Christopher Ray, who for over thirty years created exhibition models for the Penn Museum, died on December 5, 2021. He is fondly remembered for his dedication, intellectual curiosity, perfectionism, and spirited personality. He was unusually talented, to which he added uncommonly high standards. When creating a model he worked with experts, read voraciously on the subject, studied drawings, and questioned every detail, even traveling abroad to see the sites. He donated much of his labor to these projects.

Chris was always a maker of models. Growing up in Westport, CT during the Great Depression, he built his own toys. He was fascinated by astronomy and natural history. With a biology degree from Reed College, he was made curator of natural science at the Everhart Museum in Scranton, where he also led both astronomy and rocket societies. In 1960, he became exhibition preparator at the famed American Museum of Natural History. He later also worked at the Witte Museum in San Antonio, and managed exhibition programs at the University of Minnesota and the Drexel Academy of Natural Sciences, among others. In 1983, he formed his own company, Ray Museum Studios. Over the years, he fashioned exhibitions on prehistoric life, aerospace technology, economics, physics, electricity, ethnology, Egyptian and Chinese culture, and more.

Chris first worked with the Penn Museum in 1980, designing and producing the exhibition The Egyptian Mummy: Secrets and Science. In 1984, he restored the ethnographic model made by Louis Shotridge (see page 8). He built his largest Museum project, the city of Tikal, in 1986. For The Gift of Birds: Featherwork of Native South American Peoples (1991–1995), he built a model of the Sun Temple at Pachacamac, Peru, the site of Museum excavations in 1896–1897. The drawings of his reconstruction were published in Pachacamac: A Reprint of the 1903 Edition by Max Uhle (1991).

Working with David O’Connor and Stacie Olson he made models of two Meroitic (2nd–3rd century CE) mudbrick buildings (a governor’s palace and tomb, found at the site of Karanog, Egypt in 1907) for the exhibition Ancient Nubia: Egypt’s Rival in Africa (1992–1993). In 2003, he created the charming Pompeiian villa for Worlds Intertwined: Etruscans, Greeks and Romans, which is still on display in the Rome Gallery. And in 2009 he made the model of the Death Pit at Ur for the exhibition Iraq’s Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur’s Royal Cemetery.

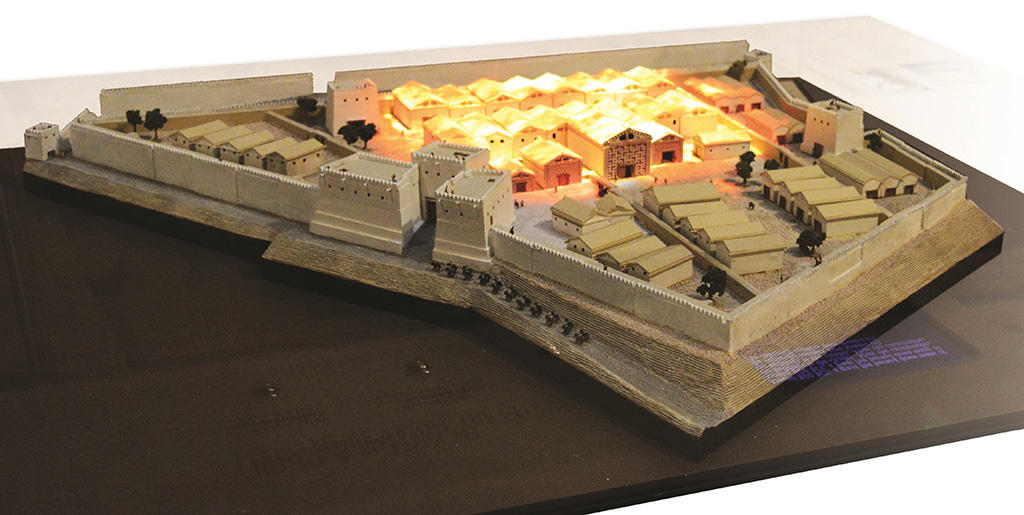

All of Chris’ models were scrupulously crafted to constitute an integral part of an exhibition’s narrative, as with his final and perhaps most challenging creation, the Gordion Citadel reconstruction, created for the 2016 special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas. This broadly themed show highlighted the results of Penn’s longstanding excavations at Gordion, the royal capital of the Iron Age kingdom of Phrygia in central Turkey, ca. 900–600 BCE.

