Southern Iraq, ancient Sumer and Akkad, is a land of contrasts. Rapid modernization has brought tractors, new crops, and industrial factories. But certain agricultural and irrigation practices, construction techniques, and many other details take one back thousands of years. Change amidst stability, or stability despite change, may be said to characterize not only today, but millennia of Mesopotamian history.

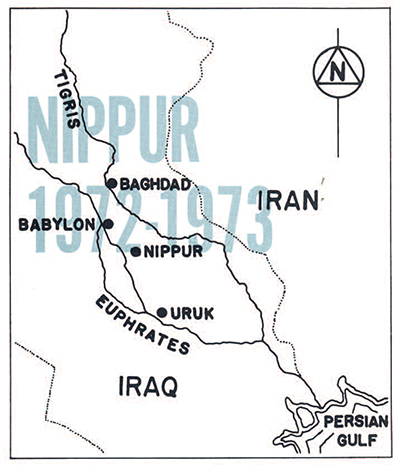

Settlement patterns and land use have been shown by archaeological surface survey to have been tied to shifting watercourses, problems of salinization, depletion of land, and movements of population. Remains of villages, towns and cities lie alongside half-buried ancient canals in the middle of the desert. Some urban centers were important enough to survive longer than most. One such site was Nippur, which came into existence some’ time prior to 4000 B.C. and was not abandoned until about A.D. 1000.

The history of the Nippur region during the past one hundred and twenty years shows how extreme and precipitate changes in local conditions can be.

Around 1850, various British visitors reported that they were obliged to use boats to reach Nippur. The area for miles on all sides was a swamp. We have no indication when the swamp had formed. Slightly later, reports indicate that the swamp was drying up, yet at the time of the University of Pennsylvania Nippur Expedition (1889-1900), the site was still usually approached by boat, though sometimes it could be reached by land.

The gradual shrinking of the swamp has been associated with the deterioration and breakdown of a dam on the Euphrates north of Babylon. A complete rupture of this dam in 1906 left great stretches of southern Iraq, including Nippur, dry for several years. After the First World War, new irrigation controls and dams changed the countryside drastically. By 1926, maps showed a road in the vicinity of Nippur.

In 1948, when the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania reopened Nippur as a joint expedition, the site lay in a sea of sand. Within about forty years, a transition had taken place from swamp to desert.

The sand around Nippur has a certain interest, but the dunes on the mounds themselves, and the recurring sandstorms they imply, make work on the site extremely difficult. However, the sand appears to be moving north and east. When I first saw Nippur in 1964, there was cultivation on only two sides of the mounds. Today, irrigated fields border the site for more than three-quarters of its circumference.

The Nippur season of 1972-73, the eleventh modern season and the fifth in which Chicago has worked alone, had much of change/stability within it. Any archaeological research in Mesopotamia must address itself to cultural change, but it must also be aware of cultural traditions and the thread of history linking periods. Our specific aims in the campaign, however, brought into play other elements of the new and old. With this season, the Oriental Institute was launching a longterm project of research at and around the site. Previous field directors often had to work under the assumption that theirs was the “last season.” The focus of their efforts was, therefore, upon Nippur’s most salient features: the temples that marked the city as the primary religious center in early Mesopotamia; and the “scribal quarter,” or Tablet Hill (see Plan), that has yielded, in thousands of cuneiform tablets, more information on Sumerian history, language, and literature than any other site.

Now that we have a projected program of research, we may turn to other parts of the city and to different problems. For instance, although Pennsylvania, in the last century, traced portions of the city wall, we know little about the outlines of the city and next to nothing about the functions of its various parts, although they have been labelled “Religious Quarter,” “Scribal Quarter,” and “Residential Quarter.” Likewise, we know nothing about the growth of the city, which parts were earlier and which were later, even though previous excavations were extensive. Nippur is a gigantic site, more than three miles around and rising to sixty feet above the present plain level. It will take years of sampling to begin to understand the history of the city; and even then we will be far from the truth.

In deciding to investigate areas of the site untouched in the previous ten Chicago seasons, the West Mound (see Plan) seemed the obvious area to work. This very large mound was relatively ignored by the old excavators, although there are enormous pits in the southernmost tip and in an area that we came to call WA. From examination of surface material it was obvious that much of the mound is covered by an Early Islamic town, and that under that is a mass of Parthian (c. A.D. 100) buildings. There are Parthian constructions on most parts of Nippur, and the size of the buildings, combined with the particular method of deep foundation cuts, makes excavation of earlier, Babylonian and Sumerian, levels difficult and frustrating. One goes to Nippur hoping to reveal more about early Nippur and spends months recording and removing Parthian mud brick. The material from this period is interesting, but the focus of the Oriental Institute is earlier.

