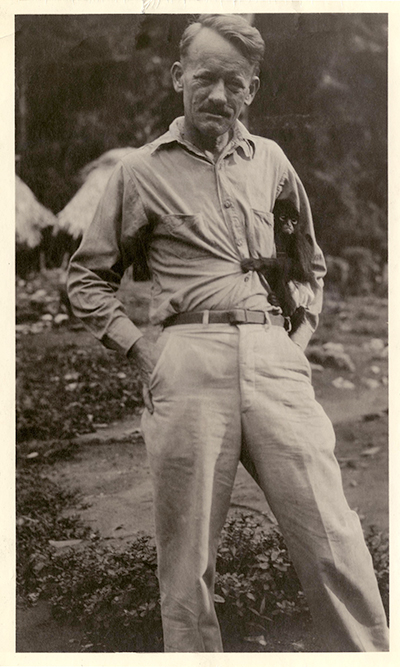

This is the story of Dr. John Alden Mason (1885–1967), one of the last of the great generalist anthropologists of the 20th century. We know him at the Penn Museum for his work in anthropological linguistics in Mexico, and as an archaeologist of the Americas who excavated at Piedras Negras in Guatemala and Sitio Conte in Panama.

In this article written on the 50th anniversary of his death, I will recount highlights of the life and career of my friend and mentor, a gentleman who was, truly, an “anthropologist for all seasons.” In order to understand the tremendous and unsurpassed breadth of anthropological expertise that Alden possessed, we must examine his early professional education and the cast of famed late 19th- and early 20th-century anthropologists with whom he studied and worked.

Founders of American Anthropology

After his birth in 1885, J. Alden Mason (which he preferred to his full name) was raised in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia where he completed his schooling at Central High School. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, where in his sophomore year he enrolled in the first course ever offered in Anthropology at Penn, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1907. This period encompassed the origin of academic anthropology in the United States, and all was not easy for an aspiring anthropologist. After losing a coveted Harrison Scholarship to Frank Speck, Mason obtained a position at the Penn Museum as photographer to Curator George Byron Gordon. This allowed him to earn money for his future education. Dr. Gordon was an important figure in American archaeology: he conducted ethnographic research in Alaska and excavated at Copán in Honduras. From 1910 to 1927 he was Director of the Penn Museum and supported important excavations such as Beth Shean in Israel and Ur in Iraq. Gordon also helped to establish the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania in 1913.

From 1908 to 1910, Mason took graduate courses from Speck as well as from Dr. Edward Sapir, who had arrived at the Penn Museum in 1908 from Berkeley. He spent the 1909 field season with Sapir, working on the Uintah (western) Ute tribal language and culture. His contacts with Frank Speck—a student of Franz Boas and an anthropological ethnologist and linguist whose research interests included Native American cultures such as the Cherokee, Iroquois, Labrador Eskimo, and Yuchi people—and Sapir—a German-American anthropologist who was one of the founding fathers of anthropological linguistics— were to have an enormous influence on his career.

Mason’s efforts were rewarded with a scholarship to attend the University of California at Berkeley, one of the preeminent centers for the emerging field of anthropology. He earned his doctoral degree with the famed cultural anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber, who had distinguished himself in anthropological linguistics as well as archaeology. Dr. Kroeber trained under Boas at Columbia University. Boas is often called the “Father of American Anthropology” and was a founder of the American Anthropological Association. He would unite cultural anthropology, linguistics, archaeology, and physical anthropology (biological anthropology) into the modern four-field approach to anthropology, still taught in the Department of Anthropology at Penn and other universities.

Early Career, Ethnolinguistics, and Folktales

Mason excavated two sites in Central America— Piedras Negras in Guatemala and Sitio Conte in Panama. Both were located in dense jungle environments, providing unique challenges.

Mason’s doctoral dissertation, an ethnographic investigation of the Salinan Amerindian group of California, led to his first published monograph, The Ethnology of the Salinan Indians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1912). After completing his doctoral degree in 1911, he worked for two seasons (1911–1913) as Penn’s representative to the International School of American Archaeology and Ethnology under Boas in Mexico. In Jalisco, his first major expedition, Mason researched the ethnography and language of the Tepecano Indians, hoping to write a grammar of their language. By this time, he had already been a student of the pioneers of modern anthropology: Gordon, Speck, Sapir, Kroeber, and now Boas.

