Photo courtesy of William Fitts

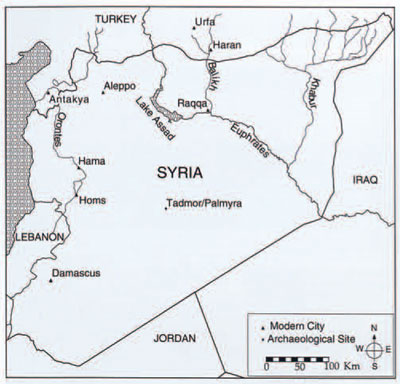

Today, the ancient city of Palmyra, the caravan center and oasis of the Syrian Desert (Fig. I), evokes romantic images of Roman temples and palaces nestled among palms, or Queen Zenobia and her daring revolt against Rome in AD 269-70. Today Tadmor, as the ruins are known, is one of the Syrian Arab Republic’s most popular tourist attractions, a short, and hopefully air-conditioned, trip from Damascus (Fig. 2). But one doesn’t have to venture into the Syrian Desert to catch a glimpse of this “lost city”; soon, Palmyrene sculpture will be exhibited at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. These sculptures (Figs. 3, 4) capture the essence of Roman-period Palmyra, the time of the city’s meteoric rise to power and its cataclysmic demise.

Palmyrene History

By the Roman period, Palmyra’s Efqa Oasis, an isolated pocket of lush green vegetation about halfway between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates River, had been inhabited for millennia (see “Efqa, Palmyra’s Life-giving Spring“). The Roman city’s elites traced their roots to Alexander the Great’s conquest of Syria in 332 BC and the subsequent Seleucid dynasty. As the Seleucid Empire crumbled in the 2nd century BC, the city slipped into the Parthian sphere of influence. The Parthians, an Iranian tribe of horsemen from east of the Caspian Sea, maintained a “hands off” political policy towards their western border along the Euphrates. They tolerated a high degree of indigenous political autonomy to sustain an economically permeable frontier zone. Like other frontier kingdoms bordering the eastern Roman Empire, Palmyra’s allegiances likely shifted with the political winds blowing from east to west and back again. All the while, the accumulation of wealth and power back in the oasis itself steadily led to more active use of indigenous political authority and military force.

An Oasis in the Wilderness

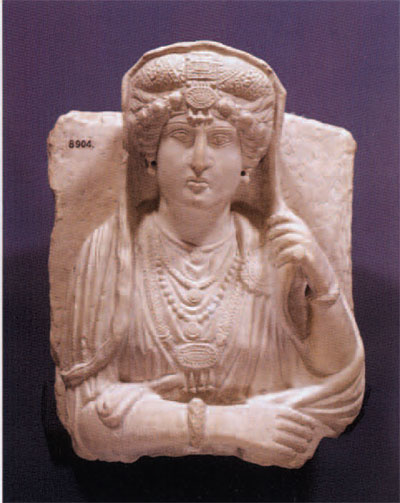

Museum Object Number: 8904

In the late 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, the city became one of the premier economic and political powers of the Roman east, rivaling even Antioch (modern Antakya). Shifts in the trade routes linking China and Rome diverted caravan traffic laden with eastern exotics to Palmyra’s gates. The protection, taxation, and service of these caravans brought great wealth and influence to Palmyra’s citizenry (see “Trade and Taxes”). Though economically prosperous, politically these were troubled times for the area of modern Syria. Hostilities between a weakened Rome to the west and Sassanian Persia to the east brought devastation to most of Palmyra’s neighbors in the 3rd century. The city’s geopolitical situation came to mirror her status as an oasis amid the wilderness. Adding to the confusion, the Roman Empire was rife with separatist movements in the provinces and self-proclaimed emperors. This was especially the case in the east, where Roman rule met the Sassian Empire. In AD 259, the Sassanian king Shapur dealt the Roman legions under Emperor Valerian a crushing defeat near Carrhae (modern Harran). Valerian was captured and dragged off to the Sassanian capital Ctesiphon (modern Salman Pak, southeast of Baghdad), never to be heard from again. At this time, Palmyra’s ruler, Odenathus, met the Sassanian threat head on, and through a series of brilliant military engagements drove the Sassanian forces back to the borders of Persia. He earned the thanks and respect of the Roman Emperor Gallienus, who made Odenathus the most powerful ruler in the east. True to the turbulent times, the good fortune of Odenathus was short-lived. He and his son and heir Herodes were murdered while on a visit to Emesa (modern Homes). Odenathus’s second wife, Zenobia, seized the reins of power, installing her son Vaballathus as ruler over Odenathus’ elder second son by the mother of Herodes. Vaballathus was a minor, so Zenobia filled the role of regent. In short order, she led a coalition of eastern forces in a rebellion against Roman rule. Through a series of military successes, Palmyra seized a large part of the eastern empire, including Antioch, Ankara, Bosra, and Egypt, Rome’s major grain supplier.