Approaching the problem of excavating on the West Mound, one could sink trenches in disturbed localities, but would expend much effort on the later levels. On the other hand, if one takes an area previously worked by Pennsylvania, one must first try to figure out what was found in the 1890’s and then try to link one’s own work with that often inadequately recorded and usually unpublished material.

We decided to use the information given us by J. P. Peters and the other Pennsylvania excavators, and to suffer with old trenches for awhile, in order to avoid Parthian levels and reach early levels in as short a time as possible.

In published and unpublished reports, there is an account of a long trench cut in 1889. This trench ran eastwards from the highest part of the West Mound to the low area called the Shatt an-Nil, which was in ancient times the bed of the Euphrates.

In the long trench Pennsylvania discovered a very large building, or palace, with a central court flanked by baked brick columns. The pillars gave the structure its name, the Columned Hall. West of this building was found an important collection of cuneiform tablets recording the business transactions of the mercantile Murashu family (5th century B.C.). In a tunnel sunk below some rooms of the palace, a few meters west of the Columned Hall, was found another cache of tablets. These were an invaluable group of administrative texts from the time of the Kassites (c. 1300 B.C.), about whom much more needs to be known.

Being interested in the Kassite Period, and in administration, I considered this area the prime candidate for excavation. Knowing that the Columned Hall was Seleucid in date (c. 300 B.C.) and thus earlier than Parthian, and remembering the location as a large pit, we thought that we could reach Kassite levels, and perhaps some administrative building, in this season. However, there was a puzzling inconsistency in the unpublished records concerning the Kassite remains under the Columned Hall. In one place Kassite was said to lie just one meter below the Hall. In another, the depth was given as two meters, and in still another, four. This, we assumed, was the result of an error in recording, or a mistake in identifying levels.

Upon arriving at Nippur in mid-December, 1972, we found that nature was a factor to be taken into account in our operations. The Columned Hall area was, in fact, a large pit, but the exact location of the Kassite administrative archive a bit farther west was under a tremendous sand dune. The best we could do this season was to try to find Kassite levels under the rooms associated with it.

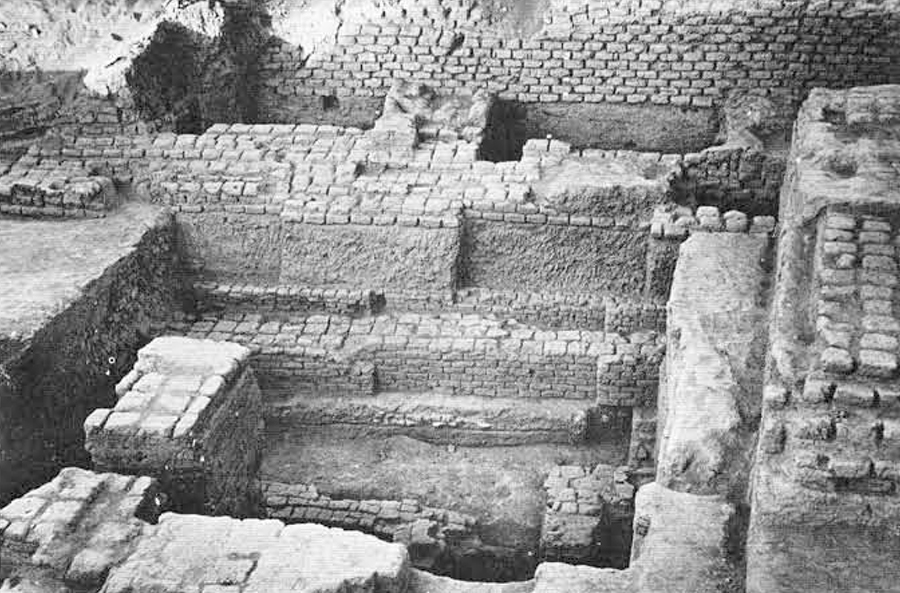

Work began in the Columned Hall area, WA, in late December. Remains of the Hall and related rooms were almost nonexistent. At a slightly lower level, we found earlier Seleucid structures, including a large foundation wall. This wall, which had been cut by Pennsylvania’s long trench, is a corner of a structure that lies mainly to the northeast of our excavation. Our Squares WA 7 and 8, northeast of this wall and inside that structure, consisted of five meters of deliberate fill, most of it Seleucid, some earlier. Digging in these squares was, therefore, fast and relatively free of finds. Squares WA 12-13, southwest of the Seleucid wall, were very different. Just below some Seleucid houses, we were surprised to come upon a small temple, with niches, buttresses, and a recessed entryway. This temple was of rather careless plan; it had no provision for a screened or separated cella, and had been destroyed on the northern end by the Seleucid foundation wall. Another surprise was the finding of an alabaster plaque with an Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription and a figure of Horus holding snakes and scorpions. This object is an amulet to ward off snakes and scorpions. From the pottery in the temple, we could date the building to the Achaemenid Period, a time when Persia had contact with and eventually conquered Egypt.

