Unlace events in more remote periods (the Bronze Age, Classical Antiquity, or even the Renaissance), the events and people of the last century seem close to us, and therefore more comprehensible. The study of the 19th century Middle East seems deceptively easy—there are many, many objects, texts, and even pictures concerned with what went on and what life was like. Images, especially photographs, are particularly compelling. We find ourselves looking into the faces and lives of people whose names we sometimes know, and who might actually have been our ancestors, not in a theoretical, evolutionary sense, but in an actual, historical way.

In recent years, scholars in a variety of disciplines have turned their attention to the Middle East of the 19th century. My own art historical research was on traditional Ottoman women’s dress as a means of studying 19th century Ottoman society. Understanding such issues as how the dress of women changed, who were the fashion leaders, whether European dress was adopted at the same rate by rich and poor, Muslim and non-Muslim, and which parts of the traditional costume were the first to be discarded can reveal a great deal about the relationships among various groups in that society and the process of westernization that went on throughout the century. Given the paucity of systematically collected and reliably recorded examples of 19th century costume, I looked for evidence wherever I could find it. In order to use that evidence properly, however, I had to understand both the contexts in which it was recorded and the audiences for which it was intended.

Biases in the Evidence

Much of the material documenting the 19th century Middle East is European or American in origin. Europeans and Americans from all walks of life—scholars, wealthy travelers, politicians, artists, governesses, itinerant photographers, journalists—visited the Middle East and recorded their experiences in a variety of media. Travel literature, contemporary newspapers and other writing, book illustrations, photographs, paintings, and travel albums all provide evidence of how these visitors viewed their surroundings. The dramatic increase in the quantity of such goods reflects an equally dramatic increase in the number of foreigners who visited or resided temporarily in Constantinople in that century (see box on Tourism).

The use of these sources as historic documents is problematical. When the material concerning a specific place, for example Istanbul (or Constantinople as it was called throughout the 19th century), is examined, certain difficulties emerge. First of all, since the focus of much of it is on the European or foreigner’s experiences in the city, only the Ottomans with whom the visitors or foreign residents would have come into contact appear in their depictions. Detailed descriptions of people, dress, and social customs are almost entirely restricted to the wealthy elite of the city, with only passing references to other groups. Secondly, it is essential to acknowledge the extent to which the impressions of foreign visitors in any part of the Middle East were shaped by their expectations. Secure in their belief in the superiority of their own political systems, religion, and education, few European or American visitors questioned the ways in which the people and the physical setting of the Ottoman empire were depicted in travel writings, guidebooks, and illustrations. The stereotypes of lascivious and indolent harem women, lazy workers, and backward or corrupt politicians living among the decrepit ruins of the past were accepted and perpetuated by most of the people who visited Constantinople. Some visitors were able to examine their surroundings with more of an open mind and their relative openness is reflected in their writing, but the deeply held social and religious convictions of the 19th century Europeans were impossible to shake, and inevitably colored their impressions of what they saw.

On the other hand, the descriptions of Ottoman women, both written and visual, produced by European and American visitors to Constantinople document a part of Ottoman society that is almost completely ignored by other historical sources. With the exception of Ottoman women’s writings about themselves and the women’s magazines that began to appear toward the end of the last century, women rarely have a voice in the voluminous documentation of the 19th century Ottoman empire. Despite the difficulties involved in using the material produced by Europeans and Americans, these sources help to illuminate an often hidden part of Ottoman society.

A Variety of Source Material

Some of the 19th century material—newspapers and travel literature—provides non-visual information concerning the city. At least four newspapers were published in Constantinople during most of the last century for the benefit of the European community residing there: The Levant Herald, Journal de Constantinople, La Turquie, and The Oriental Advertiser/Le Moniteur Oriental. Although none of the papers was illustrated, through their coverage of social events, as well as the advertisements they all carried, the newspapers give us a picture of the life of the European community of the city and the degree of social interaction between Ottomans and Europeans. They also provide an idea of the goods available to both Europeans and wealthy Turks.

Nineteenth century travel literature about the Ottoman empire takes a variety of forms, and the kind of information to be derived from it is to a large extent determined by the category. Travel guides, for instance, are useful for learning how many European-style hotels and restaurants existed in Constantinople at any one time, which newspapers were available, and what sorts of goods were sold by the shops that catered to a European market. Memoirs of diplomats and politicians (who rarely, if ever, met any Turkish women) do not often have accurate descriptions of women’s lives, for instance, but they do describe the diplomatic affairs of the city and particularly the activities of the court. Books written by women are generally the most useful and reliable for social history. A visit to a Turkish woman’s home, or harem, was considered an essential part of a trip to Constantinople, and most women somehow managed to get themselves invited to one. Their visits, often slow-moving social affairs in which eating and smoking were the main activities and children and clothes the main topics of conversation, are always described in detail and thus provide an invaluable source of information about how Turkish women lived.

