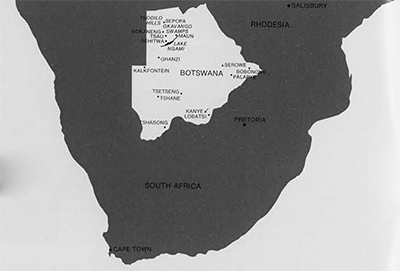

Except in relation to the surrounding countries of the Republic of South Africa, Rhodesia and South West Africa, the Republic of Botswana (ex Bechuanaland Protectorate) rarely makes the headlines. The greatest part of the country is occupied by the Kalahari Desert, a desolate expanse but for the fringing areas in the north where they border the permanent waters of the Okavango inland delta inhabited by a population of 50,000 and their cattle. The bulk of Botswana’s population of around 600,000, however, inhabits a strip of rolling country on both sides of the “line,” i.e. the railway from Cape Town in South Africa to Salisbury in Rhodesia, which runs parallel with its eastern border for several hundred miles. Occupation of this narrow strip is not entirely due to easy access to the railway, although it certainly boosts business, but also to the fact that this part of the country has a far higher rainfall than the rest of Botswana, mostly waterless sand, shrub and stone. It is here, in this wasteland, objectionable to the Bantu, undesired by the white man, that the Bushmen live. Expelled from previous vast areas in eastern Africa by the Bantu’s southward thrust, confined by the expansion of European-held peripheral regions, the Bushmen, the last of the African hunter-gatherers, have managed to survive in small groups in an environment which must be at the limit of man’s adaptability.

Except in relation to the surrounding countries of the Republic of South Africa, Rhodesia and South West Africa, the Republic of Botswana (ex Bechuanaland Protectorate) rarely makes the headlines. The greatest part of the country is occupied by the Kalahari Desert, a desolate expanse but for the fringing areas in the north where they border the permanent waters of the Okavango inland delta inhabited by a population of 50,000 and their cattle. The bulk of Botswana’s population of around 600,000, however, inhabits a strip of rolling country on both sides of the “line,” i.e. the railway from Cape Town in South Africa to Salisbury in Rhodesia, which runs parallel with its eastern border for several hundred miles. Occupation of this narrow strip is not entirely due to easy access to the railway, although it certainly boosts business, but also to the fact that this part of the country has a far higher rainfall than the rest of Botswana, mostly waterless sand, shrub and stone. It is here, in this wasteland, objectionable to the Bantu, undesired by the white man, that the Bushmen live. Expelled from previous vast areas in eastern Africa by the Bantu’s southward thrust, confined by the expansion of European-held peripheral regions, the Bushmen, the last of the African hunter-gatherers, have managed to survive in small groups in an environment which must be at the limit of man’s adaptability.

The Kalahari can be divided into three types: regions of typical sand dunes in the south and the west, the mixed shrub, grassland and occasional Acacia woodland in the center, and the vast shallow depression in the north, some 6,500 square miles in extent, in which the Okavango River disappears, with out issue, in a maze of channels and swamps. More than half of the river’s yearly inflow evaporates in this inland delta, leaving only a trickle to decant into secondary evaporation pans, such as Lake N’gami and the Makarikari and Lake Dow depressions.

My wife and I had the good fortune to travel extensively in these regions during my two years’ research on tsetse flies and sleeping sickness. During one of our trips we traversed the central Kalahari from Lobatsi to Ghanzi and from there up north as far as the Tsodilo Hills and back to Maun, our place of residence during those two years. The first 500 miles involved some rough going when our LandRover had to fight its own way through deep sand, the normal tracks which marked the “road” having been cut by lorries with a wider wheelbase. The adventure was further spiced by an anxious morning of carburetor trouble, bringing before our eyes the specter of a slow death by dessication after our small water reserves gave out. Monaletsatse, our Tawana driver, had already given up hope when the cause of the breakdown was found to be simply a grain of sand preventing the proper function of one of the jets that regulate the inflow of petrol at the entrance of the carburetor. After that we had no further mechanical trouble. Our progress was sluggish, however, and rather unpleasant as the LandRover was continuously thrown from one side of the wide track to the other, the heat build-up inside the slow moving vehicle in the wind- and shadowless desert was intense, and even in places where the going was good we made several stops when Dora spotted “new” flowers for her botanical collection.

