Islamic archaeology did not fully develop in Iran until after 1930 when the French monopoly of excavation in that country expired and the gates were open for all. The digging of the Islamic levels by the French at Susa was ably published in 1928 by R. de Koechlin but not preceded by excavation reports. Now the tendency has been to publish excavation reports with little to follow as thorough as M. de Koechlin’s publication. After 1930 American excavations were commenced at two very important Islamic sites: Istakhr and Rayy. The first was undertaken by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, the latter by the University Museum, Philadelphia with contributions from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The work at the former site was reported in the briefest kind of way and the latter by only incidental references. These excavations were followed by those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art at Nishapur, a city that flourished especially in the Samanid and early Seljuq periods. Several reports and articles have appeared on this work in the Bulletins of the Metropolitan Museum and a full account of the pottery is in the hands of the editor. The second world war brought a change of policy in regard to the Metropolitan Museum’s field activities, and properly supervised excavation came to an end in Nishapur—a particularly great loss from an architectural point of view. Since that war there has been little American activity in excavating Islamic sites, an exception being an extension of the work undertaken by the Peabody Institute, Harvard University, at the pre-Islamic site of Tepe Yahya, this extension being the clearing by Andrew Williamson of Tepe Dasht-i Deh which is nearby.

In 1968 the German Archaeological Institute of Iran thoroughly excavated the remains of a kiosk built by the second Mongol ruler: the Il- Khan Abaqa (1265-81). They were fortunate in finding glazed tiles some of which were dated 671/ 1272. By careful study the wall decorations were reconstructed and published. This brings to mind the extraordinary wealth of material, both ceramic and metal, which is ascribed to dates immediately before the Mongol invasion. Granting that the Mongol invasion was truly catastrophic and that the period immediately preceding was extremely productive of works of art of great merit, it is hard to believe that the latter part of the thirteenth century was as blank as museum labels would have us believe. Furthermore, the time of the great Seljuqs is almost equally barren when judged by the same gauge. In this matter, excavation might truly help where “art history,” based on a few dated pieces, fails.

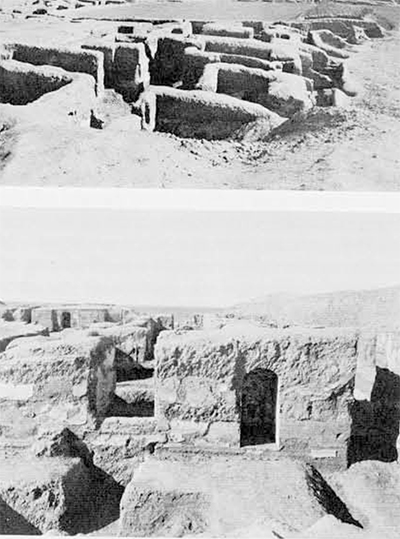

The main continuing excavation of an Islamic site is being pursued by the British Institute of Persian Studies at Siraf on the Persian Gulf, where they have exposed a number of interesting buildings including a mosque with five major periods of construction, a residential quarter, a bazaar, and a kiln site. They are now investigating some pre-Abbasid buildings, which should yield some much wanted information. The results have been published in a series of articles in Iran, vols. VT-DC, with excellent plans and illustrations.

The excavations mentioned above by no means take the place of the work relinquished at Rayy and Istakhr. Further excavation at Istakhr should be particularly interesting in that it might well give more information on the transition from the Sassanian period to the Islamic. It would be particularly fortunate if such work could be again undertaken, thus enabling the results of the work done almost forty years ago to be fruitfully integrated with any new discoveries.

