To speak of a discipline of Partho-Sassanian archaeology is really to use a misnomer from the very start. There is no broadly preached philosophy or recognized methodology when it comes to the excavation of Partho-Sassanian sites, the interpretation of their objects, and the illumination of their history. This harsh critique is in no way intended as a slight on the very considerable progress that has been made, particularly in the last decade, towards a better understanding of the Parthians and Sassanians. It is almost fashionable to talk of Sassanians these days in contrast to the extremely poor coverage they received only ten years ago. This happy state of affairs does not alter the fact that museums and university departments in general are not capable of handling all that is involved in Parthian and Sassanian studies. At times, the peoples of these two great empires must be studied in the shadow of the Achaemenian or Classical giants, or be considered as the inferior predecessors of the Islamic or Byzantine civilizations. Even when the Parthians and Sassanians have been the subject of research in their own right, there has been a tendency for academic schisms to develop. Linguists dispute with historians, anthropologists with art historians about the best way to clarify the many problems.

The Parthians came to power as Greek strength in the Orient waned. The Sassanians took over when the Parthian kings had become powerless and feeble. The downfall of both the Parthian and Sassanian kings was probably a result of their inability to accommodate the needs of a dynamic and restless society. In their heyday the kings governed an area comparable to that of the empire of the Achaemenians whose heirs they in fact considered themselves to be. But they held sway over this “greater Iranian world” with far less than absolute authority.

The diverse area in question finds its western boundary in the mountains of Armenia and the plains of the Euphrates. The eastern extremity may be considered the Hindu Kush and the Northwest Frontier region of India. To the northeast of the Iranian plateau, Parthian and Sassanian influence reached into the river basins of Central Asia. To the south, the Persian Gulf affords the only extensive maritime frontier of the two empires. Generally speaking, the Sassanians controlled more of this area with greater might than did the Parthians. Despite that difference, the two empires are basically very similar and can be examined by the same general methodological approach. To study either empire within the artificial boundaries of the modern countries is absurd. The cultural homeland was the Iranian plateau; the administrative capital was located in what is now Iraq; and some of the most important provincial centers were in what is now Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. (See the map on page 35.)

The breadth and diversity of the empire demand that the student be familiar with many varied cultural, linguistic, and even social conditions. With petty kingdoms emerging to challenge the central authority, their differences were encouraged or at least not obliterated. The various minority groups experienced both prosperity and persecution. Each group may have been capable of inspiring artistic and cultural change which would become part of the mainstream of Partho-Sassanian culture. It is the task of the student to recognize the regional and sectional differences while at the same time identifying trends that were common to the empire as a whole.

What are the means at our disposal for the study of the Parthians and Sassanians? For the purposes of this paper we can consider three broad categories of inquiry, namely field archaeology, the art of the object, and language studies. A very popular practice in Middle Eastern archaeology is the field-survey approach. It is dangerous to apply this technique in the Partho-Sassanian world. It was acceptable in the pioneer work done by Robert Adams on the Mesopotamian plains because the ceramic types, which are the basis of any such study, were reasonably well known. There are differences, however, between the pottery found on the Iranian plateau and that found on the Mesopotamian plains. There is a far greater incidence of glazing, for instance, in the ceramic types from Mesopotamia. Then again, the types on the plateau are not universally consistent. The Partho-Sassanian pottery from the province of Fars cannot be used as a safe guide for the identification of sites in Kurdistan, although both regions lie within the Zagros mountain chain. The only survey within a given region that can be considered really reliable is one that follows the excavation of a site within that general area. In this way the basic ceramic types are known and important factors encountered in a survey are not overlooked simply because of lack of recognition.

The immediate obstacle facing the would-be excavator of an imperial Partho-Sassanian city is the fact that many of them have been built upon up to the present day and have been subjected to constant rummaging for building materials and to denudation by ploughing. In these cases our information is usually limited to the knowledge that there exists a piece of city wall or a ruined fort, for which it is often difficult to determine when it was built and for what purpose. Rayy is an obvious example. Excavations were conducted there by Erich Schmidt between 1934 and 1936. Digging by commercial operators and the vast extent of the site reduced the chances of making many interesting discoveries using conventional archaeological techniques. The trash pit was often the source of interesting finds, but enormously destructive to the archaeological context. In fact, the pit may be the worst obstacle in the excavation of an early mediaeval city.