Following his work in Mexico, and even with the support of Boas, bad luck intervened—he was unable to find an academic appointment. Sapir and Boas arranged for him to conduct expeditions to the Great Slave Lake in 1913, as well as to work in Puerto Rico from 1914 to 1915. In Puerto Rico, Mason discovered a collection of traditional stories of Juan Bobo, a folkloric character about whom hundreds of tales, riddles, songs, and books had been written spanning almost two centuries. The series was first published in the United States in 1921 in the Journal of American Folklore. He collected about 70 stories from Puerto Rican schoolchildren, which were published over the following 14 years. Story titles included Juan Bobo and the Riddling Princess, Juan Bobo Heats Up His Grandmother, and Juan Bobo Delivers a Letter to the Devil.

Mason Is Called to the Penn Museum

Because the emerging field of anthropology was small and jobs were scarce, Mason survived on funds remaining from his grant and fellowship support from the University of California. In 1916, he secured his first curatorial appointment—Assistant Curator of Mexican and South American Anthropology at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago—where he worked with the extensive American Indian collections for seven years before moving, in 1924, to the American Museum of Natural History in New York as the Curator of Mexican Archaeology. He remained there only briefly, and following an offer from the Penn Museum for the position of Curator of the American Section, he moved to Philadelphia in 1926. He was to remain at the Penn Museum as Curator until his official retirement in 1955. During his career from 1917 to 1955, he was in the field 16 times, working in archaeology, cultural anthropology, and linguistics. His most well-known archaeological fieldwork was conducted at two Precolumbian sites—Piedras Negras in Guatemala and Sitio Conte in Panama. He excavated Piedras Negras with Linton Satterthwaite, his graduate student assistant, who succeeded him as Curator in 1955.

Piedras Negras

Piedras Negras is a large Maya city located in the dense jungle in a remote part of northwestern Guatemala, near the Usumacinta River. Occupied since the 7th century BCE, it reached its height as an independent city-state during the Late Classic Period, the second half of the 8th century CE. The site was initially discovered, explored, and photographed by the Austrian Teoberto Maler from 1895 to 1899. In 1930, Mason visited the site as a prelude to further excavations and obtained permission from the Guatemalan government to remove one-half of the excavated monumental sculptures to the Penn Museum on long-term loan and ship the other half to the museum in Guatemala City.

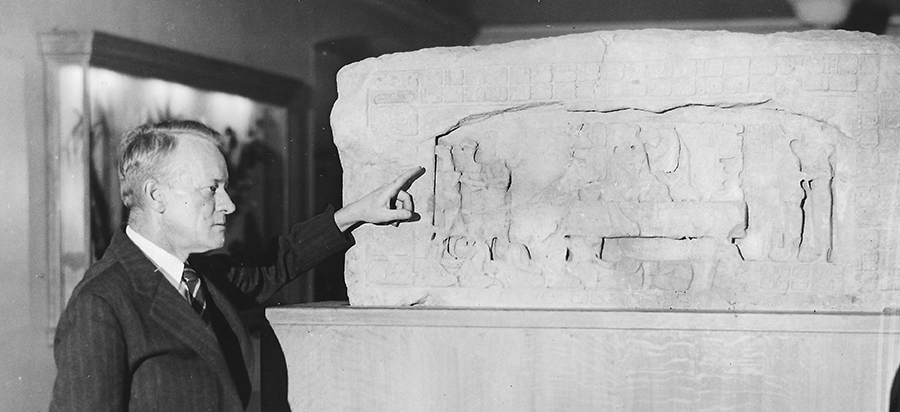

The excavation was difficult: Mason had never worked in a rainforest, and it took two seasons to construct a road to the site and transport the massive stone works including stelae. The second season of excavation resulted in new mapping of the site, but a fire occurred in the camp which destroyed many records including valuable photographs. Stela 14, brought back to the Penn Museum by Mason and still on display in the Mexico and Central America Gallery, was instrumental in the translation of Maya hieroglyphics by the famed epigrapher Tatiana Proskouriakoff. Inspired by her work as a volunteer at the Penn Museum, Mason and Satterthwaite invited Proskouriakoff to sketch the monumental Maya buildings and sculpture at Piedras Negras. She later used Stela 14 to show, for the first time, that Maya glyphs described historical events in the lives of ordinary people as well as royalty, and were not just calendrical and astronomical information.