Zenobias Rebellion

Museum Object Number: 8902

For a short period, Zenobia’s rebellion posed a major threat to Rome, and it must have seemed the dawning of a new eastern empire, foreshadowing the eventual formal division of the empire. However, Palmyrene independence was an affront to the authority of the new emperor, the former cavalry commander Aurelian. Aurelian efficiently subdued the east in AD 272, expedited by the betrayal of many of Palmyra’s Armenian and Arab allies to the Roman cause. Palmyra was besieged and eventually captured. Zenobia attempted to flee east to Iran, but was quickly apprehended. The various ancient sources disagree concerning Zenobia’s fate. One account relates that after the humiliation of being paraded through the streets of Antioch and Rome by her captors, she spent her remaining days a political prisoner in a villa in Tivoli. Other sources indicate she committed suicide or was put to death shortly after her capture. The imprudent Palmyrenes rebelled again in 273, and this time suffered not only military defeat but also the legendary wrath of Aurelian, who turned the city over to his underpaid troops. Palmyra was pillaged and its fortifications reduced. Palmyra, the “bride of the desert,” was never again an important urban center and gradually fell into ruins. To scholars of late antiquity, Zenobia is an elusive character, blurred by legend and typically vilified by Classical and Arab (male) chroniclers who seethe at female ambition and the notion of an empress. Despite the ridicule, Zenobia’s short-lived ascendance to power captured the imagination of later historians, poets, and dramatists. By no means was a female ruler a new concept. Before Zenobia there had been the Assyrian Semiramis and Egyptian Cleopatra. Zenobia traced her own lineage back to the Queen of the Nile and envisioned her rule as a continuation of the Hellenistic tradition. However, this likely amounted to no more than a fictitious political contrivance. Palmyra has played a pivotal role in the advent, development, and popularization of Near Eastern archaeology. Numerous travelers, adventurers, and scientific expeditions have probed the desert ruins, leaving an enormous literature. These works span the entire methodological and intellectual history of archaeology, from speculative antiquarianism to modern scientific investigations. Today, Zenobia’s legend and her city are a vibrant part of Syria’s cultural heritage and are as alive as ever.

Palmyra: East Meets West

Palmyrene objects grace many of the world’s major museum collections. Much of this popularity is due to Palmyra’s hybrid character. Alexander the Great’s conquest of Syria and the eastern Mediterranean world ushered in one of the world’s earliest episodes of globalization, called the Hellenistic period. Hellenism was the devotion to, or imitation of, ancient Greek thought, customs, or styles, especially by non-Greeks. Hellenistic Syria, more properly termed Seleucid after the local ruling dynasty, was in turn gradually absorbed into the Roman Empire, continuing the Mediterranean influences. As an entrepôt, Palmyra found itself wedged between the Classical world of Seleucid and Roman Syria and the west’s eastern competitors, consecutively the Parthian and Sassanian empires. Because of this, Palmyrene culture incorporated elements of west and east, a Classical Mediterranean veneer over a Semitic Near Eastern base. The polyglot of Palmyrene personal names recorded in inscriptions reveal a multiethnic population of Aramaeans, Arabs, Greeks, and Persians. The predominant languages were Greek and Palmyrene, a dialect of Aramaic. Palmyrenes practiced a diverse array of religions, typical of the religious ferment of late antiquity—pagan cults, as well as Zoroastrian, Jewish, and early Christian communities could be found in the city. Arguably the most important Palmyrene cult was that dedicated to the Semitic god Bel (Fig. 5).

“Houses of Eternity”

Photo taken by the Wolfe Expedition, 1885.

