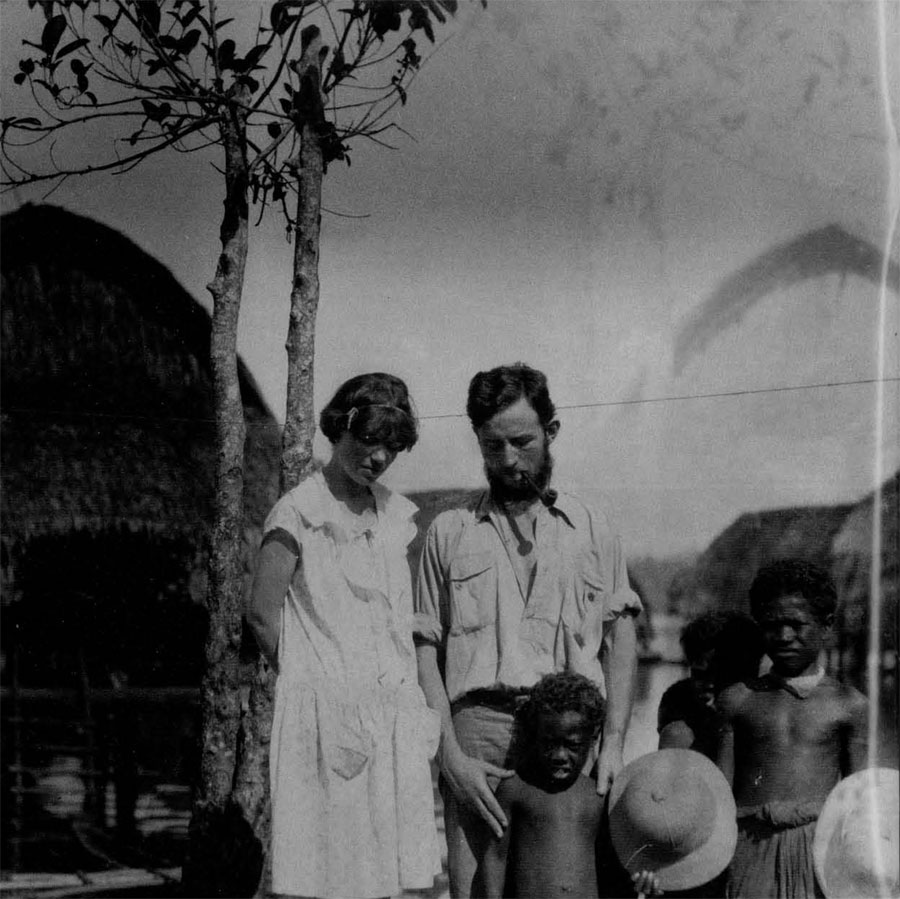

In 1928 the newly married young anthropologists Margaret Mead and Reo Fortune lived for six months in a village called Pere, off the south coast of a small island called Manus in the Territory of Papua New Guinea ( Figs. 1, 2). Toward the end of her life, on the last of her seven visits to Pere Village, Mead delivered this message to the younger generation of a people whose culture had undergone a radical transformation since her first visit almost five decades earlier:

Now its very important that the new generation—the young people who have gone away to school, who have learned English, who have brought hack new customs with them—it is very important that they also remember the ways of their forefathers. If they forget entirely the ways of their fathers, the ways of their grandfathers, the ways of their forefathers they forget where they lived and what they did—they will be people who have no ground under their feet, people who have no roots in the grounds. They will dwell only in the present and have no idea of the past. —”Margaret Mead’s New Guinea Journal” (1967 film)

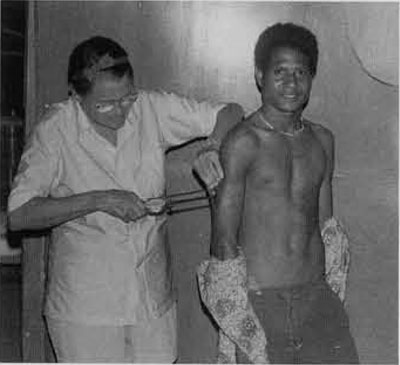

This is the story of helping a village remember its past. I first heard of Pere Village, Manus Island, and the Territory of Papua New Guinea in 1958 when Margaret Mead asked me to analyze anthropometric measurements and somatotype photographs taken in Pere. Theodore Schwartz, then a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, had collected the data at Mead’s suggestion. I was so persistently interested in the Pere somatotype study and the people that Mead invited me to do a follow-up study.

