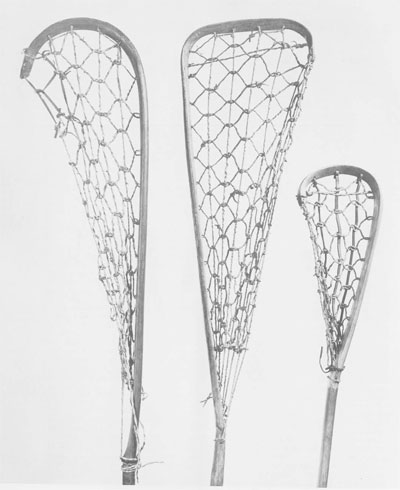

Museum Object Number (L to R): 53-1-17, 53-1-18, 53-1-19

Lacrosse, the great combative team sport among Indians of eastern North America, is today the national sport of canada and is a popular collegiate game in the United States and Great Britain. French Canadians began to play the Iroquois form of stick-ball before 1750. Our name for the game comes from their term for the ball-stick in Iroquois style, la crosse, so called because of its resemblance to a bishop’s crosier, his symbolic shepherd’s crook. Bagataway is also a rarely used name for the game, from its Ojibwa name, Pagadowewin.

As lacrosse has grown in popularity, gradual changes have been made in rules and equipment. The modern sport as played by Americans and Europeans is somewhat different from the original Iroquois version of the game from which it was derived. It has become less violent and some details have been adopted from European games. After Christianization, the Mohawk* of Quebec continued to play their native game, but only as a pastime, discarding its religious associations. French Canadians began its transformation into an international game. It finally spread to English Canadians, becoming their national sport in 1859. Official status resulted in rapid reorganization and standardization. Meantime, the pagan Iroquois communities have kept up to date on all the new developments and frequently meet white teams in formal matches played by the modern rule book. Yet among themselves they have still maintained the original forms of the game and have conserved its old ceremonial associations.

Still another form of lacrosse is played by American women. This is of recent origin and has been reintroduced from Great Britain. Its crosses are imported from England. It has retained the unlimited field of the Indian game, and it differs in many details from white and Indian men’s games.

The Seneca or Cayuga player from a Longhouse (“pagan”) family actually knows three different forms of lacrosse, and he has an intense interest in ancient styles of play. When he and his fellows meet a white team, they play a hard, fast, running game according to the rules of the Official Handbook. When the play is between Indian teams, the game goes by a different set of rules, and is tougher, with more long throws and passes, more body contact, and with many blocks that are defined as fouls in the Official Handbook. In the Indian game, a player may charge, shoulder, tackle, trip, or ram an opponent; he can even strike with the crosse provided that it is gripped in both hands. He may actually use the crosse to lift a runnig man off the ground and dump him on his head; thus a broken collarbone is a frequent accident in the Indian game. Such lacrosse is still ritual combat, a ceremonial substitute for warfare. Finally, the conservative Indian also plays a primitive form of the game as part of religious ceremonies. In these games there are few rules, few players, little biolence, and much emphasis on skill and speed. The game as a rite symbolizes conflict between life and death, good and evil, hope and despair. It also represents warfare between the thunderers and their eternal enemies, the under-earth deities.

A great player knows all three games almost by instinct. He offers us insights into the history of lacrosse, and therefore into the general nature of games and of ritual conflict. What we know of the grand drama of the ball-play has come from a few of these skilled amateurs.

As the game has evolved, ball-sticks or crosses have gradually changed. They form a continuous series from ancient Indian forms to those sold in sporting-goods stores today. The best of our standard crosses for men are made by the Mohawk of Quebec and New York. Indians are especially aware of changes in the game, and recognize different types of crosses as representing earlier stages in the ball-play, the changes in the form of the crosse being related to changes in the game. The history of lacrosse games has been little studied, and the forms of the sticks, which varied from tribe to tribe and from period to period, are poorly recorded. In my attempts to understand and interpret different kinds of crosses, I have found the traditional knowledge of older Indian players essential. Equally critical sources of data are older documented specimens, crosses of known date and place. Unfortunately most of the old sticks in museum collections bear little record.

The University Museum has a set of three from the Cayuga of Six Nations Reserve, Ontario, which are noteworthy for their documentation. Used by three generations of the same family, they span a century in the history of the game. The oldest is also of considerable artistic merit. They were collected by Frank G. Speck from the Cayuga ritual leader Alexander T. General, who bears the venerable title Deskaheh as a chief of the League of the Iroquois. They were given to us by Samuel W. Fernberger.

The oldest specimen was used by Deskaheh’s grandfather, who dies in 1845. The Cayuga ascribe this stick to the “old game,” played prior to 1860. In this stage of lacrosse, the Cayuga played only with Indian teams, no Official Handbook of lacrosse was yet known, and guards had not yet appeared on Cayuga ball-sticks. This crosse is exceptional for its carving and for the refinement with which it was made as well as for its documentation. Therefore, I should point out those details which place it in the early stage of the game, when juggling skills and agility were so important in Indian stick-ball.

