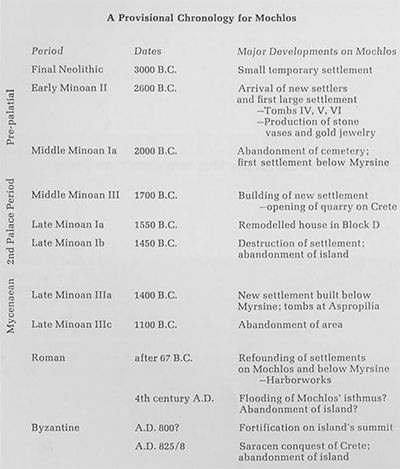

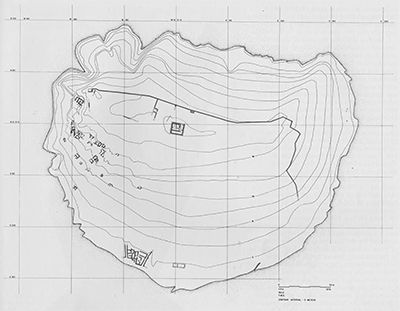

The island of Mochlos, a large outcropping of rock about 350 meters long, rises from the sea just off the north coast of Crete east of the Gulf of Mirabello. It is located in the modern Cretan province of Sitia, and the mountains of the Sitian peninsula ring the island on its south and east, forming a stark backdrop for one approaching by sea from the north. From this side the island is forbidding: its rock sides rise sharply to a height of 45 meters above sea level, and waves break against the projecting rocks with such force that the seafarer must take care. If he steers clear through the shallow straits on the southwest which now separate the island from Crete or successfully maneuvers around the east side of the island, he will find good shelter in the island’s lee. From this side the island appears more promising. Its limestone strata slope down from north to south and, as a result, there is more open space on the south side. It still seems an unlikely spot for habitation, however. There are no trees here, no source of water, and little soil cover; the island supports no animal life today other than a few wild birds and rats. Yet this seemingly barren rock was the location of several settlements in antiquity, and some 4500 years ago in the Pre-palatial age of Bronze Age Crete it was the location of one of the richest settlements in Crete.

Mochlos’ ancient settlements were discovered by Richard Seager, the American archaeologist who excavated on the island in 1908. Seager was one of several archaeologists associated with the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania who worked as pioneer archaeologists in Crete. His first excavation experience was at Gournia with Harriet Boyd Hawes; from there he went on to excavate several important sites in eastern Crete on his own, first Vasiliki which was published with Gournia in 1908, later Pseira and Pachyam mos, both of which were published by the University Museum, and Mochlos, which was in many ways his most important excavation. In 1909, he published the results of his work in the settlement area on Mochlos in the American Journal of Archaeology and in 1912 he published his finds from the cemetery in his Explorations in the Island of Mochlos. His work on Mochlos remains especially valuable for its contribution to our knowledge of Pre-palatial Crete and for illustrating that Crete was already the center of a rich civilization long before palaces were built on the island. In his publications of the site, he concentrated on the small finds from his excavation, as well he might have, since they include the most spectacular objects ever found from Early Bronze Age Crete. His regard for the stratification of finds and his description of the pottery from the excavation were especially important since they confirmed the sequence of Early Minoan II, Early Minoan III and Middle Minoan I already proposed elsewhere. At the same time, Seager tended to neglect architectural description. He often completely ignored the buildings from which the finds came, which were, admittedly, modest by contrast, or else reduced his description of these buildings to a minimum. As a result, our picture of the houses and tombs on the island was confused. In 1971, therefore, while writing my dissertation for the University of Pennsylvania, I decided to return to the island to supplement Seager’s architectural description and to obtain detailed plans of the individual buildings which he had excavated and a map of the entire island, showing the relationship of the cemetery to the settlement. Today, thanks to the cooperation of the Greek Archaeological Service, under whose supervision this project is being carried out, a large part of the work has been completed. In 1976 the Director of Antiquities in eastern Crete.

