The excavations of the Peabody Museum of Yale University and the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania entered their second season at the end of January, 1962. The expenses were again borne by the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Fund of the University Museum and a grant from the Bollingen Foundation of New York, established by Mr. Paul Mellon, to Yale University. The scope of the project has been materially increased through an agreement between the expedition and the Department of State. Under the terms of the grant agreement, the considerable expenses for labor, local transportation, boat rental, and the provisioning of the camp sites were met through Public Law 480 funds. These funds are generated in Egypt through the sale of American agriculture surplus to the United Arab Republic. Their availability to American universities for archaeological research has been made possible by the administration’s favorable response to the UNESCO plea for the salvage of the Nubian sites and through Congressional action.

The staff for this year’s work consisted of the author as director, Nicholas B. Millet of the American Research Center in Egypt as assistant director, Alexander H. Jeffries Jr. (Pennsylvania) and Peter Mayer (Yale) as architects, Alan R. Schulman (Pennsylvania) and Bruce G. Trigger (Yale), both graduate students serving as archaeological assistants, James Delmege (Pennsylvania) as photographer, Hubert Queloz of La Chaux de Fonds (Switzerland) as draughtsman, and Farouk Gomaa, inspector of the Antiquities Department. At the beginning of the season we were fortunate in having M. Henri Wild of the French Archaeological Institute as our guest, and he kindly contributed a fine copy of the damaged paintings of the tomb of Hekanefer.

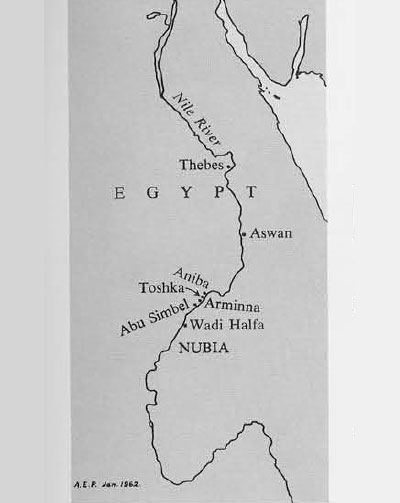

Across the river from this important rock tomb, described in a previous issue of Expedition, is the winter landing place at Toshka West for the post boat, the steamer which makes a weekly round trip between Aswan in the north and Wadi Halfa across the border in the Sudan. In ancient times, diorite, carnelian, and amethyst were quarried some fifty miles west of Toshka in the waterless desert. These quarries were rediscovered in the 1930’s and proved to have been the source for the diorite used in the statues of Chephren, the builder of the second pyramid of Giza. Stelae at the site also attested to their exploitation into the Middle Kingdom, particularly in Dynasty XII. Although a series of intervisible cairns, one with a message box, marked the route between the quarries and the river, the terminal point on the river where the stone was loaded for its northward journey was never found.