Designing and building detailed, authoritative reconstructions is a complex and time-consuming process, and Chris necessarily worked in liaison with the relevant specialists at the Museum. For his last model he worked closely and continuously with Gordion Archivist and archaeologist Gareth Darbyshire, who provided the necessary excavation data (maps, plans, photographs, articles, background information, and so on), and created the model’s design and scaled plan for Chris to develop; he also conducted ongoing research to resolve the multitude of reconstruction questions that emerged, and contributed to building the model, including painting the finished product. In fact, theirs became a wonderfully symbiotic partnership. Other senior Gordion staff periodically reviewed the model in its various stages, including at a daylong workshop held at the Penn Museum. Like the Tikal model, the Gordion reconstruction took about two years to complete (2014–2016) and would have cost many thousands of dollars if sought from a more commercially minded firm. Yet Chris characteristically and most generously gifted it to the Museum. The satisfaction of supporting educational institutions and reaching out to the broadest possible demographic to educate and inspire people with his lively vision was, for him, its own priceless reward.

The first task for Gordion was to select the model’s theme. A range of options were evaluated, ranging from a single Phrygian monumental building or royal tomb, at one extreme, to the entire city at the other. Eventually it was decided to create a full reconstruction of the main complex inside the high citadel or acropolis at the heart of the city, since this was by far the most extensively excavated and best understood part of the settlement, and its details would convey many of the exhibition’s key concepts. The scale was established at 1:300 (where 1 cm on the model equals 3 meters in real life), since this would provide the optimum size for installing the model in the exhibition gallery yet still convey a wealth of information. The period selected was the late ninth century BCE, the final “Early Phrygian” level, since this was the best preserved of the citadel’s several Phrygian phases. The reason its preservation was unusually good was because an accidental fire had burnt down many of the buildings ca. 800 BCE, after which catastrophe the Phrygians had levelled the remains and dumped a 5m-thick clay layer above, to provide a new surface for rebuilding the complex. The overlying clay protected the burnt buildings from later stone robbing and treasure hunters, and thousands of artifacts survived in situ on the building floors, allowing the Gordion team to reconstruct the form and functions of the buildings to varying degrees of certitude. By contrast, the even grander architecture of the rebuilt level above (“Middle Phrygian” period) was more fragmentarily preserved, and few artifacts were found in situ.

The citadel complex was packed with “megaron” buildings—enormous two-roomed halls—arranged in a number of walled and gated enclosures, all encircled by a defensive perimeter wall, with approach ramps leading up the sides of the acropolis to fortified gates. A stepped “glacis,” or monumental supporting wall, retained the high sides of the citadel mound. The basal courses of the megarons’ walls were made from stones, but the collapsed and decayed remains indicated that the upper fabric was of mudbrick, with complex timber framing for the walls and roofs, the latter clad with clay-covered thatch.

Despite the unusually good preservation of this particular architectural phase, the remains still presented an enormous challenge to a full reconstruction, because only the lower part of the walls survived intact, to a height of around 1 m (ca. 3 feet). The only exception was the citadel’s East Gate bastions, which still stand about 10 m high, but even these apparently lack their upper story or stories. Consequently, a plethora of questions needed to be resolved at every turn, but most pressingly: how high the buildings were originally, what were the roofs like (for example, double-pitched or flat?), what about doors, windows, and decoration? Lack of space here prevents discussion of the myriad problems addressed, but a key breakthrough for reconstructing the megarons was provided primarily by the “Midas Monument”, an enormous Phrygian rock-cut relief located to the west of Gordion (see photo on previous page). This elaborately decorated facade is believed to depict the front of a megaron building, and Darbyshire observed that its width (around 16 m/54 feet) was almost the same as that of Gordion’s largest known building, “Megaron 3.” Concluding that the depiction was probably a 1:1 representation of a real building, about 17 m/55 feet high, the model megarons could be scaled using this as a basic template, and the double-pitched type of roof, the door and window forms, and elaborate geometric decoration, found on this facade or in other similar depictions, were likewise translated to the model versions. In terms of the overall layout of the buildings, the model faithfully replicates the excavated Early Phrygian complex so far as possible. However, in some areas, the excavations have not reached down to this particular level, in which case the overlying Middle Phrygian layout was used as a guide, since this broadly reproduces its Early Phrygian predecessor. Other areas have not been excavated at all, in which case all that could be modelled was an educated guess.