Museum Object Number: 53-1-17

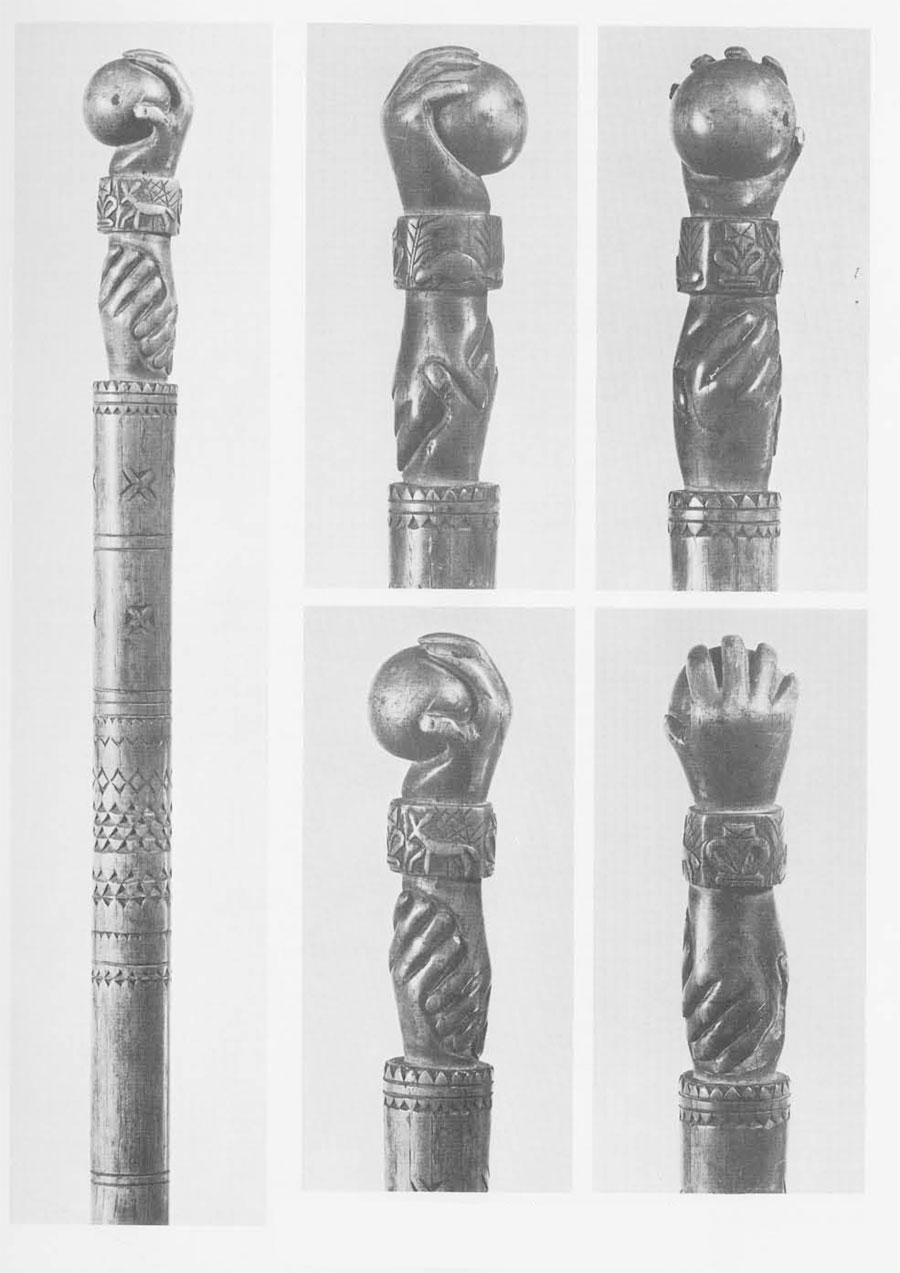

Like our later crosses, it was carved from hickory. Its curve is very close to that of the ecclesiastical crosier. It is netted with a slightly twisted strip of rawhide or babiche, apparently from calfskin. The wood is old, smooth, and patinated, carved in low but bold relief. The tip of the crook is in the form of the head of a dog, with the outermost string of the web coming out of a hole at the center of his mouth. The nose of the animal projects slightly beyond the edge of the web, forming a slight hook which might catch in the web of another crosse. Other Iroquois crosses which are equally old have the outermost string of the web tied into a groove around the tip of the crosse, leaving a small hook of about the same size projecting beyond the outermost string. Our specimen with its carved decoration and drilled string-hole is the most refined of all the old ones. Its outline, net-form, and other functional details are like those of other ancient Iroquois crosses. Its decoration is exceptional.