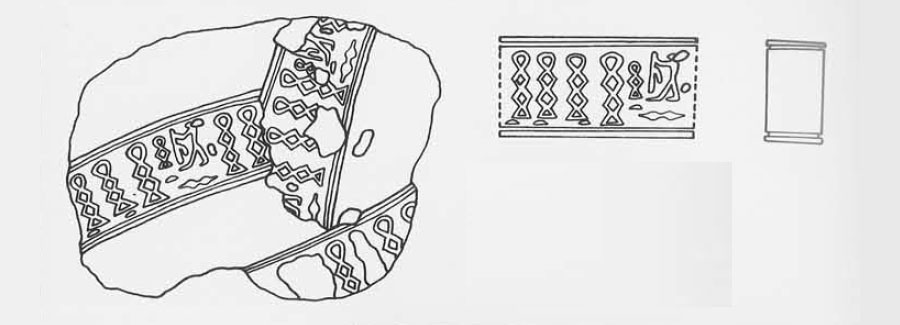

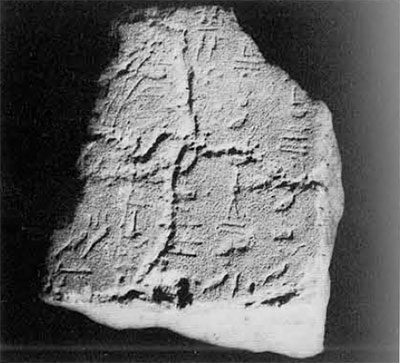

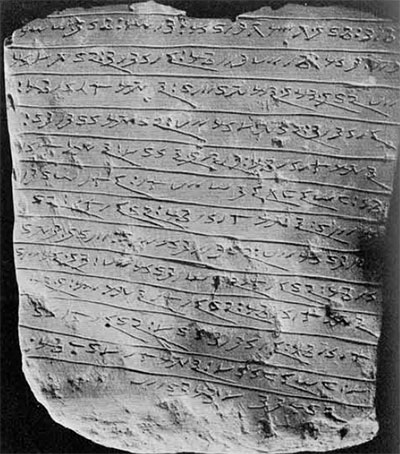

In view of objects found during our excavations near the modern boat station, we are confident that we have now discovered at least one of the embarkation points. The earliest indication is a mud jar stopper with impressions of a cylinder seal of the archaic period. It was found in a grave in a cemetery overlooking the station. The sealing consists of the name ht written several times and a group perhaps to be read as hwsi, with the possible meaning, “builder.” The name is attested at the outset of Dynasty I in sealings of the reign of Hor Aha from Sakkara, Nekada, and Abydos, and on a bowl of volcanic ash of unknown provenance datable to the first half of the same dynasty. Although our seal impression is not dated in a specific reign, it may well belong to the reign of King Aha and may consequently be the earliest dynastic record in Nubia. In the reigh of Djer, the successor of King Aha, a battle commemorated on a rock near Wadi Halfa shows that the influence of these early kings extended as far south as the second cataract. The second indication of the ancient prominence of Toshka is a battered fragment of an Old Kingdom inscription with the traditional statement of the expedition leader, “I brought all good products which are brought therefrom.” The significance of the text lies in the identification of Toshka, with the ancient place name cited in the inscription, Satju. The stone was re-used in the building of a modern waterwheel, where it was found by our first year’s architect, Anthony Casendino. The third piece of evidence is a sandstone stela of Year 4 of King Amenemhet II of Dynasty XII (1927 B.C.) with the text: “There came the herald Horemhet to fetch mhn(m)t(?)-stone. The number of his expeditionary force was […] guardsmen, 20 chamber officials, 50 lapidaries, 200 stone-cutters, 1006 workmen, and 1000 asses.” The stone mentioned is probably either jasper or carnelian. The stela was discovered by an old farmer named Dhahab Gomaa while working in the fields now under water during most of the year.