The central Kalahari region is described as a featureless, gently undulating, sand-covered plain at an elevation of 3,000 to 3,600 feet above sea-level, with maximum elevation in the east, near Kanye, at about 4,000 feet. The desert is essentially a layer of sand, from 300 to 600 feet thick, laid down since pre-Pleistocene times on top of solid basalt bedrock. Aeolian Kalahari sand deposits extend from fairly far south in South Africa up into the Congo basin. Striking topographic features of the central Kalahari are the sudden narrow dry valleys, locally called mokgacha. These are fossil river beds, remnants of important drainage lines which have undergone repeated cycles of pluvial and non-pluvial periods. One of the best marked of these valleys is that of the Okwa “River,” the dry bed of which can be traced from well inside South West Africa to close to Lake Dow into which it probably drained during pre-historical pluvial periods.

It was during the early morning of the third day that we saw our first Bushmen, a couple of young boys herding a flock of sheep. Early mornings in the Kalahari at that time of the year (early September) are bitterly cold and they were shivering in spite of the blanket around their shoulders. During the same morning we came to a large dry pan of glaring white limestone. There is some speculation about the origin of the “pans.? One theory has it that they are formed by trampling of game coming to drink periodically at hollows containing water. Over the centuries soil around the hollow would be removed by ingestion during drinking, and carried away with the hoofs. Another theory is that of the undermining of an area with numerous burrows made by rodents and further enlarged by wind action. The pans are ecologically very important as through their distribution in the Kalahari areas they govern game migration which, in turn, plays a large part in the survival and nomadic life of the Bushmen.

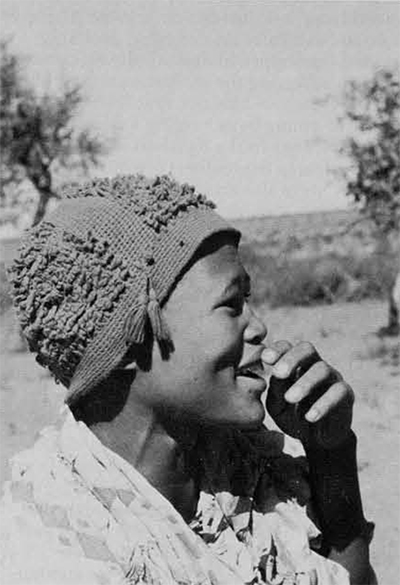

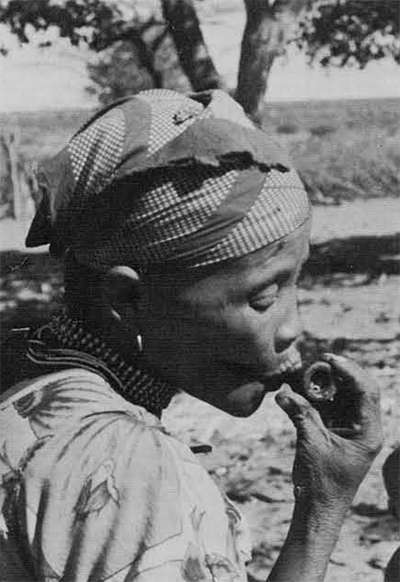

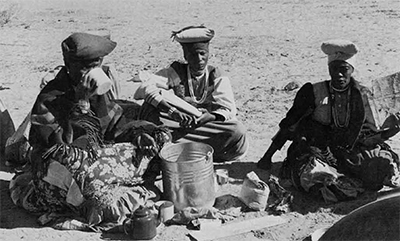

At a borehole, near Ghanzi, we encountered a band of Bushmen of two or three families. We spent some time trying to communicate with them, without too much success, except for a lively exchange of smiles. One of the women had a very striking “primitive” neanderthal-type head with very pronounced brow rims. Two of the women had small babies. One of the babies showed the typical peppercorn hair pattern, so characteristic of the Bushman people.

