Although numerous Israelite cities have been excavated in Israel, the relatively small proportion of the total city area excavated and the fragmentary state of the remains have made it practically impossible to obtain a complete picture of such a city. From this point of view, the excavations conducted at Tel Beer-sheba in 1969-1976 (by an expedition of the Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology, headed by the late Prof. Yohanan Aharoni) were advantageous in two respects: first, during eight full seasons the excavators concentrated primarily on uncovering the upper Israelite city; second, these extensive efforts were applied to a relatively small, compact site, whose area does not exceed 12,000 square meters, thus enabling the exposure of virtually the entire city. The ensuing urban picture is complemented by evidence from previous excavations of Prof. Aharoni in the royal Israelite citadel of Tel Arad (1962-1967).

The ancient city of Beer-sheba was erected on a hilltop located about half way between the Hebron and Beer-sheba rivers and close to their junction. The hill is strategically located, commanding a good view in all directions, its steep slopes rising above the wadi beds providing a certain amount of natural defense even prior to its fortification. Another attraction of the site is the western breeze which starts blowing across the hill late in the morning, alleviating somewhat the scorching heat of the Negev sun, particularly in the summer.

Elements of Urban Planning at Beer-Sheba

The study of the elements of urban planning is based primarily on the results of the excavations of Strata III-II. However, similar principles were noted in the plan of Stratum V, the first city established at the site, which is dated to the United Kingdom.

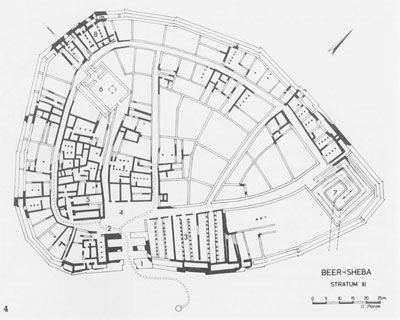

The outer frame of the city is its fortification system. In Strata V-IV it was a solid wall, which was replaced in Stratum III by a new type of defense erected on its ruins: a casemate wall constructed of two thick parallel walls, the intervening space partitioned by thinner walls into long narrow rooms. Concurrently with the erection of this wall, the city gate was also renewed, although its plan does not differ substantially from that of the previous gate: two face-to-face ‘E’s, separated by a wide passageway, flanked by large rooms on either side. The outer gate of Stratum V was no longer used, and its foundations were utilized as retaining walls for the earthern ramparts which were renewed and elevated, now surrounding the front of the gate itself. Instead of the former outer gate, the frontal walls of the main gate were thickened, converting them into defensive towers.

The water supply system at the northeastern corner of the city (which has been only partially excavated) was essentially part of the defense system. It probably dates back to Stratum V. The descent to the underground water source was by a staircase built along the face of a square shaft, probably continuing through a tunnel dug under the city wall to reach the ground water level—similar to the systems discovered at Megiddo and Hazor. These huge water systems, whose erection required extensive engineering ability and vast investments of manpower, were designed to prevent the enemy from gaining control of the fresh water source. By providing access to the source of water from inside the city they strengthened the ability of the inhabitants to withstand a prolonged siege.

The second element of urban planning in Beer-sheba during the Judean Monarchy was the street-grid. Since all traffic in the city eventually led to or from the city gate, the grid was planned accordingly, the streets spreading out fanwise from the gate area. There was also a peripheral street circling the entire city, parallel to the city wall and about 10 meters inside it, the intervening space being occupied by a row of private dwellings. The center of the city was divided into several quarters by cross streets joining the city square in front of the gate. In the gatehouse itself the gate chambers were open to the passageway and furnished with built-in benches. Together with the city square, these gate rooms provided a focal point for the daily civil requirements of the citizens—an ideal place for ministers, judges, merchants and prophets to carry out their functions. The city square itself may have been used as a market place. Adjoining this square were two large courts which were probably used as a caravanserai.

The streets of Beer-sheba, which are not more than two meters wide, are characterized by the continuity of their lines, uninterrupted by “trespassing” houses. This neatness of layout is particularly remarkable when it is compared to the plans of contemporary Israelite cities such as Tell Beit Mirsim and Tell Nasbeh, where the width of the streets is uneven, their course twisting around some of the houses and sometimes even blocked by them.

