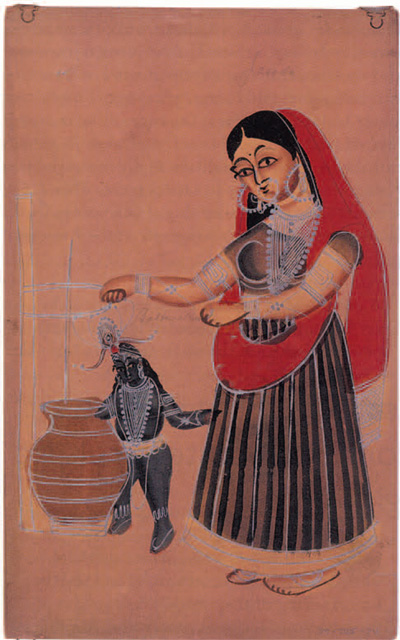

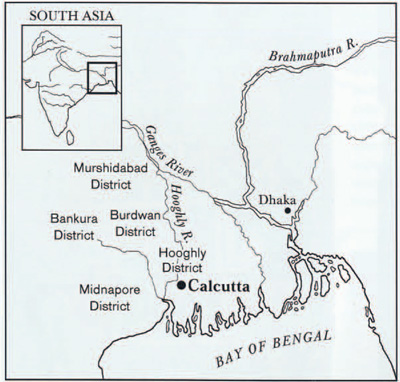

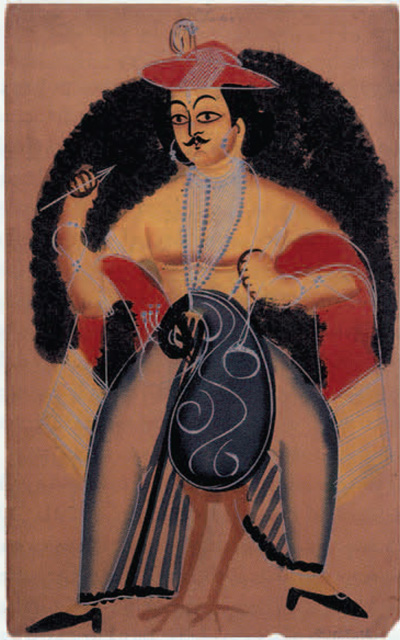

Kalighat paintings, as the name suggests, were created in the Kali Temple area on the ghat (bank) of the Burin Ganga (a canal diverging from the Ganges River) in south Calcutta (Figs. 1, 3). From at least as early as the 1830s until the 1930s, the images were painted and sold as pilgrimage and tourist souvenirs, not only in the shops and stalls lining the alleys of the Kalighat area but also in other temples in the city. These inexpensive pictures, executed with swift brush strokes on cheap paper, would have been purchased initially as mementos of a trip, and subsequently would have decorated a home or been consecrated to embody the depicted deity and worshiped at a home altar.