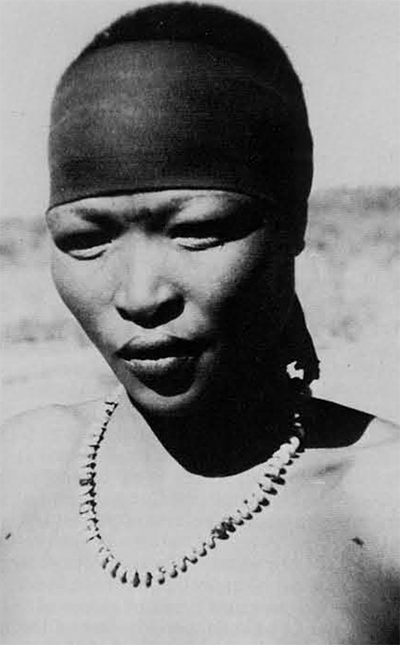

Like other few remaining primitive hunter-gatherers groups, the Bushmen have become the subject of urgent anthropological studies, before their culture and genetic characteristics are absorbed by acculturation and intermarriage with other ethnic groups. The Bushmen share very few characters with the Bantu or other people who inhabit Africa. They are small in stature (average under 5 feet), the color of the skin is light yellowish-brown, the outline of the face is rather triangular with a flat-topped head, a low forehead often showing two frontal bosses. The narrow, slanted eyes and the prominent cheekbones, together with the yellow skin lend a very marked mongoloid character. The hair on the head is implanted in a regular pattern, called “peppercorn.” Unique is steatopygia, a fatty accumulation in the buttocks and thighs of the otherwise non-obese women. This accumulation of “fat tissue” is especially marked in mature and old women and also in some old men. In women, this outstanding (literally!) feature is enhanced by a hollowing of the back at an early age. Thus steatopygia is the result of both postural and humoral modifications. It increases in the female with language shared with a few other South African groups. The “clicks” are produced by pressing the tongue against the roof of the mouth or the teeth. There are at least three different kinds of “clicks,” each conveying a different meaning to the word.

The number of Bushmen in Botswana was estimated at about 24,000 during the 1964 census. Only about 6,000 of these are living full time in the traditional way of hunter-gatherers. The rest live in different degrees of acculturation in close contact with Bantu villages or cattle posts, while 4,000 are permanently employed at ranches in the Ghanzi area.

To arrive at Ghanzi, Kalahari’s metropolis, at high noon is like driving into the center of a huge concave mirror turned towards the sun. The post lies in a depression of glaring white limestone while the sun rays and heat also bounce back from every single plant and object coated during hundreds of rainless days with a thick layer of limestone dust. If it wasn’t for the heat one could imagine himself in mid-winter in the northern hemisphere. Ghanzi boasts a Post Office, a petrol station, a general store and the District Commissioner’s Office combining police, prison and radio station. It is the center of vast farmlands, somehow won from sparse patches of fertile soil and kept under produc tion in spite of uncertain rainfall, uncontrollable seepage water, devastating goats and unreliable labor. Cattle are struggling for survival and only the horses seem to do well.

We filled our petrol tanks and reserve cans, and our four jerry cans with water, after which we were glad to leave the oppressive white glare. Psychologically, the worst of the Kalahari appears to be over once one is north of Ghanzi. It is from here, however, that the road dissolves in a winding track of volcanic rock and limestone, alternating with patches of deep sand made particularly bumpy by uncovered roots and unyielding stone ridges in the center. During the first part we had to stop innumerable times to open and close the gates of the barriers by which each pasture is fenced off.

We started meeting Herero horsemen as we were now nearing Sehitwa, their main village in Botswana, on the northern shore of Lake N’gami. From high up on their horses they looked down upon our dusty, safari-battered LandRover, with the supercilious grin of veteran Kalahari travellers towards greenhorns. And Monaletsatse’s grimy hat did nothing to diminish the contempt in their lordly stare.