Not less surprising is the near-perfect drainage system discovered under the streets, The system includes plastered gutters leading the rainwater from the roofs down the walls of the houses into a network of subsidiary and primary channels, eventually joining up with the main channel passing under the gate and out of the city. The benefits of this system were two-fold: it prevented an accumulation of rainwater inside the city which could have undermined the buildings—a danger inherent in the simple and economical building methods used in Beer-sheba, where the rough stone foundations were held together by clay mortar, and the upper structures were built of sun-dried mud brick. If these walls were exposed for any length of time to standing water, the mortar and bricks would have dissolved, causing the collapse of the entire building. ❑One of the aims of the drainage network was doubtless to avoid this eventuality. At the same time, the system was used to collect and store the run-off water by leading it through the main drainage channel into the ancient well located just outside the city gate. Apparently the Elders of the City understood that they could thus enrich the natural underground water reserves in the area—perhaps the earliest example known to us of a system for increasing the underground water supply by channeling rainwater into it.

The most important public building in Beer-sheba was no doubt the storehouse complex at the right of the city gate. Covering an area of about 600 square meters, it consists of three units, each divided into three long, narrow halls by two rows of stone pillars, enabling the use of the side rooms for storage and the central hall as a passageway. In addition, the spaces between the pillars allowed light and air to enter through side windows over the central hall, whose roof was presumably somewhat higher than the side halls.

Hundreds of pottery vessels found in the destruction level of Stratum II are evidence from which the organization of the storehouses may be studied. In each of the six side halls used for storage there was a great variety of vessels, indicating that many different kinds of food products—oil, wine, grain, cereals, etc.—were stored there and that there was no functional differentiation between the halls. We may assume that each room (or pair of rooms) served a different administrative unit, for example, a military or transport unit, or the residence of the governor of the city. Since in addition to the storage vessels there were other types of utensils for measuring, preparing and cooking the food (including grinding stones and mortars), it is clear that the storehouses were active dispensing centers; the food was not only stored there but prepared for delivery in accurately measured quantities. Perhaps even the pottery vessels themselves were part of the inventory and were lent out to some of the units who received their rations from Beer-sheba. The central hall of each storehouse (in which no vessels were found] was obviously a passageway for the donkeys and mules of the suppliers and recipients; some of the stone pillars were drilled with holes near the corner which could have been used to tie up the pack animals while loading and unloading; in the meantime, they could be fed and watered from the basin-shaped installations built into the spaces between the pillars.

The finds in the storehouses of Beersheba shed light on the function of similar buildings found in other parts of the country which have frequently been misinterpreted as stables—at Megiddo, for example. This misunderstanding was caused by several factors, including the fact that the excavators found the storehouses empty of any objects which might have helped them to clarify their function.

The finds in the storehouses of Beersheba fit in nicely with the contents of the Arad inscriptions, which are essentially “delivery orders” specifying quantities of various types of food and drink destined for the military units patrolling or encamped in the region. Thus the function of the storehouses was to provide a supply base for the military forces and the royal administration, and all those who ate at the king’s table.”

Another public building, located opposite the city square, was the residence of the governor. The largest and most beautiful building in Beer-sheba, it contains spacious reception halls, dwelling quarters and a service unit with its own storeroom and kitchen. Close by was very likely the house of the Commander of the Guard, built against the city gate, making it possible to climb by way of its roof to the gate towers and the ramparts on top of the city wall.

An exceptional building, differing markedly in size and plan from the private houses, is what we have termed the “Basement Building.” Built in Stratum II, its foundations, 4-5 meters deep, went clear down to bedrock, destroying all previous remains. Some of the spaces between these foundations were filled with earth while others were discovered empty; since it is assumed that this building had a public function, these basement rooms may have been wine cellars. This unique building may perhaps supply a partial answer to one of the most perplexing questions which arose during the Beer-sheba excavations: Where was the temple of the city located?

In view of the ancient cult tradition connected with Beer-sheba which has been preserved in the Bible, there is no doubt that somewhere in the settlement there was a sacred precinct. The discovery of an Israelite temple in Arad is archaeological corroboration of the scriptural references to temples in the provincial centers. It was therefore a great disappointment to us when, after four seasons of excavations, there was still no clue as to the location of Beer-sheba’s temple. The turning point came in the fifth season, when a horned altar was unearthed, the largest and most impressive altar of this type ever found in Israel. Alas! It was not found in situ.