Museum Object Number(s): 17844

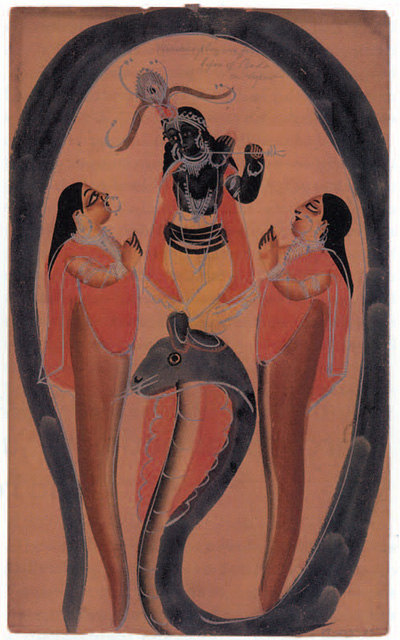

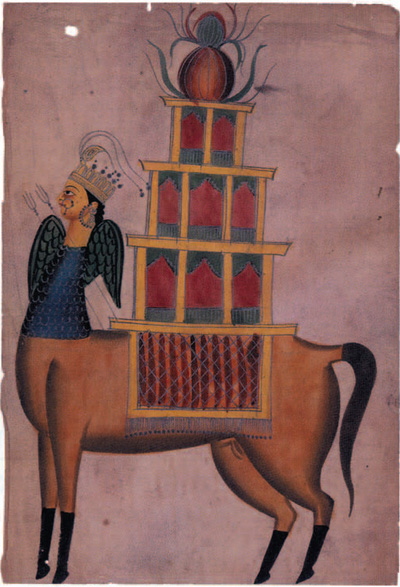

Despite its link with the famous Hindu temple, the painting tradition was diverse enough in its repertoire to include subjects from other religious traditions, as well as non-religious themes. Popular Islamic representations included the prophets and angels and taziyas (tomb models; Fig. 2). Contemporary events were depicted in series of drawings and paintings, and literary scenes from contemporary novels, depictions of popular proverbs, and genre scenes were equally popular (Fig. 4.). Depictions of life in Calcutta’s cosmopolitan hub, its English rulers, the emerging Bengali upper and middle classes, and the supporting classes (servants. prostitutes, wandering mendicants) have survived in large numbers (Fig. 5). Having flocked to the city, abandoning the uncertain income from performances at rural fairs and festivals, the painters (patios) appear to have recorded what struck them as distinctive about the urban setting in which they found themselves. Kalighat renditions of traditional Hindu deities also indicate the profound impact of the British colonial capital on the artists (Fig. 6). Goddesses wear Victorian crowns, play violins instead of veenas (the traditional string instrument associated with Saraswati), and adopt the elegant poses of English noblewomen. These deities are often framed against the heavy curtains of the English playhouses of the city (Fig. 7). As ethnographers, the patuas were not unlike their European counterparts, artists like the Daniells or the engraver Balthazar Solvyns, who sketched prolifically during their travels through India.

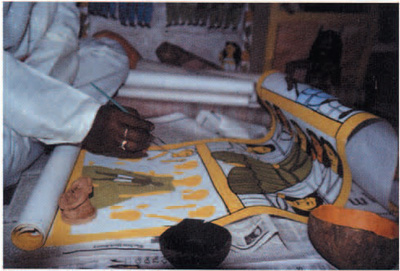

The works of the patuas supplied the city’s fledgling tourism industry, stimulated by the influx of visitors brought by new modes of transportation—trains, steamships, and horse-drawn trams. As items of mass production for a mass market, this genre of painting exhibits marked repetition of topics and iconographic formulas. Their production process was characterized by a division of labor. A master painter often penciled the basic form which his family members would then ink. It is really as souvenirs, not unlike postcards, that we must understand works such as those in the Sommerville collection in the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Since the paintings were never intended to be unique in the way we anticipate works of art in a Western cific settings (Fig. 8). Other changes included the use of paper rather than the traditional medium of cloth, and a preference for quick-drying watercolors in the place of gouache and tempera. Scholars from W.G. Archer to Tapati GuhaThakurta and (most recently) Jyotindra Jain have pointed to “the basic imperative of producing pictures cheaply, quickly, and in vast numbers to cater to the growing market of the city” as motivation for the changes in form and format (Guha-Thakurta 1992:18).

Other innovative techniques introduced attest to contact with contemporary European paintings. Shading for volume in the latter was interpreted as a wash of color graded from dark on the outer periphery of the form to the bare central zone. The three-quarter profile was added to the repertoire of frontal and profile faces. The painters’ rudimentary experiments with perspective, however, suggest that these conventions were not understood through training but interpreted through their encounters with and prospered from their roles as commercial and legal intermediaries for the English trade. Kalighat paintings thereby participated in the emergence of Bengali identity in the colonial capital in the face of the increasing Europeanization of the city’s intellectual and cultural life. During this period, the British were altering their position from merchants vulnerable to the grace and protection of Indian sovereigns to monarchs of the territory. Anthropologist Milton Singer’s term “cosmopolitan folk culture” aptly describes works such as these paintings sometimes little modified from its village counterpart and sometimes assimilated to the mass culture of the urban center” (1991:35).