City sites that lack the late overburden are a better target for the archaeologist. That condition is met in the case of the Sassanian New Town whose foundation was a common phenomenon. Founded to create a new tax base, to maintain control of a trade route, or simply in the aftermath of a natural disaster, these New Towns probably often lacked a natural incentive for growth. The subsequent decline and abandonment of these settlements should provide the perfect situation for the excavator.

Nonetheless, the lateral extension of the ruins presents difficulties that do not occur in the case of the superimposed strata of a protohistoric mound with which archaeologists are more familiar. On a site covering three square kilometers, the problem of what to look for and where to dig becomes much more acute. Ironically, the very thing that saved the city from obliteration—the lack of a mediaeval overburden—is what causes the ruins to waste away. Without later levels to cap the ruins, walls erode with nothing preserved but the foundations. It seems to be a curious phenomenon of Partho-Sassanian mud-brick architecture that foundations were often built in the form of casemented walls packed with fill. The foundations are like a platform whose supporting walls do not bear any direct relationship to those that were above. With unchecked erosion the plan of the building disappears; the objects contained within the platform foundation fill are as unrelated to the structure as they would be in a pit. The most celebrated example of a Sassanian New Town, Jundi Shapur, seems to have suffered from precisely this phenomenon. According to information derived from test trenches sunk by the Oriental Institute in 1963, such mounds as do exist on the site appear to be nothing more than huge piles of fill that perhaps belonged once to some form of casemented platform, as a substructure for buildings long since disappeared.

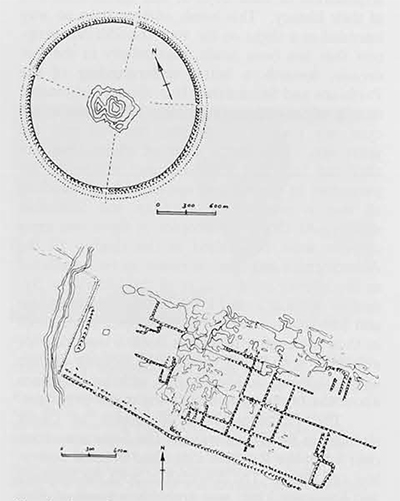

Traditionally the foundation of Jundi Shapur has been taken to mark the introduction of a western city plan into the Iranian world, contrasting with the traditional circular city plan of the Parthians. Ibn al-Balkhi, writing in the twelfth century, described Darabgird city walls as being circumscribed as though with a pair of compasses. By contrast, the rectangular grid pattern of Jundi Shapur, founded in the third century with the aid of Roman prisoners of war captured by Shapur the First, has shown up very clearly on aerial photographs. Yet Donald Hansen and Robert Adams concluded tentatively that “the rectangular plan and interior grid pattern of the city is to be seen more as the ambition of its founder than as a functioning reality. Moreover, since the lines articulating the grid pattern are found to consist not of ancient roadways at surface level but of low raised ridges, their significance as evidence for an overall plan of the city in any case is subject to challenge.”

The poignancy of this shortcoming may be realized when it is pointed out that Jundi Shapur would have been the perfect Sassanian site to excavate. A few historical notices, classic aerial photographs, and the promise of the ruins of a famous medical school suggest the makings of a sound archaeological program. The moral of the story is perhaps that we must excavate sites with intact strata and not necessarily those with just a pretty picture and a good name. We must engage all the benefits of scientific gadgetry, including magnetometric survey and infrared photography. Mechanized earth-moving equipment will probably be essential to any program undertaking the excavation of a large city. To do less will be either inadequate or irresponsible.

Attention need not be confined to the massive urban centers, although they are one of the most fascinating problems of Partho-Sassanian archaeology. Isolated forts and palaces can be expected to disgorge all manner of artifacts and decorative embellishments befitting petty nobles, provincial governors, and garrison commanders. The discovery of any stratified and datable finds is a tremendous contribution to our understanding of Partho-Sassanian art. For too long we have been unable to tell, for instance, whether there was a difference between tastes prevalent in Sassanian as opposed to early Islamic times. The term “Late Sassanian/Early Islamic” appears all too frequently on museum labels which ideally should be more precise.