At one point the road splits into two branches, with no indications. Monaletsatse stated that the one on the right was shorter but, depending on the level of the lake, could lead to a muddy death. We took the one on the left. From a distance Lake N’gami looked indeed like a huge mud pool, a far cry from the last century romantic descriptions of Livingstone, Andersson and Baines, who saw the lake when it was still receiving the yearly flood waters from the Taoghe River, up north. At the present this river seldom runs nearer than fifty miles north of the lake. During most years the inflow into the lake comes from the irregular and seasonal run of the Ngabe River in the east, itself dependent upon the amount of water drained by the Tamalakhane and Botletle Rivers. It all sounds complicated and it is.

Sehitwa is a large and interesting village spread over several miles of thicket and tree savannah bordering the shores of Lake N’gami. It was the main rallying point for migrating Herero and their cattle and has remained to this day the largest Herero community in Botswana. They do not belong to a Botswana ethnic group but were accepted by the Tawana when they fled South West Africa after their defeat in an uprising against the German colonial forces at the beginning of this century.

We made camp in a quiet spot but had trouble keeping away stray cattle, children and flies. We left again early the next morning.

North of Sehitwa the country changes into large patches of lush grassland mixed with wood savannah in which Acacia giraffae (Camelthorn) is dominant in various stages of growth and densities. The very humpy track winds through the trees offering a large choice of detours and deviations, leaving it to the traveller to pick the most likable way amongst the potholes, dry at this time of the year, and the thousands of hoof prints. Rainfall in the central Kalahari is somewhere around 10 inches a year. Here it almost doubles that amount, most of it coming down in the first three months of the year, when stretches of this road turn into knee-deep pools.

Twenty-five miles north of Sehitwa one reaches the large village of Tsau, traditional and administrative capital of the Tawana people until 1925 when the capital was moved to Maun, 60 miles east. From here the track cuts through the fringing vegetation bordering the Okavango swamps, the kingdom of the beautiful sitatunga antelope, the red lechwe, the waterbuck, the hippo and the crocodile. The vervet monkey is everywhere and bands of baboons are common. The surrounding grassland is grazed by large herds of roan and sable antelopes, kudu, tsetsebe, zebra, blue wildebeest, reedbuck, steenbok, springbok, warthog and giraffe. Farther out, in the mopane forest, roam elephant, buffalo, Chobe bushbuck, eland, impala, gemsbok and duiker. Carnivores are numerous, including lion, leopard, cheetah, hunting dog, hyena and chackhal.

During the flood season from May to September, when Botswana simmers in the hot dry spell, the swamps receive the flow of the waters from the Okavango River that drained from the high plateaus in Angola six months previously. At the height of the floods, around August, peripheral dry river beds start filling up while outlying pans dry out, low-lying areas become lakes, and the Bushmen fall back on scattered springs and dig up their water-reserves stocked in ostrich shells in secret caches, lush grasses herald the advance of the floods whereas the vegetation inland withers and falls easy prey to bush fires.

The combination of dense vegetation, concentration of game and climatic conditions in and around the swamps provides ideal habitats for the tsetse fly, Glossina morsitans, the carrier of human and animal sleeping sickness (Trypanosomiasis). The presence of the disease has curtailed the full use of good grazing lands in the delta areas and is thus a serious drawback to the cattle industry, the main source of income of Botswana.

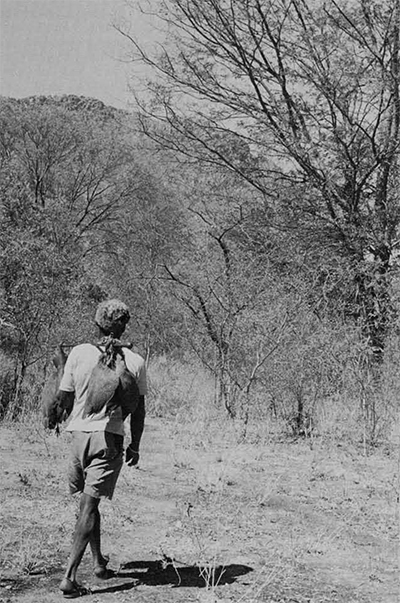

As one travels away from the swamps the vegetation changes into more open and stunted woodland with drought-resistant species becoming dominant. This transitional vegetation has a depth of 10 to 15 miles whence a typical Kalahari environment takes over. Tracks into this “wasteland” are rare and seldom used. One, starting at Nokaneng, an important village at the edge of the swamps, leads to some very interesting small settlements of mixed Herero and Bushman communities to end at Dobe, a Bushman village close to the South West African border.