Composed of several ashlar blocks, neatly fitted together, it had been completely dismantled and its stones used as building material in one of the walls of the storehouses. We considered this intentional destruction a hint that the temple itself may have suffered a similar fate and all traces of it obliterated. Beer-sheba had evidently witnessed a religious reform such as that known from the Bible during the reign of Hezekiah (2 Kings 18), whose edicts were intended to abolish worship in the temples of the provincial towns and concentrate all religious rites in the temple in Jerusalem. The “Basement Building” described above provides valuable

(albeit negative) evidence of the location of the Beer-sheba temple, which was replaced by this odd structure with its unusually deep foundations, after the temple had been taken apart stone by stone, leaving nothing but patches of the chalky white floor of its courtyard. At the same time, the magnificent altar that had stood in the center of this courtyard was also dismantled and its stones used to repair the storehouses; a few of them were found buried under the glacis outside the gate, which was also renewed at this time. These alterations and others mark the end of Stratum III and the beginning of Stratum II, the final level of the Israelite city, which was destroyed in a violent conflagration by the Assyrian king Sennacherib in his campaign to Judah in 701 B.C.

The rich data gathered from Beer-sheba now enable us, for the first time, to reconstruct the character of an Israelite city, Apparently, the cities of this period—in contrast to those of today—were not residential areas for large populations but regional centers for the royal administration, accommodating its storehouses, treasury, military headquarters and the like. The common people did not live in cities but in scattered villages and hamlets near their fields and grazing lands. Planned royal cities like Beersheba were intended for the occupancy of the military, political, economic and religious elite of the regional “capital.” Only such functions would have been important enough to justify the expenditure required to plan and erect a complete city and to surround it with such massive fortifications.

If we assume that the unexcavated portion of Beer-sheba was substantially of the same character as the areas already excavated, there would have been no more than 50 dwelling units, accommodating approximately the same number of families, their breadwinners undoubtedly all on the royal payroll.

Our premise that the dwellings were occupied by servants of the administration is supported by the layout of the houses. Most of these were built according to the Israelite “four-room house” plan, although their arrangements differ somewhat from the typical house of this type. What is especially significant at Beer-sheba is the fact that the rear room (the most important part of the house) was at the same time one of the casemates of the city wall—in other words, an integral part of the city’s fortifications. Such a plan naturally presupposes a great deal of faith on the part of the administration towards its functionaries. It may be assumed that each householder was responsible for the care and maintenance of that part of the city wall which adjoined his dwelling. Such a relationship between domestic life and mili tary defense is understandable only if the socio-political structure of the urban population was as outlined above, i.e. that the entire working population consisted of administrative personnel.

The Royal Citadel at Arad

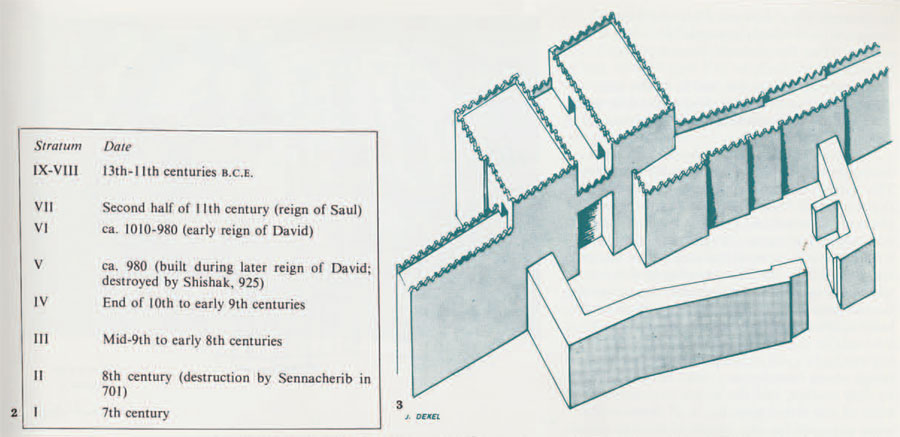

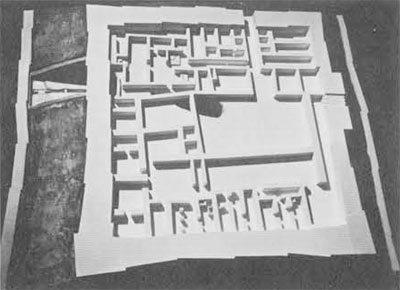

The Israelite citadel at Arad, situated on a hilltop at the eastern end of the Beersheba—Arad valley, extends over about 2,500 square meters. The citadel was first erected in the 10th century B.C., during the period of the United Monarchy; it was destroyed and rebuilt six times before the end of the Monarchy. During all its history, however, the basic plan was maintained on the same lines.

