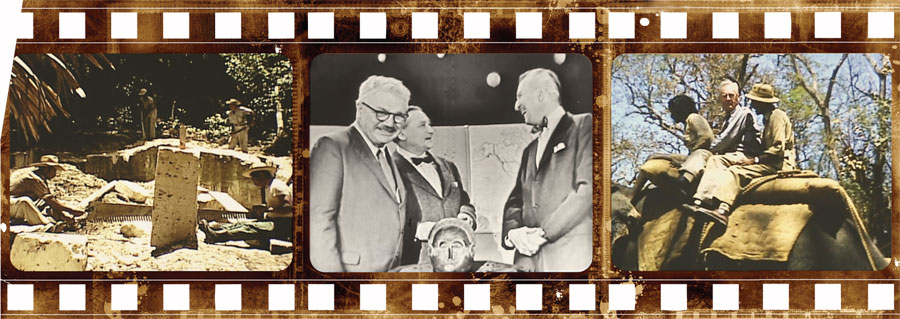

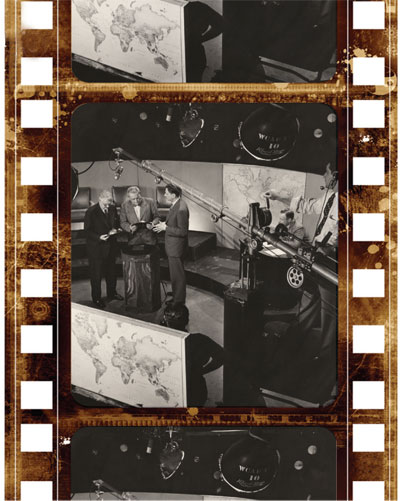

Middle, left to right: Museum Curator Carleton Coon, sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, and actor Vincent Price share a laugh during the recording of the Penn Museum’s television program What in the World?, 1954. Penn Museum, film #F16-4003.

Right, Watson Kintner rides an elephant in India, 1959. Penn Museum, film #F16-0171.

The pervasiveness of moving images in human communication today is indisputable. Film and video fill our theater, television, and computer screens. It is rare, however, to see in this mix a collection of travel films from all over the world, dating back to the 1920s. Through a partnership with the Internet Archive, the Penn Museum is showcasing its spectacular collection of hundreds of archaeological films and travelogues online (http://www.archive.org/details/ UPMAA_films).

Since the introduction of film in the 1880s, through the golden age of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s, and into the modern world of television and the Internet, the appetite for moving images has been insatiable. Like its predecessor, photography, invented in 1839, moving images immediately captured public attention. One really could tell stories with pictures. Although the rewards of film are considerable, the technical difficulties and high cost of crew and production have always made it a more problematic medium than still photography, all of which is multiplied when filming on location.

If it were not enough trouble to make a film, it has proved even more difficult to preserve it through time. Due to the disintegrating (or combusting) film base and the carelessness of producers, a large part of the world’s moving picture heritage has not survived. Today, the collections of motion picture film that do exist are difficult to use and often too fragile to screen.

It is therefore a happy circumstance to discover the Penn Museum’s large, well-preserved collection of 16mm film footage of impressive geographical scope, dating from the 1920s to the early 1970s. Until recently, the collection was too difficult to view to even catalog. The rarity of this material combined with its inaccessibility would have made it a loss to culture were it not for the Internet. Now hundreds of reels can be viewed and enjoyed any place with an Internet connection.

The 675 reels of 16mm film are simply too much material for casual browsing. Spending time with the films, however, is worth it. Comprised mostly of travelogues and museum research footage, but also including episodes of the Peabody Award winning television quiz show What in the World?, the collection will absorb you. Most of the films are silent unedited footage taken by amateur filmmakers, yet the richness of the material easily compensates for the lack of craft. Outstanding among these is an early film on the Catawba and Cherokee by Frank G. Speck, the founder of the anthropology department at Penn, as well as Excavation at the Site of Seneferu’s Pyramid, chronicling the Museum’s work at Meydum, Egypt in 1929–1930. Lowell Thomas, the famous news broadcaster who made Lawrence of Arabia famous, narrated several films on the Museum’s work in Brazil and Iran. Films document Penn’s celebrated excavations at Tikal, Guatemala, and Gordion, Turkey, including the opening of the so-called King Midas tomb at Gordion in 1957. For a fascinating early look at the Penn Museum see Ancient Earth: Making History Everlasting (1940), as well as a more contemporary view in Search (1974).

