase by Henry Hope in Italy would not have contradicted this origin.

The Circumstantial Evidence

Museum Object Number: MS3523

Museum Object Number: MS520

Yet a new awareness of the ways of ancient art and artists is beginning to assert itself in present studies. We have come to realize that not all sculptures of Roman date were inspired by a specific Greek model which they duplicated more or less accurately and faithfully. Rather, most masters working for an Italian clientele used a general classical vocabulary that they could combine and recombine into their own idiom, producing compositions that may have looked Greek but were instead proper expressions of a Roman message and ideal. Even different Greek styles could be juxtaposed, more or less harmoniously, into eclectic works that should be judged not as erroneous or misunderstood copies, but as responses to definite contemporary demands and tastes. To he sure, true copies existed, even cast from molds taken from earlier creations. However, the decision to copy was not necessarily based on the earlier date or the ethnic origin of the prototype, since unquestionably Roman statues were also reproduced and adapted, often for religious or decorative purposes.

As early as the late 2nd century BC, some of these decorative objects were manufactured on Greek soil for the Roman market, as shown by the cargoes of several wrecked ships that have been recovered during this century. The recent exhibition, in Bonn, of the contents of a vessel that sank off the coast of Tunisia (the so-called Mandia wreck) has amply proved the case (Ridgway 1995). But a large number of Greek sculptors also moved from the Greek islands and Athens to Italy to establish workshops where they could satisfy requests more directly. In particular, they produced cult statues for the Romans who, after their exposure to Greek practices, had acquired a taste for marble representations of the gods to replace their terracotta deities of old. The first such idol in stone to be erected in Rome was an Apollo by Timarchides to which the firm date of 179 BC can be assigned.

Not many of these temple images are preserved, if we restrict the definition to statues that were excavated within a religious structure or find definite mention in literary sources. Seventeen have been catalogued (Martin 1987) according to these criteria, but more could be included by taking into account overlarge size, style, and technique. As already mentioned, several of these cult statues were akrolithic, and most of them were inspired by the Pheidian models of the 5th century BC. The University of Pennsylvania Museum possesses other marble heads that meet all the specifications and come from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis at Nemi, near Rome; but the Hope head could also be included if an item of circumstantial evidence from Herculaneum can be accepted as a clue.

One of the mansions buried by the Vesuvian eruption in AD 79 was the “Villa of the Papyri” at Herculaneum. (It received this name when first excavated because it was found to contain quantities of scrolls in both Greek and Latin.) Scholars have advanced various suppositions as to its owner on the basis of his learning, but no consensus has been reached, so the more generic appellation for the villa prevails. It has acquired special resonance in the United States, because it has been faithfully reproduced in Malibu, California, to house the J. Paul Getty Museum.

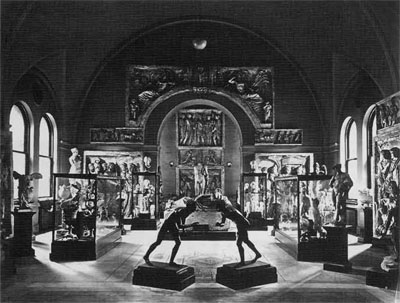

In keeping with his Greek and Latin erudition, the Herculaneum villa’s master surrounded himself with statues, berms, and portraits in bronze and marble. These are now kept in the Naples National Museum and have in turn been duplicated for the Getty grounds, where they occupy the spots in which they were originally excavated. A few such modern reproductions, acquired in earlier times (Fig. 7), even embellish the open areas of the University of Pennsylvania Museum (Fig. 8a,b). Some of the Herculaneum sculptures, for instance a bust of the famous Spearbearer (the Doryphoros) by Polykleitos, copy undoubted Greek classical originals. Others are portraits of Hellenistic rulers whose identity is not always certain; and a few heads exist for which no specific identification is possible, although some have been proposed. In addition, a certain number of generic types—satyrs, athletes, and animals—also stood, as appropriate, within the colonnaded garden (the “Large Peristyle”) with central oblong pool that is one of the main architectural features of the villa (Fig. 9; see also Warden and Romano 1994).

Near the end of the pool closer to the living quarters a bronze head of a woman was excavated on April 29, 1756 (Mattusch 1996: 102-21). Although partly damaged, the piece was easily and correctly restored.