Other sorts of information are provided by visual sources. The earliest visual documentation of the Ottoman empire appears in costume manuscripts, which were apparently produced for European visitors to Constantinople as a means of documenting some of what they saw in their travels. Dating from at least the 16th century, and continuing to be produced into the 19th century until they were replaced by printed books, the illustrations vary in their attention to detail and their reliability, but provide examples of the clothing worn by members of various groups within Ottoman society (Figs. 1 and 2). The albums generally show one figure per page, with little background, and include the sultan and his court, religious and military officials, street venders, women, and representative examples from ethnic minorities.

In the 19th century the place of the costume manuscripts was taken over by printed books, at first illustrated with poor copies of the manuscript paintings. As commercial printing methods became more sophisticated, these badly reproduced copies were in turn replaced by books illustrated in a variety of techniques, including color lithography. Produced either to illustrate travel literature or as souvenir albums, the images depict both the city and its inhabitants (Fig. 3).

The illustrated books and albums were supplanted, to some extent at least, by the photographs that were available commercially in Constantinople within two decades of the invention of photography in 1839. Sold individually and in albums (and after a few decades, as postcards people and places of Constantinople taken by commercial photographers would seem to be an excellent source of information for social history (Fig. 4). However, even a cursory examination of these photographs reveals them not to be reliable. The photographs can rarely be dated accurately, and in any case, the images created by the photographers reflect a foreign vision of Ottoman life, a vision intended to appeal to the European tourists who were the primary patrons of the photographers (Fig. 5). The individual and family portraits taken by the same photographers for Ottoman subjects are potentially a much more reliable record of contemporary life.

Nineteenth century paintings are less numerous than photographs and present a different view of the people of Constantinople. For European painters interested in Oriental subjects, as they were known then, Constantinople was a popular destination, and depictions of harem women found a wide audience. The Orientalist painters often executed their work in pains taking detail, providing at first glance excellent visual documentation of 19th century clothing, interiors, and lifestyle (Fig. 6). The works of the French artist Jean-Leon Jerome (1824-1904) and of John Frederick Lewis, a British painter, are particularly good examples of this deceptively realistic style of painting. However, as with commercial photographs, a careful study of the Orientalist paintings reveals that they should not be used for documenting contemporary fashion, furnishings, or even Ottoman life generally. The painters were particularly interested in romantic or exotic images that captured the Orient of their imaginal-Lions, not the Ottoman empire as it existed in the second half of the 19th century. The European-style dress legislated for men in 1829 and adopted by many Ottoman women by the 1860s does not appear in the work of the Orientalist painters, for instance, nor do any of the many aspects of contemporary Ottoman life that reflected the growing influence of European technology or architectural style.

From the mid-1800s onward, a number of Ottoman artists began to work in a European style, painting on canvas with oils. They chose a variety of subjects, although landscape and still life were among the most popular. One of the most well known of the Ottoman painters is Osman Hamdi (1842-1910), the director of the Archaeological Museum in Constantinople and also the first director of the newly founded School of Fine Arts from 1883 until 1908. He spent 12 years in Europe, perhaps studying at some point in the studio of Gérome himself. A great deal of his work resembles that of the Orientalist painters, and he often painted women in the harem (Fig. 7). Much of his work reflects his interest in recording aspects of traditional Ottoman life, but he also painted portraits of women in contemporary dress (Fig. 8). Osman Hamdi’s work is thus of more use for social history (and costume history) than much of 19th century painting, not least because as a Turk, Hamdi would have had a much better acquaintance with what Ottoman women actually wore and how they lived. His European counterparts would rarely, if ever, have met any Turkish women, and must have used Greeks models.

A Nineteenth Century Souvenir Album

The tourists who purchased the travel books, picture albums, photographs, and paintings described here took their souvenirs home with them, and these objects may now be found in many European and American libraries and museums. One such souvenir album is in the collection of the Rare Book Room of the Van Pelt Libarary of the University of Pennsylvania (Figs. 9-11, 13). Acquired by the library in 1889, the album of color lithographs entitled Stamboul: Souvenir d’Orient was originally purchased by someone named B. Moore in May 1866 in Constantinople. The book contains 28 plates, most of which show two or three figures in an outdoor setting, done by a Maltese artist named Amadeo Preziosi.

