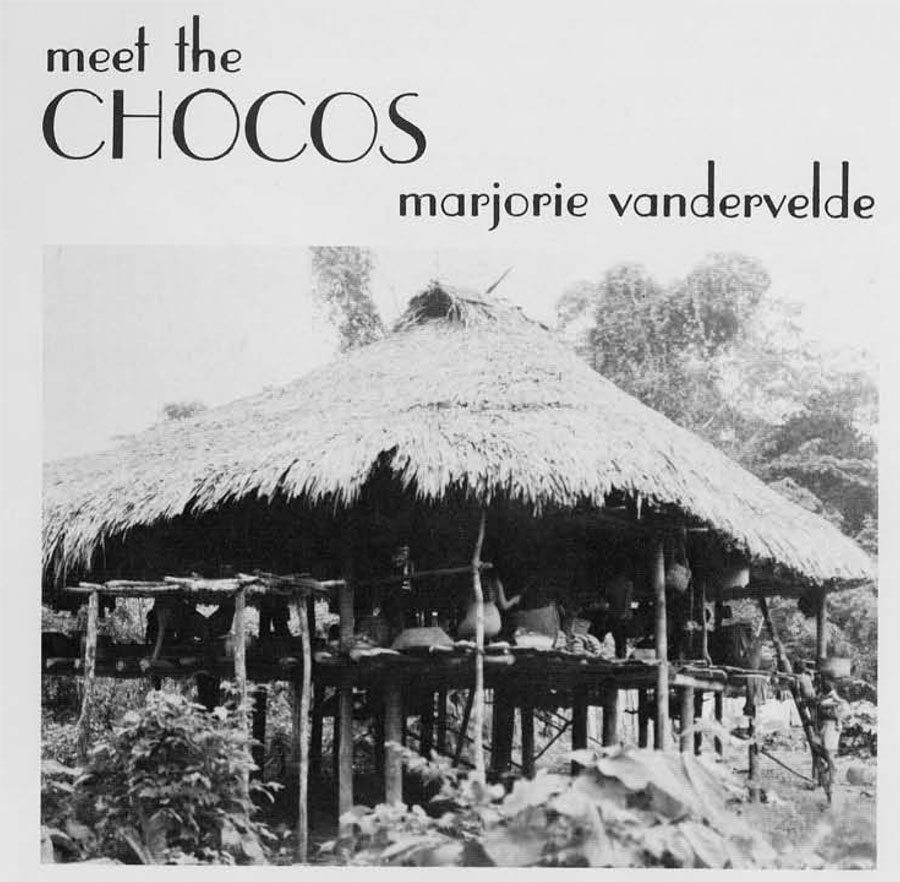

From a small plane we looked down on tangled jungles of Darien Province, Panama. It was a green, undulating carpet crossing into Colombia without a break. Uncut by roads or rails the wilderness was split only by occasional rivers, like silver ribbons, emptying into the Pacific, polka-dotted here and there by Choco Indians’ isolated thatched roofs, balancing on tall poles like long-legged spiders keeping their feet dry.

Three of us, plus interpreter and guide, were soon in a cayuco hewn from a 30-foot log, traveling into the heart of the jungle on Rio Mogue. A few days earlier an ethnologist from Oregon had done the same thing, and had come out with a head wound—creased by a Choco blowgun. But our guide was a good friend of Mogue Chocos.

It is a shock to the psyche, the silent green rain forest, after coming from bumperto-bumper civilization. The river banks crowded us with overhang of vine drapery. Clusters of bulb-shaped nests of the tailor bird hung on one side; on the other were bushel-basket size termite nests used by Indians to bait fish traps. A giant sloth hung from a branch as if it had not moved an eyelash for a century. Howler monkeys used high trees for swings, some branches festooned with purple flowers.

A four-foot iguana dropped to the ground, dislodged from a tree. The antediluvian reptile would become soup for some lucky Choco clan.

Alongside our cayuco the ‘Jesus Christ’ lizards walked on water. They are more correctly (but less picturesquely) called basilisks.

Somewhere in the heart of the Darien’s jungles are the lost gold mines. They originally belonged to the Indians, but were confiscated by early Spanish gold seekers, the Indian owners of tCunas he mines being forced to work as slaves. They rebelled, finally, and killed their tormentors; then allowed the jungle growth to reclaim the mines. The area was called Castilla del Oro (Castle of Gold) by Christopher Columbus, who anchored at the mouth of Chagres River in 1502. He was followed by the conquistadores and the padres in their never-ending search for gold for the coffers and souls for the church.