We camped along this track on the first night after leaving Nokaneng. We had found a way to organize the LandRover so that we could sleep in it, but now, in the bitterly cold Kalahari winter nights, we almost froze to death. The next morning we found the tea left overnight to have turned into a solid block of ice. It took a good deal of shaking before the ice inside the jerry cans reached a semi-liquid state so that it could be poured out. Such is Africa! Monaletsatse said he had kept quite warm. No wonder, with a brisk campfire close to his camp bed and five blankets he had been thoughtful enough to take along. Nothing heats experience! Breaking camp was done with more enthusiasm than usually shown on warmer mornings. The track led across a series of ridges. These stand out very clearly on aerial photographs. They are regularly spaced at an average of about 3 miles from top to top, in a general southwest—northeast direction, covering an area just north of Tsau for about 100 miles until at Tsodilo Hills the “waves” seem to scatter. The origin of these fossil dunes, as they are called, is not known. Sixty five miles from Nokaneng we arrived at G//auche (the sign // indicates a “click”), a village of round mud-walled huts spread out on the sandy slopes of a ridge. It is a cattle post of Tawana and Yei, the cattle being herded by Bushmen. We were told that it sometimes happened that a cow or calf disappeared, taken by lions, the Bushmen reported. The Tawana or Yei owner has strong doubts about these disappearances but usually can not prove that lions are not the cause of his losses. Ten miles further on we arrived at XI/angwa, a mixed village of Herero and Bushmen. After 12 more miles we stopped at a group of temporary small beehive-shaped huts and were soon surrounded by a number of Bushman women. They belonged to the K//ung group, normally settled around the Dobe area close to the South West African border, only a few miles away. Dobe was the study area of two American anthropologists, some years back, and when we told them that Richard Lee, one of the anthropologists, was on his way back and was due to arrive in a few weeks, they were overjoyed. During his long solitary stay with them he had become, and was still considered, “one of the tribe.” They also knew, of course, that he would bring them many gifts from America, wherever that might be. The place did not offer much protection from wind, and no water being available close by we turned back and made camp at X//angwa. The following morning we once more found our reserve water frozen solid. We spent a most pleasant morning amongst the Bushmen, recording songs and making pictures. In the afternoon we moved our camp to G//auche. With our camp close to the water well we had the visit of Bushmen all afternoon. In the evening they came to sit at our campfire and although we could not understand a single word of what they said, and neither could Monaletsatse, it was fun to hear their clicking arguments. It was a wonderful balmy night, the sound of their voices and the dancing reflections of the fire on their baby faces will remain a lingering memory among the many unforgettable evenings at an African campfire.

The next day we left, back along the long, long track. In the early afternoon we reached the fringes of the Okavango vegetation and found our progress cut off by greedy grass fires and flaming acacia trees. Quickly we cut branches to beat out the flames along the track and dashed off before the fire could flare up again. So we proceeded from one patch to another until we finally came to the belt where all inflammable material had been consumed to a sort of primeval black landscape. We kept a wary eye for elephants whose fresh spoors were to be seen everywhere, indicating a stampede before the fires. We reached Nokaneng, hot and smudged with soot.

