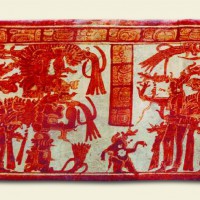

- Mythical dwarf and hunchback dancing the Young Corn God (Photograph K517 © Justin Kerr).

- Human dwarf and hunchback attending a lord (Photograph K1453 © Justin Kerr).

In his book, The Maya’s Own Words, Thomas Ballantine Irving translates a passage in the Popol Vuh, the creation myth of the K’iche’ Maya, regarding a creation of beings prior to humans identified as dwarfs. Creation narratives told in Yucatan also tell of a world, before the present, when the gods fashioned a race of dwarfs from mud so that these creatures would worship them. The dwarfs possessed eyes that could see to the ends of space and time. Before the gods could even fashion wives for them, the dwarfs began to ignore their creators. Rather than worshipping the gods they spent their time creating beautiful pottery, writing books of prophecy, and constructing magnificent buildings of stone. The dwarfs angered the gods so much that they sent a flood to destroy the world. They also destroyed the false sun that gave the dwarfs’ world a dim light. Being possessed of keen intellect and foresight, some of the dwarfs managed to escape the water by stepping onto ledges in caves in the Puuc Hills where the hunchbacks live.

While the dwarfs were hiding in the caves, the gods fashioned a new sun and new intelligent beings to live on the surface of the earth and worship them. The gods made these human beings from corn, placing smoke in their eyes so that they would not be as clever and farsighted as the dwarfs, and when the waters subsided, the earth became a place of corn farmers.

When the surviving dwarfs left the caves to venture out into the world again, the new sun immediately burned them, turning them into hardened clay. Today, many Yucatec Maya believe that the small clay figurines found in the ancient ruins are these refugee dwarfs from the previous creation.

Linguistic Usage Hints of a Lost World

In Yucatec Maya, the words for dwarf connect the Maya creation myth and the Precolumbian images of dwarfs to modern narratives and rituals that focus on a non-human dwarf called the alux (pl aluxo’b). The following list contains some of the vocabulary associated with dwarfs today:

k’at dwarf, potter’s clay

k’at pocot earthen jar

àak turtle, dwarf

kis wild pig’s navel, dwarf

hkis luum earth farter

alux mythical dwarf, earth spirit

uch’bil deformed, twisted

zayan uinico’b hunchbacks that were turned to stone

The term k’at means both “potter’s clay” and “dwarf.” Stephen Houston identified the Cholan equivalent, ch’at, in Maya inscriptions with dwarf images from the Classic period. In their classic ethnography, Chan Kom: A Maya Village, Robert Redfield and Alfonso Villa Rojas write that a local Yucatec farmer, when accidentally uncovering an alux in his hiding place, claimed that the creature was “the color of clay.” Both past and present usages refer back to the creation myth in which dwarfs are associated with clay and the invention of pottery. In the legend of the dwarf king of Uxmal, a folktale told throughout Yucatan and recorded in Andres Bolio’s Land of the Pheasant and the Deer, the dwarf became king by defeating the human king in several contests. One of the contests required that the dwarf create an image of himself that could burn in the fire and still survive. He produced a ceramic figurine. This folktale is used to explain the clay figurines found on Jaina Island, said to have been made by the people of the Puuc Hills on the instruction of their dwarf king. More figurines of dwarfs have been found than representations of dwarfs on either stelae or pottery.

The second gloss, áak is used for both “dwarf ” and “turtle.” In Precolumbian iconography the earth is often represented as the carapace of a turtle. Turtles are sacred to the Yucatec Maya because they are believed to sense the arrival of rain. The east winds that bring the rains are thought to be blown by aluxo’b.

Kis is the gloss for both the “navel of a wild pig” and “flatulence” or “dirty wind.” The compound h–kisluum, “earth farter,” is a metaphor for dwarf. According to the Encyclopedia of Animal Life, the collared peccary of Central America has a digestive tract similar to that of a ruminant, but instead of having four stomachs like a cow, the collared peccary has a single stomach divided into regions. This type of stomach gives the collared peccary a larger belly in proportion to its other body parts and distinguishes it from other species of wild pig. Dwarfs are often depicted by the ancient Maya with large bellies and prominent navels.

When speaking of the mythical dwarf today, Yucatec Maya speakers most often use the term alux/aluxo’b. Uchbil, “twisted,” and zayan uinico’b, “hunchback,” are also qualities used to describe the alux. Zayan uinico’b are the twisted men of a previous world that were turned to stone. Aluxo’b are sometimes identified as the sons of the zayan uinico’b or as the same creature. In the story of the dwarf king of Uxmal, the dwarf king was hatched from an egg that was given to a human witch by the zayan uinico’b.

Images from Ceramics and Stone

Dwarfs and hunchbacks appear together on Classic period funerary pots, dancing with elite personages dressed as the Young Corn God and in palace scenes where they attend a lord. Only one burial at Tikal under Structure 5D-33 contains the remains of a human dwarf, suggesting that achondroplastic individuals depicted on palace scenes were not royal personages but rather members of different social classes. The symbolism apparent in some of the depictions of dwarfs in the Classic period, however, suggests that they were mythological creatures, perhaps represented by real dwarfs at court. The palace scene in the above image depicts both human court attendants and mythological dwarfs. A hunchback holds a dwarf who is drinking something. The miniature size of a tiny dwarf holding a mirror for the ruler identifies him as a mythical alux. On ceramic vessels the dwarf’s role in prophecy enhanced by his clear vision is symbolized by his holding a mirror, an opening to the spirit world, into which the ruler gazes. He wears a headdress that also adorns other mythical dwarfs on carved stone in Yaxchilan.

