In December 1948, John Franklin Daniel III and Rodney S. Young surveyed the site of Gordion, one of the fabled cities of antiquity. Little did either of them know that this would become the Penn Museum’s largest and longest excavation.

The year before, Froelich G. Rainey had been appointed Director of the Penn Museum, and immediately set about expanding the Museum’s field research program, which had been interrupted during WWII. The Museum was already digging in the Mediterranean at Kourion, Cyprus, under George McFadden, but Rainey and Daniel, the Museum’s young Curator of the Mediterranean Section, wanted to explore older sites.

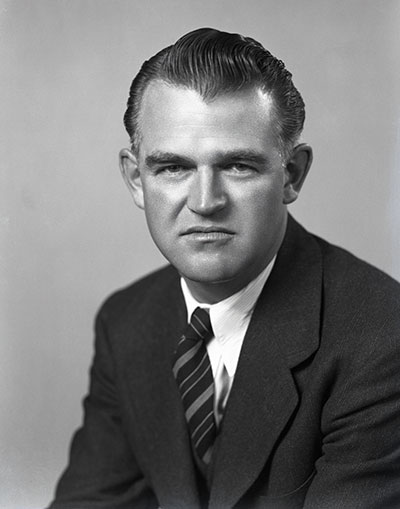

Daniel began working in archaeology at Kourion in 1934. He studied in France, Germany, and Greece, before obtaining a Ph.D. in Greek from the University of Pennsylvania in 1941. He joined the staff of the Museum in 1940, but took leave in 1942 to join the Greek Section of the Office of Strategic Services (see Susan Heuck Allen, this issue). By 1947, he was both Curator of the Mediterranean Section and Professor of Classical Archaeology. In 1946 he had also become editor- in-chief of the American Journal of Archaeology. Daniel specialized in the study of Mycenaean culture and the Cypro-Minoan Script.

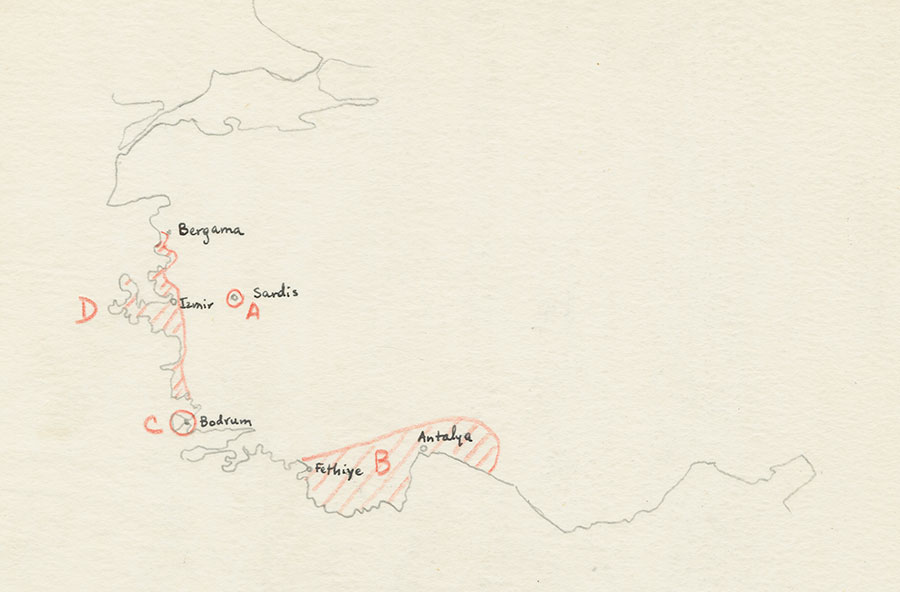

Turkey, with thousands of sites, was full of archaeological potential. At first, Daniel wanted to dig at Sardis, the ancient capital of Lydia, in western Turkey, or at other sites along the western and southwestern coasts of Turkey, including the areas around Bodrum and Antalya. Daniel and Young surveyed these regions in the fall of 1948, and planned to begin digging in 1949. The project was to last at least five years.

By June 1948, having not heard back from Turkish officials, Daniel considered abandoning the project and looking to Greece instead. However, permission finally arrived, and Turkey beckoned once again. Daniel traveled to Cyprus in September to continue work at Kourion, and was joined by Rodney Young in Ankara on December 2, to meet Dr. Hamit Koşay, the Director of the Department of Antiquities and Museums in the Ministry of Culture. This meeting changed their plan. Daniel wrote to Rainey on December 5:

Our Christmas present to the Museum is a totally satisfactory report on progress here. Our reception has been rather overwhelming, and everything possible has been done to make us feel welcome. Archaeologically this has been shown in considerable generosity in sites. We can apparently have any site we want, even the really major sites which were formerly reserved for the Turkish service are available. Most of the nice modest sites we were thinking of before have been lost in the rush, and we are thinking of bigger and better things. At present the betting is that we will settle on Gordion, which I have always considered one of the most important of all ancient sites.

Daniel and Young visited the site, even though covered in snow, on December 7, 1948. Daniel noted:

[w]e saw some very good walls not mentioned in their [Gustav and Alfred Körte, who had excavated at Gordion in 1900] report, and, also not mentioned in their report, a very deep burned level. Whether this belongs to the destruction by the Cimmerians or some other invasion remains to be seen. It is likely to mean objects reasonably well preserved and a useful chronological point: possibly a very useful one.

Daniel was ecstatic about the site upon his return to Ankara:

Rodney, who is less given to superlatives than I, calls it magnificent. I am in a general state of unbridled enthusiasm…the site is practically untouched and is not inhabited…It has good water (a spring) and some supplies. It is on the Ankara-Istanbul railway. The only drawbacks were that they would need to build a house and that the nearby swamps were malarial.

Daniel wrote:

We spent the whole morning in going over the site, and were so impressed with its possibilities that we were almost ready to decide for it on the spot.

Even so, on December 9, Daniel and Young proceeded to Istanbul to pick up a jeep sent over from the United States, to continue the original survey. ey were joined by G. Roger Edwards, a student at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, whom Young had met recently (Edwards later joined the Mediterranean Section of the Museum, 1950–1985).

Tragedy, however, then befell the expedition. On December 17, while driving back from the site of Korkuteli, near Antalya, on the southwest coast of Turkey, Daniel fell ill in the jeep, and died before any help could be obtained. He was pronounced dead from a heart attack at the hospital in Antalya.

John Franklin Daniel was buried in the Greek Cemetery at Episkopi, Cyprus, near the ruins of Kourion where he had worked for many years.The entire village turned out for the funeral. Daniel, who was extremely well-liked in Cyprus, was eulogized in a local magazine: The waves of the best coast of Cyprus will surround his grave with infinite love.

The Museum was shocked by Daniel’s death. In the ensuing years, Rodney Young proved an extremely able successor, and assumed leadership over the excavations at Gordion. But the loss of this scholar, only 38 years old, was deeply felt. In a 1948 obituary, the American Journal of Archaeology (52:4) wrote:

He was at the height of his powers and full of enthusiasm for his projected work when the end came. In his passing the archaeological world has lost one of its most promising and richly gifted young scholars, one from whom much more was to be expected. Some consolation for the loss is afforded by the fact that his last days were extremely happy ones.