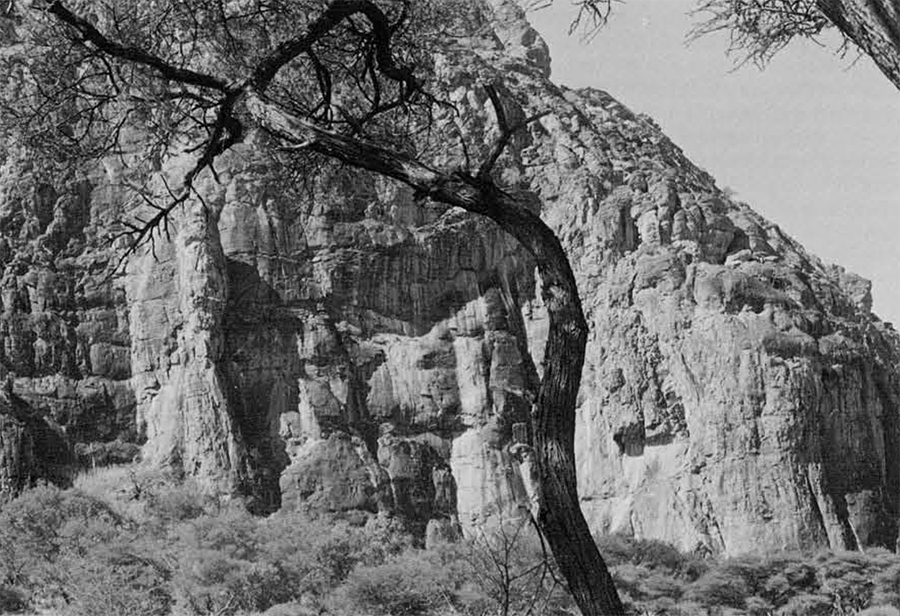

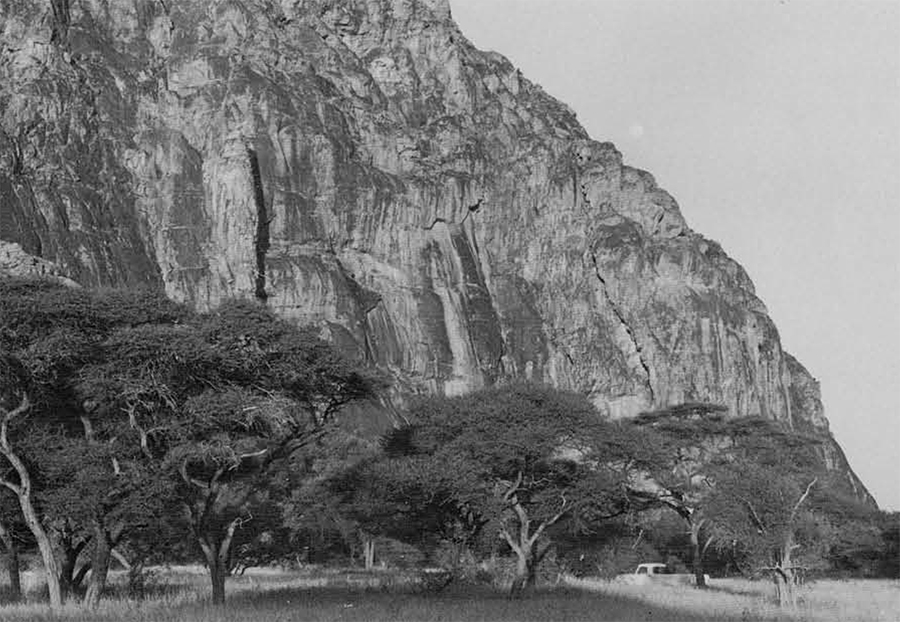

Nokaneng is inhabited mainly by Yei. It lies on the road along the western fringe of the Okavango delta which skirts the swamps and further north the Okavango River all the way to Mohembo at the border of the Caprivi Strip, and extends thence into Angola. At a point near Sepopa, another important Yei village some 70 miles north of Nokaneng, an alert and observant traveller will discover in the far and hazy distance a group of high sheer rocky peaks pinkishly shimmering in the late afternoon sun: solemn, silent and secret. Seven miles south of Sepopa, a well-marked turn-off leads to a less conspicuous sand track which becomes extremely bumpy with exposed roots as it winds through dwarf mopane (Colophosperm um =pane) and shrubby muselesele (Dichrostagys glomerata), the sharp thorns of the latter making a sorry sight of the LandRover’s paintwork. Once more can be seen the changing vegetation from dense Acacia giraffae of the fringes of the swamps into dry shrub and xerophytic trees and later into regularly spaced Burkea africanus and Lonchacarpus nelsii from about 25 miles west from the swamps. At this point the cone-shaped Tsodilo Hills stand out firmly and more beautiful than ever, dominating the desert landscape. Anxious to draw closer we did the few remaining miles at the high average speed of 30 miles an hour, oblivious of the rough track. It was late afternoon when we finally arrived at the foot of the sheer western wall of Tsodilo and we decided to camp right there with the full view of the perpendicular cliffs now strongly illuminated by the declining sun.

