BEFORE DR. ROBERT H. DYSON, JR. became Williams Director of the Penn Museum in 1981, he established himself as an archaeologist working in the Near East. This story takes us back to 1951, when Dyson was a graduate student in anthropology at Harvard University. He traveled to the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa with the Marshall family, to study remote African peoples.

U.S. Scientists to Film South-West Bushmen in Natural Surroundings.

This was the headline of the 1951 Windhoek Advertiser article heralding a series of expeditions undertaken by the Marshall family of Cambridge, Massachusetts, to the Kalahari Desert. Upon retirement, Laurence Marshall, a founder of Raytheon Industries, was determined to create a constructive family project. Neither he nor his wife Lorna, an English teacher, had training in anthropology or film, but they—and their teenage children, John and Elizabeth— decided to find and extensively document a group of hunter-gatherers who were untouched by modernity.

Despite forming an affiliation with the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, the Marshalls were unable to find a professional anthropologist to accompany them. At the time, both the Peabody and Harvard’s anthropology department were more focused on Native North and South Americans; the indigenous peoples of Africa were more commonly studied by European scholars because of their colonization of the continent. In the absence of an available Africanist, the Marshalls enlisted a promising young Harvard graduate student: Robert (Bob) H. Dyson, Jr.

Dyson was widely considered to be one of the anthropology department’s best graduate students and was already a member of Harvard’s exclusive Society of Fellows. He had enrolled at Harvard as an older undergraduate, after serving in the Navy during World War II. He had accompanied Peabody Museum Director J. Otis Brew for two seasons to study the Awatovi Ruins in the American Southwest and had conducted fieldwork on prehistoric sites in Maine and New Brunswick (Canada).

Negotiating the Kalahari

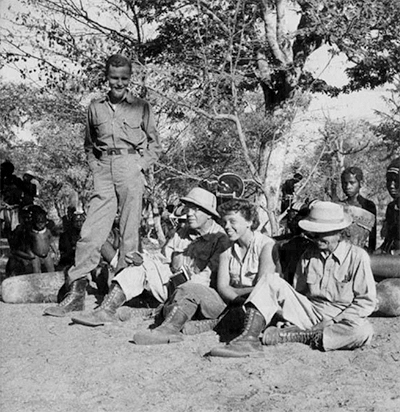

Bob Dyson and Laurence Marshall arrived in southern Africa in May 1951—a month before the rest of the expedition—to do reconnaissance and determine exactly where they would seek unacculturated people. Based on various consultations with academics and prospectors, Marshall and Dyson decided “to work on a Bushman group” near the waterhole known as Gautscha Pan, located at roughly 20° S, 20° E in Southwest Africa (now Namibia). Bushman—a term later deemed pejorative— referred at the time to a number of southern African peoples, including the Ju/’hoansi, with whom the Marshalls and Dyson ultimately worked.

In addition to helping with logistics and guiding the Marshalls in research methodology, Dyson was tasked with posting regular reports on the expedition’s activities for Peabody Museum Director Brew. The missives, which are the most thorough documentation of the expedition, are professional—covering details from archaeology, of which there were few useful artifacts, to filming and still photography, to logistics. Above all, they also reveal that Dyson had a wry sense of humor.

In his first report, he described the difficult journey to southern Africa: “Started in Rome. Had breakfast at Kano in Nigeria, lunch in the Hotel at Brazzaville (Fr. EQ.AF.) overlooking the Congo; dinner somewhere over the Kalahari Desert, and bed in Jo’burg.” Ultimately, in addition to Dyson and the Marshalls, the large and ethnically diverse expedition included local scholars, a government official, and a staff of mechanics, interpreters, and cooks. After loading up with petrol drums, medicines, spare auto parts, water, and food, the team (which Dyson likened to a “stampede”) caravanned out of Windhoek in “the Dodge, the Chuck Wagon, and the Hotel. (The latter having luggage compartments and sleeping decks).” Angling over heavy sand dunes, plowing through tangled scrub, their radiators boiling over, five huge trucks made their way past brush fires and steep cliffs “through the wildest remaining Bushman country.” “Little game and no water. Backs all sore from constant jouncing up and down. Lead Dodge fell into a hole,” Dyson groaned. Under these conditions, the expedition had fewer than six weeks to find Bushmen, explain their purpose, negotiate a working relationship, get to know individuals, and observe and document their customs.

Studying the Ju/’hoansi

It took them two full weeks to reach the isolated Nyae Nyae area in the western Kalahari. In its center, was a circle of 13 water pans (flat expanses of ground that contain water), where animals and people grouped during the annual dry season. In the middle of that, was Gautscha Pan. There they set up camp among jackals, vultures, guinea fowl, wildebeests, kudu, lions, snakes, and scorpions. It was four anxious days before they had a glimpse of Ju/’hoansi. Lorna Marshall described the first meeting in her 1951 diary:

We walked back in the noon heat along the edge of the pan. The heat was crushing. We sat down in the shade with a cup of tea and chatted a little while. Suddenly Bob [Dyson] looked up and there sitting in a circle 60 feet from us were 7 Bushmen. Our two guards and five others. We had not seen or heard them come. I am very excited and happy. Bob gave them tobacco… (July 3, 1951)

After introductions, the expedition team persuaded the Ju/’hoansi to move their families closer to Gautscha Pan where the team could better observe their daily activities. Lorna recorded the Marshalls’ response:

Mr. [Claude] McIntyre [soon to be commissioner of Bushman Affairs, S.W.A.] and Bob [Dyson], with Picanin interpreting, had a conference this morning with the Bushmen about the plans. They were asked to bring all their belongings. Bob explained the reason as follows. He said that at home there was a very big house [Harvard’s Peabody Museum]. Each people had a room in it, with all their things in it to show the way they lived. The English had a room. The Bantus had a room and so on. Bob thought that they seemed pleased to think Bushmen would have a room, too. Bob said that we had nothing yet to put in it and that was why we were asking them to make things for us. (July 8, 1951)