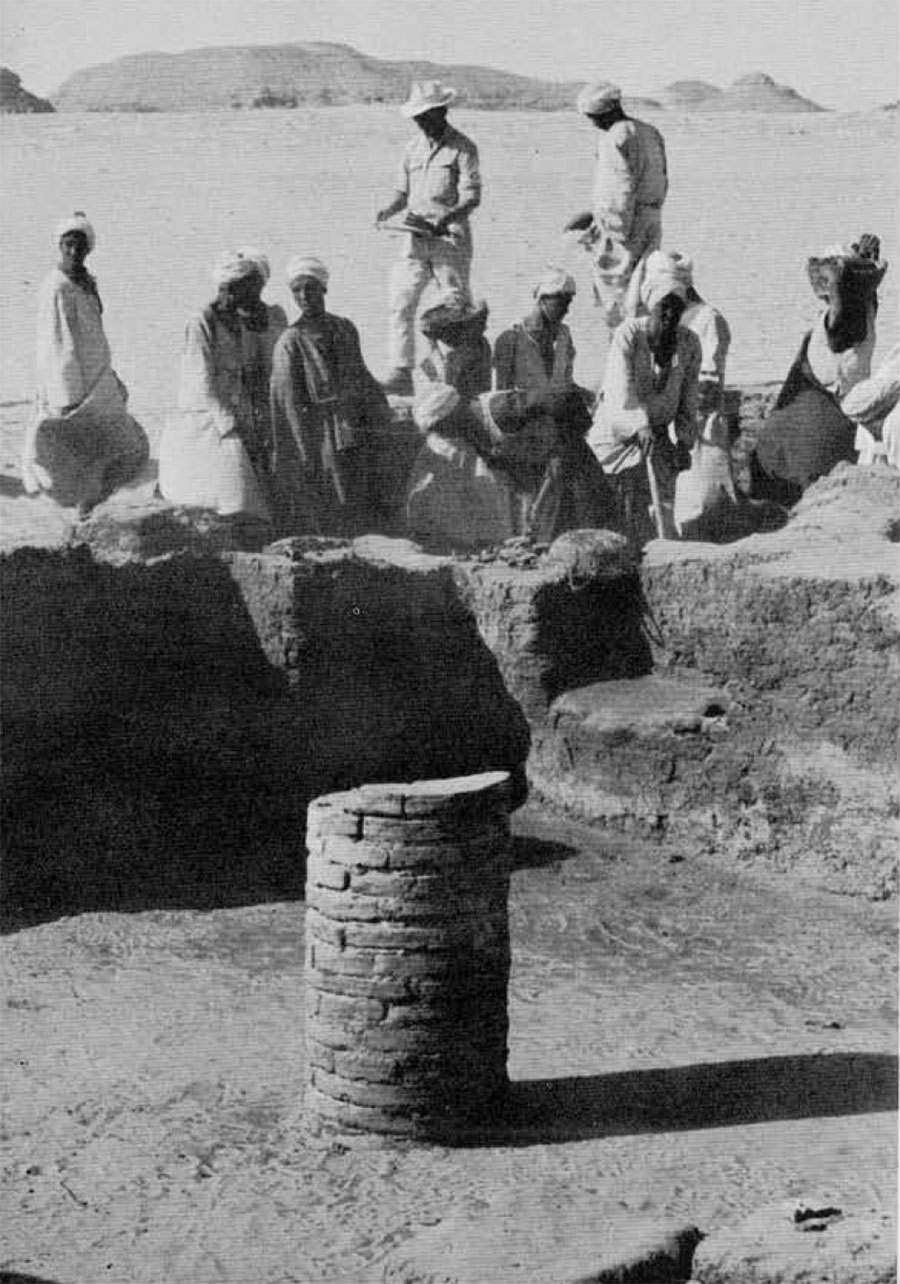

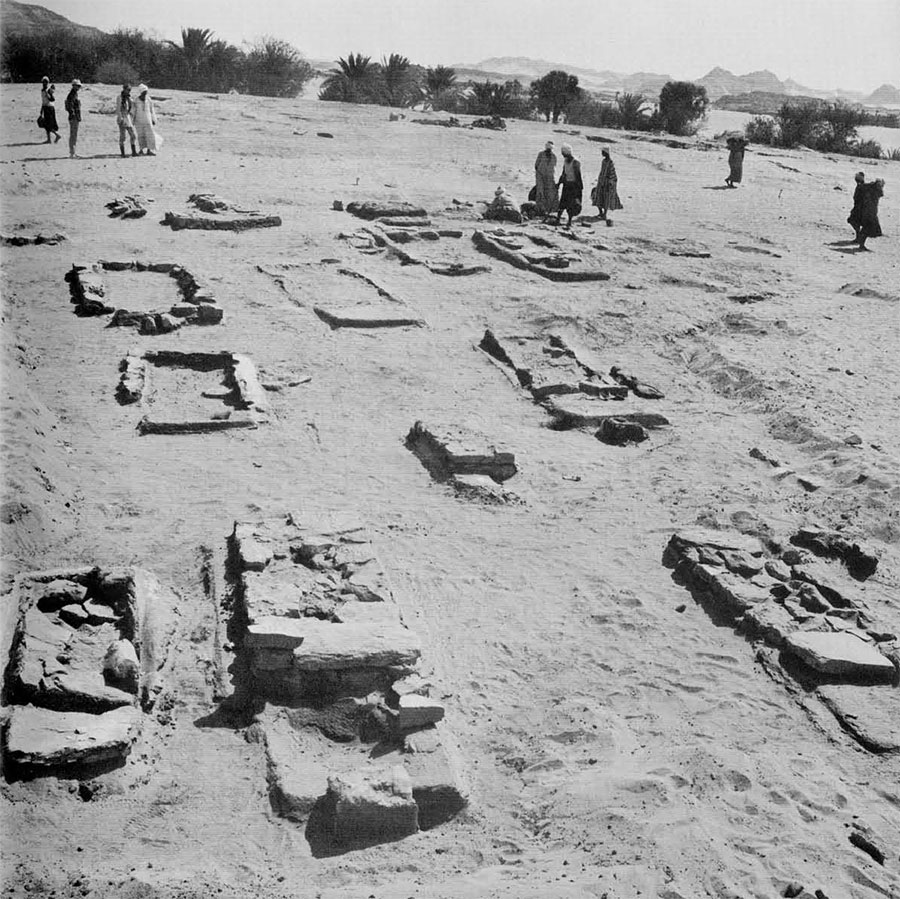

Fortunate as we were to find these indications of the ancient exploitation of the area, or own work lay in the excavation of an extensive cemetery by the river bank, an earlier cemetery on the hill overlooking the station, and a small Meroitic house on the edge of the desert, this last perhaps the house of the cemetery watchman. During the 1961 season some 60 tombs were excavated at this point, while by the end of the 1962 season the number exceeded 200. The tombs nearest the river bank were on the Meroitic period, mainly in the first, second, and early third centuries A.D., when Egypt to the north was under Roman domination. The cemetery was extended in the following X-Group period at a higher leve, and finally in Christian times the reverse slope of the hill was used for Coptic tombs.

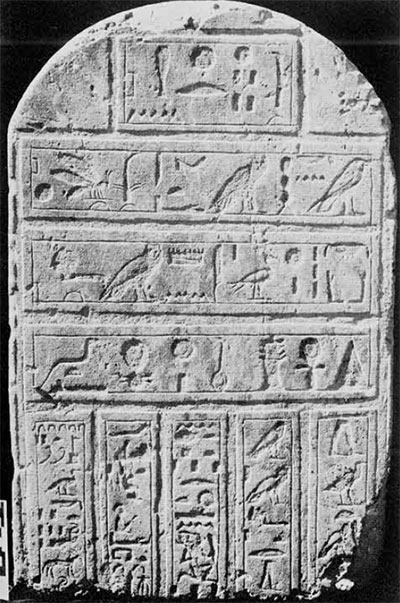

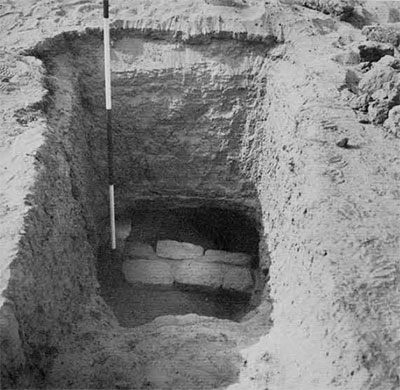

The greater part of the Meroitic cemetery lies under water during the winter. The superstructures of the tombs had been completely razed at an early date when the entire cemetery was ransacked and plundered. Yet careful excavation yielded considerable information about the cemetery and its burial equipment. of particular interest was the difference noted in the characteristic Meroitic and X-Group tomb types. The former generally consisted of a short inclined ramp leading away from the river to a small burial chamber hollowed out of the ground for a single or multiple burial, the bodies lying from east to west. The latter consisted of deeper trench-pits the long side parallel to the river, with a niche along the west side at the base for burials lying from north to south. In both types the burial was sealed off from the ramp or pit by a brick, stone, or brick and stone blocking. In the Coptic graves to the west the traces of the lower part of the superstructure showed them to have been of the same type recorded by Monneret de Villard at er-Rammal to the south. In some cases the burial and the superstructure connected with it were out of alignment, indicating that a period of time was allowed to elapse between the settling of the earth and the erection of the simple white-washed superstructure. As a regular feature a small niche of a few bricks or stones was built on the west side at ground level for a lamp. Several of these niches with their lamps still in position were found, and in each case they were sheltered from the north winds. The main discovery in this area, however, was a fine Meroitic tomb stela, which was apparently taken from the adjacent Meroitic tombs for use as a building stone in a Coptic grave.