In contrast to the archaeology of Iran’s remote past in which excavation plays such a predominant role that without it we can know nothing of how certain ancient peoples lived, developed, and moved, the archaeology of the Islamic period is of a different nature. For this period, excavation plays a more supplementary role for it is but one way of several that add to our understanding of a mode of life not so greatly different from that of the grandfathers of the Persians of today. Archaeological research therefore has to be very wide in scope in such an historical and literate era. The various investigations and the researches of historians, philologists, epigraphers, architects, numismatists, art historians, and social historians, as well as of field archaeologists, are among those that have to be coordinated. The necessity of integrating and modulating these various specializations is recognized by publishers of such books as the Cambridge History of Iran where, in the fifth volume, the Seljuq and Mongol periods are discussed from several points of view. A particularly good example in that volume is a fruitful synthesis written by Oleg Grabar on the visual arts. The excavations at Rayy, to which but the most cursory references have been made, nonetheless produced, through the industry of George C. Miles of the American Numismatic Society, The Numismatic History of Rayy, information the scope of which far exceeds merely cataloguing coins.

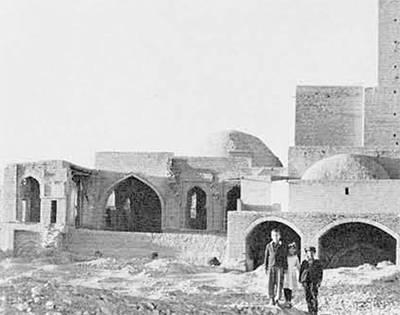

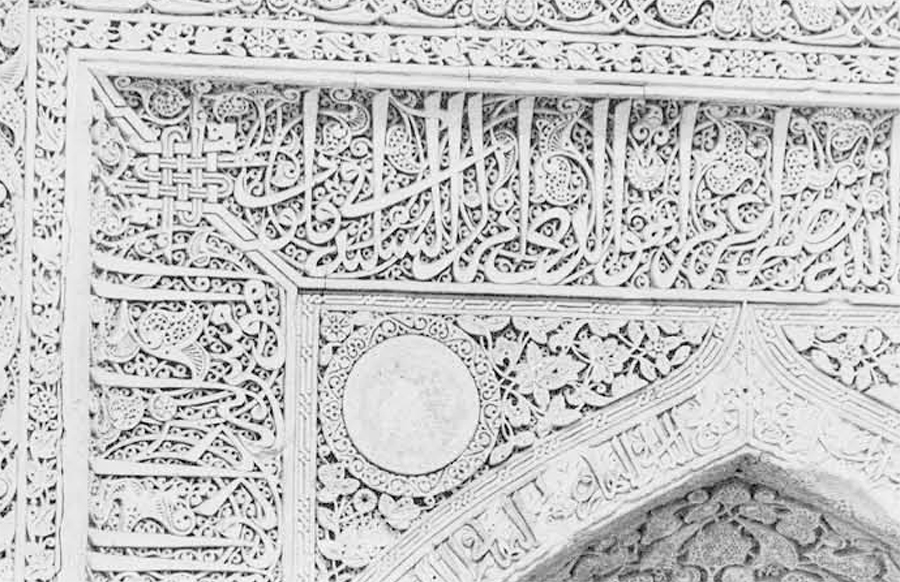

Although some of the exploratory journeys that are being made do not entail actual excavations, they are nonetheless archaeological. The buildings of the Islamic period are often of great age and many of them, whether a millennium old or merely a century old, should be recorded, especially as a great number of them are disintegrating. Work of this nature was well launched many years ago by the first director of the Iranian Archaeological Service, M. Andre Godard, who, an architect by training, brought to this task the technical understanding which is necessary for recording such buildings, and even more necessary for carrying out restoration in an accurate way. The results were magnificently published in Athar–e Iran (1936-1949), a series which attained a standard of excellence in illustration that regrettably has not since been approached. The work done by him, by Arthur Upham Pope, Donald Wilber and other assistants, published in The Bulletin of the Iranian Institute of America, and the late Myron Bement Smith, who studied brick architecture in the most painstaking way and made it public in Ars Islamica, has by no means been in vain. Carrying on from preliminary studies, Lisa Golumbek has turned her attention to the Turbat-i Shaikh Jam, publishing it in depth—combining the results of inscriptions within the building with information from an appendix to a thirteenth century literary text, the Maqamat-i Aulid-i Shaihk-i Jam and then dealing with other shrine complexes. In Iran a number of such problems remain to be dealt with, including the relationship of function to building and the development of architectural concepts.