To this day some Chocos remain suspicious of outsiders.

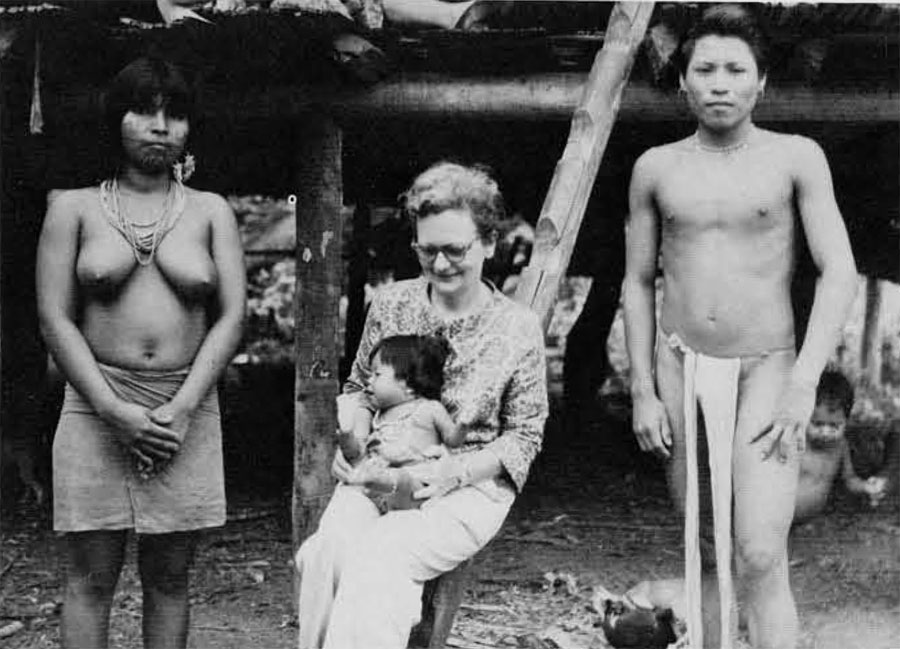

At the headwaters of Rio Mogue stands the tambo which was our destination. Beside the notched log leading to the high floor, a bare Chaco man, with the dignity of a Maya emperor, watched our approach. His build was that of a well-muscled athlete, but his mien was glaringly solemn and he wore only circular earrings and the Choco G-string (a narrow strip of fabric hung from a string around the waist). From the first we called him El Tigre, he seemed that fierce. A quote I’d read in National Geographic of November 1941 suddenly flashed through my mind:

“Chaco Indians deep in the rain forest of Darien paint their faces and repel unwanted intruders with blowguns and poison darts.”

“Chapa!” (Brother!) our guide greeted this patriarchal head of the extended family living in the tambo. He still glowered.

It seemed a propitious time to pull from my trousers pocket a gift of lipstick. El Tigre accepted and examined it curiously. Then, experimented making red geometric designs on his chest and face. We climbed awkwardly up the notched log to meet the clan, for we were to spend the night in this tambo.

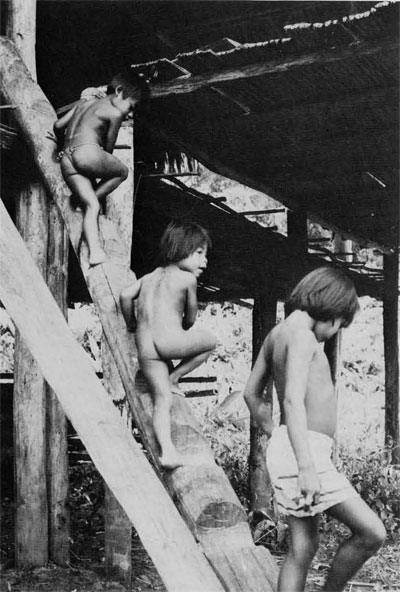

The upended log with notches hacked by machete is a part of every tambo. At night it is simply turned over to put the steps on the under side and thus prevent stray animals and evil spirits from climbing up. Unfortunately it doesn’t keep out vampire bats.