Dr. Costis Davaras, who has lent his time and support to the project generously, was able to complete the necessary cleaning of the cemetery area which had been excavated by Seager. In the same year a team of architects from Cornell University, Frederick Hemans, Frederick Guthrie and Margaret Denney, was able to complete a topographical map of the island, the first ever made, showing the relationships of the different archaeological remains on the island to one another. Thanks also to a number of other people who have joined me in the backbreaking task of drawing rocks, we have now also completed detailed plans for all the tombs and part of the settlement. As a result of these varied efforts, we have been able to gain much information about the island in addition to what Seager reported, information which would otherwise have been lost, and we have been able to reconstruct the sequence of occupation on the island with more archaeological detail.

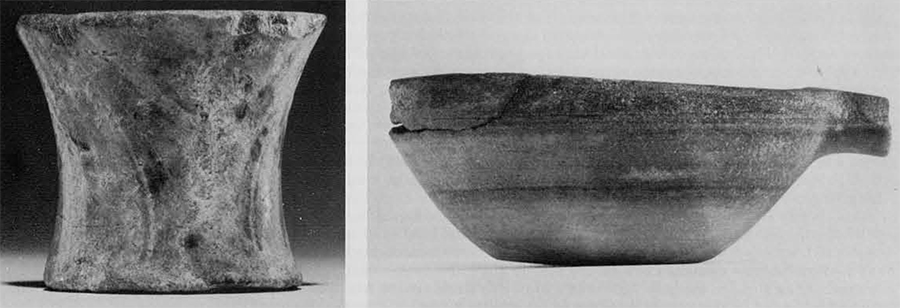

The first settlers arrived on Mochlos around the very beginning of the 3rd millennium. They left few remains, only two small deposits, and their settlement was apparently slight in extent and limited in duration. In the Palace of Minos, Arthur Evans noted certain similarities between the finds in these deposits and those from various Neolithic levels at Knossos, and it seems likely that these first settlers came from the area around Knossos in central Crete, if not Knossos itself. The location of these deposits suggests that the pattern of later occupation on the island was established from the start. The larger deposit was located on the island’s westernmost terrace beneath a later tomb (V) in the same area where a small shrine was located later. It included several block vases and tiny bowls, which may have been used for offerings, as well as a crude terracotta object which appears to be “horns of consecration,” the earliest example known of what was to become a popular Minoan religious symbol. Seager believed the deposit to be votive in nature, and the area may have been used for offerings, if not also burials, from the start. The other deposit, which contained plates, goblets and objects of domestic use, was located in the westernmost part of the area occupied by the later settlement on the south slope of the island, and indicates that this area by the water’s edge was also chosen for habitation by the island’s first settlers.

It is not clear that occupation was continuous into the EM II period since the burnished Pyrgos ware and the painted wares which ordinarily characterize EM I seem to be absent from these early deposits. It may be that as at Magasa near Palaikastro and Sphoungaras near Gournia there was a break in occupation on the site. In any case, at the beginning of EM II, ca. 2600 B.C., a considerable increase in the size of the settlement on Mochlos occurred. Peter Warren, in the report of his recent excavation at Myrtos on the south coast of Crete, has noted the movement of many new settlers into eastern Crete at this time, a migration of peoples from central Crete which Warren suggests may have been caused by overcrowding in that part of the island. These people founded several new settlements in eastern Crete, and the increase in the size of the settlement on Mochlos may have been due to the arrival of such settlers. Mochlos would have offered irresistible attractions. Of first importance to Minoan seafarers would have been the island’s natural harbor. John Leathern and Sinclair Hood, in a report in the Annual of the British School of Archaeology for 1958-1959, have demonstrated that sea level along this part of the Cretan coast has risen 1-1.50 meters since the Roman period; a narrow isthmus, some 150 meters long, now submerged, would therefore have connected Mochlos to Crete in the Bronze Age. This isthmus would have blocked waves in the roughest northwest gale and would have provided ships with excellent harbor on its sheltered eastern side. Another attraction of the site would have been the situation of the south slope itself. Houses erected here would be hidden from ships passing to the north and so naturally protected from passing marauders. The summit of the island offers a far-reaching view out to sea and would have provided an ideal vantage point for espying approaching ships. Finally, the island is provided with two important natural resources. One is the raw material for the stone vase industry which was to play such an important part in Pre-palatial Mochlos. The chlorite schist used for the very first stone vases and the myriad of stones popular in immediately succeeding periods could be found in abundance on the island. The island’s other important resource is the agricultural land which lies across from the island on Crete and stretches several kilometers along the coast to the east. Unlike Mochlos, this small coastal plain is amply watered by springs in the mountains to the south and contains much fertile soil. It is heavily cultivated today and would have supported the population of ancient Mochlos easily.

