I came to the United States in February 1998 as a visiting scholar to do research on teaching English to minority students in China. This was my first time here and almost everything was new to me. Before coming to the US, I had read books about American culture; however, it did not come alive in my imagination. So once here I was eager to learn; I would see, read, and experience as much as I could. But nothing did as much to immerse me in the new culture as becoming an International Classroom speaker, giving presentations on China to several thousand American school students.

Choosing the Challenged

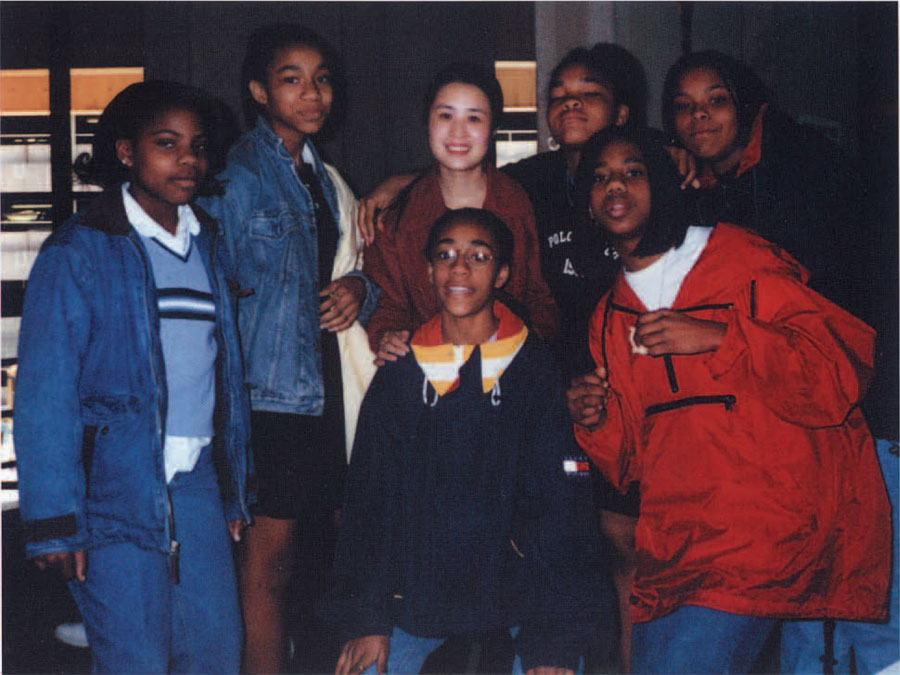

I learned about the International Classroom Program run by the University of Pennsylvania Museum not long after I arrived. The program arranges for international students and scholars to give presentations and workshops about their country and culture to school students and adult groups. I was interested and, driven by the motivation to make the most of my stay here, I decided to take a risk and become a speaker. It was only two months after I arrived that I gave my first presentation (Fig. I).

It was challenging: teaching English in China is quite different from teaching Chinese culture in the US. For one thing. the English spoken here the tone, the accent, and the rules of speaking is a bit different from the English I taught. Also, being a teacher for 15 years didn’t automatically make me an effective speaker, although my positive attitude did help me adapt easily to new situations. With little knowledge of American students and culture, I had no idea what to expect. I tried to anticipate the questions the students might ask and the topics they would be interested in. I wondered what I would do if there were misunderstandings caused by the different cultures, values, and customs, or if I could not catch the slang language. I was curious about what the students would think of Chinese people.

But I also knew clearly that all the answers were there. waiting to be found during my presentations: in the International Classroom there was a world for me to explore and learn and to share.

Prepare for the Worst but Hope for the Best

I entered one classroom after another, in schools in the New Jersey and Philadelphia area as well as at the Museum itself. My presentations went from not bad at the beginning to unexpectedly successful later on. Nothing goes smoothly: it takes time and hard work to unfold a beautiful and meaningful picture. At the outset. I was shocked and even upset by some of the students’ questions and their impressions of Chinese people. Some believed that all women in China had bound feet, so they wanted to have a look at my feet. They recounted a horrible story, which they heard somewhere, that in China baby girls were beheaded after they were born. And they thought the Chinese were cruel and stonehearted for eating dogs. To some, China was something like a demon world inhabited by uncivilized people. A few students came to the classroom with a negative attitude and a few mimicked my foreign accent as soon as I began. Fortunately, it did not take me too many minutes to gain their attention.