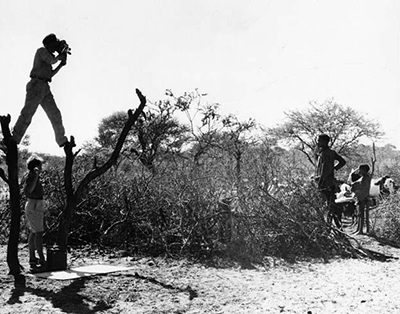

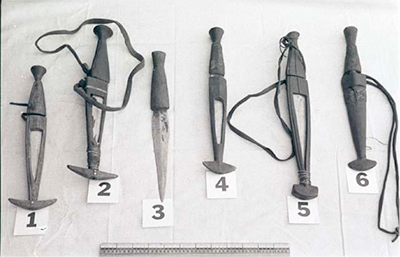

As Dyson reported to Brew, “To begin our work here we had them all load up (the trucks) with their belongings and move to a new place where they set up a new werft [homestead] including fire making, etc., etc.” Once the Ju/’hoansi families arrived, the camp bustled with activity. Lorna Marshall spent her time observing women and children and recording names for kinship charts. Elizabeth shared modeling clay, paint, and crayons with the children, recording the results. Laurence occupied himself with the expedition management while Dyson and John Marshall concentrated on filming “most of the important aspects of both technology and culture” such as “playing, misc. activities, making the bow, arrow, shell beads, working skins, cutting up meat, building skerms [temporary dwellings], making fire, using digging sticks, cooking, making their axe-adze, collecting and applying poison, hunting (staged however), collecting water, eating, making metal arrow points, making dance rattles and so on.”

From the outset, the expedition’s work was fruitful. “In general we had a marvelous time, getting to know each Bushman as a personal friend,” wrote Dyson without a trace of irony. “They soon understood the language difficulty and overcame it very easily by pantomime. The language is not so difficult as one might think. They only use four clicks but vary the tones.”

Although at the time it was not unusual in southern Africa to force anthropological subjects to cooperate, the Marshalls instead distributed food, coffee, sugar, salt, and tobacco to the Ju/’hoansi they photographed and interviewed that year. In order to keep up with the demand for meat, the expedition was compelled to shoot more game than their permits allowed. In addition, said Dyson “we badly calculated our own supplies and fell short of sugar, coffee, and mealie meal before we were finished… The moment they got hungry they simply became noncooperative.”

As Dyson commented, “The whole thing was done with express train rapidity and it is astounding that we covered what we did in the time.” This included a nascent kinship study, information about inheritance of the headman’s position, film footage of a curing ceremony, numerous pictures of artifacts and people, and records of body measurements. They interrogated the Ju/’hoansi to compare what they learned with earlier records. As Dyson said “There were a few deviations (for example God’s two story house now has a corrugated tin roof, and God himself has obtained a pair of white trousers!)” This, he surmised, “probably comes from the missionary work among the Bechuana with whom these people trade.”

Nevertheless, the team did not collect many artifacts because they did not have “sufficient goods” for trading, as “for objects in use, like mortars and pestles, one must be able to replace them with equal equipment and this we could not do.” They found, though, in and around most of the water holes they visited, evidence of Late Stone Age sites, with implements such as blades, as well as more recent potsherds and some European glass beads.

Much to the dismay of Dyson and the Marshalls, local officials suddenly cut short the Nyae Nyae stay from six weeks to less than a full month. As they left, the Marshalls handed out presents to all involved.

Before returning to the United States, the Marshalls, along with Dyson, attempted to do comparative research on other African peoples in nearby Angola, but rampant brush fires and rain-swollen rivers made travel difficult. Undaunted, they began to plan a longer trip for the following year. Even in 1951, it was clear that the Ju/’hoansi’s lives were about to change significantly—beyond whatever might be due to their incursion. Moreover, there was talk of opening up the land to farmers and putting the hunter-gatherers on a reservation, something that eventually happened in 1960.

Future Expeditions

Ultimately, the Marshall family went on to conduct six more expeditions to Nyae Nyae before 1961, with the various Marshalls returning at different points into the 21st century. They produced over 24 ethnographic films, several anthropological books and articles, and some 40,000 photographs. The results were a comprehensive study of the Ju/’hoansi, which countered prevalent negative stereotypes of the Bushman, revitalized academic interest in Bushmen, and charted new pathways in anthropological fieldwork, ethnographic film, and documentary photography that have relevance to this day.

Bob Dyson never returned to Nyae Nyae and there is no evidence that he published about the Kalahari journey. Dyson went on to a distinguished career as an archaeologist and, after participating in the Jericho excavations, directed the Hasanlu (Iran) excavation project from 1956–74. He served as Williams Director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology from 1981 to 1994.

Ilisa Barbashis Curator of Visual Anthropology at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Her book on the Marshall Family Photo Collection, titled Where the Roads All End: Photography and Anthropology in the Kalahari, will be published in 2017 by Peabody Museum Press.

This article refers to the following materials at the Peabody

Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology:

Expeditions Photographic Catalogs, 2001.29, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

Lorna Jean Marshall, LJM Diary 1951, Peabody Museum. 51-60-50/13156.1.1.

#51-60, South-West Africa Expedition Records, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

A link to John Marshall’s films can be found at: http://www.der.org/films/kung-series.html

Except where otherwise noted all images in this article are Gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

All Robert Dyson quotes are courtesy of South West Africa Expedition Records (#51-60), Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.