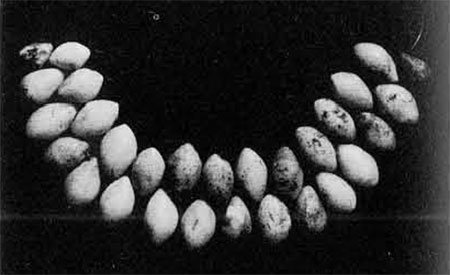

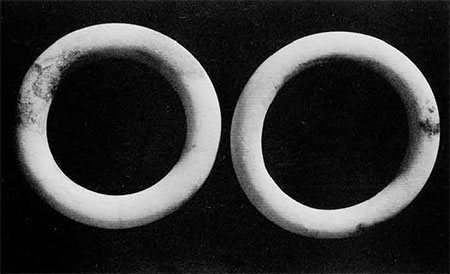

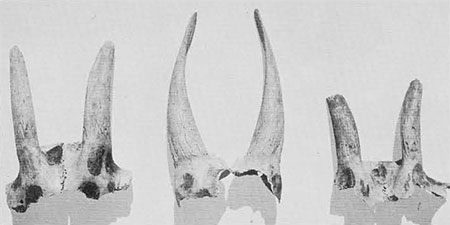

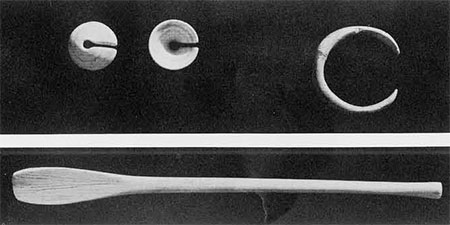

A new phase upon which we embarked during our second season was the excavation of two cemeteries of the C-Group period, the phase of Nubian occupation corresponding to the Middle Kingdom in Egypt proper (about 1900-1700 B.C.). Unlike the later tombs examined, the burials were placed in a pit, the pit filled with earth, and then a small tumulus erected with a circular stone retaining wall. The type, which is well known, is generally found completely plundered, but occasionally the fine incised pottery deposited outside the stone rings is preserved. In our area, almost all the stone had been removed for building and with it the pottery. Several burials, their location long concealed by this loss of the superstructure, were surprisingly intact. Of the two illustrated, Toshka West Cemetery C No. 76 is a burial of a woman with a copper mirror by her head, four ivory rings on the left hand, a necklace of mottled stone and faience beads, and triple-strand anklets of ostrich egg-shell beads; traces of a leather garment were also observed. The other, Toshka West Cemetery C No. 93, is also the burial of a woman. A copper mirror lay beneath her left elbow, eleven seashell bracelets on the left lower arm, a bracelet of carnelian barrel beads on the right wrist, anklets of carnelian and cowrie shell on the ankles, a copper rod near the hands, and a small copper scorpion, perhaps part of a pin, also near the hands.

Objects of particular interest from the other burials in the same cemetery, in which we excavated 103 graves, include a large series of necklaces, bracelets, and anklets of beads of various materials, a pair of attractive alabaster armlets, a pair of heavy ivory armlets, an ivory spoon in excellent preservation, a pair of shell hair-rings, and a feather pillow.

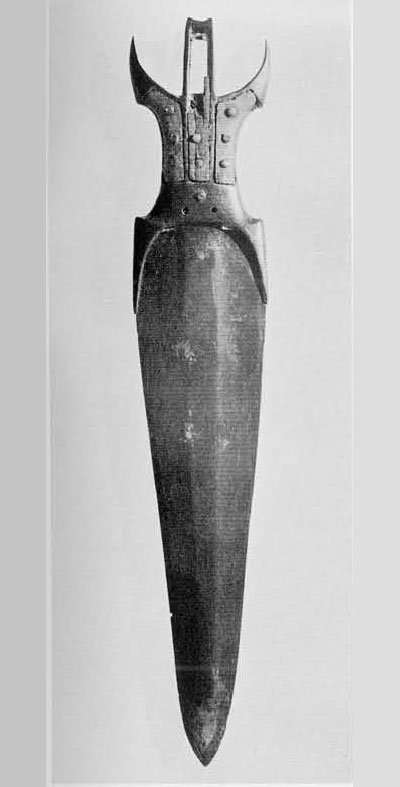

On the desert ridge just south of this C-Group cemetery was a burial ground of a different group of about the same period. These ancient Nubians are called the pan-grave people after the shallow pan-like graves they built. The hieroglyphs on a scarab and on an incised bead probably reflect, respectively, the names of King Sesostris I and Sesostris II of Dynasty XII; and the occurrence of painted animal skulls as offerings is typical of the pan-grave people. In the largest of the tombs, which was in a circular form, the splendid bronze dagger illustrated in these pages was found.