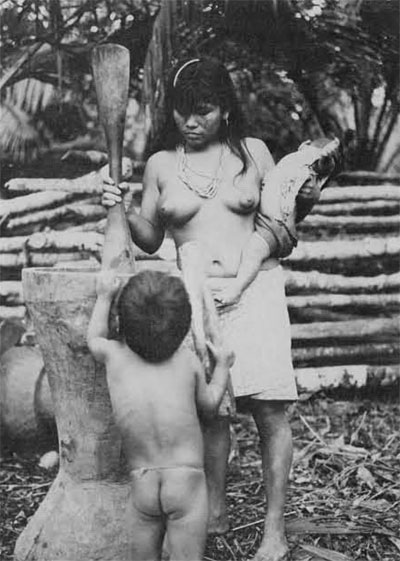

We stepped onto the trampoline-like floor, and into another world. Tawny-skinned women and girls, with waist-length hair and brief sarongs their only cover, went about woman’s work around a log fire—under the direction of El Tigre’s spouse. Creeping babies crept cautiously to the edge of the high floor and peered over. Two women dangled their legs over, and sat combing their long hair; stopping now and then to admire the gleaming highlights. Another climbed the long ramp with a stem of bananas balanced on her head. She had the poise and bearing of a Fifth Avenue model.

I wanted to lend a hand. The only job that seemed to fit my talents was the fire fanning, done constantly where the butt ends of four logs came together (a controlled fire under that thatch). A square of clay, under the fire, was kept wet-down.

With a gesture I asked if I might do the fanning. After a half-hour it did become a bit tiresome, but I didn’t realize I was doing an inferior job until one of the others took over, and went twice my speed. All the women thought my inefficiency was a great joke, and giggled behind their hands. It was a good start—now they believed me when I said we were interested in learning ways in which their culture differed from ours. (Obviously from the fan incident they saw our culture as needing upgrading.)

Darkness in the jungle falls as a curtain. Lamps (candlenut and kerosene) flickered as men of the extended family returned from hunting, and squatted here and there on the big floor to observe us. Our guide, Joe, moved from one to another explaining us. He pointed out our cameras, indicating we would be snapping pictures and this was a friendly activity which they should just ignore.

The candlenut is so fatty that it sends up a sharp flame for several minutes. A dozen of them impaled on a hardwood stick and lighted at the bottom sets off a chain action and burns for some time—creating bewitching shadows under the thatch.

As the lights were burning low, Joe helped me interview El Tigre. Here are parts of that unusual conversation:

Question: Can you tell us the life expectancy of Chocos? (I had searched libraries for this and other elusive information.)

Answer: (After much thought and staring into space.) We Chocos hardly ever die.

Ques: (Trying to grasp that.) Oh’??

Ans: What’s more, you don’t see any gray hair among us, do you? And we Chocos don’t grow hair on any other parts of our bodies . not like you whites do.

Ques: (It seemed a good time to change the subject.) Do you understand about that airplane roaring in the sky above your tambo?

Ans: Of course. It’s a magic thing used by the white man; it flies over the forests often.

Ques: Do your people care?

Ans: (Shrugging) At first we were mad about it. But our blowguns couldn’t touch them; neither could our few guns. So we just forget about them.

Ques: Do you know other countries are probing your lands for a new Panama Canal route? How do you feel about that?

Ans: We can’t give away land that once was our fathers’—and will belong to our children. This land was given to Chocos by the god Acole. How could we give it to somebody else? HOW??

Ques: Does a man have more than one wife?

Ans: Not in the same valley, anyway.

Ques: Is it difficult to build a large tambo like this without such things as nails? (We estimated floor space to be 2000 square feet.)

Ans: A man needs a sharp machete to topple the forest giants, and a strong forest fiber for tying the beams solid. But it is hardest to keep the evil spirits from moving into a new house.

Ques: Your people are on the Pacific side, the Cunas on the Atlantic side. Where you come together, how do you get along?

Ans: We are afraid of their warriors. But they are scared to death of our witches.

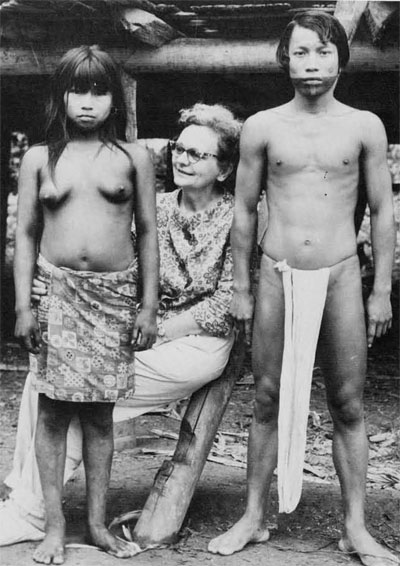

Actually El Tigre oversimplified differences between those neighboring tribal entities. Their social structures are similar in being extended families living together (not exactly clans). But beyond that ..

