Archaeological research in Crete has always maintained a tenuous and sometimes contrary bond with evidence of traditional human activity in the Cretan countryside. In early publications of scholars such as Harriet Boyd Hawes (1908:29-34), references to contemporary Cretan practices were used as reinforcement for cultural interpretations of Minoan remains. This unencumbered use of ethnography, frowned upon in the methodologically strict confines of present-day Aegean archaeology in human interaction with the Cretan environment until the second half of this century. While traditional Cretan practices in the use and manipulation of raw materials were frequently recorded by early travelers and archaeologists through casual observation and the recognition of visual similarities with ancient remains, long-term anthropological research on traditional (pre-mechanized) forms of agricultural and pastoral existence in Greece, such as the excellent studies by Koster (1977 and 1981) and Chang (1981), has lent itself more accurately to comparative use in archaeological interpretation and serves as a guideline for thinking about what might have occurred in antiquity within a specific environment.

If examined with the telescopic sight of an archaeologist, the material elements of a shepherd’s existence in the Dictaean Mountains of eastern Crete (Fig. 2) provide striking evidence for traditional man! land interaction and its possible archaeological remains.

The Plain of Limnarkaro

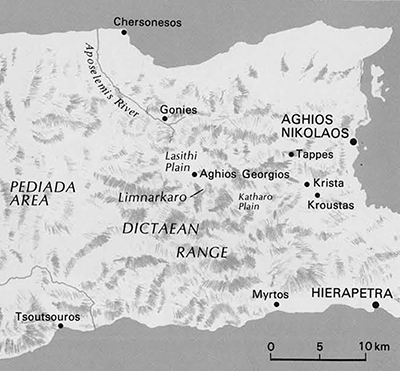

Beneath the limestone crest of Mount Dicte, south of the well-known Plain of Lasithi (elevation 840 m) is the smaller upland plain of Limnarkaro (Fig. 1), fed by the winter wash of Spathe, the highest point (elevation 2148 m) in the Dictaean range. This small basin, at an elevation of 1100 m, was the pastoral domain of circa thirty shepherding families from the village of Aghios Georgios in the Plain of Lasithi until the second quarter of the 20th century.

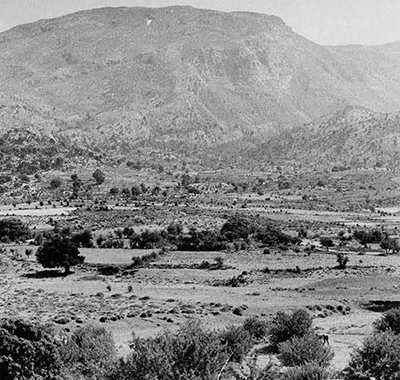

Limnarkaro (Fig. 3), ringed by low foothills spotted with wild pear (Pyrus) and with remnants of the original oak forest (Quercus), also supported at its margins a variety of shrubs, including hawthorn (Crataegus) and butcher’s broom (Ruscus). The western edge of the plain was covered in part with heather (Erica arborea), and the denuded center of Limnarkaro was characterized by rounded thickets of prickly and hirsute shrubs, including thorny burnet (Sarcopoterium spinosum), spurge (Euphorbia acanthothamnus), and several varieties of thyme (Thymus). The main spring of Limnarkaro on the eastern edge of the plain was surrounded by walnut trees (fugtans regia) and clumps of rush (funcaceae).

The Mitato

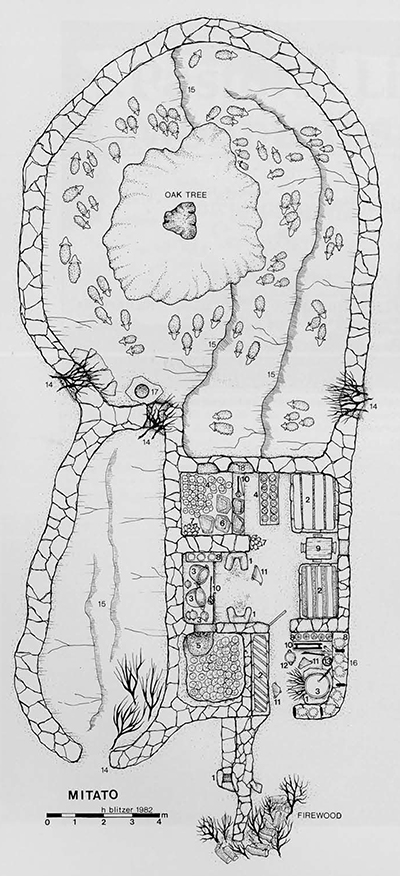

The core of existence of these shepherding families in Limnarkaro was the mitato (Fig. 4), the combined field house, cheesemaking establishment, and corral, that was situated on hillslopes in and around the plain. Constructed of unmortared slabs of local laminar limestone, the mitato had a flat roof composed of wooden beams overlaid by extra-sized limestone slabs onto which various local plant materials and then earth had been packed and stamped. The building frequently consisted of one or two large rooms that had been subdivided into living!working and storage spaces as needed (Fig. 5). The corrals, including a holding pen and a larger area where the sheep remained overnight, were often attached to the mitato dwelling.