The animal head probably had symbolic and magical meaning–the stick in pursuit of the ball like a coursing hound. At the butt end of the handle, a human hand grasps a ball, perhaps with multiple significance. The ball may not be touched with the hand but only with the crosse; possibly the crosse is here represented holding the ball as securely as though in the hand. The ball-in-hand was also a favorite motif for the ball-headed war club of ancient times, and this design may refer to the ritualized warfare acted out in the game. Two clasped hands are carved into the grip; these probably symbolize the friendly nature of ball-play conflict, in contrast to the game’s underlying allegorical warfare. The rest of the grip is decorated with delicate geometrical chip-carving. Chip-carving was a favorite technique of American wood carvers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and is well known on old Iroquois objects.

The rawhide net was stretched within the crook to form a flat web, not so taut as the strings of a tennis racket, but without any sag or pocket. The outermost string is in the same plane as the rest of the net. The flat web made for a more difficult game than do the deeply pocketed crosses of the modern game; cradling the ball on the web was one of the demanding skills of the old game.

The crook was made by carving the stick to form while green, the tip being left about two feet longer than it would be when finished. This extra length was then bent to shape in a free curve, with its end lashed against the handle while the wood dried. Then the surplus was cut away to form the open crook, the carving was finished and the thong holes bored, and the net was woven in place. The crooks of the later crosses were shaped in a form.

Museum Object Number: 53-1-17

The side of the crook rising above the plane of the net makes a wall on each crosse. On the oldest stick, it has a thick D-shaped cross section, with its flat face almost perpendicular to the plane of the web. It forms a very low wall, of little use for holding the ball. The curved tip is a thin almond shape in section and forms an angle of about ten degrees with the web.

The second crosse of our set is one of a transitional stage, intermediate between old and new types; it was used by Deskaheh’s father, Isaac General, who died in 1910 at the age of 65. It is for a left0handed man. It has a flat web, but the wall of the crook has a thin D-shaped section, forming a higher margin which would help in restraining the ball. Three guard strings at the outer edge of the net also rise above the plane of the web to form an elementary pocket. At the flattened tip of the crosse, the wall is at a very acute angle to the net, so that it might serve as a scoop. However, the end is less dished than that of the modern type, and the web has no sag, all of the pocket-like effect being due to the higher wall and the guard strings. This is a large stick, four feet ten inches long, with a ten-inch-wide crook and a nineteen inch handle. It meets the standards of the Official Handbook of 1888. Cayuga believe that this was their typical crosse from 1860 to 1890, the stage which they call the “middle game.” The ball was of soft rubber.

The most recent crosse was made by Jeremiah Aaron for Deskaheh in 1932 for use in a ritual game. It represents the modern Cayuga style rather than a standard Canadian crosse, but it meets the regulations of our Official Handbook. It is shorter than earlier Cayuga sticks, and shorter than many modern ones, being only three feet five inches long, with a crook six and one-half inches wide, a handle twenty-five inches long. The wall is a sloped triangle in section, and the crosse has a shovel-like form. The web is formed of lengthwise strips of oil-tanned commercial leather crossed by rawhide, and is pressed down and molded into a section of a cone. Three guard strings and the sloped wall blend into the contours of the pocket, with a very much thinned and flattened tip, so that the crosse is typical of the scoops used in the modern white man’s game. It was designed for use with a hard elastic rubber ball in the “new game,” although it was actually used in the conservative ritual of the Longhouse.

Development of a pocket and addition of guard strings came with spreading popularity of the game among whites; Indians accepted international rules and welcomed matches with any white teams. These modifications began a long time ago, however, and there were also many other unrecorded changes in the history of the game. Guard strings have been required by the Official Handbook since at least 1880. They are intended to prevent catching the web of one crosse with the hook of another, an accident which was not considered a foul in the Indian game. On a guarded crosse, several extra strings are added to the edge of the web, each one of them covering any slight projection of the tip. Absence of guards is the most conspicuous feature of an early crosse. When guards first appeared, they were not interwoven into the rest of the web, but in later crosses the guard strings, which run from tup to handle, are interwoven. In the modern crosse, the guard strings and the wooden frame are integral parts of the pocket, which normally has a depth equal to the diameter of the ball.

Old crosses were more like a tennis racket, while the modern one is somewhat like the wickerwork bat used in the ball-court game of jail alai or pelota. It is possible that lacrosse has even been influenced or modified by pelota. This may be one reason for the evolution of the crosse in the direction of the pelota cesta or basket. Other innovations in modern man’s lacrosse have apparently been borrowed from other sports-the modern goal from ice hockey, the bounded field from one of the European court games. All of the standard innovations have been accepted by Indian players, but have not been admitted into their ritual games.