It was also provided with a modern bust and a swag of drapery that should not, however, affect our understanding of the only ancient part, the head. This latter depicts a young woman of normal size, wearing her hair in a plait that encircles the cranium (Figs. 10, 11). It is the only parallel I have been able to find for a peculiar detail of the hair arrangement on the Hope head—the long strands pulled up at the temples to overlap the braid. All other instances of the coiffure, whether in Greek originals or in Roman copies, in stone or in metal, show the crown of braids free for its entire course. Given the rarity of the motif, it is logical to conclude that the two heads—the marble one in Philadelphia and the bronze one in Naples—are somehow related.

To be sure, the head from Herculaneum is not identical to the Hope head: the facial oval is smaller and narrower, as befits a younger person; the braid is single, rather than double; the waves along the neck are omitted; and the hair over the forehead is not as clearly articulated into the sections of the melon coiffure. Yet the peculiarities of the hairdo at the back make me think that the sculptor who cast the Herculaneum bronze did not have a clear view of its prototype and therefore improvised according to his understanding of the coiffure. He made the single braid originate from the right half of the head, rather than from the center, and brought it back, as it were, to its point of origin (Fig. 11). But he made no apparent provision for the remaining strands on the left half, which should have been as long as those plaited on the right side. Thus, the hair below the braid, over the nape, looks short, as if either coining down from the top of the cranium, or combed upward and tucked in under the plait.

Illustration by David Gilman Romano

The findspot of the Villa of the Papyri head shows that the bronze was set up in the clear, for all-around inspection. The ancient viewers would not have questioned whether its hair arrangement was logical or not, and from the front and sides the effect was comparable enough to some classical (early 5th century) renderings to pass muster (see Ridgway 1970: figs. 74-102). But the wings of hair at the temples remain unique and are distinctive enough to have been understood as a specific quotation. I believe that the prototype quoted was the Hope head in its original appearance as a full statue—a divine image of some repute, standing in a temple probably located in Rome.

National Museum, Naples, no. 5592

National Museum, Naples, no. 5592

It could be theoretically argued that the smaller bronze head was the inspiration for the colossal marble one, but this supposition is unlikely for two reasons. The bronze was a relatively minor object within a much larger sculptural program used in a decorative fashion for a private villa; and its date should be no earlier than the late 1st century BC, since several works from the same complex (e.g., the well-known Herculaneum “Dancers”) imitated Augustan prototypes. A second possibility—that both heads independently reflect a Greek classical model—is equally improbable, since a plausible date for the Hope head is around 100 BC.

As already mentioned, the serene appearance and the heavy facial features of the marble head recall 5th century styles. Yet the melon coiffure did not appear in Greece until the mid 4th century, and the arrangement with braid-crown did not survive third. The open mouth showing both sets of teeth is typical of 2nd/1st century BC works (see Martin 1987: p1. 6), and the eclecticism revealed by the combination of three hairstyles (one of them—the single braid with lateral origin—much earlier than the others) is in keeping with this latter phase. Finally, the akrolithic technique, although practiced in Greece, was widely used in Italy for cult images, which were not even partially made in stone until the Late Republican period. These various pieces of evidence combine to show that the head in Philadelphia—a superb work by a Greek sculptor active in Rome or its environs at that time—must indeed have been bought in Italy by Henry Thomas Hope.

Too many Greek masters are known to have been in Italy around 100 BC to allow an informed suggestion about the maker of the Hope head. Can we at least name the subject of his work? The very eclectic character of the piece makes it difficult to state who the specific deity might have been; Heraduno, Aphrodite/ Venus, Athena/Minerva, Artemis/Diana, even Persephone/Proserpina are all possible but unprovable identifications. Equally plausible are a number of personifications like Fortune, Hope, Valor, and other concepts anthropomorphized and venerated by the Romans. For our purposes, suffice it to know that a rare objection Italic cult image of a goddess—inhabits the Ancient Greek World Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania

The Roman conquerors of Greece are known to have taken home vast quantities of Greek sculptures captured as war booty in their expansion to the east during the last two centuries before our era. In addition, a certain snobbism current among English collectors made them prefer a Greek labels to a Roman one even when an Imperial date for some of their pieces was obvious. Thus, any sculpture of good quality was automatically considered a Greek original, free from the slight taint of being a “Roman copy of a classical Greek prototype.” Such prejudices can still he found today, even in some scholarly quarters.