Archaeological research in Crete has always maintained a tenuous and sometimes contrary bond with evidence of traditional human activity in the Cretan countryside. In the early publications of scholars such as Harriet Boyd Hawes (1908:29-34), references to contemporary Cretan practices were used as reinforcement for cultural interpretations of Minoan remains. This unencumbered use of ethnography, frowned upon in the methodologically strict confines of present-day Aegean archaeology, nevertheless has foundation in human interaction with the Cretan environment until the second half of this century. While traditional Cretan practices in the use and manipulation.

Several stone-built hearths (parathies or parathies), frequently with clay linings (Fig. 5:1), could be found inside a raised roof, a design that allowed some smoke from the hearths to escape. Indoors, the blinding smoke from cooking fires was simply endured.

The living and working areas of the mitato were visually inseparable, with stone benches and platforms (pezouiia) covered with thyme-filled mattresses (Fig. 5:2) serving as sitting and sleeping areas. The beaten earth floor of the mitato was sometimes fashioned into low shelves on which were stored the heirloom round-bottomed copper cauldrons (tsigies or kazarda) used in cheese production (Fig. 5:3 and Figs. 9, 10, 12). Sheep bells (koudounia) of various tonalities made in Herakleion (copper) or imported from mainland Greece (brass) were hung throughout the building (Fig. 5:7).

Wheels of cheese (kephalotyri) aged initially on wooden shelves or earth platforms (Fig. 5:4) and later in the tyrocheli (Fig. 5:5), a naturally refrigerated storage room that had been dug out of the mountainside and that was accessible from the main living area by means of a crawl space. Baskets (toupia) used as moulds in the production of cheese wheels (Fig. 5:8 and Figs. 10, 12, 13) were imported to Limnarkaro from the basketmakers’ production center at the village of Conies (in the Aposelemis River valley north of Lasithi; Fig. 2) and, via Herakleion, from craftsmen in villages near the north coast town of Rethymnon. These baskets, in three sizes, were made of wild olive prunings (Oteo europea, spp. oieaster, known in central and eastern Crete as argouiida) or of branches of styrax (Styracaceae, known as astirakas), bound together with vroulo, a form of rush that grows well at seeps and standing water. Goatskin sacks (askoi or, less frequently, tsouvaiia; Fig. 5:8 and Fig. 14) were used to store mizithra (a liquid form of cheese) before shipment to market.

Water in the mitato was stored in clay jars (stanmes and kouroupes) made primarily by potters from the central Cretan village of Thrapsano. Other types of clay vessels as well as stamnes were also brought to the Lasithi area by potters from Kentri in lerapetra and more rarely from Margarites in western Crete. Implements of cheese manufacture such as the tarachtis, a whisk-like stirring tool (Fig. 5:10 and Fig. 11), were frequently made of pear wood. The tyrokomos (Figs. 10 and 12), a carved rectangular frame used to support cheese baskets over the cauldron, and the T-shaped stirring tool known as dioiisos (Fig. 5:11 and Fig. 9) were also made of locally available types of wood. Low stools (skamnakia) made of tree roots (koutsoures), frequently of plane or oak wood (Fig. 5:11), were used for sitting around the indoor and outdoor hearths.

1. Hearths built of three upright square stone slabs lined with clay

2. Stone beds and benches covered with thyme-filled mattresses

3. Coppe cauldrons for cheese and mizithra preparation

4. Cheese wheels aging on wooden and packed earth shelves

5. Wheels of cheese in the naturally refrigerated storage area

Goatskin sacks for the storage of mizithra

7. Sheep bells hanging on the walls

8. Cheese baskets stored on shelves and the tops of walls

9. Table and chairs

10. Wooden stirring tool fashioned like a whisk

11. Wooden tools for cheese processing: wooden frame and T-shaped stirring tool

12. Stools made from tree roots

13. Pan of coarse salt

14. Entrances to corral with prickly shrub closures

15. Natural shallow, laminar limestone terraces encircled by the corral walls

16. Enclosed porch area of mitato, with raised roof allowing for air circulation

17, Stoneblock with carved cylindrical depression for the milking can

18. Shelves built into the walls of the mitato

The corral (mandri) of the mitato was divided into two parts (Fig. 5:15). The holding pen, located in this plan to the west of the mitato building, was used to contain the herd before milking (Fig. 7). The limestone walls of the pen and the larger corral were often topped with-thick layers of dried prickly shrubs including thorny burnet, known locally as astivida, that kept the sheep from jumping out (Figs. 5, 6). The entrances to the corral (Fig. 5:14) were also blocked with high movable piles of prickly shrubs. The corral frequently included a large oak tree for shade and embraced the eroded rock face of Mount Dicte (Fig. 4), which appeared within the corral as a terraced floor of bedded limestone layers (Fig. 5:15). At the doorway between the holding pen and the corral was a large stone block set into the ground, with a carved cylindrical depression to hold the milking can (Fig. 5:17 and Fig. 7).