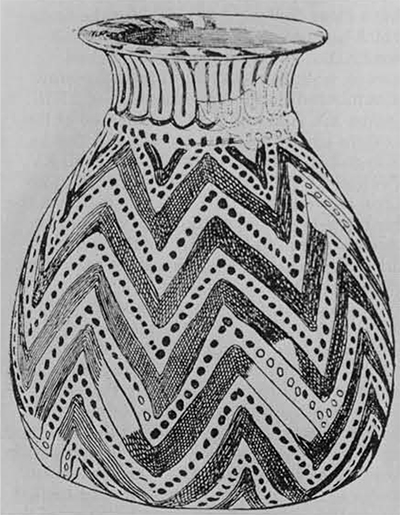

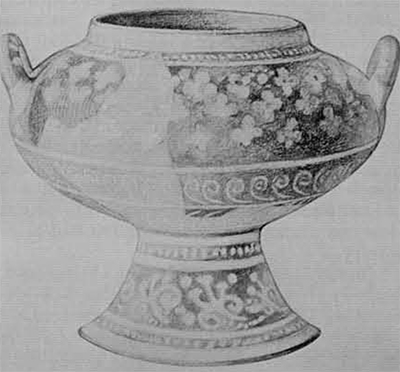

For the next 600 years, the remainder of the Pre-palatial period, Mochlos enjoyed its greatest prosperity. Its stone vase makers were unrivalled masters of their craft, and their highly valued products were exported to other parts of Crete, perhaps even to the Cyclades, Gold workers on the island, working with sheet metal and using only the simplest forms of repoussé decoration, produced diadems, clothing ornaments and a wide range of jewelry which rivalled the treasures of Poliochni and even Troy. The island’s shipbuilders and seafarers were also active. Obsidian chips and cores cover the south slope of the island, including the areas of early occupation, and indicate that Mochlos’ sailors made many trips to the Cyclades to obtain this material. Two silver cups found in EM II/III deposits in the cemetery suggest that they may even have voyaged to Anatolia to obtain these objects, and a Babylonian silver cylinder seal and Egyptian faience beads, also found in early cemetery deposits, suggest contacts even farther afield.

During this time the area of the settlement was considerably enlarged. Seager’s soundings below the Late Minoan houses indicate that the Pre-palatial settlement extended a good 150 meters east-west along the coast and at least 50 meters to the north up the south slope. Recently EM H pottery and traces of walls have been found on the submerged isthmus, and the settlement probably also extended some distance in this direction. Little can be added about the appearance of this early settlement. No description of the early house walls was ever published, and it is not even clear if the EM II settlement possessed a closed settlement plan like those of the nearby settlements at Vasiliki and Myrtos or a plan with open streets and free-standing houses.