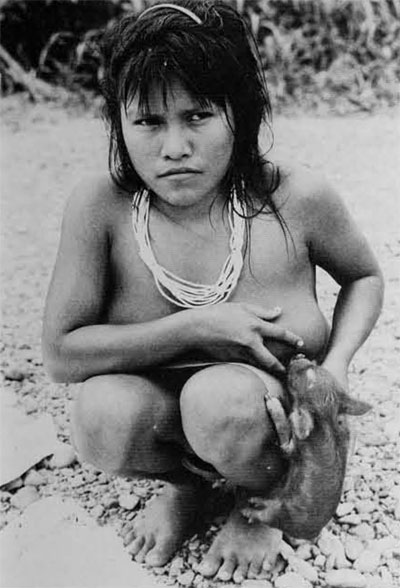

Chaco groups are patriarchal—Cunas are matriarchal at the family level. Chocos could pass for well-built Polynesians except for fine-chiseled facial features—Cunas are inclined to be short and thick, brachycephalic, with features running from Maya to Mongolian types. Choco family groups are loners, choosing to live isolated along rivers—Cunas are strongly gregarious and social, with tight clusters of their homes standing thatch to thatch. Long ago Chocos withdrew into their silent jungle—Cunas have, since Columbus, been brushed by the shipping routes. Choco women are as nude as their men and apparently of equal status—Cuna women are fully dressed and wear the nose ring, an unmistakable symbol of traditional submission.

The Choco tribe has several subdivisions; their language dialects stem from the Cariban. They wander along waterways from the Atrato River of Colombia to San Miguel Bay on the Pacific side of Panama. Their highways are the rivers of the Darien that drain into the Pacific from the spiny backbone of the Andean Mountain system. These rivers are the jungle zip-codes. The river a family group lives along becomes its ‘address.’ And distances are measured by the number of rivers between two points.

On this Pacific side, tides reach as high as twenty feet and push inland up those rivers, making them easy to navigate at high tide. Piraguas are the functional craft, long and narrow with platforms hewn fore and aft so a standing Indian may ‘pole’ them. The cayucos, on the other hand, are wider and without platforms. Powered by oars or outboard motor, they require more water, We have traveled up Darien rivers in both types of craft—and once tipped over in a narrow piragua! Cameras were held high and dry.

Ashore, we hiked in a greenish dusk, surrounded and roofed by a network of creepers, lianas and brush that reached out with thorny branches. Among the trees is the giant bolga with above-ground buttressed roots; another wearing sharp tacks up and down its trunk; the guayacan looking like a huge buttercup; and towering above all, the cuipo sometimes 150 feet tall. Assorted vines entwine to form a ceiling, albeit a leaky one we discovered.

But each tree stood out for its special use to our Choco friends. Pointing them out, El Tigre said, “That one we make piraguas from—and from that we get resin to fill cracks. The light balsa we make into rafts—but that tree makes smokeless fire for tambo. Those palms make thatch roof to last halfa-life; bark from that one makes medicine for shaking sickness (malaria).”

Chocos have a ‘cosmetic’ tree, ochiote, that produces an orange-red seed pod used for body paint. (Achiote may also be in the drugstore lipstick we buy.) Darien jungle is, in fact, the Choco’s drugstore, full of medicinal herbs, barks—and beauty aids such as the wild orchids (and a thousand other flowers) which both men and women wear in their black hair. The combination of tropical temperatures and more than 150 inches of annual rain sometimes turns the jungle into a steamy greenhouse perfumed by flowers.

Contributing to the forest economy are the natural foods: tropical fruits, edible roots and berries, juice of the pipe (green coconut), a good milk substitute. Some of the animals furnish meat. Chocos clear and farm small plots, using sharp machetes.

Most of the Darien animals are non-aggressive except when injured or hungry. The giant tapir, large as a burro and thick as a hog, is good to eat. The jaguar is one of the fiercest, and responsible for the high rate of dropouts from crews surveying the Darien gap for the Pan American Highway. (Ingenious foremen set up record players and blared out rock-and-roll music to frighten the jaguars away!)