The travelogues, however, offer the richest source for the online explorer. From the 1939 New York World’s Fair to Dwight Eisenhower’s 1946 visit to Brazil, from the training of elephants in India to demonstrations of the lost-wax casting process in Ethiopia, the range of subjects is staggering. The viewer can also see the earliest color footage of Machu Picchu (1950), pearl cultivation in Japan (1965), or a mongoose and a cobra fighting for their lives (India, 1959). Wherever one chooses to go, the film collection on the Internet Archive offers a trip back in time, sideways around the globe, with unexpected turns, but without the fear of getting lost.

What in the World?

Beginning in 1951, and running on and off until 1966, the Penn Museum had its own television show called What in the World? A coproduction with WCAU studios in Philadelphia, and syndicated nationwide, it was one of the first television quiz shows, featuring three scholars whose task was to identify archaeological and anthropological artifacts from the Museum’s storerooms on live television. In 1952, the show garnered an early Peabody Award, television’s most coveted honor, “for superb blending of the academic and the entertaining.” And though never a great commercial success, fan devotion was high, and constant letters to the producers kept the show in business. The show inspired imitators, including Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? hosted by the legendary archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler on BBC.

Created and moderated by Froelich Rainey, Museum Director from 1947 to 1976, What in the World? provided inspiration for budding archaeologists around the country and proved that television programming could “be popular without being condescending.” Emerging through a cloud of smoke, the artifact was identified for the audience, who then watched the panelists, more by means of collaboration than competition, determine its use and origin. The panel, which included two Museum curators and one guest scholar “offered a gentle reminder that scholars can be folksy and funny as well as formidable,” in the words of Life magazine (December 17, 1951).

Early television shows survive today as Kinescopes, recordings of a television program made by filming the picture from a video monitor. Kinescopes were intended to be used for immediate rebroadcast or for an occasional repeat of a prerecorded program, but were not normally saved by the studios. Thus, most early television shows are represented today by only a handful of episodes, which is true also of What in the World? Only five episodes of the program exist, though one of these features the famous American actor Vincent Price (1911–1993) as the special guest.

Watson Kinter

The largest collection of travelogues is that of Watson Kintner (1890–1979), a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania with a degree in chemical engineering. Kintner worked for Radio Corporation of America (RCA) until his retirement, where he was an early pioneer in the standardization of the vacuum tube. A man of means, he traveled to more than 30 individual nations over a period of 36 years, from 1933 until 1969. Kintner visited places such as Mexico (where he filmed painter Diego Rivera), Guatemala, Ecuador, Morocco, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Australia, Iran, and Ethiopia. Presumably Kintner’s travels were planned for pleasure, though he chose to document each of them on 16mm film, 408 reels in all.

On his travels Kintner largely avoided the obvious tourist destinations. He instead recorded daily life and work among the people he visited, including their handicrafts, home industries, dwellings, household arrangements, dress and adornments, agricultural techniques and equipment, and local commerce. He also filmed sites of archaeological interest and museums. For the first three years of his travels he filmed in black- and-white. In 1936, when Eastman Kodak introduced the color stock Kodachrome (a highly stable and color-accurate film), he began to photograph exclusively in color. Kintner also took notes and kept material related to his trips, including financial records, correspondence, and maps.

Kintner took photography very seriously as a discipline that should be applied to field work, and in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he funded weekend seminars for University of Pennsylvania graduate students, taught by Life magazine photographers. Upon his death, Kintner also left an endowment to fund various museum activities and programs. The Penn Museum is indebted to Kintner for his farsightedness in documenting his travels on film and for bequeathing his collection to the institution.