The levels below the small temple were for weeks a puzzle and frustration. Tamped earth “floors” would suddenly disappear, or be cut by jagged, ancient holes. These holes were often filled with rubbish, brick pieces and many potsherds. After more than a meter, we encountered a wall made of mud bricks of a size so large that the local pickmen thought they were Parthian. No one had ever seen mud bricks this size in a pre-Achaemenid context before. Other bits of mud-brick walling would appear, and seem to relate to nothing. The puzzles finally resolved themselves when, along the southwestern edge of our excavation, we uncovered a series of niched and buttressed walls. These proved to be re-buildings of a temple in the Kassite, Middle Babylonian and Neo-Babylonian Periods (c. 1300-500 B.C.).

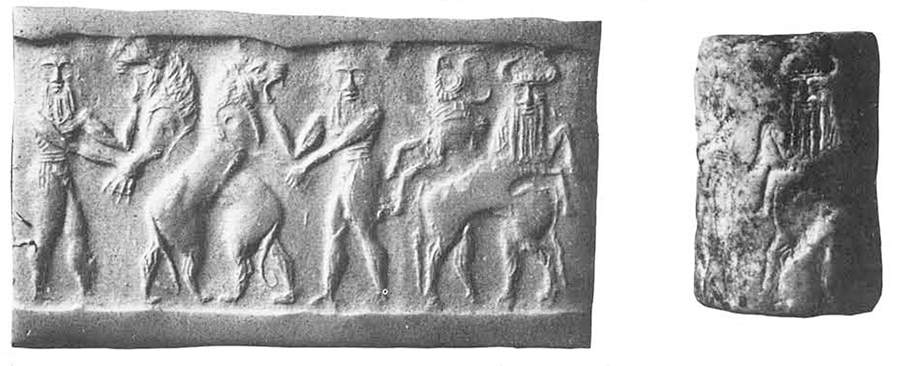

We were able to unearth a length of about twenty meters of the Neo-Babylonian wall to a corner. Inside two small rooms, we were able to excavate below Kassite levels and find evidence of an Old Babylonian version of the building. On an Old Babylonian floor, we found three cylinder seals of Akkadian date (c, 2300 B.C.), and another of Early Dynastic times (c. 2500 B.C.). The seals, in very good condition and of excellent workmanship, must be viewed as heirlooms; so must another stone object, a decorated axe with an incomplete inscription. This last item, inscribed “Property of the goddess Nin- …,” gives us some clue as to the deity to whom the temple belonged. Further work, after removal of the large dune, hopefully will identify the goddess with certainty.

Returning to the area in front and east of the temple walls, we were able to explain the bits of walling, the bad stratification, etc. Study of the sections revealed that this area was, anciently, the slope leading to the river. Erosion, dumping of trash, excavations for mud-brick-making or mortar-mixing, and deliberate leveling to enhance the temple’s surroundings are to be read in the strata. Likewise, the wall with outsized bricks can be explained as a revetment sunk mostly below ground level, and designed to give a stepped appearance to this face of the temple. We have indications of at least two renovations of the stepping.

In this area, the Kassite levels do in fact lie at different depths. In WA 12-13, we found Kassite remains at three and a half and four meters below the Columned Hall. In WA 7-8, on the other side of the Seleucid foundation, however, Kassite remains were found at five and a half meters. As we work west, under the dune, we will probably find Kassite materials at one or two meters below the Columned Hall. The “inconsistency” in the old records was, in fact, an accurate record of remains found on a hillside under the Seleucid

In a gully south of the main operation in WA, we opened a small stratigraphic pit. This operation proved to be extraordinarily productive. Below Seleucid levels, there were two meters of trash pits, dating to Achaemenid and Neo-Babylonian times. Here we found two complete medical commentaries of an ancient scholar who was famous enough to be quoted in tablets found at Uruk, a hundred miles south.

Below the trash pits, were found substantial Neo-Babylonian house walls. We expected then to find Kassite remains, but instead, below a very thin sand lens, we found Old Babylonian (c. 1800 B.C.) and Ur III [c. 2100 B.C.] levels. We then, at a depth of five meters from the top of the pit, began to uncover walls made of plano-convexshaped mud bricks. Such mud bricks are usually the hallmark of the Early Dynastic Period [c. 3000-2350 B.C.). Our two meters depth of walls, with two rebuildings and four associated floors, contained Akkadian material (2350-2200 B.C.). Here were found, besides Akkadian pottery, four Akkadian account tablets, two Akkadian cylinder seals, and a fragment from a brick stamp of NaramSin, a king of the dynasty.

