- Exhibition of Phrygian Art

- Exhibition

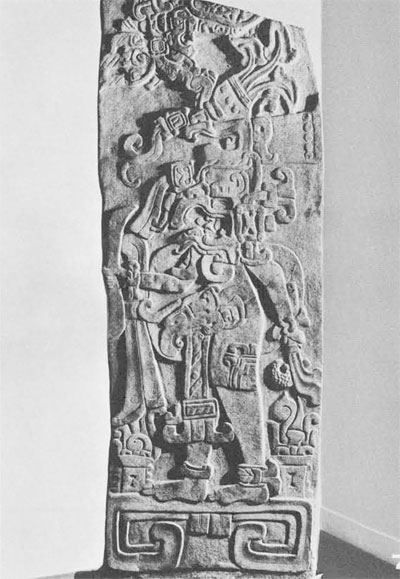

- Erection of the Stela after it has been carefully cleaned

- Exhibition

“…During the past summer a large and beautifully lighted room was granted us. Necessary cases were built, and in September the collections were moved…It was thought…that a proper display of all the objects could be made and the museum thrown open to public inspection…”

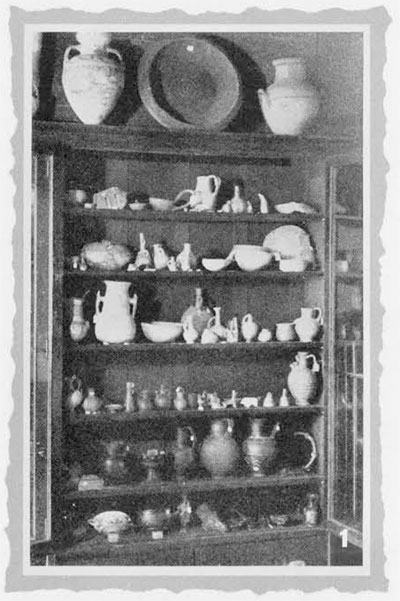

So reads the annual report of the curator of the present University Museum seventy years ago in 1890. An old photograph shows one of these cases in the University Library where the Museum began (1). Such were the problems then, still problems today: galleries, cases, display, the public.

The Free Museum of Science and Art, the name inscribed over the door of the first section of the Museum’s building, grew out of the desire to “throw open to public inspection the treasures within.” The men who made this institution and who formed its philosophy were a dedicated group of Philadelphians, themselves part of the great generation of tastemakers. Our first curator goes on in the 1890 report to lament that the growth of the collections had “exceeded all expectations to the degree that the instructive display of the treasures of the museum is most seriously hampered for want of room.” The present building was begun two years later. Yet seventy years have not changed problems very much. Our collections grow, our ideas change, our treasures need refurbishing. The museum of the founding tastemakers is well reflected in a view of the upstairs main hall of the museum about 1910. A plethora of pieces are all shown together for the viewer alone to select among, in the older Encyclopedic style that was conversant (2). How much taste changes! How different approaches can be! A recent exhibition of Phrygian Art, the loan exhibition from the Turkish Government installed in the same gallery, provides an interesting comparison (3).

Today the responsibility of being a tastemaker is still part of throwing open museum doors to the public. New ideas, new treasures and old ones in new “necessary cases” are differently presented, working toward a better solution. In the permanent, and especially in the temporary exhibitions, the experimental techniques emerge along with the myriad problems to be surmounted. Often an army of specialists must be enlisted just to bring one piece to public view.

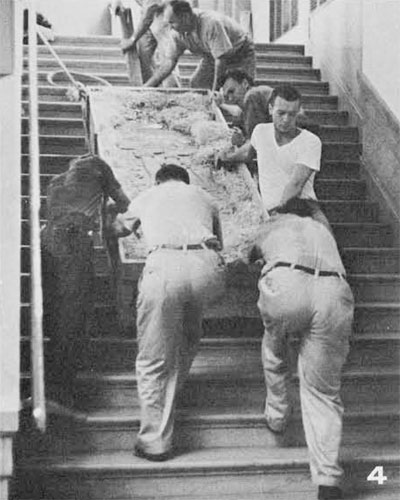

Consider first the outside-of-the-museum agents who make possible “the proper display of objects”– transit carriers, customs officers and brokers, to mention only a few. Eighteen hundred pounds, for example, is difficult to move. The recently displayed Maya stela, part of the generous loan of the Government of Guatemala, is a point of departure. Eight men equipped with ropes, Johnson bars, and know-how transported the piece across the building from the unloading platform towards its installation in a gallery. The stone was gently lowered down the staircase of the main hall roped in its crate and carefully guided (4). A scaffold erected in the gallery to receive the stone made it possible to lift the slab from its box with the aid of a pulley and chains and suspend it in an upright position (5). Roped and tied, the piece had to be measured for a support and base. This step involved still another group of outside-of-the-museum specialists– the iron workers brought in to cope with the balance and anchoring of the stone (6). A visually effective base completes the erection of the stela after it has been carefully cleaned.

However, the piece is still not ready for public inspection.

Light is the one agent that makes the greatest contribution. Light brings the heretofore static work alive, transforms it into the work of art. Color, intensity, and angle of the light bring out the subtle patterns, the complication of the figures in relief on the surface of the stone (7).

More specialists take over. The photographer goes to work with his fine-toothed camera. The curator writes a label that brings the piece alive in another way giving it its fourth dimension. Printed, it is placed beside the stela in the gallery that has been arranged with the secondary things– the foils for the works of art. Wall color is an important aspect, as is placement in terms of the vista and the relation of the piece to the context of the exhibition. Only now can the piece be thrown open to public inspection (8).

The Museum is seventy years older. It is safe to say it is seventy times bigger. Seventy years ago one curator coped with all. Today a small army brings the past to life as part of the work of the modern museum. Museums are living libraries of human history. To bring the art works alive is one attempt to fulfill the desires of the founding tastemakers and first curator to create a comprehensive museum dedicated to science and art.