TUKUFU ZUBERI, PH.D., is the Curator of the Africa Galleries. He is the Lasry Family Professor of Race Relations, and Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Zuberi sat down with Expedition’s Editor Jane Hickman and Associate Publisher Alyssa Connell Haslam to discuss the making of the new Africa Galleries.

EXPEDITION: Can you describe the new Africa Galleries for us?

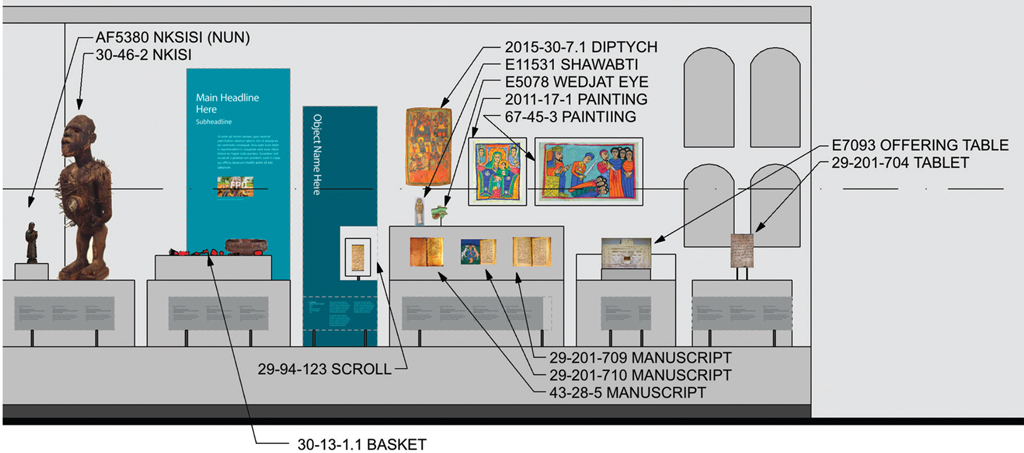

TZ: The new Africa Galleries are redesigned to engage in conversation and to provoke an intellectual curiosity about Africa and Africa’s history, but also how we view Africa and why we view it that way. The data we collected through the Imagine Africa exhibition gave us a certain understanding of how people have been experiencing their time in the Museum. By taking that lead we did something interesting: we organized the new galleries around the idea of decolonization, and around the idea of gaining a new understanding of what the significance of material culture in this Museum could be. Humans need to understand each other, and one of the best ways to do that is through material culture. Obviously, Egypt is so well known because of the circulation of its material culture. We should know about Benin. We should know about Ife. We should know about the Congo. We should know about the cultures of the people in Morocco. We should know about the Ghana Empire, about Ethiopia, about Nubia, and so many more. This knowledge enhances our ability to be a human being and to empathize with each other, because we need to empathize with each other.

EXPEDITION: Tell us a bit more about this idea of decolonization, or decolonizing the museum.

TZ: Decolonizing the museum asks us to consider, how are we looking at objects from Africa? Are we seeing them with a colonial mentality? That kind of mentality is a big part of the problem because it justifies thinking of material culture in a very possessive way—we own it, and we own the ideas about it, as the narrator of a Museum documentary put it in 1940: “we are here to study the primitive peoples of the world.” There is also, in decolonization, recognition of questions of where objects come from—like the Elgin [Parthenon] Marbles in the British Museum, certain Native American pieces, pieces stolen during World War II—and whether to “give” them back. Really, the question is being put to museums, how will you handle these aspects of decolonization and what does it mean? And so rather than being quiet about it we have put it up front in the new Africa Galleries. In our opening statement, for example, we say very clearly that this material culture was either created or collected from Africa in the periods of enslavement or colonialism.

EXPEDITION: How the Penn Museum acquired African objects is complex. How are we telling these stories so visitors understand the original context of objects and how they came into our collection?