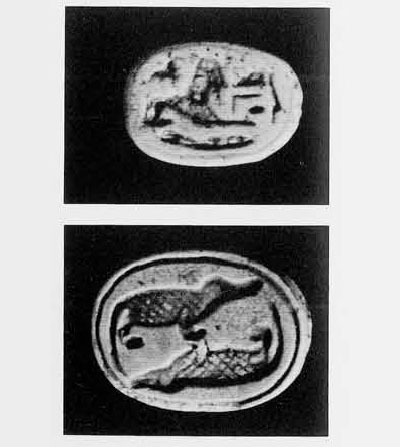

Work was also continued to the south at Arminna. On the east bank a large plundered tomb of early Dynasty XVIII was cleared. In addition to a considerable amount of broken pottery, including a small rhyton or funnel of Aegean inspiration, three scarabs were recovered, one bearing the representation of two crocodiles and another a sphinx. On the same bank PEter Mayer, expedition architect, came upon a previously unknown rock text consisting of the cartouches of King Kamose followed by the name of the king’s son Teti, and immediately beneath it the cartouche of King Ahmose, his brother and successor, who is considered the first ruler of Dynasty XVIII, followed by the name of the king’s son Djehuty. Many years ago another text of these kings had been found in the immediate vicinity, but the present text was overlooked. Two cartouches of the problematic King Kakare were also found. He appears to have been a local ruler independent of Egypt, since his name is found only in Nubia.

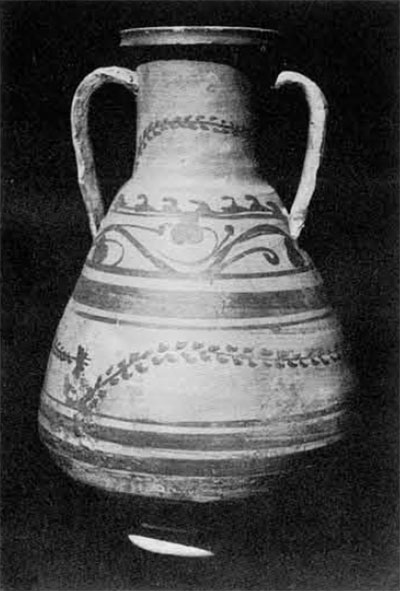

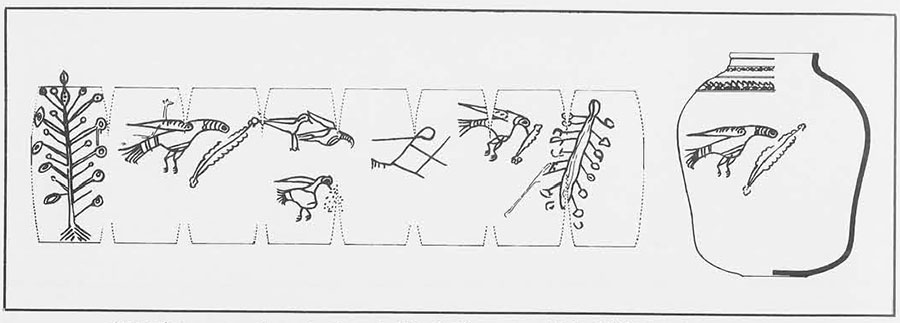

The visible walls of the large monastery at Arminna West were traced and several rooms excavated. One featured a divider wall with crosses outlined in pebbles above and on either side of the arch. Another had a central column of baked bricks, there being alternate layers of eight pie shaped pieces and four semicircles with a cement filling. The bricks were marked in whitewash, each layer with the same letter of the Greek alphabet, a procedure which seems over-meticulous and quite unnecessary. The most interesting single object from the monastery is a large storage jar with birds and a hunter (?) painted on the sides.