Amadeo Preziosi (1816-1882) was born into a high-ranking Maltese family. Although his father wanted him to study law, Preziosi pursued his own interests in art, first in Paris and then in Constantinople where he settled, probably sometime in the early 1840s. He and his Greek wife lived in the section of the city called Pera (see box on Tourism). It is clear from the quantities of Preziosi’s work that survive in public and private collections that his drawings and watercolors were in great demand (Llewellyn 1985). Much of his early work was done on commission, but he also seems to have done a great number of sketches and paintings because the subjects interested him. In his first decade in Constantinople, Preziosi painted portraits either of individuals (Fig. 12) or types, such as a barber or a bread-seller. These early works, many of which are just sketches, are sensitive, detailed representations of actual people. Some include a background, while others show only the figure, with most attention given to the face and dress of the sitter.

By the mid-1850s, Preziosi was very well known among the European community of Constantinople. Visits to his studio were an important part of many tourists’ itineraries, and are often mentioned in the published accounts of their journeys. Mrs. Edmund Horuby, the wife of a British official, who lived in Constantinople for several years, writes of a day in 1856, “We looked in at Signor Preziosi’s on our way home and admired his beautiful sketches of this place, groups in the bazaars, and fine old fountains” (Hornby 1863:157). A similar visit is described by Lady Anne Brassey, a British woman who visited Constantinople twice, in 1874 and 1878 (see Brassey 1880: 101).

Perhaps it was because of the increasing demand for his work that Preziosi went to Paris in the late 1850s in order to supervise the publication of a volume of his Constantinople sketches. The original album, Stamboul Recollection of Eastern Life, had 29 lithographs and was published in 1858 by Lemercier. There is no lithographer’s signature on any of the plates, an indication that Preziosi himself may have done the work, as is held by family tradition (Llewellyn 1985:10). The book, which was sold in Europe as well as in Constantinople, was successful enough to be reprinted a number of times.

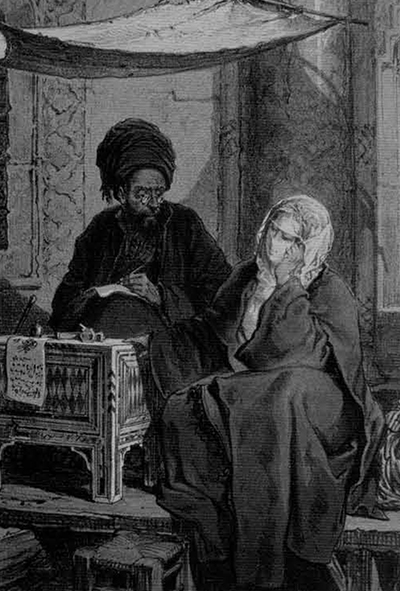

The subjects of the illustrations are identified by French titles on the table of contents, which is at the back of the book. Many of the titles describe the social types that visitors to the city would have expected to see: Ecrivan public (Letter-writer; Fig. 9), Derviches mendiant (Begging dervishes), Eunuque du serail (Palace eunuch), Les Grecs (Greeks; Fig. 10), and Le Porter de l’eau (The waterseller). All of the plates include some background or setting for the figures, but seven of the pictures carry titles that describe the place, not the people, depicted. Several of this group illustrate the same subjects that had been appearing in travel literature for several decades, and thus would have, been familiar to visitors before they even arrived in the city: Le Bosphore (The Bosporus), Cimetière (Cemetery), and Interieur d’un café (Cafe interior). Others show shops in the covered bazaar, which was perhaps the single most popular spot for tourists to visit. Although the title of only one picture specifically refers to women (Dames Turques a la promenade/Turkish women taking a stroll), women appear in more than half of the illustrations. In several cases they are the main subject, for instance, Les eaux douces (The sweet waters; Fig. 13) and La tasse de cafe (The cup of coffee; (Fig. 11). Women figure more or less prominently in many illustrations of other subjects: Ecrz-van public (Fig. 9), Les Grecs (Fig. 10), Bazar des soieries (Silk bazaar), and Juifs (Jews), among others. The 28 plates of the album are thus a collection of the people and places that most tourists would have seen or hoped to see.