Not everyone is comfortable with such degrees of conjecture or speculation, but these challenges and tensions are in fact a stimulating and ever-present aspect of archaeological interpretation. In any case, it was essential to produce a reconstruction for the exhibition, and the model proved to be a great success, effectively conveying complex archaeological information, and furnishing visitors with an authoritative impression of how the Gordion citadel might have appeared in the late ninth century BCE. The model’s physical presence and charming aesthetic appeal sets it apart from 2D media and digital reconstructions, and visitors could ponder the citadel godlike from virtually any angle. As with Chris’ Pompeiian villa, the experience was augmented by installing the model in a display table that included information text panels, illustrations, and actual artifacts, which highlighted the various types of architectural components and aspects of life in the citadel, as well as the interpretative limitations of the reconstruction. Push button-activated lightshows, with accompanying audio-visual commentary, dramatically spotlighted the conflagration of ca. 800 BCE, as well as buildings of special interest, and indicated which of the structures had actually been discovered by excavation.

This short account can only touch upon Chris’s manifold accomplishments, rarely found skillset, and generosity of spirit, but at least it is a recognition of his significant contributions to the Penn Museum, and knowing and working with him was a truly unique pleasure and a privilege.

Models in the Penn Museum

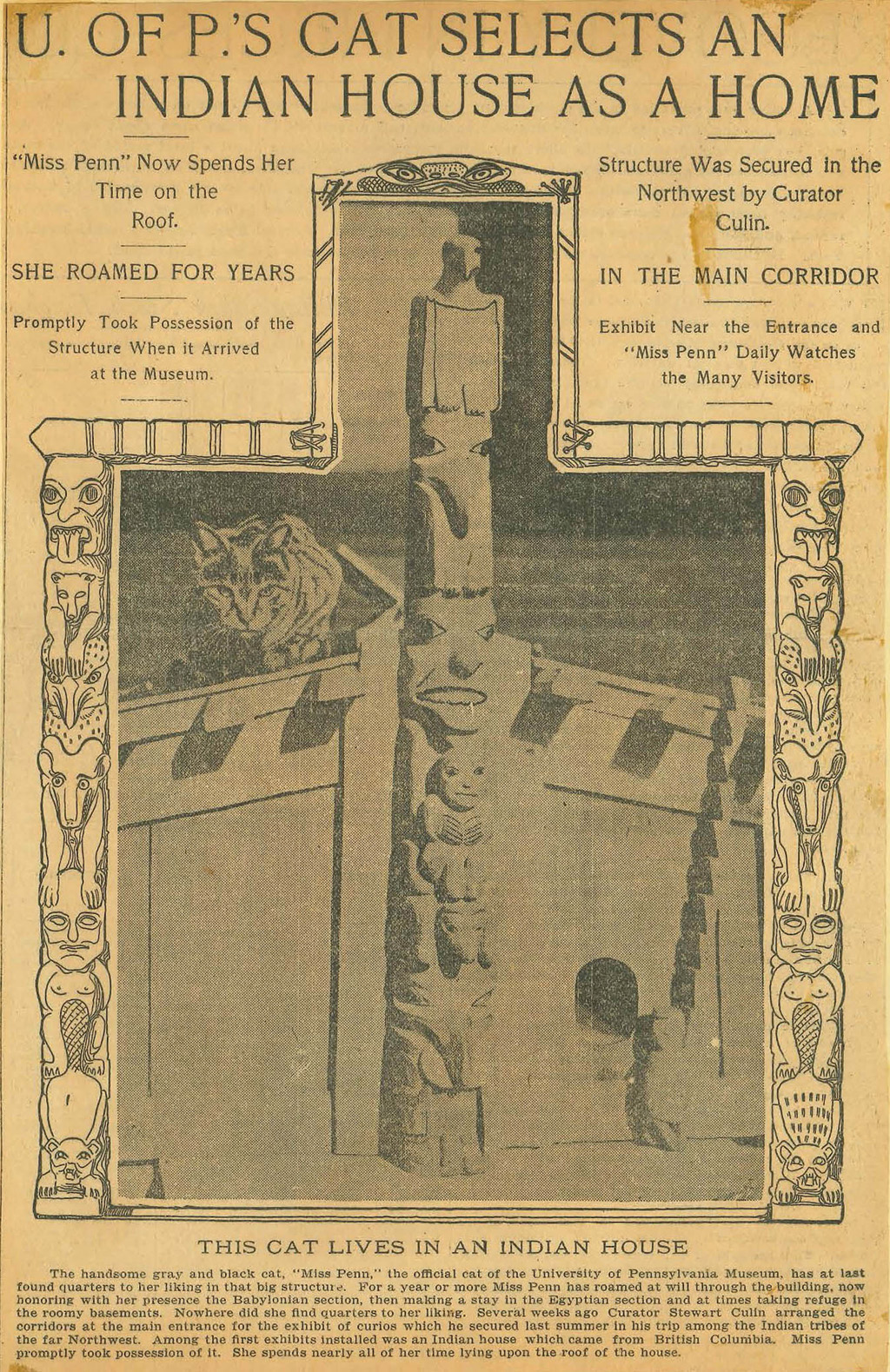

The model of a house in the Haida village of Skidegate, was commissioned for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The model village featured 29 houses and 43 totem poles made by Haida carvers. After the close of the Exposition the Skidegate village model was dispersed and in 1901 the Penn Museum acquired ten of the model houses from the Field Museum.

