An interview in 1908 with Dr. George Byron Gordon, Curator of North American Archaeology at The University Museum, began Mary Louise Baker’s 30-year association with Maya art.

Her first assignment for the Museum was to draw the Maya pots in the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. Later she traveled to Europe and Central America to locate and draw pieces in both private and museum collections.

Born in Alliance, Ohio, on August 4, 1872, she was a descendant of Quaker families of Chester County, Pennsylvania. She completed her education in Pennsylvania before the end of the last century, and taught there in a number of one-room schools. In 1900 she determined to study art and entered the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art at Broad and Pine Streets in Philadelphia.

As a free-lance artist in the early years of this century, she taught at George School in Newtown, Bucks County, made scientific drawings for Clarence B. Moore at the Academy of Natural Sciences, and did commercial illustration. The drawings, charts, architectural plans, and restorations she did attest to her versatility as an artist.

The strikingly attractive water colors of Maya pottery she had begun in 1908 were finally published by the Museum in 1925 in Maya Pottery in the University of Pennsylvania Museum and in Other Collections (edited by G. B. Gordon). In 1931 she was granted a leave of absence and commissioned to make watercolor reproductions of 100 of the finest examples of Maya pottery, some of which had recently been uncovered in Central America. Starting in the museum at Tulane University in New Orleans, she painted five highly valued vases which had been discovered by Frans Blom. These pieces had been selected by J. Alden Mason, Curator of the American Section of The University Museum, for inclusion in a catalog on Maya pottery.

From New Orleans she went to Yucatan, Guatemala, Honduras, and San Salvador, returning to Philadelphia in September. In a newspaper interview published in December she said:

No woman before me was ever sent on such a trip and I adored every minute of it. You see, my three interests are art, archaeology and aviation, and I was able to combine all three on my visit to the jungles. . . It was my job not only to make drawings of the pottery, but to find good and valuable examples. I did this by getting information from the natives wherever I went. I would sketch one jar and the people who watched me work would tell me of someone miles away who had a beautiful vase that had been in the family for centuries. Sometimes the places were many miles distant over roads that would take me days and weeks by boat and mule. Here is where the airplane came in handy. [Detroit Free Press, Dec. 17, 1931] (It was in 1930-31 that The University Museum sent out the Central American Expedition to do an aerial survey of the land of the Maya.)

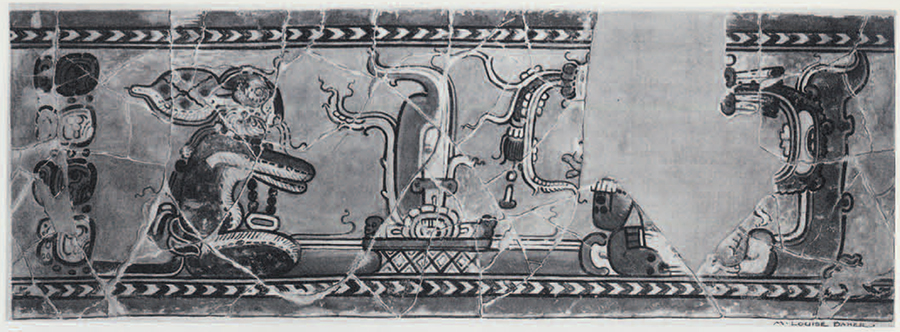

During this same period. J. Alden Mason and Linton Satterthwaite were excavating at the site of Piedras Negras in Guatemala and were sending monumental Maya sculptures back to the Museum. Among the important pieces sent on loan from the Guatemalan Government was a carved stone lintel. Baker made a reconstruction drawing of the lintel which was published in her only article for a Museum publication, “Lintel 3 Restored . . and Why (University Museum Bulletin Vol. 6. No. 4 [1936]). Because of the fragmentary condition of the lintel, sculptured figures were missing and bodily connections lost. Baker had friends sit on a low platform on the Floor in various positions so that she could understand what was anatomically possible in order to fill in the missing portions. She writes in the article:

The seated figures are very human in manner and detail. The left dignitary gently pokes the friend in front to ask what it is all about; the friend, willing to accommodate, vainly tries to peer over the intervening mass of feathers. bracing himself on his foot, in his effort to see—a taut neck-line giving the cue; the next man complacently toys with his tassel, his sleek, round body oozing contentment; the fourth in line is a lean, capable young man, to whom the Chief is evidently directing his words and attention; the fifth, the Patriarch of the row, has slumped in the shadow of his Master, his Fan arrested in mid-air; the sixth, holding his vase upon his knee, absent-mindedly fingers his heads: the last man, and the only one whose face was not completely destroyed, has lost interest after a fruitless attempt to hear and his hand has probably dropped from cupping his ear to toying with his ear-plug.

Baker was an extremely hard worker, often working steadily for eight hours at a stretch, and this aggravated an existing eve condition. Eye surgery became a necessity in 1925 if she was to continue the scientific work she had undertaken. She endured a painful operation without anesthesia that was successful but not permanent, and by 1938 she had to retire, not only from the George School, hut from the Museum as well. She returned for her last visit on January 20, 1962, during the 75th anniversary celebration of The University Museum. On that occasion, J. Eric S. Thompson, in his convocation address, spoke of her, praising her magnificent watercolors.

Baker’s painstaking and beautiful depictions of Maya pottery continue to aid scholars in iconographic and glyphic studies of Maya culture. Fittingly, her association with this institution, begun with paintings of Maya vases, ended with a tribute from an eminent Maya scholar. She died July 15, 1962, a few weeks short of her ninetieth birthday.

- Lintel 3 from Piedras Negras, Guatemala; limestone.

- Baker’s restoration drawing of Piedras Negras (Guatemala) Lintel 3 (publised in the Museum Bulletin Vol. 6, No. 4 [1936]).