The illustrations share a common style. The light brown paper of the original watercolors and the bright, harmonious colors together give the compositions a warm air. The artist includes a great deal of detail in each image, but there are no sharp lines or harsh contours. The soft light and shadow, flowing garments, and relaxed, often languorous poses add to the romantic impressions that the pictures create.

According to the title page, Stamboul: Souvenir d’Orient was published in Paris in 1865 by Lemercier, a prestigious publisher in mid-century Paris. It appears to be a reprint of an 1861 album of the same title, which is in turn apparently a reprint of Preziosi’s first album of lithographs, Stamboul Recollections of Eastern Life, also published by Lermercier in Paris, in 1858. The original book had one additional image, Juardhouse, that does not appear in the later versions, but otherwise the books are virtually the same. Preziosi’s work was again reprinted in 1883, when it was brought out by CansOn Librarie-Editeur of Paris as Stamboul: Moeurs et Costumes, number seven in the Encyclopédie des Arts Decoratifs de l’Orient. Lemercier also published Preziosi’s views of Cairo as Souvenir du Caire in cab. 1863; this too appeared again in the 1883 Encyclopédie (Llewellyn 1985:55).

The publication of Preziosi’s albums was a commercial undertaking, intended to appeal to tourists and armchair travelers. The views of Constantinople that appear in the albums differ from Preziosi’s other work. The sensitive depiction of individuals has been replaced by a more lively and dramatic representation of types that sometimes approaches caricature. The empty background of the sketch has become a fully developed setting for the figures, so that the scene is much more complete. The images included in the album (figure types, landscapes, and many women) have all been chosen to conform to contemporary European or American images of Constantinople.

Preziosi’s scenes of Constantinople are of interest for two reasons. First of all, despite the obvious concessions to the romantic or picturesque in his lithographs, his work is fairly accurate. Since Preziosi made his home in Constantinople and was related by marriage to the Jreek community of the city, he would have been able to see much that would not have been accessible to many of the other foreign artists working at the same time. Secondly, the varied nature of his work and the amount of it that has survived allow a very instructive comparison to be made between the sketches and portraits he did on commission or for himself, and the more commercial lithographs. The differences in style and subject matter between the two groups are indicative of the extent to which an artistic image is shaped by the audience for which it is intended. Preziosi’s lithographs depict the same subjects that had appeared in numerous books of the same time and earlier, in a style that was intended to satisfy the expectations of the purchasers of the albums.

Nineteenth Century Images as Historic Documents

Scholars of 19th century Constantinople, and indeed of the 19th century Middle East more generally, are fortunate in having a very large quantity of contemporary documentation by European and American artists and writers with which to work. The range of material available for a study of women’s dress, for instance, can be duplicated for many other fields. However, as this review of the 19th century documentation of the Ottoman women of Constantinople is intended to show, the use of contemporary images of the Middle East as historic documents must be carried out with extreme caution. Written descriptions and visual representations often reflect the preconceived notions of the writer or artists or the expectations of the audience. They may also be complete fabrications, in either the part or the whole.

But if some of this material turns out to be less than useful in the investigation of a specific aspect of Ottoman social history, it is of use in another way. As documentation of the ways in which Europe and America looked at, described, and interpreted the Middle East in a period of rapidly increasing contact between the two cultures, the contemporary material provides unique information about the perpetuation of stereotypes, the changing images of an unfamiliar society, the effects of contact between the two cultures, and other issues critical to the study of cultural interaction and social change.

Tourism in 19th Century Constantinople

The rising popularity of Constantinople as a tourist destination is due to several factors. The most important of these is the beginning of regular steamship service to the Ottoman empire from European port cities. The first steamship arrived in Constantinople in 1828. By the mid-1830s the ships serving the city were fairly numerous, and by 1844 a British tourist could choose between five different routes to get there. The Russians, Austrians, and French also had service to Constantinople. There was a substantial expansion of both diplomatic and commercial contacts between the Ottoman empire and European powers during the 19th century, which led to a larger resident European community in Constantinople, as well as to increased tourism.

European visitors to the city generally stayed in Pera, the district of Constantinople in which most of the foreign embassies and churches were located. Pera was also the area of the city in which the hotels, restaurants, and shops that catered to Europeans could be found. Although nearly all tourists crossed the Golden Horn to the old city of Stamboul in order to sight-see and shop in the Grand Bazaar, they were also able to acquire souvenirs from the photographers’ studios, bookstores, and artists’ studios located near their hotels in Pera.