For Palmyra, unlike other ancient Syrian cities, we possess a wealth of information on the lives of the elite thanks to their elabo rated burial customs. Well-to-do families built large subterranean tombs, called hypogeum, or aboveground stone sepulchres in the form of houses or towers (Figs. 6-8). Palmyrenes called their tombs “houses of eternity” and took great pride in their construction and long-term maintenance. Many of the tombs contain historical inscriptions, and the interiors were richly decorated with wall paintings and funerary sculptures representing deceased individuals and family groups. Some tombs contained ornately sculpted sarcophagi, but most people could not afford such luxury. Their mummified remains were laid on shelves within rectangular niches in the tomb walls. A limestone slab called a loculus, typically bearing a sculpted portrait of the deceased, sealed each compartment. The Museum’s two sculptures belong to this category. These portraits were closely linked to conceptions of the afterlife. The word for funerary stele in Palmyrene, nefesh, also meant “soul” and “person, self.” The sculptures often depict the deceased at moments of great earthly happiness, dressed in finery, surrounded by family, friends, and servants, often leisurely reclining on couches at banquets.

Photo taken by the Wolfe Expedition, 1885.

The wealthy lady depicted in our first sculpture is decked out in her finest jewelry, turban, and veil,(see Fig. 3). Her clothes, style of jewelry, and her pose—with the left hand slightly pulling back the veil—indicate she died sometime during the 3rd century AD, when Palmyra was at the height of its glory. Nineteenth—century antiquities dealers carved the spurious Palmyrene inscription in an attempt to raise the sculpture’s sale price.

The second funerary relief of “Malkû, son of Moqimu. Alas! ,” as recorded in the Palmyrene inscription, reveals how one elite man intended to spend eternity. Malkû reclines on a cushion, wine bowl in hand and belt loosened (see Fig. 4.). Two youths, interpreted as servants (Ingholt 1935), stand behind him. One holds a cup and dipper, the other an amphora. Malku’s manner of dress and dagger are of the Persian style. Slits down the side of the men’s tunics facilitate riding. Malkû also wears a chlarnys (a riding cloak) fastened by a clasp on the right shoulder and wrapped around his left arm. Malkû’s Persian costume was “the usual state-attire of the well-to-do Palmyrene” (Ingholt 1935:71) and dates the sculptural work to between AD 150 and 272. Behind Malku is a dorsaliurn, a drapery or veil suspended from two rosettes from which rise two small palm leaves. The dorsaliurm distinguishes the deceased from other individuals in the scene and represents a Hellenistic influence. In Hellenistic art, the dorsaliurn was employed to denote a house interior. Here the connotation is that Malku now resides in his “house of eternity.”

Penn and Palmyra: Problems of Provenance

Photo taken by the Wolfe Expedition, 1885.

Palmyrene sculpture formed part of the University of Pennsylvania’s earliest recorded display of antiquities. exhibited in College Hall around i888 (Thorpe 1904). Archival research conducted by the Museum’s Senior Archivist, Alex Pezzati, indicates that Palmyrene statues, tesserae (terracotta tokens), and lamps were deposited at Penn by the prominent Philadelphia collector, and later member of the Museum’s Board of Managers, Charles Howard Colket (1859-1925, Penn A.B. 1879, A.M. 1882). The Museum subsequently expanded its Palmyra collection through purchases made by the Babylonian Exploration Fund in 1889 during its second expedition to Nippur. The expedition was led by John Punnett Peters and part of his assignment was to acquire objects suitable for the newly founded Museum to be housed in the University Library, now the Fisher Fine Arts Library. This he did at nearly every stop on the way from Constantinople to Baghdad. Peters chose to make the arduous journey from Damascus to Baghdad via the perilous desert caravan route east to the Euphrates near Deir ez-Zor. His decision was influenced by the prospect of seeing Palmyra and making researches in the ruins and surrounding vicinity. He departed with a camel caravan on November 18, 1889.

Peters is uncharacteristically silent in his various writings as to how he obtained Palmyrene objects. His published account of the expedition leads one to suspect ulterior motives lay behind this secrecy: “The Turks strictly forbid the removal of antiquities; but illicit digging continues, and almost every traveller buys and removes a few busts and mortuary inscriptions” (Peters 1904:31). “The natives brought to my camp, or offered to bring, many antiquities of the common Palmyrene type” (Peters 1904:32).