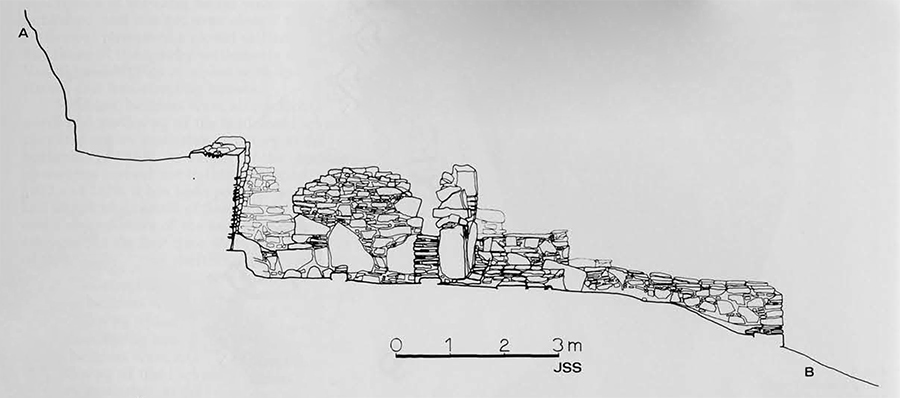

Mochlos’ builders were also active to the north and northwest of the settlement where they laid out an extensive cemetery at the beginning of EM II. As a result of the cleaning operations carried out in this area in 1971, 1.972 and 1976, it has been possible to revise and supplement much of Seager’s description, and a clear picture of the cemetery has emerged for the first time. With the exception of three or four rock shelters, all of the tombs in the cemetery belong to the same type. Although Seager distinguished between larger roofed tombs and smaller unroofed burial enclosures and compared some tombs to Cycladic cist graves, all these tombs are built, free-standing structures which were originally roofed. As Arthur Evans in the Palace of Minos and John Pendlebury in his Archaeology of Crete both noted, the tombs resembled small houses in appearance. They were provided with architectural details such as doors and thresholds, benches, internal partitions, mudbrick superstructures and plastered wall surfaces which suggest that some care was taken in their design. Each tomb was used for collective burials, probably as a family tomb, until the end of the Pre-palatial period.

The tombs are located in three topographically defined areas. Two monumental tombs, one consisting of chambers L II, III and the other of IV, V, VI, are isolated on their own terrace at the westernmost edge of the island. They were larger and designed with more elaborate details than any of the other tombs, perhaps because they were also provided with shrines and may have served a religious function for the community. IV, V, VI is the best preserved. Its walls, built entirely in stone and still preserved to a height of over 2 meters in VI, were constructed in a distinctive manner, characteristic of many of the EM II tomb walls, with large slabs placed upright at the bases of the walls as orthostates. Its different tomb chambers seem to have served different functions. IV served initially simply as an antechamber; perhaps also, as Seager suggested, as a “mortuary chapel” where votives could be deposited. VI was the main burial chamber and deposits made here could accumulate in the deep rock cavity which forms its floor. V was perhaps a later addition to the original “butt and ben” unit IV-VI and served as an ossuary, providing storage space for burials initially made in VI. Chamber VI has been especially important for the rich finds it contained and for the clear stratification of these finds. Seager excavated an EM II a deposit containing stone vases and gold jewelry in the floor cavity and above it a Middle Minoan III/Late Minoan I deposit. In 1971, an EM IIb/III deposit was discovered which had been thrown outside the chamber during one of its periodic cleanings in antiquity, and which contained several objects of considerable value including a one-handled silver cup folded over at the time of its deposit to enclose a small hoard of gold jewelry.

In 1971, an elaborate system of approach, located in front of the tomb complex, was also discovered. It consists of four interrelated elements: a long step running east-west across the west terrace, approximately 4 meters south of the tomb, which forms the base line of the approach; a paved area, lying over 1 meter higher, which runs alongside the tomb’s facade; a raised terrace set against the cliff on the east; and a small rectangular bastion, provided with a step on each side, located at the outer southeast corner of the tomb. Each element uses flat paving slabs of variously colored stones, mostly blue/gray schist, but also black, red and green, which give a bright, decorative effect to the whole area. Presumably, this approach was used for funerary ceremonies, and the raised terrace may have served as a stand for spectators. Fragments of stone vases were found on the top of the corner bastion, and the bastion may have served as a place for offerings.

The largest number of tombs is located in the area adjacent to the west terrace on the south slope of the island. This area is naturally bounded on the west by the sheer rock which drops off to the west terrace and along the east by a line of rock outcroppings running north-south. Nineteen tombs have been cleaned in this area, 18 of which are largely intact. Only a small corner of the other remains, and originally there were probably many more which, as Seager noted, have been “completely destroyed by the process of denudation.” The tombs were built on seven terraces, starting near the water’s edge and running up the hill, with each terrace backing on the one above it. Passages appear to have run lengthwise along the outer side of each terrace, while the individual tombs stood on the inner side, backing against the rise in ground level of the terrace behind, and opening onto the outer passage in front. Many of the tombs can be identified with those which Seager excavated and numbered, so that a clear context now exists for the finds which he published. Seager’s Tombs XIX and XXIII lie on the seventh or topmost terrace, with two plundered (and therefore unnumbered) tombs on either side of XXIII. Tombs XX, XXI and XXII are located at the western end of the sixth terrace and Tombs IX and X at its eastern end. Tombs XIII, XV, XVI and XVII lie on the fifth, terrace, Tomb XI on the fourth terrace, and Tomb VII on the third terrace. There seems to have been no special system to Seager’s numbering, and although most of his tombs can be identified, a few cannot.