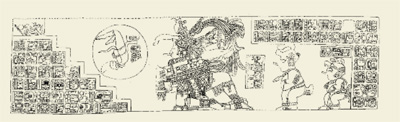

Dwarfs also appear frequently on stelae as attendants of the ruler at sites in the Peten, Usumacinta River Valley, and at Calakmul during the Classic period. They hold torches and feathered fans, often mimicking the dress of the lord they serve. On a stair riser in front of Structure 33 at Yaxchilan, two dwarfs look toward the king playing ball; they peer out from inside a cave on whose walls is written a large hieroglyphic text. They don masks with long noses and hats similar to the garb worn by several Jaina figures depicting buried nobles. The lord’s proximity to these tiny male beings who possesses far- sighted vision, knowledge of writing, and an association to caves and the Under- world, may reflect his power and position. His right to rule is sanctioned by their proximity and the homage they pay to him.

Mythical Dwarfs in the Milpa Today

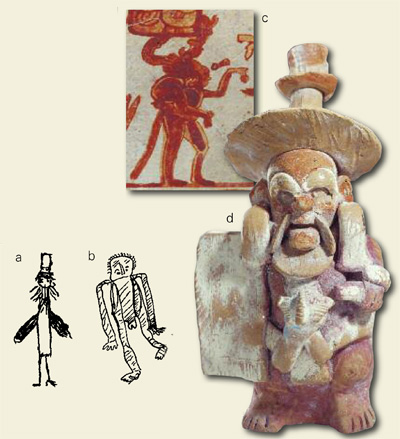

The aluxo’b of today relate to a much transformed and simpler society of men. In modern rural Yucatan, nocturnal aluxo’b are small bearded men who usually wear hats. They have no wives, so they cannot reproduce. In Chan Kom: A Maya Village, Robert Redfield and Alfonso Villa Rojas provide drawings of alux done by villagers (a, b) and several accounts of villagers’ encounters with alux. One of these drawings (a) shows an astonishing resemblance to a clay figurine from the Precolumbian necropolis on Jaina Island (d); the drawing of a hunchback has certain similarities to the hunchback (b) seen earlier in Kerr 517 (c). Between 300 CE and 900 CE thousands of bodies were buried on the island; ceramic figurines from those burials are now exhibited in museums throughout the world and private collectors in Mexico have large numbers of the figurines. The figurines discussed here have all been on public display.

Today the aluxo’b live in a netherworld of darkness, both seen and unseen, neither human nor divine. Despite their reputation for mischief, their nocturnal life and their far sighted- ness make them the ally of local farmers. The impact of the natural and invisible world on survival of the cornfield, or milpa, has insured the continued need for supernatural assistance by the Maya farmer. Small hills near the fields are said to be the homes of the aluxo’b. Food, alcohol, and cigarettes are often left at the hills for the resident alux so that he will continue to protect the milpa. If they require anything from the villagers, the aluxo’b have been known to get their attention by stealing tools, throwing belongings on the floor of houses, and keeping people up all night by screeching or, in one case, playing the guitar badly.

When given food, drink, and ritual homage, the aluxo’b protect the farmer’s crops from hungry animals. In the Maya ruins, they protect the tombs of the ancestors from pillage and looting. The aluxo’b summon strong winds, emit piercing whistling sounds, and propel stones at intruders. The aluxo’b who guard the ruins may also call their dogs to chase looters and archaeologists away if they are at the site at night.

I have been told stories of workers being pummeled with stones and bothered by loud noises in the night if they sleep at an archaeological site. A guard at Dzibanche told me that a dwarf and a pack of wild dogs chased him when he fell asleep on night duty. A neighbor in Quintana Roo showed me ancient small stone houses that she believes were the dwelling places of the aluxo’b. Today the aluxo’b are also said to burrow inside small hills in the bush near ancient ruins.

Although some recent alux sightings are fanciful, many of the aluxo’b in these stories share some commonalities with the dwarfs in the ancient creation story and the Precolumbian images of dwarfs on pottery and stelae. The connection of the aluxo’b with the agricultural cycle and the success of the corn crop today mirror the dance of the dwarf with the Young Corn God on Classic period vessels. Associations with earth, clay, caves, ancient ruins, night, and antiquity beyond our own demonstrate a continuity of belief that has survived, albeit greatly modified, from Precolumbian times. They may be mischievous and prankish, but for today’s Maya farmer, honoring the aluxo’b is one way of safeguarding the milpa. In a greater sense, the rituals and beliefs associated with the alux demonstrate the strength and continuity of tradition and the adaptability of long-held beliefs to a changing world.

For Further Reading

Bolio, Antonio Mediz. The Land of the Pheasant and the Deer: Folksongs of the Maya. Translated by Enid Eder Perkins. Illustrations by Diego Rivera. Mexico: Editorial “Cultura”, 1935.

Corson, Christopher. Anthropomorphic Figurines from Jaina Island, Campeche. Ramona, CA: Ballen Press, 1976.

Irving, Thomas Ballantine. The Maya’s Own Words: An Anthology Comprising Abridgements of the Popol-Vuh, Warrier of Rabinal, and Selections from the Memorial of Solola. Labyrinthos Press, 1986.

Houston, Stephen. “A Name Glyph for Classic Maya Dwarfs,” in The Maya Vase Book, edited by Justin Kerr, pp. 526-31. New York, NY: Kerr Associates, 1992.

Miller, Mary Ellen. Jaina Figurines: A Study of Maya Iconography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975.

Redfield, Robert, and Alfonso Villa Rojas. Chan Kom: A Maya Village. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication #448, 1934.