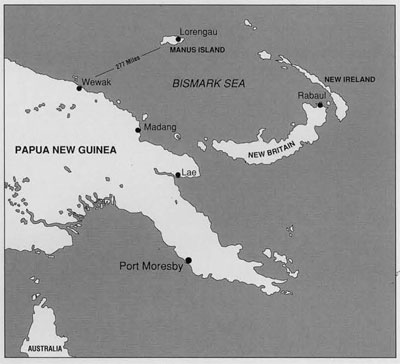

So it was that in February 1966, at age 56, I made my first trip to Pere Village. Unlike Mead and Fortune, whose arduous sea voyage took weeks to complete, I flew by jet from San Francisco to Sydney in 18 hours, spent a night in Sydney, flew to Port Moresby on a smaller plane, and to Manus on a DC3—that small workhorse “prop” survivor of World War II. The last lap, a 20-mile trip from Lorengau to Pere, was still by outrigger canoe, but now propelled by an outboard motor.

On this first trip, Mead’s friend Kilepak was the canoe captain. Soon after we left the little Loniu Bridge wharf, he sat down beside me and said, in Pidgin, that he understood I was a friend of “Margaret Mid”; that it meant we would be friends too. And so we were to the end of his life, over 20 years and 15 visits later.

In 1966 the village still had few physical amenities—no running water, no electricity, no telephones (see box on village). Mead’s house was palm-thatched and unwindowed; there were two rooms plus an attached “haus kuk” (kitchen). What Mead referred to as “latrines” were segregated structures, built over the lagoon, with thatched roofs and sidings. They were accessible by long log walkways with alarmingly wobbly rails made of slender stripped sapling trunks. Mead’s house had a private “one-hole model, with a toilet seat she had brought with her in 1953. A scruffy length of burlap, hung in the doorway, provided a modicum of privacy.