Reference has been made to the often fragmented nature of the Parthian and Sassanian empires. It has often been theorized that in general the Sassanians were much less tolerant, more nationalistic, and therefore less likely to tolerate the existence of local cults than were the Parthians. It would be of particular interest, therefore, to test this theory by the excavation of a settlement lying in the lee of a Zoroastrian fire temple, the material symbol of the Sassanian state church. As yet we cannot be too certain what the relationship between the state church and the local community really was. The excavations of the German Archaeological Institute at Takht-i Sulaiman give us revealing insights into the makeup of one of the great national shrines. Work done by Roman Ghirshman in Elymais offers us tantalizing glimpses of local cults possibly snuffed out by orthodox Zoroastrian zeal. To complement the picture we should examine one of the fire temples in Fars, together with the adjacent village to try to see what part the temple played in the lives of the people. For instance, there is the plain of Farrashband where Mihr Narses, Bahram’s prime minister of orthodox Zoroastrian faith, founded four fire temples in honor of his sons. Without the focus provided by excavation, the remarkable discoveries of Vanden Berghe of numerous fire temples throughout Iran are left hanging somewhat in mid-air.

We turn now to the second category of inquiry, namely the art of the object. One of the most urgent needs in Partho-Sassanian studies is the improvement of our understanding of metalwork. Sassanian silver has captured the attention of private collectors as well as museums. The market demand and our abysmal ignorance about the art have resulted in the proliferation of forgeries, some skilfully produced, others atrociously done. The low standard of academic knowledge inspired the organization of an exhibition and conference to study the problems of Sassanian silver. The original exhibition was organized at the time of the International Congress of Orientalists in Ann Arbor by Oleg Grabar who also wrote the text for the Catalogue, Sassanian Silver, University of Michigan Museum of Art, 1967. Subsequent conferences were held in 1969 at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and in 1971 at the Fogg Museum of Art.

It can now be claimed that the techniques of the manufacture of Sassanian silver vessels can be determined by various electronic microscopic probes and X-ray photography. Such tests are with increasing precision able to tell us, for instance, whether a vessel was cast or hammered; whether alloyed or gilded; and whether the design was added by a repousse or chasing technique. It is also possible to analyze the metal and determine the actual silver content of the so-called silver vessel. Though a chemical analysis of a plug drilled from the vessel is preferable on account of the greater size of the sample, reducing the possibility of misleading result, a non-destructive method of analysis—termed neutron activation analysis—has been devised, whereby a minute trace of the metal is removed merely by rubbing the silver with a quartz crystal. The pioneer work in this field has been by Aden A. Gordus of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Michigan. Precious objects are not impaired by the analysis. In time it seems likely that sufficient correlations of data will be made so that it will be possible to connect certain vessel types with different silver compositions and therefore to identify them with particular mines and areas of manufacture. It should be stressed strongly that progress beyond the purely analytical stage can be made only in conjunction with art historical studies, which must establish hypothetical groupings on the basis of style in order to determine the existence of regional characteristics. So far, exhaustive stylistic studies have not been completed.

One of the problems with the analysis of silver is, of course, that it is a precious metal, and therefore possibly the object of constant recycling.

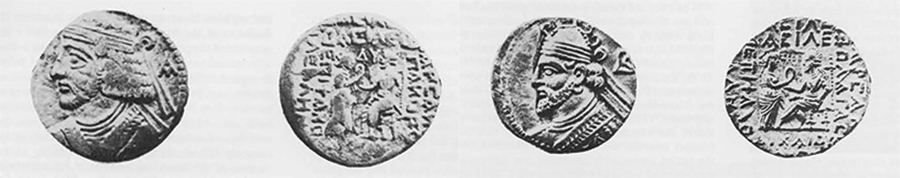

It is impossible to establish dating criteria in the manner of C-14 dating on the basis of chemical analysis alone. One of the aids at our disposal is the numismatic data of the period. Bearing in mind the frequent illegibility of the inscriptions on coins, we are, at any rate, fortunate in having dates on the coins for part of the Parthian period and for most of the Sassanian. Some vessels bear inscriptions too. The relative silver content of the vessels is usually lower than that of the coins. A close correlation between the dated coins and the undated vessels is therefore difficult to obtain. But the differences do tend to be consistent. An abnormally low or high silver content in a bowl automatically indicates that the vessel may have been manufactured outside of the Sassanian empire. The difference can be one of time as well as of area. For instance, a silver bowl with dubious style might be suspected of being a modem forgery made with ancient silver if the silver count demonstrated that the vessel was made with silver derived from melted-down coins. Or it might have been an ancient copy made by someone who had access neither to a good original nor to the correct raw materials. More important than merely establishing the authenticity of given works of art, albeit to the great satisfaction of their owners, the techniques of analysis are a great break-through in Partho-Sassanian studies. They promise penetrating clarification of the problems of a regional and universal art in the Partho-Sassanian world.