Under the Akkadian levels, we found other plano-convex mud-brick walls along with Early Dynastic pottery types. We had no time to take the pit farther down. It is clear that we have here a rich location for fairly early material. This seems to be a private house area, and is not covered with much late material.

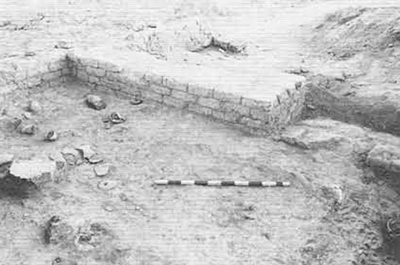

We carried out yet another operation on the West Mound. This was our area WB, toward the southern end of the mound. Here, near the findspot of another cache of Kassite tablets found by Pennsylvania, we chose a location that seemed undisturbed and was covered with Kassite sherds. A little digging made it plain that Pennsylvania had been here before us. The top meter and a half was composed of old trenches and backfill. When we finally reached “good dirt,” we were in Old Babylonian houses. These buildings yielded much information. In one court we discovered many whole or reconstructable pots lying where they had been left in the nineteenth century B.C. Fragments of clay plaques, figurines, and other debris lay in the courtyard. The walls of the building—of baked brick, a rarity in private houses of the Old Babylonian Period—indicated that this building was of more than usual interest. The finding of several cuneiform tablets in the court and in a small adjacent room supported that conclusion. Among the tablets were contracts dated to the 34th and 35th years of Hammurabi, and one dated to the 13th year of Samsuiluna. We thus have about a twenty year bracket (1756-1736 B.C.) for the dating of the house. Also found among the tablets was a literary text in Sumerian.

Below the Old Babylonian level are older, Isin-Larsa, houses. The series of whole and fragmentary pots plus the sherds from WB should help to discriminate Isin-Larsa from Old Babylonian types. This is a range of pottery that is as yet inadequately distinguished.

Probably the greatest importance for future work is the knowledge that the WB area gives excellent opportunities for reaching early levels with little overburden. Our Isin-Larsa levels are about nine meters above plain level. Strata such as those of the Early Dynastic Period, that elsewhere have been found under meters of later debris, or below plain level, may at this spot be found relatively easily.

The final operation for this season was a small pit, SQ, sunk in a low area northwest of the ziggurat in the eastern part of the site. This excavation was carried out by Dr. Peter Mehringer, an earth scientist from Washington State University, in order to sample strata that may give a pollen and faunal record of climate at Nippur over the past few thousand years. Carl Haines, the former director of Nippur, who was with us as a special consultant, remembered that when he made soundings in this locality in 1951-52, he observed a blackish layer about a meter below plain level. He thought that this might be evidence of an ancient swamp. Mehringer found this and another stratum that he thinks were swamp sediments. His analysis and report will appear at a future date.

Looking at the season as a discrete unit of research, we can point to several notable accomplishments. In our main area, WA, we discovered what seems to be a major temple, although we must now try to determine its relation to its surroundings. In the strati-graphic pit, WA 50c, we have, I think, demonstrated conclusively the use of plano-convex mud bricks in the Akkadian Period. Also, we have from this cut a large, well stratified collection of potsherds, including glazed specimens, that will help to set up a better ceramic chronology. The changes in glazes may cause us to reassess our understanding of glazing, especially when detailed chemical and microscopic studies are made. The private house area, WB, has likewise furnished good ceramic criteria from floor levels dated by tablets to distinguish the important Isin-Larsa/Babylonian sequence.

The season must also be viewed as a link with past work at the site, and as the first part of a new program of research. We will continue to work in the trenches opened this year, trying to answer the questions raised. We intend to expand, especially in private house areas, and sample other parts of the West Mound and the plain level around it. Sherds on the plain indicate possible locations of early material without late overburden. In conjunction with such soundings, attempts will be made to trace more of the city wall.

In terms of method, we hope to continue combining old techniques of excavation with new ones, trying to bring in scholars and students from anthropology, paleobotany, and other fields whenever possible. For a site as complex and gigantic as Nippur, we need as much help from various disciplines as we can obtain. Digging merely for objects or for history is no longer justifiable. Piecing together cultural evidence, establishing the historical relevance of an object, a building, or a city, and trying to relate these to environmental or other factors as elements in a larger process are the task of archaeology today. For Mesopotamia, elaborate research designs may be possible. However, it is my opinion that until a firm ceramic sequence is established, such research must be questionable. The main task for the next few years must be the setting up of that sequence, with an eye to future cultural and historical studies. It is our intention at Nippur to be open to new ideas, and try new methods, but to focus on the basic work of good recording and pursuit of a reliable sequence. It may not be as exciting as other programs, but it will be more important..