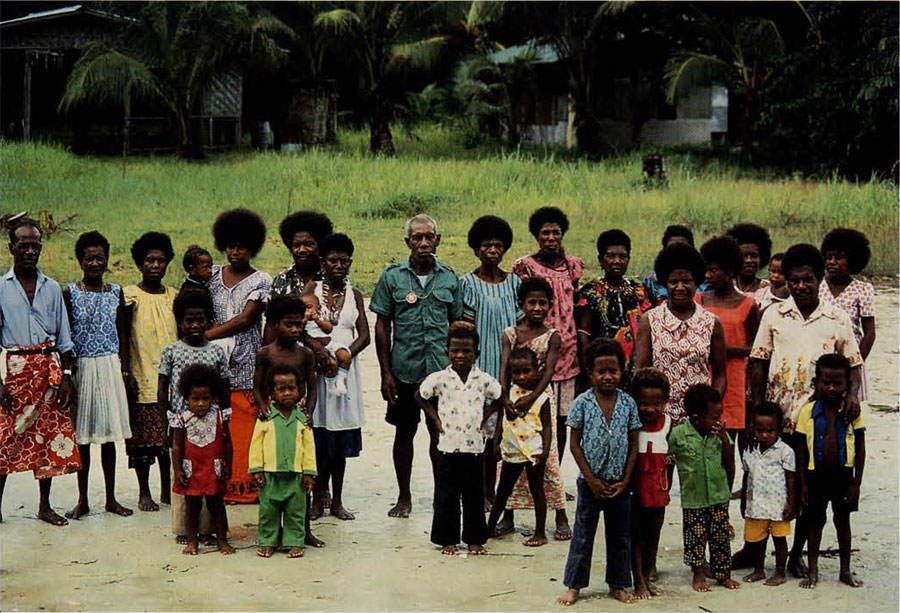

While my main task on this first trip was collecting somatotype data (Fig. 6), Mead’s meticulous field notes, village census records, and sketches of family genealogies focused my attention on the dauntingly tangled web of interrelation-ships among immediate and extended families, among clans, and between villages. I spent an increasing amount of time recording family histories, and I elaborated, updated, and typed out genealogies. The villagers’ intense interest and articulate delight in their typed family trees reminded me that Pere had no written history to bequeath, no tangible reminder of the heritage Mead had admonished them to remember.

Pere Village

Pere is the home of the largest and most powerful clan on the south coast of Manus. In 1928 it held about 240 persons living in 45 palm-thatched houses built over a tidewater lagoon. Located about a quarter-mile from the shore of Manus Island, the village lay inside a coral reef that protected it from the sometimes storm-tossed, always shark-infested Bismarck Sea.

Shortly after World War II the Manus people living along the south coast rebuilt their villages on shore. Pere and its neighboring village of Patusi united as one village, with a population that, until recently, has numbered about 500. The houses they built on land closely resembled their traditional houses, whose raised design enhances circulation and provides convenient storage area for coconut shells (the fuel used for smoking fish), extra poles, thatch, fish nets, and even outboard motors that are no longer working (Fig. 3). Fishing has been and continues to be the chief economic resource of these coastal peoples (Fig. 4).

A Mourning and a Celebration

In 1978 Mead’s terminal illness prevented her returning to Pere with us. When she died in November of that year we notified John Kilepak and the head of the village government, who responded by cable: PEOPLE SORRY OF MARGARET MEAD’S DEATH. WITH SYMPATHY, RESPECT. RESTED SEVEN DAYS. PLANTED COCONUT TREE MEMORY OF GREAT FRIEND. This message told us that the village was mourning for Mead as they traditionally mourned the death of their own great leaders (‘big men,” chiefs in the past). We recognized that it was a plea that we come to Pere to share in the ceremonies.