An island in the Kalahari Ocean, the Tsodilo Hills are a harbor to the wandering Bushmen. Here they will come in the latter half of the rainless season, sure to find water in several natural springs, hopeful in the presence of game and eagerly anticipating the e luxury of eating mogongo nuts from the tree Recinodendron rautenenii growing in profusion in the hills. During October and November the hills are the Cote d’Azur or the Palm Springs of the Kalahari when the desert has nothing to offer but sweat and tears. Proof that these seasonal migrations have gone on for perhaps many thousands of years is the presence of numerous rock-paintingssome of them said to date back to the Late Stone Age.

The Hills are composed of three distinct quartziferous masses and although rising to 1,200 feet above the surrounding plains, them- selves 3,200 feet above sea level, are ignored on many maps. They lie at 18°40′ South and 21°43′ East according to the 1961 Survey Department information. The southern and most impressive hill is a huge monolith in the shape of a gigantic half-submerged clam shell. For some reason, a few maps mark the three hills “male,” “female” and “Picanin.” The correct, Tawana name for the southern hills is Tsodilo which means “slippery” to describe the sleep flanks. “on which no one can stand.” The local Mbukush call it “Herumute” which means the same thing. A few years ago some goats belonging to Samuchoso, a Mbukush who lives not far away, walked into the “slippery hills” and liked it so much that they never came back. With a fine mountain-goat instinct they retreated to the most inaccessible places which Samuchoso could not reach. They are still there, no doubt starting a race of Capri tsodiloensis which will be of great confusion and interest to zoologists a few hundred years from now.

The central hill is called “Gumbiku” which is the Tawana translation of “millipede,” a fitting description of its very irregular, indented shape. The northern, lowest and smallest hill bears the name “Biengwa,” the meaning of which was not known.

The startling presence in an otherwise featureless expanse, the mute rock paintings, the crushing feeling of loneliness have made the hills a legendary place of mystery and the home of the “Spirits of Tsodilo Hills.” Awe and myth are expressed by author Van Der Post in one of the chapters of his book The Lost World of the Kalahari. Believing that the many adversities encountered during his filming safari to the hills resulted from the displeasure he had unwittingly caused the “Spirits,” he composed a letter of apologies, after consultation with his Bushman guide, in an effort to appease the “Spirits.” He enclosed the note in an empty lime-juice bottle which he left at the bottom of a cliff showing one of the nicest groups of Bushman paintings. In 1987, twelve years later, the bottle and the message were still there, with a number of messages other travelers had subsequently added.

That night, the “Spirits” put us to a severe test when cold and gusty wind squalls came screaming down the “slippery” mountain wall with hurricane force with the clear intention of blowing us, together with tent, bed and gear, well into the wide Kalahari. Several times did I have to get up to drive the pegs that held the top sheet deeper into the ground. My hammering, echoing back from the rock wall, must have sounded in fearful defiance of the “Spirits” to Monaletsatse and George, the cook, but neither stirred, pretending to be fast asleep. The next morning everything inside the tent was caked with what looked like volcanic dust. The wind had subsided, the fresh morning sun made the uncomfortable night seem unreal, and the “Spirits” smiled again.

One of the first white explorers to visit and describe the hills, and mention the rock paintings, was Passarge in 1893. As late as 1935, it took Andrew Wright, one of the N’gamiland pioneers, three months by oxcart to reach the hills from Maun, such were the conditions in that forsaken corner of the world during those times.

Someone had told us that there are 92 groups of rock paintings in the central (Gumbiku] hills. During our two days wanderings we saw most of them. The first group shown to us by Samuchoso, the self-appointed Mbukush guide, was in many ways the most exciting and one of the most difficult to reach at close quarters. We had to climb up boulders and squeeze through narrow passages between rocks to arrive finally at a kind of ledge. There we saw on the grey face of a flat cliff the ochre rufous outline of a giraffe, a kudu and a rhino and also, charming afterthought of the artist, the imprint of his or her small right hand. It is at the foot of this cliff, protected from the roving vervet monkeys by a few stones, that Van Der Post’s bottle is hidden. Inside the bottle we found his message now reduced to sodden strips of paper, and numerous later messages from persons who have visited the site since. I recognized the notes of two anthropologist friends and took the liberty to add my own remarks which ran something as this: “At this spot of unbelievable beauty and with a feeling of deep humility I am strongly aware of aeons of wisdom which made us what we are. As a parasitologist I am inclined to think that sleeping sickness and tsetse flies played no small part in the evolution of man.”