Sitio Conte and the River of Gold

The story of Sitio Conte and J. Alden Mason reads like a script for a famous Hollywood movie. In the early 1900s, rumors spread of children playing marbles with gold beads near the Rio Grande de Coclé, a river in Central Panama. Later, in the 1920s, many finely made gold objects including jewelry and other ornaments became available for sale in the shops and markets of Panama City. Word of the discovery of gold artifacts spread. Due to the river changing its course and objects washing out of its banks, the site of a large Precolumbian cemetery was revealed, creating the impression of a River of Gold (the name of the Penn Museum exhibition that opened in 1988).

After initial work at Sitio Conte by Harvard’s Peabody Museum in the early 1930s, the Penn Museum, under Mason’s direction, conducted an excavation at the site in 1940. This was on private land owned by Señor Miguel Conte, in the Province of Coclé, approximately 10 miles from the Pacific Ocean. The work was carried out by Mason and his collaborators from January to mid-April. During their excavation, several burials with skeletal remains were discovered. However, one multi-grave burial yielded an amazing quantity of grave goods, including large numbers of gold artifacts that had been placed around the principal occupant of the burial, evidently an individual of high status. By the close of the expedition, over 120 troy ounces of gold were found including exquisite repoussé plaques and other ornaments. More than 6,600 pounds of stone artifacts and pottery were also excavated. Various aspects of the excavation were recorded on film. Hundreds of artifacts associated with the Coclé people at Sitio Conte were recently on display at the Penn Museum in a special exhibition, Beneath the Surface: Life, Death, and Gold in Ancient Panama (see Expedition 56.3:16-25).

Curator Emeritus

Following his “official” retirement in 1955, Mason was appointed Curator Emeritus at the Museum. By this time, he had conducted extensive fieldwork in the U.S., Mexico, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Panama, and Guatemala. However, Mason did not retire. The next dozen years of his life were spent working actively in anthropology. In 1952, Pelican Books asked him to author a book entitled The Ancient Civilizations of Peru, which was published in 1957. I have a prized copy of the book, given to me and signed while I was studying with Mason. He became associated with the New World Archaeological Foundation as an editor and archaeological advisor after a trip to Chiapas, Mexico in 1958. Mason continued to remain academically productive, writing numerous articles and chapters in diverse areas of anthropology. He continued to come to his office at the Penn Museum where, fortunately for me, his natural curiosity was piqued by a youngster with a dilapidated notebook making sketches of Stela 14, which had, by then, resided in the Museum for decades.

A Mentor for Young Anthropologists

It has been said that I am, perhaps, one of the few living persons who has worked with J. Alden Mason. This is not due to any supernatural longevity on my part. Rather, it is the consequence of my having known him since I was a boy and, later, a young man at the Penn Museum (then The University Museum) during the 1960s. The story of my multi-year association with Dr. Mason as a young protégé may be unique. Growing up in the working-class city neighborhoods of Philadelphia, I wanted nothing more than to become an anthropologist. I visited The University Museum every chance that I had, skipping school and going there several days each week. I haunted the galleries, copied and translated hieroglyphs, drew the exhibits, and attempted reading archaeology journals and texts that were too advanced for my limited pre-collegiate understanding.

One day, while returning to his office in the American Section, Mason observed me busily sketching Maya Stela 14. He was curious about my activities and leafed through the pages of my notebook, which contained hundreds of my drawings and tracings. He invited me to his office and began a discussion with me about his work in archaeology. Thus began my long association with “The Chief” (as Mason was often called), which was to last until his death in November 1967. Although I did not realize it at the time, the man who was to become an important figure in my life was, arguably, one of the greatest of his generation of anthropologists. Thanks to my time spent with J. Alden Mason, I had the opportunity to meet with such luminaries in anthropology as Penn Museum anthropologists Carleton S. Coon (a regular guest on the pioneering 1950s television program What in the World?), Froelich Rainey (Penn Museum Director and arctic archaeologist), Loren Eiseley (famed author and anthropologist), and the Chief’s close friend, former graduate student, colleague in the American Section, and co-excavator at Piedras Negras, Linton Satterthwaite.