The market for Kaligliat paintings expanded rapidly through the 19th century to include not just Hindu villagers coming to the urban metropolis but also resident bankers and merchants from the region of Marwar in Rajasthan in western India, English administrators, and European missionaries and travelers. Kalighat paintings were carried back as momentos to Britain, Russia, Czechoslovakia, France, and the United States. English scholars and cultural figureheads in India including Sir Monier Monier-Williams and Lockwood Kipling amassed vast personal collections, which are now housed in the Bodleian Library and Victoria and Albert Museum respectively.

Maxwell Sommerville’s Collection

The Kalighat paintings that Maxwell Sommerville gave to the University of Pennsylvania Museum in 1895 reflect his collecting interests. In so doing, they mark a little noted moment in the transformation of these objects from commodities for the tourist trade and documents of ethnographic “fieldwork” to artworks worthy of museums. Sommerville (1829-1904) was a Philadelphian who made his fortune in publishing. From the 1860s on, he traveled through Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, India, Burma, Thailand, China, Japan, and Korea, observing and recording the customs and practices of these foreign lands, in particular their religious beliefs and mystical traditions. During his travels, Sommerville collected voraciously—vast quantities of artifacts of uneven quality and diverse function. The bulk of this eclectic collection, including the 57 Kalighat paintings, went to the Museum.

The Kalighat paintings must first be understood as mementos of particular collecting experiences from Sommerville’s travels in India. As souvenirs, the paintings brought back by the traveler would have been the visual accompaniment to narratives about a remote other world. As Susan Stewart puts it: “Removed from its original context, the exotic souvenir is a sign of the survival, not its own survival, but the survival of the possessor outside his or her own context of familiarity. Its otherness speaks to the possessor’s capacity for otherness; it is the possessor, not the souvenir, which is ultimately the curiosity” (1984:148). While of little monetary value at the time of their acquisition, their worth probably lay in their connection to the collector’s biography, to their capacity to imbue the individual with an exotic aura.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-225-28

Museum Object Number(s): 29-225-29

Kalighat Paintings and the Study of Hinduism

Today Sommerville’s choice of pieces and his notations on them reveal his interests but also speak of trends in collecting and contemporary attitudes toward the “East.” The Kalighat paintings that Sommerville selected from the available range of subjects were almost exclusively depictions of Hindu deities. They include scenes from the biographies of major Hindu gods such as Shiva and his family, Vishnu and his incarnations Rama and Krishna, and the goddesses, all deities that enjoyed a wide circulation (Figs. 9-12). The Kalighat patuas’ more ethnographic endeavors were clearly not interesting to the scholar in search of an “authentic,” indigenous culture, one uncontaminated by the increasingly global tourism of the 19th century (Clifford 1988:1-19) or the overwhelming imperial presence in the colonial capital. Sommerville, unlike some other collectors of the period, appears for the most part to have rejected subjects that responded overtly to this presence.

Rather, his interest in the paintings appears to have been as depictions of the Hindu pantheon he had encountered through the monumental 19th century translations of the Hindu sacred books: the Vedas, Epics, and Puranas. His collection includes most of the major popular deities of the pantheon reconstructed from the Puranic literary corpus. In fact, the set provides virtually a visual analog to the colonial compendia of Hindu gods, in which the earlier generations of Orientalist scholars in search of the Hindu religion had classified the deities by name, function, attributes, and relationships to each other.

The paintings may well have served as a personal study collection for Sommerville, the scholar of world religions. Other collectors of Katighat paintings included scholars of Hinduism such as W.J. Wilkins, who used Kalighat drawings to illustrate the principal deities in his book, A Handbook of Hindu Mythology (Calcutta 1882). Christian missionaries concurrently acquired these works to comprehend the beliefs and practices of their potential converts.

Sommerville’s Western humanist approach inclined him to place more value on the texts than the images. Each work bears an identification of the depicted deity and the brief handwritten notes often occur squarely within the body of the images rather than on their mounts. This suggests that he treated them as illustrations, such as would have been found in contemporary publications, or as tourist souvenirs rather than as deity images or works of art. Neglecting to document any artists’ names at a time when it would have been easy enough to do so also contributes to the sense of this as an ethnographic collection rather than of works of art.