Louis Shotridge

Louis Shotridge, a Tlingit ethnologist from Southeast Alaska, was hired in 1912. He was a curator, collector, ethnographer, and educator, with many talents (he was also a professional actor and singer). In 1913, he made a model of Klukwan, his native village, which is still on view at the Museum near the East Entrance. The model shows only the central section of Klukwan, which at one time had 65 houses. Although Shotridge had no previous experience building models, he skillfully crafted every detail. It is the first museum model by a Native American curator. Chris Ray rebuilt and restored this model, which was featured in Raven’s Journey: The World of Alaska’s Native People (1986–2010).

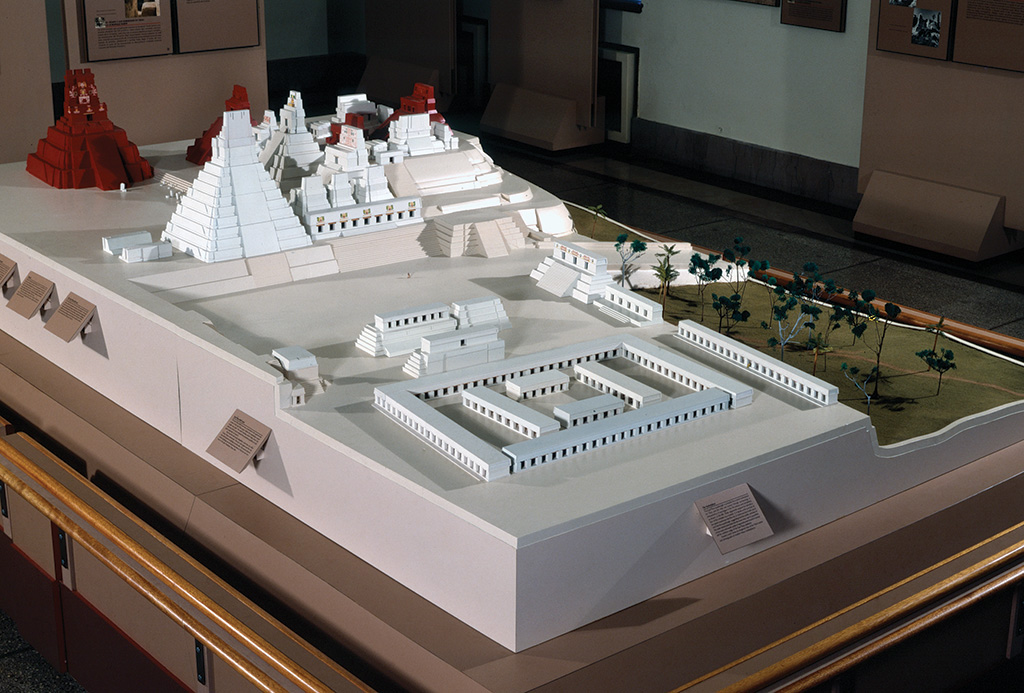

Tikal

Chris Ray’s largest work for the Museum was a 1:100 scale model of the half-mile square portion of central Tikal, Guatemala as it looked at the height of its powers in 800 CE. From 1956 to 1970 the Museum conducted extensive excavations at Tikal, the largest ancient Maya city. The 1986 exhibition Time and Rulers at Tikal: Architectural Sculpture of the Maya was the outgrowth of many years of research on the city’s architecture by William Coe and Christopher Jones.

Chris spent two weeks at Tikal in 1984 before starting the 7½-by-14-feet model, which took almost two years to complete. The numerous temples, ballcourts, markets, and stairs are made of basswood assembled with carpenter’s glue. Buildings were painted and finished to look like plaster. He sculpted basrelief masks and added miniature banana trees to the landscape. He lastly installed 48 miniature stelae.

Chris’s model was the centerpiece of the exhibit since no artifacts from Tikal were in the display. The exhibit was reprised in the 1990s, then the model was sent to Universidad del Valle, Guatemala City.

Gareth Darbyshire is the Gordion Project Archivist and a Research Associate at the Penn Museum; Alessandro Pezzati is Senior Archivist at the Penn Museum.