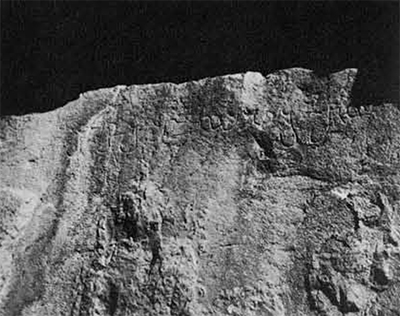

The third category of inquiry is language study which provides us with a history of the Partho-Sassanian period. In the absence of many contemporary historical writings written within the empire, inscriptions on rock reliefs, and seal stones are extremely important for telling us who owned what and at what time. We have mentioned the horrendous nature of Parthian and Sassanian inscriptions. It is a characteristic of the middle Persian texts and inscriptions that they were written in a form of Aramaic lettering which became increasingly more cursive and illegible. This means that the limited source material available is not only hard to translate and interpret, it is often laborious simply to read and transliterate. Trilingual inscriptions help. And invaluable commentaries are to be found in the texts that deal with the histories of the minority groups. Outstanding in this regard are the works of Neusner and Fiey, who handle respectively the histories of the Jewish and Christian minorities under the Parthians and Sassanians.

It is from the royal inscriptions that historians have drawn the outlines of the imperial administration and social organization. Cities belonging to the empire are listed in the great inscription of Shapur at Naqsh-i Rustem. The names of many cities are recorded in the mint marks carried on Sassanian coins. Not everything that is written can be taken at face value. It would be interesting, for example, to know whether coins really were struck at all the cities mentioned on the coins or whether the practice reflects an official desire to represent the Sassanian “king of kings” as being omnipotent. Coins struck in the capital could bear the name of provincial cities to herald the might of the Sassanian Empire. This would be another example of the type of artificial propaganda encountered in the royal rock reliefs. Neither practice was really effective in unifying a potentially revolutionary society.

In the Hajiabad inscription near Persepolis, Shapur speaks of shooting an arrow before an audience of rulers (i.e., petty kings), royal princes, and great and small nobles. We can hypothesize, therefore, that in the third century there existed a particular pecking order amongst the feudal rulers of the Sassanian Empire. However, there is no automatic guarantee that the same meaning can be given to the titles if they were used, for example, in post-Sassanian texts to refer to the years following the social revolutions within the Sassanian Empire of the sixth century. Also, there may be a difference between the names included in an official list of dignitaries and those who actually directed the course of government. Richard Frye in The Heritage of Persia speaks of the “proliferation of titles and honorifics in the course of Sassanian history.” The difficulties of assigning the same meaning to titles for all periods are underlined by the fact that at a time when the Parthian kings were losing their charismatic appeal they seem to have adopted titles and expressions in order to establish their right to rule as heirs of the Achaemenians. One such title was “king of kings.” In some of the titles there may be nuances of meaning that were not present in the original. The history of the period involved is intricate even though many of the facts are obscure. To pass any sound judgment on the nature of Partho-Sassanian social organization it is essential to know the meaning of a title and the time when it was used.

It is obviously not possible to cover all the aspects of Partho-Sassanian studies in this short article. Those topics mentioned are some of the subjects whose study is vital to the advancement of our knowledge. We do not really know, for instance, exactly how the empire was organized. We do not know what comprises a Partho-Sassanian city. Who were its artisans and artists? In a society where the state religion forbade the contamination of the holy elements of fire and water, what was thought of the blacksmith who worked iron to make trappings for the horses that everyone rode? What was thought of the silversmith when silver vessels were more desirable than ceramic ones, but when the process of manufacture was tantamount to a sacrilegious act? Were, then, the ritualistic symbols of the state church no more than empty images? Were the dancing girls whom we see draped in diaphanous veils on the silver vessels more typical of the life than the pious priests forever standing before their incense burners? Was there a double standard: one for royalty and another for the middle class? It will take all the combined efforts of many academic disciplines to answer these and similar questions. It can and should be done.