The conservative Iroquois man plays lacrosse as a religious activity. Outlines of the Cayuga games which follow are based upon the observations of the late Frank G. Speck, who studied the rites of the Sour Spring Longhouse, and upon those of Mrs. Clara Redeye. She, although a Seneca, was formerly married to a Cayuga ballplayer at Sour Spring. Ritual games of other Longhouses probably differ in detail, but these have been little studied. The Cayuga play lacrosse during two different ceremonies.

The Cayuga Thunder Ritual is held in the spring and summer when rain is needed. An outdoor fire serves as an altar for the burning of tobacco, with speeches and prayers. Players have prepared for the game by fasting, purging, and treatment with herbal medicines. Each team has seven players, one team made up of older men from one moiety, the other of younger men from the other moiety. Thus the game is thought of as being played between fathers and sons. The seven players also personify the seven thunder gods.

The field is an eighth to a quarter of a mile long, without side boundaries and with only a goal at each end. Each goal is seven paces wide, marked by a pair of poles set in the ground. Seven goals are required to win. This game is called Gatchiihkwae, “beating the mush,” in reference to the meal provided for the winning team by the losers. The game itself is followed by a prayer and dancing, with a distribution of little gifts to the players.

The other ritual game is played during the Midwinter Ceremonies, at the New Year, but only rarely. A sick person who is under treatment by native physicians may dream about a lacrosse game. This is a dream of conflict, a symbol of the battle between life and death being waged within the patient. Following such a dream, a lacrosse game will be staged outside of the Longhouse during the Midwinter, in that part of the ceremonies conducted by curing societies to pray for the recovery of their patients. The game itself is both an act of prayer and a magical attempt to reinforce the struggle for life that the patient is making. This formal game is the most archaic version of lacrosse played today, and shows ritual survival of old features. It is not used for divination; winning has no significance for the fate of the patient. When the great Iroquois prophet, Handsome Lake, was dying at Onondaga in 1815, he requested a lacrosse game. He had previously included lacrosse in his definitive list of sacred rites, accepted by all Iroquois orthodoxy. As he knew, lacrosse is the game which supernaturals play in the thunderhead, the lightning bolt their ball. Father Jean Brebouf described lacrosse as the most important medicinal rite of the Huron in 1636, and it is still used as a curing ceremony by our Iroquois friends today.

This game is played on the frozen ground and in the snow by barefoot men stripped to the waist. Often they prepared for it by an interval of fasting, prayer, and purging with emetics. Ideally, there should be seven men to a side, each side drawn from one of the two moities of the Cayuga, but teams may be smaller. In contrast to the small team, the field is enormous, as much as a quarter of a mile long, and it has no boundaries except the goals; there are no out-of-bounds. Each goal is a pair of sticks seven paces apart, and a goal is scored by carrying or throwing the ball between the poles. The ball is centered at the beginning by throwing it up, and it is grappled for with the crosses as it falls; it must not be touched by hand or foot. The emphasis is all on skill and speed, with few blocks and little violence. Here one may see the fleet runner showing off his skill, juggling the ball on the net of his crosse during a wild foot race. The more skill, verve, and speed, the better for the patient and the more reason for the gods to be pleased. Often the game is played for a single point, sometimes for two or three. The game is everything, mere winning of little consequence. The losing team, however, provides a meal for the winners, and they may not break their own fast at this dinner except by invitation of the winners.

Of a very different nature were some great games of the past as vaguely known to us through the traditions of the people. As a war game, lacrosse was played between communities of tribes by large teams on big fields. Violent, skillful, crowded games of great importance, they were rituals for settling major conflicts. Sometimes contested land titles or the arbitration of a bitter quarrel depended upon the outcome; the winner prevailed. As an alternative to armed conflict, lacrosse was far better, for at worst it was no more dangerous than football. Since lacrosse was a sacred game, played under the watchful eyes of god and chance, it served as a rite to invoke the aid of the gods on the side of the right. Gaming is often a ritual of divination or a trial of justice.

The ordinary “sand lot” game played by boys and young men and the formal match have by comparison only the quiet overtones of ritual. To be sure, the game delights the Creator as it does the Indian devotee of the sport. In the traditional Indian view, it is a most proper activity for youth. In it, boys are schooled to the values of a man and a warrior. They learn to expend aggressive impulses of the “burnt knives,” a term used in Iroquoian languages for delinquents. Good sportsmanship, clean play, speed, endurance, patience, agility, and the calm acceptance of fatigue, hazard, and hurt without complaint or cowardice are the discipline. The Creator smiles as he watches the game, and is pleased to see his children learning the hardiness and honor of manhood while playing at the Indian stick-ball game of the thunder gods.

———-

*The Five Nations or tribes of the Iroquois were the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. They became the Six Nations with the entry of the Tuscarora into their League in 1720.