The Pastoral Cycle

For each shepherding family, seasonal existence in the Lirnnarkaro mitato was complemented by life in the metochi, or landholding, which consisted of olive trees and a house in the lowland and/or coastal areas of Crete. From roughly April through the beginning of November, the Limnarkaro shepherds remained in their mountain locality. In November they began their annual trek down the rim of the Plain of Lasithi to their landholdings, either to the area of Chersonesos on the north coast (via the Aposelemis River valley), to the southern part of Crete (in the areas of Tsoutsouros and Myrtos), or even to central Crete (the Pediada; see Fig. 2).

Numerous marketing trips to Herakleion (Fig. 15), during which cheese and mizithra were traded for needed household items, were a part of the yearly shepherding cycle. The economic status of the Limnarkaro shepherd was dependent in part on the traders (emboroi) in Herakleion who set prices for cheese, mizithra, wool, and even hides which were sent on to tanneries. In some cases, instead of dealing with traders, the shepherd might directly provide milk for the dairy or milk-shop owners, wool for saddle-makers, and hides for craftsmen. The success of the olive crop in each family’s lowland holdings also determined the quality of life in the upcoming year. At the mitato, a kitchen garden watered by means of the pole and bucket lever (gerard; Fig. 16) supported the family. Fields of grain (primarily barley) planted in Limnarkaro, with the addition of olive oil brought up from lowland holdings, formed the foundation of the annual diet.

The Products of Shepherding

While wool as a commodity is less well-documented, cheese was a significant export from the island of Crete, both in the Byzantine period (Tsougarakis 1988:278-282) and during the Ottoman domination (Triantaphyllidou-Baladie 1988:202-203), although in both periods the White Mountains of western Crete were cited as the major production area. In the 19th and early 20th centuries in the Dictaean Mountains there were two main dairy products of shepherding: wheels of cheese (kephatotyri) and the liquid form of cheese known as mizithra. Yogurt in quantity might also be made, especially in March, April, and May. In addition to these, wool and meat were also produced, the latter being consumed by the shepherd and his family primarily during holiday periods.

Wool was used at home in the production of rasoto, the thick waterproof cloth made for the shepherd’s cloak (known locally as raw or rasidi). This cloth was woven by the women of the household and was stamped by foot by the men of the family for long periods in a combination water-filled wooden basin (gouvelos) and support frame (katergosa). Wool was also sent down to Herakleion (roughly an eight-hour trip) for processing and use in industries such as saddle-making.

Maintenance of the herd, which ranged anywhere from 250 to 1000 animals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, required that the animals be watched carefully on a daily basis. In the mountains, the herd (kopadi) grazed freely through the predominantly gangues landscape, led by the shepherd or a member of his family. From the end of January through May—the period of heavy cheese production—the sheep were milked twice a day, and thereafter only once a day. The rutting period ran from June through mid-July, with the birth of lambs in November and December. Dead and dying sheep were often carried down the steep Poros gorge separating Limnarkaro from Lasithi and were deposited on the scree build-up at the base of the gorge where they served as carrion for the griffon vulture (Gyps futvus) and the Lammergeier or bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), both of which nested on rocky ledges above.

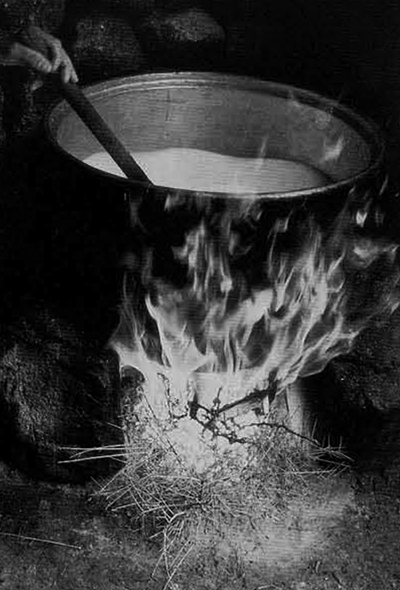

The pressures of cheese production involved the processing of the milk as often as two times per day. Heads of cheese represented substantial income for the shepherd (tsopards or voskos), who could manufacture circa 10 2-kilogram wheels of cheese plus 15 kilograms of mizithra from a total of 100 kilograms of milk (the holding capacity of the largest cauldron, shown here in Fig. 9), which had been produced by milking about 250 sheep. With this herd size a sum total of roughly 1200 to 1300 wheels of cheese could result from a heavy season of approximately 150 days duration.

