Travelers who visit the San Blas Islands, just off the Atlantic coast of Panama, are surprised at the high incidence of albinism among Cuna Indians who live there. These white-skinned (or white-to-yellow) individuals stand out like the proverbial sore thumb, among their brown-skinned relatives. The albinos are called Moon-children, on the theory that one or both parents gazed too long at the moon during that particular pregnancy.

We have been told there are about two albinos per one hundred Cunas. This tallies with as authoritative a count as has been made. To get an idea of the significance of so high a percentage, consider the fact that in the U.S.A. albinism occurs in one out of 10,000 births.

Albinos in primitive Cuna society create certain problems among which are: (1) social; (2) health; (3) psychological. As frequent visitors to, and guests of, the Cunas of San Blas we have observed these “white” Indians and their problems.

One of the first tourists to visit the primitive Cuna tribe was Christopher Columbus, when he made his fourth voyage to the New World. The Indians were reported to be savage cannibals numbering some 700,000, and occupied, mainly, a strip of what is now Panama along the Atlantic coast. Since the Cunas knew of certain sources of gold, they fell under the ruthless heel of early fortune seekers, who promptly reduced their number to about 10,000. That remnant took to the mountains, and only during the past century have dared to come down and occupy the off-shore islands.

Since then, the population has jumped to more than 20,000, many of whom still look with suspicion at outsiders. They have been determined to retain their isolation and culture. As late as 1925 they sharpened their machetes and used them on those who dared suggest the women remove their nose rings (symbolic of deep-rooted traditions and religion).

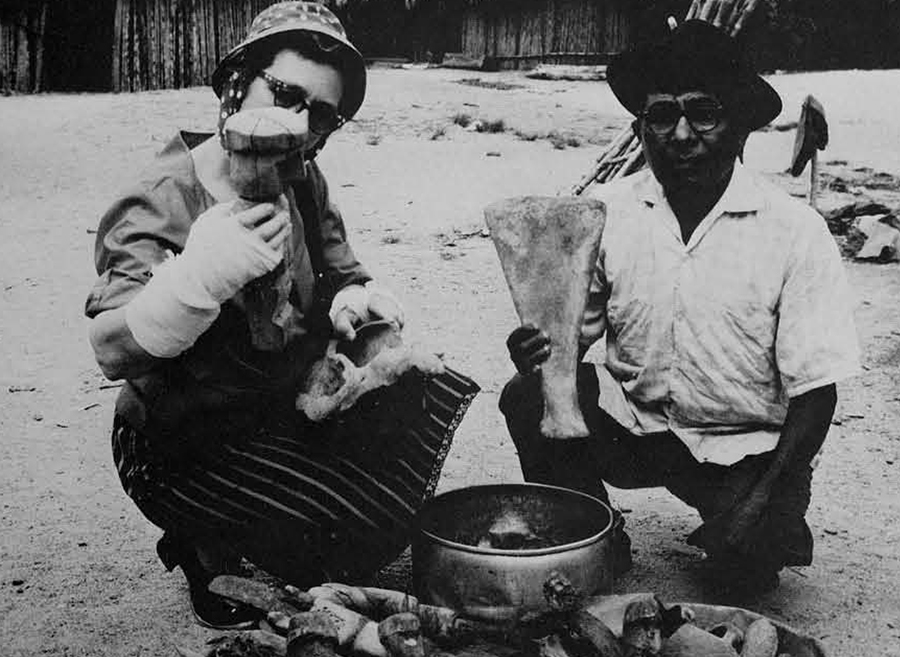

Traditionally, Cuna health has been in the hands of tribal medicine men, who have dealt in herbs and black magic. This remains the situation in general although a handful of progressive Cuna educators dispense certain modern medicines; and find among their patients some of the old medicine men, themselves!

When a woman becomes pregnant, she goes immediately to the medicine man—her first concern being to prevent having a Moon-child. One of the preventive medicines is charcoal, taken internally in large quantities!

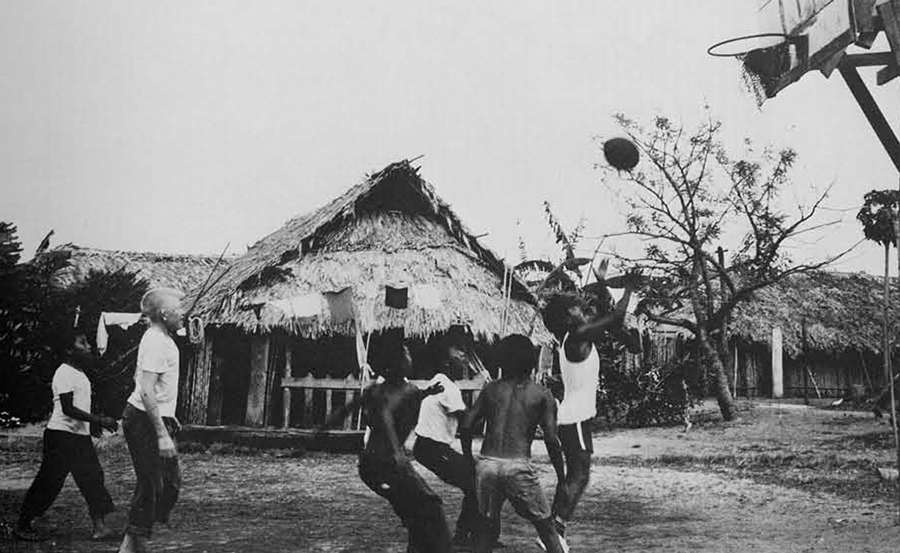

Tribal albinos are not an abused minority group, but it is obvious they have undesirable handicaps. Their non-pigmented skin is subject to irritants of any and all kinds. Scratches and insect bites fester. Intense rays of the tropical sun are almost unbearable, keeping albinos of all ages inside their thatched huts during mid-day. Adults may find this not too heavy a cross to bear, but such confinement gives small children a store of pent-up energy to explode as soon as the late afternoon sun allows. We observed albino youngsters running up and down the clay paths between huts each evening, letting off steam.