With so many eyes focusing on me, so many hands shooting up as we worked out the mathematical operations of the abacus, and so many students practicing Chinese martial arts and Tai Chi—and following me in Chinese traditional eye exercises—I saw that the students enjoyed my presentations and discussions as much as I did. In the end, they asked me back to their schools.

Communication is the Key

International Classroom helps develop cultural awareness: students learn to appreciate and tolerate other cultures and accept people different from themselves. In order to help American students learn more about China and understand Chinese people better, I choose my topics carefully, taking into consideration the ages of the groups, their backgrounds, their interests, and their knowledge about China. Topics cover language, education, daily life, history, and also Chinese arts, science, and religion. With so many misconceptions existing, it is important to give the students the facts. They believe what they see. Therefore, I use many material objects and artifacts such as pictures, postcards, family photos, handicrafts, and traditional dress (Fig. 2). All these things help them get the general picture of what my country and its people look like. It is necessary to point out that no matter how different people from other countries may be, there is still much that is universal, such as music. When I play a piece of Chinese traditional music, “Flights of Fancy—Eight Variations on the Butterfly Lovers,” they immediately recognize the emotions the music conveys. Even hearing it for the first time they can tell that Er Hu, a traditional Chinese musical instrument, produces a sad and melancholy tone that is like somebody crying. Once, my Chinese folk dance stimulated a few students to dance hip-hop in the classroom. We all have fun while learning about each other’s cultures.

Interaction with the students makes the classroom quite lively. I try to involve them in activities and have them participate in the class in many ways. It fascinates the students to learn the Chinese language—a language that is so different from their own. Everyone tries to say loudly the four intonations of each Chinese sound. They are quick at identifying the radicals (elements) in the pictographic characters, such as the female sign in the word for “mom,” the too many mouths in “curse,” the three drops of water in “lake” and “river.” Soon after being taught the rules of the abacus, they are able to add sums on it by themselves. Many are proud of becoming expert in holding chopsticks; they cannot wait to show off their skill the next time they visit a Chinese restaurant. Eye exercises, based on acupuncture points, are very popular in China. They help relax the eyes especially when one is reading and focusing for a long time. They are useful and easy to follow and the students do them in real earnest. It is said that “eye exercises once a day, your glasses away.” Their favorite parts of my presentation are when I demonstrate Chinese martial arts and Tai Chi, and when they dance with the lion mask on their head (Fig. 3). My husband, a Chinese artist, sometimes joins me later in the program, demonstrating brush and ink paintings on paper and teaching the students how to draw Peking Opera faces.

I always leave enough time in my presentation for questions. I am glad to know the students are making connections with what they are learning about my country in their social studies classes. Through their questions they get to know more and change some negative thinking about the Chinese. They don’t even realize they are learning. When I have finished, crowds of students surround me, waiting to tell me their thoughts and asking eagerly for the Chinese characters for their names and the meanings of their names. They aren’t satisfied until they get them. I feel happy and rewarded when I hear them say “Ni Hao” (“Hello” in Chinese) and “Cie Cie” (“Thank you”) to me again and again. I feel we are close in heart, and they remind me of my 8-year-old son in China.

World of Thrills

International Classroom has opened windows that allow me to see this country and its people more clearly, while it has offered me the chance to open more windows on China for the students here and bring my culture to life. I believe where there is more communication, there is more understanding.

While giving, I am receiving. I meet many wonderful people-students, teachers, and the specialists of the International Classroom who arrange everything for me and take care of me all the time. I get opportunities to visit many schools and am invited back for special events like Art Night, International Affairs, and the summer camp workshops. I will have many stories to tell my students when I go back to China. I receive so much love from the students. I get the biggest rewards in the beautiful letters of thanks from the principals and the students. This is what the students write:

“I think all the different cultures from China are incredible… On the bus, we talked about how interesting your interview was.” (Matt)

“It was very neat to learn all about your culture and compare it to our culture.” (Elizabeth)

“You should be proud of your ancestors.” (Stacy)

“The eye exercises were very relaxing. I taught them to my mom.” (Dora)

“You had my attention the whole time. You told me more than I ever thought I’d know.” (Brad)

Almost everyone put at the end of their letter, “I hope you come back and teach us more.”

I am glad I survived in the program as a speaker. More than that, as time goes by, International Classroom becomes part of my life. The experience is something I enjoy and will treasure always. Come and join us in the International Classroom, and you’ll find a world of thrills. Look, the sunlight is pouring in the classroom through the open windows. Immersed in the sunshine, I feel like I am shining.