There are small, but impressive, jungle residents also: atta, or leaf-cutting ants march in columns carrying leaves over their heads like umbrellas. In underground tunnels they pulverize the leaves for soil on which to grow fungus gardens. Flitting in the air are saucer-sized blue jewels on wing, morph° butterflies. The barefoot Chocos avoid tarantulas and poison snakes.

Because the Choco family group chooses to live in isolation along his river, a problem develops for the young male who is ready to pick a mate. The tribe is well aware that in-family marriage is no way to propagate the tribe and produce strong strains. The boy, therefore, poles his piragua up one river and down another, looking for a girl. Eventually he brings new Choco blood into his group.

Another problem deriving from self-unposed isolation is the distance from a tribal medicine man and conjurer. If there is none within the family, they must wait for one to come past in his boat. He claims to have a jungle cure for everything, even cancer and impotency. (Some of our space-age drugs stern from unlikely sources.) He does get a hallucinatory plant from the forest whose spooky effects greatly add to his prestige. Of course consorting with animistic spirits is a stock-in-trade also. For this, his carved medicine sticks are important. (These are rare museum pieces.)

The medicine man knows enough about anatomy to be able to amputate rather neatly when necessary. We saw a Choco with a stub of an arm. He was injured in a fight, and the hand became gangrenous. A tribal medicine man gave this patient an herb to chew on while he severed the hand at the joint using, of course, his machete. He put something on it to ‘keep the red devils away,’ fastened the skin flap over the stub with wooden pegs. The patient lived to fight again.

When a bright Choco boy wants to become a medicine man, he travels with one as an apprentice. We were told that before he can start practicing, he must kill an acquaintance. So, all his friends and relatives are likely to clear out when they see his boat on the river.

It would be wrong not to mention Chocos’ ethical scruples. In Panama City I kept hearing dire warnings about poison darts, but in the same breath I was assured, “Don’t fear Chocos’ stealing any of your stuff; they won’t touch it, they’re that honest.” We wondered what good our valuables would be if we were pinned with a poison dart.

We discovered it was even difficult to give a Choco something because they think some of the animistic spirits flitting about wouldn’t know it was a gift, but might think they had stolen it. I wore a necklace of small plastic bananas and oranges, which delighted the ladies no end. I used it for a hostess gift, putting it around the neck of El Tigre’s wife. El Tigre insisted she give it back to me. But he finally let her keep it.

A Choco named Zarco agreed to take our astronauts into his jungle and teach them survival. That he did, teaching them how to cook boa constrictor steaks and such helpful tricks. After Pete Conrad (Captain Charles Conrad) made his moon flight, he again met his Choco instructor. Zarco asked him, “Que pasa en la tuna, Pete?” [What’s going on, on the moon?) He indicated it was no surprise to him that man has walked on the moon. Nor did he blink an eye at the $93,000 cost of a space suit—but its weight, 50 pounds, that was something else!–He was comparing it with a Choco G-string for weight, no doubt.

Nor did Zarco want to believe this thing about being weightless in space. The Chocos have no word for gravity, he said, and after alI a man weighs what he weighs! Doesn’t he?

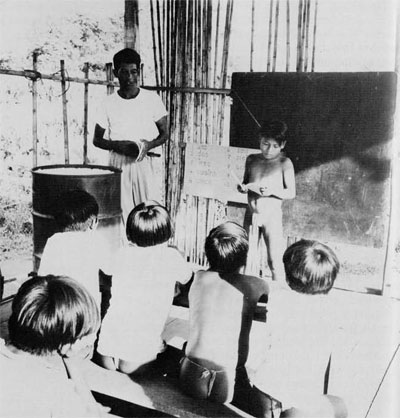

At long last, small schools are penetrating fringes of the Darien. What we choose to call civilization nibbles away at the edges. But most of us would not survive twenty-four hours if we were set down in those jungles. Nevertheless, the Chocos live a fairly affluent life based on the economy of the forests.

The Choco gliding noiselessly through his uncut wilderness is as much a part of it as the sleek ocelot and jaguar, the tangled undergrowth, and the boa constrictor. And if the Choco wore clothes he would seem quite as out of place as would the jaguar if it wore trousers.

El Tigre, as it turned out, is a tribal medicine man and conjurer. He specializes in love potions. As I type this the medicine stick he gave me glares with beady eyes from the corner of my desk. I can tell by the bird he carved on top the miniature head that a strong spirit dwells within. The mahogany head with its beak-like nose and staring eyes reminds me of El Tigre—and I wonder if it is a self-portrait.