One notes that the Cuna albinos are, on the whole, finer boned and less robust looking than their brown-skinned brothers and sisters. The tender skin becomes blotched. The medicine man searches his wares and the mainland jungles for counter irritants, and treats some of the further advanced cases for skin cancer. Because the albinos are less muscular, they are excused from much of the hard work on mainland farm plots and cooperative work projects. They do basket making and other sedentary labor. This pampering of underdeveloped muscles is just what they don’t need, though it shows a sympathetic approach to the albinos’ problems.

Cuna puberty rites, which are sure to be a close forerunner of wedding bells for any brown-skinned girl, mean little to the albino. Albino boys and girls are widely rejected by those of the other sex. Time was when tribal law forbade them to marry. So there have been case histories of few such marriages for researchers to study. In recent years, however, some few albinos have married.

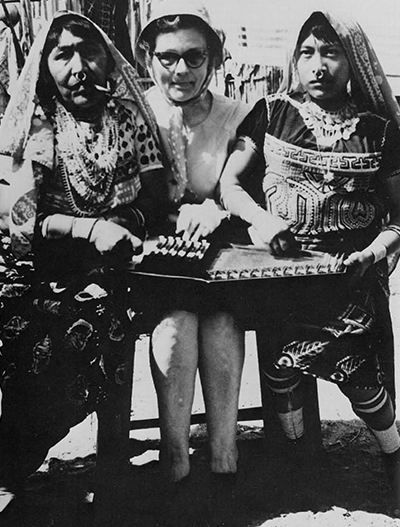

It is plain to see that the gay and jewelled decor, which so delights the Cuna female, is worn by the albinos as well as the darker ones. When a baby girl is newly born, the cartilage of her tiny nose is pierced, for the gold nose ring that is sure to follow. First there is a small ring—which is exchanged for larger and heavier ones as the girl develops. Women wear matching ear plates, large as saucers; also, wide beaded bands around arms and legs. There are many necklaces of beads, animal teeth and coins. The mola blouses, intricate applique done by hand, are a real work of art. The albino girls we saw were not denied all this finery. Of course, the amount worn by anyone depends on family affluence.

It has been thought that the mysterious albinos are closely linked with the spirit world, and that they wield some influence there. The Cunas contend that this is confirmed by the fact that Moon-children sin less than the browns. There may be some foundation for the theory, since aggressive crime and low vitality don’t go hand in hand.

How many newborn albinos have been killed by midwives and buried under the mother’s hammock will never be known. This has been considered an act of mercy, and no questions asked.

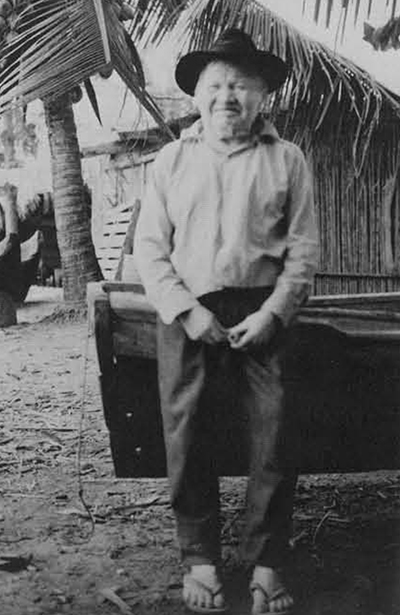

It is not surprising, considering the hostile attitude of some Cunas, that very little albino research has been carried on at San Bias. However, through the years a long-time friend of the Cunas has been Clyde Keeler, a medical geneticist. He has the confidence of the islanders, so has been able to do some research.

In 1963 he brought six Cuna albinos and six browns (for controls) to the United States to undergo various tests. Without going into technical details, the general results were: Average weight of the albinos, almost 10% less than that of the browns. Average height, 3% less than the browns. Eyes of the albinos are myopic, the voice is weaker and has less resonance. The albino skin develops large freckles and sunburn lesions. Continued exposure to sunshine causes hypertrophy of the skin except under the freckles, which are sunken. The albinos lead abnormal lives, restrained in many activities of the culture.

With this as a basis, more information is being added from time to time.

There were more Moon-children at San Blas a decade or two ago because the chief Nele Kantule issued a decree to his people to “keep” the albino babies. Albinos are closer to God, he declared, and on better terms with the divine; consequently they might be in a better position to help the browns spiritually. But since the death of that chief the number of living Moon-children has decreased, partly because of occasional return to infanticidal practices.

Through the centuries the Cunas have remained caught in a pocket of time. But the isolation is now crumbling in spots. Of the 300-plus small islands, some 50 are inhabited. Two of those now have small hotels reached by charter plane from Panama. If you check in one of those hotels you will probably be waited on by some Cuna albino Moon-children.

- The death chant, showing the trip to the spirit world (starting from lower right to upper left).

- Page from the Cuna medicine man’s “prescriptions,” symbolizing very specialized chants for various needs of patients.

- This albino baby has the witch mark from forehead to nose, put there to keep evil spirits of childhood diseases away.

- A natural brown Cuna belle decked out in gold ear “saucers,” nose ring and breastplate—wearing the wealth of the family. She is working on the Cuna art work, exquisite reverse applique with remarkable designs.