In contrast to the large amounts of EM II and EM III pottery which Seager found in the settlement area and the cemetery, he apparently found little MM Ia pottery, and he reported no pottery of the Early Palace period. At this time the eastern edge of the Mochlos plain was inhabited for the first time, and there may have been a shift in population from the island to this area. The reason for such a shift, however, is unclear, and further excavation on the island itself may reveal the missing MM Ib/II remains.

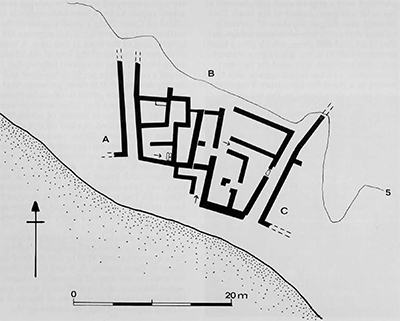

During the Second Palace period, from ca. 1700 B.C. on, the town prospered. Houses were built in the areas on the south slope of the island occupied by the Pre-palatial town; others appear to have been built opposite the island on Crete. Only a small section of the settlement is excavated, but it suggests the general plan of the town at this time. A main street ran east-west at the foot of the island’s south slope. Today this street follows the island’s coast and is partly submerged and largely destroyed. It is clear, however, that sections of it were paved with cobblestones and large slabs and that other sections were rock-cut. A number of streets, of which two have been excavated, opened off this coastal avenue to the north. These were also paved with cobblestones and provided with steps where the slope became steep. The two excavated streets open at the south towards the isthmus which joined Mochlos to Crete, and they may have extended onto the isthmus at this point. The streets apparently divided the town into blocks of houses, and in this respect it would have resembled many contemporary Minoan towns.

Seager excavated four blocks of what he believed to be about 12 houses (extending from approximately W80 to E90 on the Plan). Three of these blocks, A, B and C, lay along the coast to the west of the modern chapel of Agios Nikolaos, and one, Block D, to its east. He also excavated extensions of Blocks B and D lying approximately 100 meters up the slope. In his publication he described only one house, and only part of it, which he believed to be the largest and most important house in the town. This house was located in Block D, and sometime in LM I it was remodelled along more palatial lines. An entrance portico, apparently opening on the main coastal avenue, and a small open court towards the back of the house, perhaps a light well, were added. The main hall was refurbished with a door and pier partition, columns, pilasters and elaborate paving, It was the most luxurious of the excavated houses and may indeed have belonged to a leader of the community.

To date, it has been possible to investigate only one of the blocks excavated by Seeger, Block B. This block fronts on the main street, which runs along the island’s coast today, and is flanked on the east and west by two excavated north-south streets. It remains unexcavated to the north. Seager believed that it consisted of only one house, but actually it is divided into two, one lying to the west and another to the east. The eastern is entered from its side street. Its doorway, set back on the north from the eastern facade of the house, gives access to a large oblong room, in the space to the north of which a stone staircase once led to an upper floor. This house was apparently badly destroyed when Seager excavated, and it is not possible to speculate on the functions of the various rooms. The second house, lying in the western section of Block B, was entered via an L-shaped staircase leading from the coastal street to the upper, second floor of the house. The house contained a good quantity of LM Ia pottery, much of a domestic nature, including numerous strainers, and at least one LM Ib alabastron, probably imported from Knossos. No find spots were recorded, but the location of the entrance suggests that the living quarters were located on the upper floor. The preserved rooms are basement rooms, approached by at least one staircase, perhaps two, from the upper floor, and probably served as storerooms and workrooms. That in the northwest corner of the house is furnished with a fixed stone platform which would have provided a working surface.