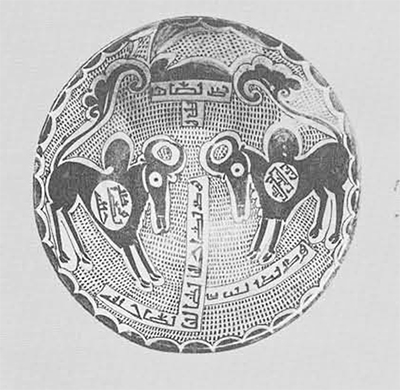

Museum Object Number: 319259

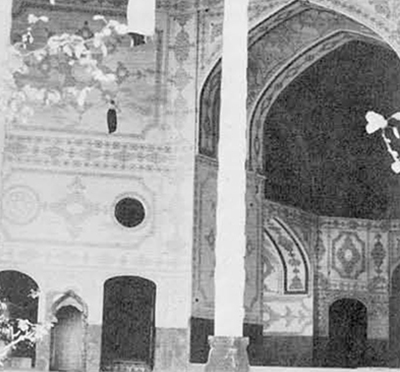

Of great importance is the continuance of surveys which fortunately are being undertaken in various parts of the country. These have brought to light several buildings not hitherto generally known as, for example, the Seljuq towers found and well published by David Stronach and Cuyler Young, Jr. There are surely more buildings of importance to be discovered. Surveys of this kind have become an almost international affair with members of various institutions undertaking the task, publishing the results, whether done individually or in cooperation, in journals such as Iran and the Archeologischen Mitteilungen aus Iran, N.F. The buildings examined are of various dates and both religious and secular. At the present time, in the course of restoring one such building, the Hasht Behisht at Isfahan, the Safavid core has been stripped of its Qajar alterations—and this is a reminder that what is stripped away can also be of interest. This and other important restorations are being undertaken with Italian help. Some of them are described and illustrated in Travaux de restauration de monuments historiques en Iran, ed. G. Zander, Rome, 1968.

The destruction of architecture of the Qajar period, although sometimes necessary for present day requirements, should be limited as much as possible to inferior examples. There was a definite style during the nineteenth century and such was true and meaningful of Iran of that time. For this reason alone its architecture should be both more fully recorded and preserved together with its tile and painted decoration and gardens. In the surveys, pigeon towers have not been overlooked but some attention might be given to the monumental ice walls which, with their elaborate brick decoration, are probably doomed as modern methods of refrigeration gradually take over.

Museum Object Number: 180429

A great need exists for further investigation into the whereabouts of potteries. It is extraordinary how little we know of large related groups that obviously come from various centers. To name but a few, we do not know for certain where the so-called Kubachi ware was made—was there more than one center? We know little of the places of manufacture of many types of Safavid pottery. Of earlier periods, no kilns have yet been found at Rayy; none are known that produced the so-called Garrus and Yasukand wares, or those of Amol and Sari. It is evident that, apart from very specialized types of pottery, such as luster, which come from but one or two sources, others were made in various places within certain geographical areas. These matters and the geographical spread as well as the whys and wherefores of popularity require a great deal of study. There are specific though perhaps very limited problems such as why Iran, a cobalt producing country, used it in its glazed pottery only during and after the Seljuq period, whereas it was definitely used in Mesopotamia, which produces no cobalt, in the ninth and tenth centuries. What appears to be necessary once again is to emulate Sir Aurel Stein who in his Archaeological Reconnaissance in Northwestern India and Southwestern Iran published in the most excellent way, using color, the sherds carefully catalogued from specific sites. An extension of this type of work done in the same painstaking method would be a great contribution.