Cheese Production

To produce cheese, the shepherd gathered wood and dried shrubs, chopped firewood (Figs. 5 and 8), and set the cauldron on the hearth. The milk was poured in, the fire lit, and the liquid (oros) was heated. Approximately half a kilogram of salt was added while the liquid was stirred. A watery mixture (pitia) containing rennet (an enzyme) from the stomach of a ten-day-old Iamb was then added to the milk, and the fire was banked. The cauldron sat untouched for one-half to one hour, frequently covered with a wooden lid.

Once the cheese had curdled, it was stirred with the whisk (Fig. 11), and the curdled material was gradually gathered by hand (Fig. 10) into a mass that was pulled out in handfuls and pressed into the cheese baskets (Fig. 12). This was repeated until all of the cheese had been collected and the remaining liquid could be reheated. By pressing down on the filled basket as hard as possible, the shepherd removed liquid from the cheese and shaped it. The cheese in its basket was placed again in the heated liquid to “harden” its shape. Removed once again from the cauldron, it was pressed, taken out of the basket, perforated with a small wire to allow the passage of all remaining moisture, rolled in a pan of coarse salt which had been pounded in a mortar (havani), and was then returned to the basket. (Prior to WW II large spheres of coarse salt were brought up to the Lasithi area by traders from Herakleion.) The cheese sat inside the basket on a shelf for one day, first pressed on one face (to retain the pattern of the basket base; Fig. 13) and then on the other. (According to some, these cheese baskets originally had distinctive patterns, and the shepherds could order their own designs.) Finally, the cheese was turned regularly as it aged for twenty to thirty days on shelves inside the living!working area of the mitato. Its ultimate resting place was the cold storeroom (Fig. 5:5) where it remained until it was transported down to market in Herakleion.

Mizithra, the second cash product of the Dictaean shepherd, was made from the liquid remaining in the cauldron after the wheels of cheese had been produced. The leftover liquid was reheated, and a small quantity of whole milk which had been set aside was added. This curdled over the fire to a loose, liquid form of cheese (resembling cottage cheese) and was gathered up with a wooden or tinned copper spoon into cheese baskets made of reed (kalama) strips lined with muslin cloth (searopana). The mizithra dripped for one day in the basket, was placed in a metal container (teneke) for two days, and was stored for approximately one month in a goatskin sack (askos; Fig. 5:6 and Fig. 14) before it was sold in the Herakleion market.

The liquid (cHoumas) remaining in the cauldron after mizithra production was poured out into carved stone or wooden troughs known as gournes, which were situated in the immediate area of the mitato. This liquid was drunk by the herd and was considered to give strength to the sheep. The cauldron was then cleaned with boiling water using a scrub-brush made of thyme branches was TIM 41. hearth was dumped outside of the mitato, frequently in the same area over a period of time, resulting in a buildup of hearth debris.

Implications for Archaeology

Killen’s reconstruction (1984) of the Linear B sheep tablets at Knossos has defined a widespread Bronze Age system of shepherding across the island of Crete, a fact that accords well with the importance of shepherding in more recent pre-mechanized periods. In addition, there exist hundreds of small Minoan sites in highland Crete, such as the Late Minoan Faros site (Watrous 1982:52, No. 39) at the entrance to the gorge leading from Lasithi to Limnarkaro, or the Early to Late Minoan habitation site of Katharo (Watrous 1982:49, No. 33) in the mountain plain of Katharo adjacent to Limnarkaro (Fig. 2), at an elevation of 1200 m. (Until the second half of this century, the Plain of Katharo served as the primary summer grazing area for shepherds from the mountain villages of Kritsa and Tappes, a role similar to that of Limnarkaro for Aghios Georgios.)

The spatial distribution of these Minoan highland sites and the occurrence of Linear B tablets containing flock and wool counts and listings of po-me (shepherds) and tu-ro (cheese) (Ventris and Chadwick 1973:572, 588) suggest that shepherding, consisting of wool!textile production and probably cheese production, was a primary element of the Minoan economy in addition to olive and grain cultivation.

If a site such as Katharo were ever excavated, the foregoing description and other systematic studies of traditional shepherding and its material components could easily serve as guideposts in the analysis of archaeological remains from similar environmental contexts within the Aegean. Likewise, they would help in the elimination of archaeological interpretations that are simply not viable. If the traditional maintenance of domesticated animals in great numbers is to prove valuable for Aegean archaeologists in their study of the economy of Bronze Age Crete, both the social and cultural context of shepherding (e.g., Herzfeld 1985; Black-Michaud 1986; Bates 1973) and its material correlates must be elaborately recorded without prejudice toward one form of information or the other.