The main burials of the Late Bronze Age town have not been found. The island’s inhabitants undoubtedly used rock-cut chamber tombs for their burials, however, and these are probably located across from the island on the slopes of the nearby hills. Some of the island’s residents re-used the early tombs in the Pre-palatial cemetery. in several tombs, including Tomb VI, they cleaned out many of the earlier remains and actually re-used the ancient buildings as tomb chambers. Elsewhere they buried their dead in the ground above ruined and buried tombs. They also used the old cemetery area for infant burials, and in these cases they placed the deceased trussed up inside inverted pithoi.

What was the town’s source of wealth in this period? Its craftsmen no longer produced the gold jewelry for which the island was famous in the Pre-palatial period, and perhaps its source of gold was now exhausted. Some inhabitants continued to manufacture stone vases an unfinished vase was found in Block A), but they no longer produced the large quantity or wide range of stone vases which they had produced earlier. Apparently they could not compete with the palace workshops which were turning out large vases in exotic imported materials. The inhabitants of the island may have contented themselves largely with the everyday pursuits of fishing and farming. The large quantity of strainers found in the western house of Block B suggests, for example, that the occupants of this house were engaged in some such plebeian activity as cheese-making, At the same time, the opening of a stone quarry in a narrow ravine just to the southwest of the island on the Cretan coast would have provided one new industry, and several of the town’s inhabitants may now have been engaged as stone cutters and masons. Large blocks of calcareous sandstone (ammoudha) were cut from this quarry and removed by sea at the quarry’s mouth. The quarry would have provided a fresh source of income to the island, since the stone was a favorite building material in the ashlar facades of palaces and villas throughout Crete at this time and must have been in some demand. It was apparently used only in the remodelled house in Block D on Machlos, and most of it must have been exported.

In the midst of their activities, the inhabitants of the island were suddenly and apparently unexpectedly overwhelmed. Around 1450 B.C. their town was destroyed in a great conflagration, the effects of which Seager noted everywhere in his excavation. Of House D he wrote, “In a number of places in this house were found human bones badly charred, showing that the destruction was no peaceful one, and that many of the inhabitants perished with their houses. The same fact had been already noticed in other houses to the west of the church, and when combined with the signs of fire found in every house would tend to show that the sack of Mochlos was more than usually severe.” Today the destruction of the site is thought to have been caused not by violent attack, hut by the earthquakes associated with the eruption of the volcano on Thera about 130 kilometers to the north of Mochlos in the Cyclades. The earthquakes caused widespread destruction throughout Crete, and the fallout of ash from the volcano, blown in a southeasterly direction by the prevailing winds, blanketed the eastern half of Crete, destroying many crops and making the land impossible to farm. Machias, its adjacent plain, and a large part of Crete were rendered uninhabitable, Those who did not actually perish on the site must have fled by sea, perhaps to the western part of Crete which was largely unaffected, or to the mainland of Greece where Minoan skills were highly valued.

For more than 1000 years the island remained uninhabited. During the Mycenaean occupation of Crete, its harbor may have been used once again, but a site in the hills at the eastern end of the Mochlos plain was chosen for settlement. It was not until the Roman period that a site so close to the sea was again considered safe enough for occupation. By the 2nd century A.D. Machias was again the site of a flourishing settlement. Coins of Hadrian, Diocletian and Constantine were reported by Seager, and Roman pottery of this time may be observed today scattered over the south slope. The Roman town was at least as extensive as the Late Bronze Age town. Because of the rise in sea level which had occurred during the island’s abandonment, the Roman houses were apparently built somewhat farther back from the shoreline than were the Minoan houses, but elsewhere they occupied the same areas and may even have extended farther to the northeast, where they actually reached the east coast of the island. It is likely that the settlement also extended opposite the island on Crete itself, and many of the walls visible here today may belong to the Roman settlement. Just east of the modern fishing village across from Mochlos, Leathern and Hood have discovered Roman fish tanks lying a few meters offshore. Roman houses had been constructed in every area of the settlement which Seager excavated, but during excavation Seager destroyed these in order to reach the lower Minoan levels, so that no further description of the Roman town is possible today.