TZ: Objects in the Museum’s Africa collection were collected or purchased. We include some of these purchase records in the Galleries, in fact. We’re trying to tell the story of how these objects got here, to the Museum, and part of the story is these collectors and ethnographers who purchased items either on the African continent or from dealers in Europe. African material in the Museum’s collections from Egypt and Nubia—of course also part of Africa—was excavated, which is a different way of bringing Africa into the Museum. Africa has always been a central element of the conceptualization of the Museum, but we’re approaching these galleries with an awareness that visitors have questions about how these objects got here. So, in the galleries, we need to answer three interconnected questions about each object: why this particular object, in this particular place, at this particular time. We give visitors a sense of the object but also of its provenance. Traditionally, African material culture has been presented out of the context of its provenance and even of the Africans themselves. When western viewers first saw brass sculptures from Benin, they claimed they must have been made in Asia or by Europeans. So, this is itself a reflection of a colonial mentality that disconnects the item from the people who made it and the purpose for which it was made. If we take the example of a Kota head: this is a reliquary item, and it’s a protection item that was placed on top of baskets made of tree bark, filled with valuable items and a person’s bones, and buried. So, what happens when you put that in a museum? As an anthropology museum, we can talk not only about the mathematics of its design, its shapes and symbolism, but also about its significance. The ethnographic approach demands that we understand context and that we have self-reflection— that we are critical of our own standpoint relative to knowledge about the object.

EXPEDITION: How long have the Africa Galleries been in development?

TZ: Africa has been a core part of the Museum’s mission, and it has been a core part of my life’s work. I have wanted to improve our galleries of Africa for 20 years. I ended up leaving for a few years to work on PBS’ History Detectives, which put me in more proximity to museum collections and the kinds of collections you don’t usually see, the ones in storage and in the basement. And I was doing that all over the country, generally being more involved in material culture and telling historical stories about material culture. And by the time they asked me to curate a new gallery at the Independence Seaport Museum, I had built a collection of posters that we exhibited here at the Museum. And that exhibit has traveled around the country. (See Expedition 55.2, Fall 2013, pp. 14–17.)

Then, about four years ago, with Imagine Africa on display, we started reconceptualizing the Africa Galleries. It was a big change. And the Museum had the foresight to think about the decolonization angle even before it blew up in public with Black Panther. I thought, I know some really good people who are already working on decolonizing museum space, and this is an opportunity to reintroduce the Galleries completely using modern technology like touch screens and videos, by talking to people in Africa today along with using archival footage and documents that we have, just to reinvent the idea of each object as it is shown.

EXPEDITION: You mentioned incorporating technology into the galleries. How will this shape visitors’ experiences?

TZ: The idea is to work in every dimension with the people who come to see these Galleries. So they will hear music, they will see videos—like one on Africa’s great kingdoms—to give them visual cues. They will see informatics explaining how certain items were made. There will be various timelines throughout, to give people some grounding in terms of the temporal periods that we’re talking about. The interactive maps that we will present will give a different kind of history and a different kind of understanding of the collection in itself. The idea is to be interactive, to invite people to engage with the material in different ways at different levels.

EXPEDITION: Why are these Galleries important?

TZ: We have entered a moment where intolerance is something that some people would celebrate. And they would celebrate that our differences make us incompatible, or our differences make us undeserving, and think why should I empathize with a person I think is unequal and therefore undeserving? Or “less developed,” therefore undeserving? Well, the visit to these Galleries will upend that for Africa, and Africa has received the brunt of this hostility in some ways—it’s not exclusive to Africa, but Africa has been one of those spaces that has felt this conceptual marginalization. Why identify with the Africans? Some people would think that Africa is full of jungle. Even today you have people who have that idea. And then other people who still think that Africa is incompetent and not a full part of the human family. And one way to counteract that is by organizing galleries like this and not ignoring that that is the way people think about Africa. People can have a colonial mentality when they think about Africa. It is our job as an educational institution to undo that. So we have to upend how we show the objects—we have to point people’s attention to how and why they are displayed, to what kind of information we have about how they came to be here and why, to how contemporary artists have reflected on featured pieces in the Galleries.

EXPEDITION: Finally, do you personally have a favorite object or group of objects?

TZ: You know, I selected every single one, all the 300 objects, every little bead on the gold chain, I selected it. And I selected them because I was fascinated by them, and I was fascinated by their story. I always come back to the ivory box from Benin. It’s a beautiful sculpture, probably made in the 19th century. There are two Portuguese figures on the lid, fighting, and next to them is a pangolin (or scaly anteater), with its legs tied. One interpretation is that he represents the Oba, and it suggests that even though the two Portuguese are about to kill each other, they can still tie you up. I’ve heard that a few times, I don’t know if it’s true, but I can see how that symbolic meaning could come from that particular object. So, I really like that.

People can have a colonial mentality when they think about Africa. It is our job as an educational institution to undo that. So we have to upend how we show the objects.