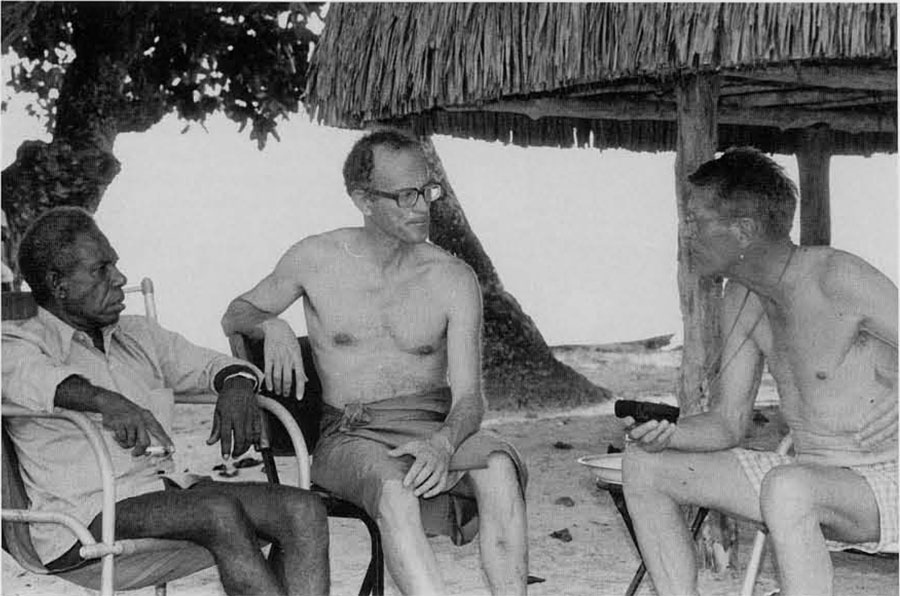

Accordingly, Theodore Schwartz, my husband Fred, and I flew to Pere to honor Mead. When we arrived we were ushered into a nearly completed building that the people referred to as a community center. Kilepak told us that although they hoped to complete it, the funds appropriated by the provincial government plus some money collected in time village had been insufficient (hardly a unique circumstance). He added that they would like to dedicate the finished building to the memory of Mead. The hint was clear. The circumstances favored a generous response. We pledged a gift toward its completion and asked a few of Mead’s friends and admirers for modest sums. The response was prompt and generous. (A plaque near the entrance of the community center lists the donors.)

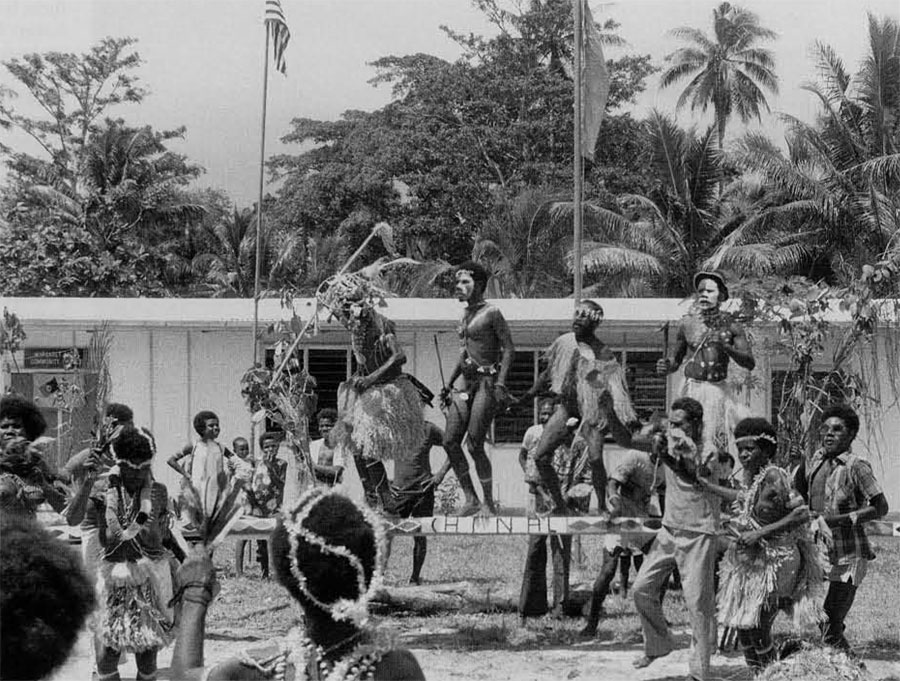

Kilepak, ever imaginative and resourceful, led in making plans for a festive dedication of the Margaret Mead Community Center. He proposed that Mead’s daughter, Mary Catherine Bateson, her 11-year old granddaughter, Vanni Kassaiian, and her longtime friend and colleague, Rhoda Metraux, come to Pere with Theodore Schwartz, Fred, and me for the dedication ceremonies the following year; 1979.

Kilepak then revealed that he also wanted to revisit America before the dedication. (He had lived with my late husband, Scott Heath, and me in Carmel for six months in 1969.) He showed us 65 large Papua New Guinea kinds (coins the size of a U.S. silver dollar) that he had collected in the village. He proposed that he present these coins to the American Museum of Natural History, where Mead had worked for 50 years, in her memory. He had in mind a ceremonial string, symbolic of the strings of dogs’ teeth that figured prominently in ancestral ceremonies. Several of his younger relatives and friends tried to discourage him from making the trip, but lie stubbornly insisted, “advanced age” and “poor health” notwithstanding. (As it turned out, he lived another nine years.)

Kilepaic spent the late spring and summer of 1979 with us in Cannel, and had a month with Schwartz in La Jolla, where he taught Pidgin to a group of Schwartz’s.