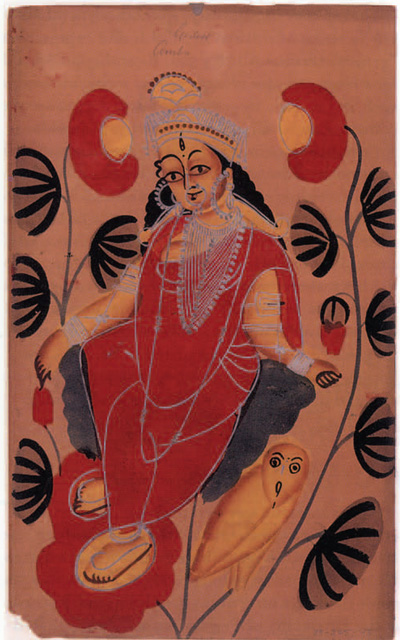

Some labels, written above the heads of figures, provide terse iconographic identifications that are clearly by someone unfamiliar with the visual vocabulary of the Kalighat tradition. Systematic misidentifications also attest to his textual approach to the paintings, in lieu of exploring oral sources or contemporary local tradition. For example, he identified a figure of the goddess Chandi with an elephant (see cover), a distinctively local deity, as Parvati, the wife of Shiva and mother of the elephant-headed god Ganesha, because of a narrative that has survived in song, scrolls, and ritual. Sommerville did not distinguish between the animal associated with Chandi and the anthropomorphic figure of Ganesha with elephant’s head. While the story of Ganesha’s miraculous birth, created by his mother Parvati, is ubiquitous, that of Chandi is not. As an iconographer, Sommerville had not accounted for local distinctions and contemporary ritual needs.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-225-3

Chance, as traditional protector of merchants trading overseas, had much to offer to the burgeoning Bengali bourgeoisie, a mercantile community that had prospered from its recent move to the British capital.

A second misidentification likewise refers to the textual corpus under reconstruction during the 19th century rather than to local beliefs and customs. He labeled an image of a goddess with an owl (Fig. 13) as Ameba, a goddess who was no longer in popular circulation in urban Calcutta or its agricultural hinterlands, though she had been featured in early and medieval narratives, including the epic, Mahabbarata. In contemporary Bengal, however, a goddess with a pure white owl was more likely to have been Lakshmi. The accompanying white owl is to this day considered an auspicious harbinger of a fruitful harvest season and is called Lokkhi Mancha (Lakshmi’s owl).

These Kalighat paintings were transformed from records of contemporary urban life in the colonial capital into documents for scholarly understandings of Hinduism in the late 19th century. They satisfied Sommerville’s search for an authentic. uncorrupted Eastern culture and religion as well as an obsession with taxonomy that marked the particular predilections of anthropology at the time. As self-styled professional ethnologist, he was part of the set that provided the larger conceptual compartments into which acquired objects were slotted. His travels may be perceived as part of the larger network in American anthropological and museum circles that directed excavations and collecting trips to “the field.” Upon his return, he sorted his acquisitions into appropriate categories that were believed, in the world of ethnological museums, to simultaneously reflect ethnicities and material culture (Phillips 1995:107).

Ironically, it is in the appropriate depiction of religious subject matter that Kalighat painting came under greatest criticism from contemporary elite Indian circles. Unlike foreign travelers and missionaries, the coterie of nationalist artists, collectors, and literati who were constructing an art historical canon at the turn of the century located authenticity, that is Indianness, in emotional and spiritual qualities, and denounced the Kalighat tradition for its lack thereof. The civil servant—cultural anthropologist Gurusaday Butt, for example. wrote disparagingly of the Kalighat painters:

A great deal of attention has been given by art connoisseurs to the so-called Kalighat painting, which is the work of the traditional painters of the Matua class. These painters, while continuing the technique and skill in Iine-drawing of their rural predecessors of the past, had about a century ago, come under the influence of the urban life of Calcutta, in the centre of which Kalighat is situated, and had, as a result, lost touch with the traditional ideology of the religious and spiritual motifs which was the soul of the traditional art of the patios… [Even such mythological subjects as Shiva carrying the body of Parvati are found lacking in spiritual appeal in the work of the Kalighat patuas in spite of their skill in line drawing. One feels that something is missing; and that something is the inner spiritual motive or rasa. (1990 [19341: 83-84).