We climbed a well-worn path inside a narrow gully to a kind of platform of alluvial soil with in the center a mud pan. A hundred yards higher up was another platform, this one with a clear spring containing plenty of fresh water in spite of, or perhaps because of, a thick layer of floating vegetation. This spring is Samuchoso’s nearest water supply. Its name, he told us, is Masashango, adding that the first time he came to draw water he found the spring “guarded” by a huge snake. He withdrew hastily, fell on his knees and implored the “Spirits” to let him use the water from the spring. When he turned around the snake was gone and he has used the well ever since.

The path climbed still higher until we came to a gap between towering cliffs opening out into a wide yellow-grassed valley with Acacia, Combretum and mogongo-nut trees. We found ample evidence of previous Bushman occupation: remains of small beehive-shaped huts and a few flat stones with small, round depressions used for cracking the mogongo nuts. The high valley sloped with an increasing angle towards the level of the desert near the gap that separates Tsodilo from Gumbiku. The cliffs on bath sides of the valley bear numerous rock paintings, one particular group showing fine pictures of rhinoceros. (The rhino has disappeared from these areas.) At the bottom of the valley Samuchoso led us to low caves and showed us numerous large flat stones and boulders in which a regular pattern of shallow cups had been carved. These could have been used to crack mogongo nuts except that most of these slabs and boulders were reclining at an angle which would have been a serious handicap to such an activity. The regular pattern of holes suggests an African game with pebbles, called marabaraba in Tawana but for this purpose too would the slanting surfaces be an impediment. It is possible, of course, that the slabs had been dislodged by rock-slides or earthquakes.

On the second day, having planned a complete tour of Gumbiku, we woke at dawn and found the temperature to be 45°F. which is darn cold remembering that we were in Africa. The trip took us almost a whole day, not only because of the frequent stops to look at rock paintings but also because of the hard going in very deep sand, especially on the east side. The rock paintings decrease in numbers towards the northern end of Gumbiku. It is here, however, that one finds most of the human figures, unmistakably of Bushmen. One was of a woman with a baby on her back, her steatopygian buttocks leaving little doubt about her race, There are several men, the exaggerated size of the male organ leaving little to the imagination.

Half way along the western wall of the hill, Samuchoso showed us a spring located in a very deep hole in the cliffs, called “Tsokam.” From this vantage point one gazes across the Kalahari with the same unobstructed view as over an ocean. From this angle the desert looked more like a uniform tree savannah. Two ostriches were picking their way between the trees unaware of our presence. To the north, the depression between Gumbiku and Biengwa is covered by a pure stand of Acacia gillettiae, a favorite hideout of large herds of kudu, we were told. We rounded the northern extreme of Gumbiku about noon. Here huge boulders, no doubt broken away from the high cliffs, form a sort of natural rock garden, wild and very beautiful. Samuchoso had no name for this spot so I christined it in my diary “Inspiration Point.” We found no rock paintings on the eastern side of Gumbiku. This side is well wooded with large trees of several species, typical of deep sandy soil, including the mogongo nut tree and some young baobabs.

The going in the mid-afternoon sun was very heavy and we were glad when we neared the southern end of the hill. We saw large groups of vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) quite at home on the high, jagged cliffs. We came through the gap between Gumbiku and Tsodilo which I named “Bushmen’s Gate” in my diary. We reached camp in the late afternoon. tired and thrilled. The night was calm and soundless.

The next morning we broke camp, packed and were away at nine. After some miles we stopped and looked back for a long time with the sad feeling that we would never return. We kept on looking as we drove away until the hills blended into the distant heat waves, real no longer but part of African legends and myths.