Museum Object Number: 29-60-92

Robert Burkitt, who was Penn Museum’s “man in Guatemala” from 1912 to 1937, had an insatiable curiosity bout all things Maya. This went beyond his interest as an archaeologist or his desire as a linguist to understand and record the highland Mayan languages. Although not a trained cultural anthropologist, he was interested in the Maya he knew, how they lived and worked, what they ate, how they dressed, what stories they told, and what they believed. He provided the Museum with a precise explanation of how to build a Maya house, along with an accurate model of such a house, and had it shipped to Philadelphia in 1929. Today’s travelers will find traditional Maya houses have changed very little. Visitors to the exhibit Painted Metaphors: Pottery and Politics of the Ancient Maya at the Penn Museum will have a unique opportunity to see the house model, as well as a model diorama he had made of three dolls illustrating three stages of weaving. This will be their first and only public display; because of their fragility, the models will not travel to the exhibition’s other venues. These views of the house model provide an indication of Burkitt’s insistence on accuracy. Quotations are excerpted from his description with the author’s comments in [brackets].

He explains the words used for a house and its parts:

“Most of the Maya languages—though not all of them have two distinct words for a house. One word takes the house as a mere building. It is the word to use when you say a big house, or a small house, or simply, a house. But if you consider the house as a habitation, and talk about My house, or Your house, or ask if a man is at home, then you have to use the other word.

“The actual sound of the words depends on the language. In the case of the meaning I spoke last of, it happens that the different words, from language to language, are historically all one. The sound may vary as much as from Atút, in one language, to Ichó, in another; but the different forms are connected by gradations. The central form might be something like the Ixil word, Otsóts.

“About the word for a house in the sense of a building, on the other hand, there is no such agreement. The different words seem to center about three types: Na, Pat, and Kab; with no connection between them.

“The rafters of a house are called, in Kekchi simply the sticks. The word for a beam, on the other hand, is a word that means nothing else than a beam, and so with the word for a wall slab. Some parts of a house are named after parts of the body. The door, of course, is the mouth. The ridge is called, by these Indians, the backbone; the skewers (as I’ve been calling them) that stick out on either side of the top, are the horns. And throughout the Maya languages the name for the posts of a house, is something which means (either actually or originally) the legs, as we speak of the legs of a table. And there are whimsical names. The diagonal brace, under the rafters, is called, in this language, the bat-bone, I suppose, thinking of the looks of a bat’s wing. And the original way-up stick, under the rafters, is the mouse-walk.

“One of the spaces between posts is left open, for a doorway. Very often a corner space. In the model, it is one of the middle spaces… the door is open: that is, it is as much open as it ever usually is. You seldom find an Indian house shut up. If the man is not there, his wife or children are there.”

He deliberately left the roof thatching unfinished, to make it easier for the viewer to see the interior.

“The thatching is the least satisfactory part of the model. The fact of the model being a model, and not full size, makes difficulties. In the model the thatch is laced with bark. What is actually used for thatch-lacing, at least in this part of the country, is a certain slender rope-plant, that grows in great lengths. But that rope-plant is only about four millimetres thick, and no plant proportionately slender could be found for the model. For the same reason it would not have been possible to make a palm leaf thatching. There are no palm leaves small enough. And even the grass, though the artist experimented with various kinds, is altogether too coarse and stiff for the model. Finer grasses could have been put in, but they would have been some grass that when it was dry, had no strength in it, and fell to pieces. The result, in the model, is that the thatch, instead of lying down close and smooth, as it would if actual length, has a rough, bristly appearance, which is not at all natural.

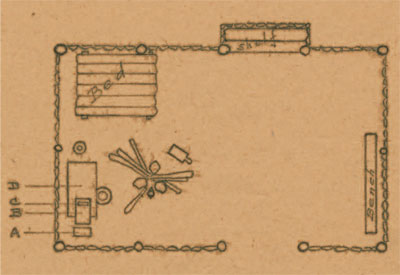

“To speak of the furniture in the model, the floor-plan is like this [see drawing on previous page]:

The fire place is three stones, to put a pot or pan on. The logs are pushed in between the stones…In the corner of the house nearest the fire you have the mill…“A” is the block of wood the woman stands on. “B” and “C” are the lower and upper mill stones; and “D” is the table. The mill stone, the lower mill stone, has three feet: one behind, and that one rests on a post: and two in front, resting on the table… The mill table, in the model, has the defect of being a neat looking board; altogether too neat and carpentered looking. When an Indian wants a wide board, or slab, of course he has no saw; but he has an ax, and a cutlass. And he looks for one of those great trees that have buttress roots, or fin roots, up out of the ground [a ceiba tree?] and chops out a piece the size he wants. The mill table might be some such piece as that. Or it might be a few sticks, side by side, with a leaf over them.

“The bed is always in a corner. It is made of flat slabs, of the same soft wood as the wall-slabs. They are raised a little from the floor, by a log, or something, at the head and foot. The slabs are loose, though in the model they are gummed down; and usually they will be covered with a mat; and a mess of clothes. The bed is a comparatively wide affair. And it is the sleeping place of the woman and young ones; but not of the man. Among these Indians, the man sleeps in a hammock.

“The bed is always in a corner. It is made of flat slabs, of the same soft wood as the wall-slabs. They are raised a little from the floor, by a log, or something, at the head and foot. The slabs are loose, though in the model they are gummed down; and usually they will be covered with a mat; and a mess of clothes. The bed is a comparatively wide affair. And it is the sleeping place of the woman and young ones; but not of the man. Among these Indians, the man sleeps in a hammock.

“A good part of the floor of an Indian house is vacant; in the model, the right hand half. That vacant part is the Indian’s parlour and spare room. There visitors will hang their hammocks, or spread their mats, and you see a bench for visitors against the wall…There is an infinity of things in a house, of course, that there is no sign of in the model. There will be a log beehive, very likely, hung up under the eave. And there will be pots and pans and calabashes and mats and looms and nets, and a turkey in a basket, sitting on her eggs. And up in the smoke over the beams—most important thing of all—the corn and beans and dry peppers. But what an Indian considers the necessary furniture of a house is not much, not much more than what the model shows.

“The hammock in the model, with needless pains, is made like a real hammock…The hammock, in the model, is hung across the width of the house, between the door and the fire. And that would be a common position. But a still commoner position, perhaps, would be in front of the bed. So much that there is an Indian expression—to say that a man has taken such and such a woman to wife, they say, that he has hung up his hammock in front of her….

“In the hall opposite the door, the artist has placed a shallow recess. The recess contains a shelf: and on the middle of the shelf stands a cross. The Indians, of course, are Christians, and however ill furnished an Indian cabin maybe, there is sure to be some religious image, or picture, in it. Placed in a conspicuous place, some little attempt at a shrine. And the shrine, very often, is just such as the model indicates: a recess of the back wall, between two posts. There will usually be some little ornament about it: flowers, or bright berries, or ears of Indian Corn.” [Similar niches would have held deity images in antiquity.]