Although my friendship with Mason did not begin until the early 1960s, I understood that he was highly respected as a dedicated, kindly, and generous teacher who enjoyed mentoring young students of anthropology, as he did with me. My working with J. Alden Mason has affected the entirety of my professional career, as well as my continuing relationship with the Penn Museum. When he passed away 50 years ago on November 7, 1967, the world lost not only one of its most beloved scholars, but also one of the last of the small group of renaissance anthropologists of the 20th century.

Understanding Maya Inscriptions

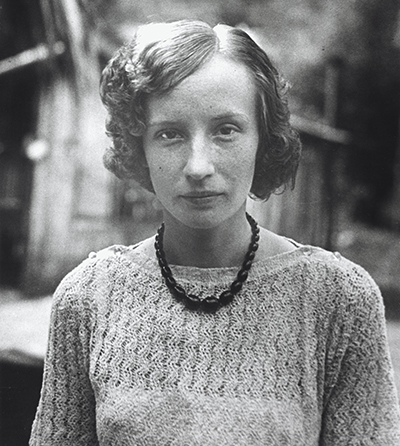

Stela 14 from Piedras Negras was used by Penn Mayanist Tatiana Proskouriakoff to prove that Maya inscriptions recorded real historical events, not just calendrical information as had been previously thought. Proskouriakoff began her study of the stela when she worked with J. Alden Mason and Linton Satterthwaite at Piedras Negras in 1936–7. She published the final results of her work in 1960.

At the time, scholars could read the Maya number system and understood how their calendar worked, but the syllabary—which allows us to read ancient Maya language—had not yet been deciphered. Proskouriakoff noticed patterns in the dates on stelae from Piedras Negras that suggested they referred to the births, deaths, and accessions of seven rulers in a dynasty that lasted 200 years. This important breakthrough enabled the reconstruction of dynasties at other Maya sites as well, significantly expanding our knowledge of Maya political history.

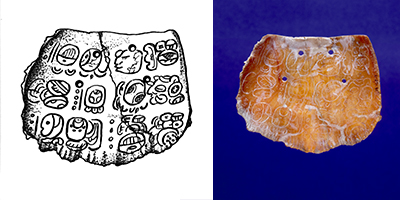

Stela 14: Hidden Secrets Revealed

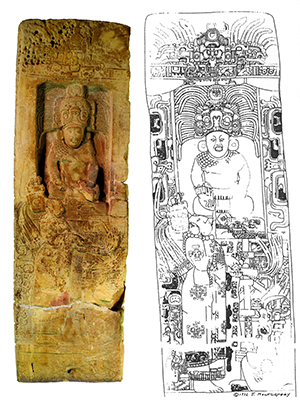

Stela 14 was found in front of one of the main temples of the city. It is a typical Classic Maya limestone monument, with a scene carved on the front and hieroglyphic texts on both its sides.

[1] The King

Seated ruler of Piedras Negras, Yo’nal Ahk III, who reigned from 729–757 CE. He wears a headdress that includes parts of his name in pictorial and hieroglyphic form.

[2] Bird Deity

This element represents the head and splayed wings of the Principal Bird Deity, the supreme god of the sky.

[3] Sky-Band

This horizontal band represents the heavens, containing a string of emblems for the sun, moon, and stars.

[4] The Mother

This woman is the mother of the king. She wears an embroidered dress and a headdress featuring a human skull.

Penn Museum objects from Piedras Negras have been on loan from the Guatemalan government since the 1930s.

David A. Schwartz, M.D.is a Clinical Professor at the Medical College of Georgia and also a Medical Anthropologist. His friendship with J. Alden Mason led him to major in anthropology/archaeology in college. A longstanding friend of the Penn Museum, Dave was named to the Museum’s Board of Overseers in 2016.

For Further Reading

Mason, J.A. The Ancient Civilizations of Peru. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964 (1957).

Proskouriakoff, T. An Album of Maya Architecture. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2003.

Rainey, F. Reflections of a Digger. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1992.

Solomon, C. Tatiana Proskouriakoff: Interpreting the Ancient Maya. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.