During the Roman period another settlement was established at the eastern end of the Mochlos plain, and the plain itself must have been extremely productive. It may have produced surplus crops for export. Machlos would still have been the best place along the plain for shipping crops to market although part of its isthmus would now have been submerged. The continually rising sea would have forced the Roman inhabitants to construct harborworks here as they did elsewhere in Crete (including the neighboring Pseira), and the apparent walls tying in the water just south of Blocks A and B, about 15 meters offshore, may have been built at this time to shore up the exposed western side of the isthmus and to provide a waterfront for Roman houses in the area. The main activity in the harbor would have continued to take place on the eastern, sheltered side of the isthmus. The latest Roman finds reported from Machlos are dated to the 4th century A.D. By then or not long afterwards, the rising sea level may have submerged the isthmus to such an extent that Machias could no longer serve as an effective harbor.

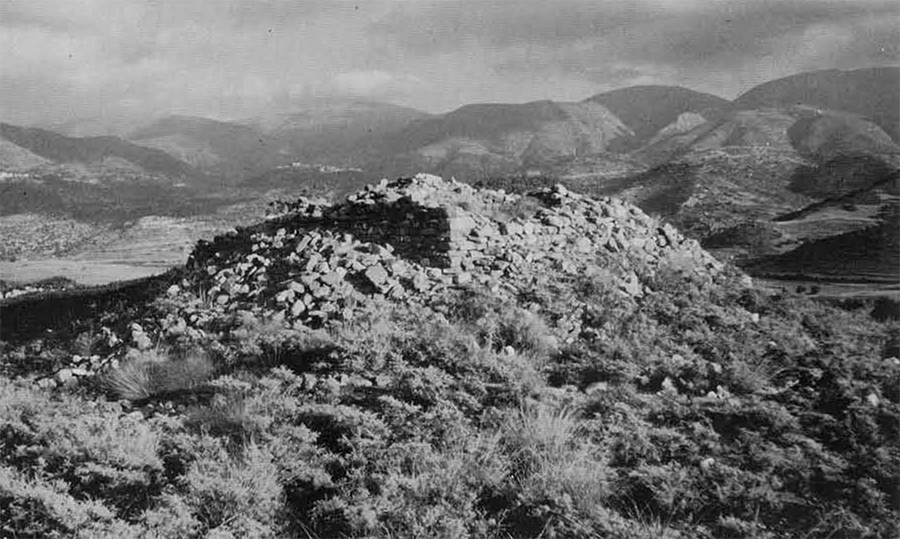

The island does not seem to have continued to be inhabited after its usefulness as a port ceased. The next major building on the island belongs to the Byzantine period, perhaps as Seager suggested to the 9th century A.D. when the Saracenic pirates first made their appearance in Cretan waters.” At this time a large fort was built on the top of the island. It is one of several which were erected along the north coast of eastern Crete to farm a chain of defense for the settlements along the coast. The fort has not been excavated, but sufficient parts survive above ground level to provide a good overall plan. It consisted of a long curtain wall running about 200 meters east-west along the top of the island. The wall was provided with two small towers at each end and with two or more along its length. Side walls joined the upper wall on the east and west. The eastern wall is still preserved and runs southward towards the water’s edge; only a small stretch of the western wall is preserved. The walls are situated strategically in the most advantageous locations where ground level drops off sharply on the outer side, and they appear to have enclosed the highest land area of the island. A number of buildings, perhaps barracks and storerooms, can be made out on the summit of the island. And a large building, approximately 12 meters square, is located in the middle of this area on the highest point of the island. The outer walls of this building, set back on a projecting base, are carefully constructed in stone and are preserved to a height of more than two meters. The entrance appears to have been from the northeast corner, perhaps via a ramp, and the interior of the building is divided into a number of small chambers with rounded walls. One of these was used for a circular staircase, and some of its steps, constructed in cement, remain in situ. The building rose to a considerable height and may have served as a watch tower or light-house from which troops garrisoned in the fort could be alerted of enemy movements by similar forts along the north coast, and from which they could in turn alert the neighboring population on Crete. By A.D. 828 when the Saracens had succeeded in overrunning Crete, the fort was presumably abandoned. After its abandonment, Mochlos was never reinhabited.