Peters never states he made purchases, and his accounts show no expenditures for antiquities while at Palmyra. In an entry for January 26, 1905, Hermann Hilprecht, the Near East Section’s first curator and epigrapher for the Nippur expedition, notes in the section’s first registry of objects that the Palmyrene objects were “Taken from the ruins of Palmyra by Dr. Peters in connection with his visit.” There are no entries for the Colket Collection, and I suspect Hilprecht appended it to the Peters Collection. Thus, the pieces discussed herein could belong to either collection. Like many of the Near East Section’s objects, the sculptures have rarely left storage. Two of them were loaned for a brief period to Yale for an exhibition in 1954 (Ingholt 1954). Father Leon Legrain published the tomb sculptures in an article in The Museum Journal dated 1927 and the tesserae in The Culture of the Babylonians (1925). A group of four lamps remains unpublished.

It is no surprise that Penn would acquire artifacts from Palmyra. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, Palmyrene curios were in vogue. Consequently, small collections of “Palmyrainica” are scattered throughout Europe and North America. The explorers Robert Wood and James Dawkins first sparked public interest in the city following their visit to the ruins in 1751 and the publication of their lavishly illustrated folio volume The Ruins of Palmyra in 1753. The ostentatious Palmyrene architectural and sculptural styles created an immediate sensation, originating an architectural movement in Europe and a demand for Palmyrene antiquities. So, too, the scraps of Palmyra’s history as recorded in Classical and Arab sources, albeit tainted by the political biases of her chroniclers, provided abundant grist for the West’s orientalist mill. Queen Zenobia and her ill-fated rebellion were the subject of numerous plays, and the queen crops up in the prose of Lord Tennyson and Nicholas Michell, the photography of Julia Margaret Cameron, and paintings by Giambattista Tiepolo and Herbert Gustave Schmalz (Stoneman 1994). However, the story of Palmyra really ends with Zenobia. Thanks to modern archaeological and historical investigations we are beginning to understand Palmyra’s rise to fame.

Efqa, Palmyra’s Life-giving Spring

The main oasis at Palmyra is fed by a subterranean spring known as Efqa. Aramaic for “source” or “issue of (water). The spring emanates from a grotto that extends 600 meters (approximately 1800 feet) to the base of a nearby hill. the Jebel Muntar southwest of the city. The spring maintains a constant rate of flow, providing 5,000 cubic meters of water per day (over 1.32 million gallons. or enough water to fill five medium-size houses). In antiquity, as well as today, the water flowed into eight wells and was used to irrigate gardens and groves of olive trees and date palms. The abundance of palms gave rise to the Roman name for the settlement. Efqa is also renowned for its healing properties. The water is sulphurous, mildly radioactive, and remains at a constant 33″C. The ancient Palmyrene attached great religious significance to their oasis: the entrance to the spring was the site of a small religious sanctuary and altars have been found in the vicinity dedicated “to him whose name is blessed eternally, the good and the merciful.” Water use was highly regulated. A city official, called a curator, oversaw water distribution and the maintenance of the waterworks.

Palmyrene Sculpture to See Light of Day

In October of 2002, three new ancient Mediterranean world galleries will open at the University of Pennsylvania Museum: “An Introduction to the Classical World”: “The Etruscan World”: and “The Roman World.” The project will complete the reinstallation of the suite of Classical galleries initiated in 1994 with the opening of the permanent exhibition “The Ancient Greek World.” Approximately 1000 objects in these three new galleries will represent a cross-section of the material culture of the Etruscan and Roman peoples, ranging in date from the 9th century BC to the 5th century AD. The two Palmyrene funerary reliefs, recently cleaned by conservator Tamsen Fuller. are now ready for-installation in the new Roman World Gallery (Donald White, Senior Curator; Irene Bald Romano, co-curator and coordinator; Ann Blair Brownlee. co-curator). More information is available at http://www.sas.upenn.edu/sasalum/ newsltr/summer2000/legends.html.

1753. The Ruins of Palmyra. London.Hilprecht, H. V.

1893. “Report of the Curator of the Babylonian Section.” Report of the Board of Managers of the Department of Archaeology and Palaeontology of the University of Pennsylvania (1889-1892), pp. 11-14. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.Ingholt, Harald

1954. Palmyrene and Gandharan Sculpture. New Haven, Ct: Yale University Art Gallery.

1935. “Five Dated Tombs from Palmyra.” Berytus 2: 57-120.

Legrain, Leon

1925. The Culture of the Babylonian, from Their Seals in the Collections of the Museum. Publications of the Babylonian Section 14. Philadelphia: University Museum.

Peters, John Punnett

1904. Nippur or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates. Volume 2. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Stoneman, Richard

1994. Palmyra and Its Empire. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Thorpe, Francis Newton

1904. William Pepper, MD.,LL.D. (1843-1898) Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company.