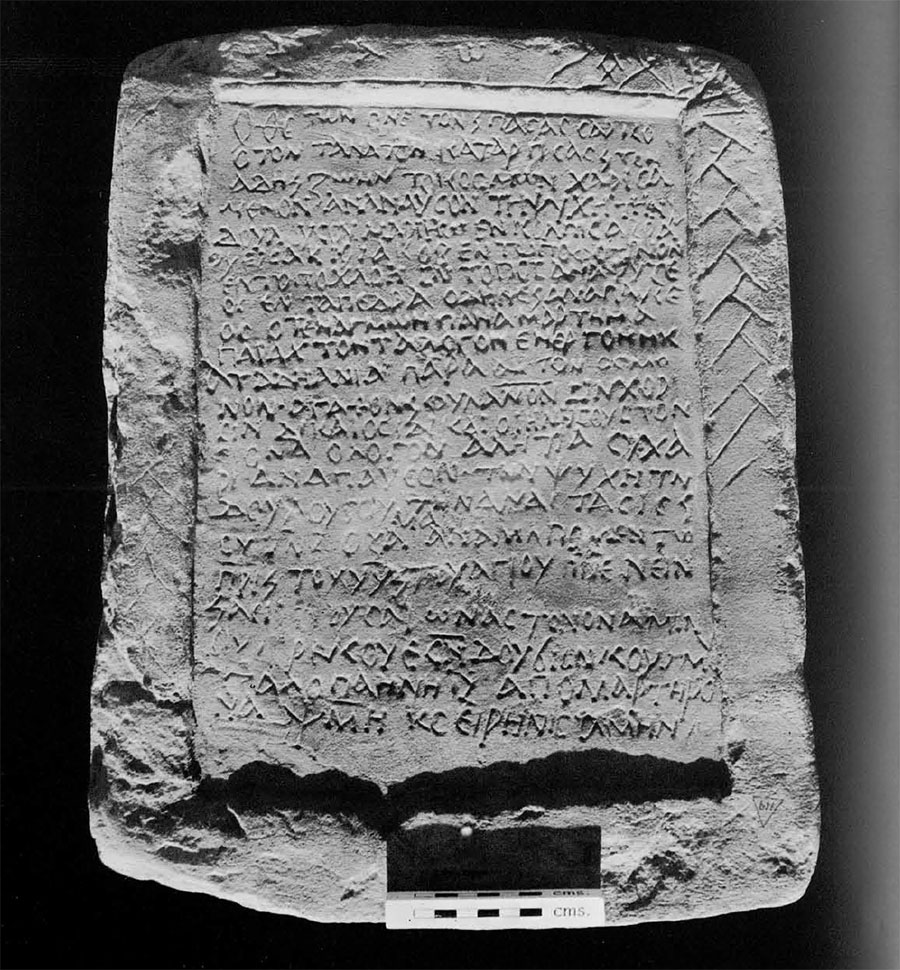

Just to the north of the large monastic complex lay an area of house structures first examined in 1961 and then studies stratigraphically in 1962. The area was inhabited successively in the Meroitic, X-Group, and Christian periods. The most unexpected feature was a Coptic church similar to several of the small churches at Tamit in the south. It had a brick altar surrounded by four piers and originally shielded by wooden altar screens, of which the grooves were found in the paving. Re-used in building one of the piers were fragments of a Coptic tomb stela, so that the church must have been built considerably after the introduction of Christianity to Nubia. In the small space apse a Coptic tomb stela of terracotta showed that the church was probably in use in the tenth century. In a rough translation its text runs thus: “As in the Biblical saying in which the Creator said, ‘Adam, thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return,’ so the blessed Maria went to rest, who was the daughter of Ptou and the daughter of Maria (?), on the 21st of the month of Hathor (in the year of the martyrs) 637. Her years were 39. The good God gave her rest in the bosom of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, beneath the tree of life which is in the midst of paradise…with all His saints, who cried out to God, ‘Amen, so be it, Amen.'” A heavy sandstone Greek tombstone found on the bench-like surrounding wall bears the date of year 748 in the era of the martyrs. The two dates correspond to A.D. 921 and 1032, the Greek text consequently being slightly over a century later than the Coptic.

In a rectangular room added to the church on the north a few tantalizing fragments of fresco were found with traces of the representations of saints and Greek labels identifying them. On one of these walls an early Arabic text was crudely scratched at the time of the advent of Islam. The jar sealing of the archaic period from Toshka West and this graffito in Arabic demarcate a span of some four thousand years in Nubia, to the history of which our excavations have contributed details of interest and significance. Of the material finds of the second season, the United Arab Republic exercised its right to reserve twelve objects for its national collections, and the remainder was assigned to the expedition for subsequent division between the University Museum and the Peabody Museum at Yale.