Kalighat Paintings as Art

In the early 20th century, validated by the particularized vision of Modernism, Kalighat paintings were gradually upgraded to “art.” The abstract quality of these works resulting from the sparse composition, elegant line, and brevity in representation of volume appealed to the newly formulated Modernist aesthetic. In 1926 Calcutta collector and critic Ajit Ghose wrote enthusiastically: “There is an exquisite freshness and spontaneity of conception and execution in these old brush drawings…there is a boldness and vigour in the brush line which may be compared to Chinese calligraphy” (p. 98). Contemporary European scholars in Calcutta, who would later become the early curators of South Asian art, also acquired the works for personal collections at this time. In time, they declared Kalighat paintings worthy of collections such as those of the British Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Here in Philadelphia, Stella Kramrisch justified their inclusion in her groundbreaking exhibition, Unknown India, in part by establishing a successful comparison with major Modernist painters:

Kalighat paintings…and brush drawings are monumental in their presentation on an otherwise mostly blank page. Preceding the work of Matisse, some of the brush drawings prefigure it. Out of Indian tradition and impressions of Western painting, the “bazaar” painters, descendants of low-caste and hereditary craftsmen created forms as valid as, and akin to, some of the later work by leading artists in the West. (1968:72).

Implicit in their reallocation from souvenir and ethnographic collections to art museums is a removal of their earlier function as “Bazaar Paintings,” that is, cheap souvenirs of travels or pilgrimage to be picked up in the markets. Instead, Kalighat paintings entered the domain of art, which by the mid-19th century designated a special sphere of creativity, spontaneity, and purity, a realm of refined sensibility and expressive “genius” (Williams 1983:32). As anthropologist Igor Kopytoff observes: “Because it [in this case, such art] is done by groups, it bears the stamp of collective approval, channels the individual drive for singularization, and takes on the weight of cultural sacredness” (1986:81). He has termed this process of transition in the cultural biography of objects “usinguiarization.” Their elevation in status, not accidentally, coincides with the extinction of the living tradition in the 19305. At the time when these objects lost in the competition with mechanically reproducible images, they were removed from the market situation in which they were created and circulated. They have now became rare and tinged with nostalgia in the process and prized in museum collections (Phillips 1995:109).

Museum Object Number(s): 29-225-43

Acknowledgments

This material was first presented at a conference on “Empire, Globalization and Culture” at Middlebury College in May 2000. I thank Lee Horne who had urged me to look at the works since the beginning of my graduate school years at the University of Pennsylvania. She facilitated the research and writing in innumerable ways and offered encouragement continuously. Alex Pezzati, UPM’s Archivist, introduced me to the colorful personality of Maxwell Sommerville; Jennifer White, Keeper of the Asian Section, allowed me access to the works; Jennifer Quick and Helen Schenck of Expedition encouraged and assisted in the writing process. Unless otherwise noted, all figures are from the Sommerville Collection, UPM.

Archer, Mildred 1977. Indian Popular Painting in the India Office Library. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Archer, W.G. 1962. Kalighat Drawings. Bombay: Marg Publications.Clifford, James 1988. The Predicament of Culture. Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Dutt, Gurusaday 1990 [1934]. Folk Arts and Crafts of Bengal: The Collected Papers. Calcutta: Seagull Books. [Written in 1934.]

Chose, Ajit 1926. “Old Bengal Paintings.” Rupam 27-28 (July—Oct. 1926): 98-104. Cuba Thakurta. Tapati 1992. The Making of a New “Indian” Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jain, Jyotindra 1999. Kalighat Painting. Images from a Changing World. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing.

Kopytoff, Igor 1986. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life Things, ed. Arjun Appadurai, pp. 64-94-. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kramrisch, Stella 1968. Unknown India. Art from Tribe and Village. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Phillips, Ruth 1995. “Why Not Tourist Art? Significant Silences in Native American Museum Representation.” In After Colonialism. Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacements, ed. Gyan Prakash. pp. 98-125. Princeton. N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Singer, Milton 1991. Semiotics of Cities, Selves, and Cultures. Explorations in Semiotic Anthropology. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Stewart, Susan 1984. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Williams, Raymond [19761 1983. Keywords. A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Reprint. New York: Oxford University Press.