In spite of the rounded contours of the natural hill, the citadel was built as a square, measuring 50 x 50 meters. It was encircled by 4-meter thick walls, either casemate (Strata XI, VII, VI) or solid (Strata X-VIII]. The case-mates themselves were used for storage and habitation, as evidenced by the pottery found inside them.

In the center of the citadel was a large courtyard. To its south was a row of dwellings which adjoined the citadel wall and were characterized by a typical feature of the Israelite house: a row of pillars separating a long open courtyard from its adjoining roofed-over room. The northeastern corner of the citadel was designated for worship, and the Israelite temple erected there was in existence throughout most of the Monarchy period, It was probably a sacrificial and offering center for the citadel’s inhabitants and the population of the surrounding settlements. Near the temple and adjacent to the gate were the storage halls of Arad. From the absence of the rows of pillars typical of the storehouses in Beer-sheba, we may assume that these were closed storehouses, perhaps the citadel’s magazines.

During the restoration and preservation of the remains of the citadel in Arad, a short excavation season was conducted in the gate area, at the east in order to clear the gates of Strata XI-X. It was revealed that the narrow passage through the gate of Stratum XI leads through one of the casemates into the citadel, while in Stratum X a huge gate was built in the middle of the eastern, solid wall, with a direct entrance defended by a pair of towers protruding outwards and deep gate rooms inside the entrance. The towers of this gate and the adjoining wall, partly restored by us, demonstrate the strength of the facade of the citadel.

Water was supplied by bringing it through a channel from outside the citadel (probably from an open reservoir which was filled during the rainy season). The water was channeled into underground cisterns which were discovered under the floor of the temple courtyard. By means of such plastered cisterns it was possible to store sufficient water to supply the needs of the citadel for an entire year, making it independent of any outside sources.

Summary

The comparison of the Arad citadel plan to the city plan of Beer-sheba reveals some remarkable similarities: in both places the planners gave priority to the royal administration, reflecting the military, cultic and economic requirements of the kingdom.

On the basis of these characteristics Arad and Beer-sheba may be compared with other Israelite sites from the period of the Monarchy. A review of the excavated sites indicates a different degree of planning at each site. It is noteworthy that in the less well-planned sites there are fewer public buildings and more private dwellings. According to the archaeological finds and the literary sources, we can classify the cities of Israel into four types based on the standard of planning. The first type includes the capitals, especially Jerusalem and Samaria. These cities had a separate acropolis where the king’s residence was located together with the rest of the royal buildings. As capi tal cities, dwelling quarters were also required for the population which supplied services to the court: merchants, craftsmen, servants, etc., who lived in the lower city at the foot of the acropolis. To this category belongs also Lachish, where the acropolis was separated by a wall from the rest of the city.

The second type of city is the regional administrative center. In these centers, which differed in size according to their location and the size of the region served, we find only public buildings and a few dwellings for the use of the functionaries: army officers, tax collectors, storehouse managers and the priests of the royal temple. Excellent examples of such centers are Beer-sheba and Arad, to which we should add Hazor Strata X-VI and Megiddo Stratum IV, and probably the Israelite city at TeI Dan.

The third type is the fortified site in which the standard of urban planning is low, but nevertheless includes some administrative units. An example of such a site may be Beth-shemesh IIa.

In the fourth type, urban planning was practically non-existent and there are no royal public buildings, but nevertheless they are fortified; in other words, their only public function was military; such cities were discovered at Tell Beit Mirsim and Tell Nasbeh. The lack of planning is clearly reflected by the twisting fines of the streets and lanes. These cities were fortified not because of their intrinsic importance but due to the need of the central government to establish a regional fortification system.

These four types, which represent the various standards of planning as influenced by the function of the city, may be contrasted to the many unwalled settlements and villages in which most of the agricultural population lived during the Judean Monarchy.