- Tikal Temple 1.

- Group 7F-1 as it looked in its later years of use, after several re-buildings and structural additions, each inaugurated by the interment of an important man on the center line of Str. 7F-30. Strs. 7F-35 and 36 probably housed servants who catered to the needs of the people living in Strs. 7F-29-1st-A and 32Ist-A.

- Group 7F-1 as it looked i its later years of use, after several re-buildings and structural additions, each inaugurated by the interment of an important man on the center line of Str. 7F-30. Str. 7F-35 and 36 probably housed servants who catered to the needs of the people living in Strs. 7F-29-1st-A and 32-1st-A.

- The Tomb of Ruler A, beneath Temple 1.

When dealing with a complex society, whether your own, that of the Maya, or any other, scholars generally adopt one of two approaches: they look at the society from the top down, or from the bottom up. Although there are exceptions, historians, in their fascination with the doings of kings or other ruling aristocracies, have favored the “top down” approach. Anthropologists by contrast, with their traditional interest in what is going on at the “grass roots,” have tended to view things from the bottom. Ultimately, both approaches are necessary, because the interests, activities and lifestyles of governing elites are apt to differ from those of the common people. Thus, to understand a society solely in terms of what is known about its privileged classes is likely to be misleading. Equally true, though, is that the lives of people at the “grass roots” are profoundly affected by decisions made by those who hold power over them; so an understanding of the culture of “the masses” requires a reasonable understanding of elite culture as well.

If historians have often been criticized for paying insufficient attention to the “common people,” so have anthropologists for ignoring those who wield power in society. From this standpoint, Maya archaeologists have been somewhat unusual among anthropologists. Until fairly recently, they paid scant attention to what was going on at the “grass roots,” concentrating instead on major temples, palaces, and monuments having more to do with the affairs of ruling dynasties than with the lives of ordinary people. The Tikal Project was one of the first to devote “equal time,” as it were, to the bottom as well as the top of ancient Maya society.

Thus, while researchers like William Coe, Christopher Jones, and Peter Harrison added immeasurably to our knowledge of “elite culture” at Tikal. Through their study of monuments, royal tombs, funerary temples, and palaces, others such as myself, Marshall Becker and Dennis Puleston were providing the necessary information on culture at the “grass roots” of Tikal’s society.

One would suppose that glyphs would have little to offer to the study of the lower classes. After all, a main concern of Maya writing was with “dynastic bombast,” as rulers sought to justify their right to office through descent from previous rulers, to glorify themselves through the assumption of grandiose titles, and to link events in their reigns with important astronomical events. Thus, as we began our investigations of Tikal’s rank and file, we thought little of hieroglyphic inscriptions, concentrating instead on extensive mapping, excavation of houses and adjunct structures such as family shrines in virtually all parts of the city and beyond, the investigation of associated burials, and the study of underground storage facilities, or chultuns (sec articles in Expedition 7 [3]). As it turned out, inscriptions were important to us in ways we never expected.

Glyphs and Social Organization

My own awareness of the importance of hieroglyphic inscriptions could he checked against written records. The prospects were particularly exciting in view of the poor preservation of some skeletons, for which it was difficult to estimate age at death. Already, I had picked up hints of a difference in life expectancy between those buried in tombs and those placed in simpler interments, as well as clear indications that tomb principals were generally taller than other males who lived at Tikal. Both differences are expectable in class structured societies, and the opportunity to achieve greater assurance about the apparent age differential was something of a windfall.

Another hypothesis developed out of our work on burials was that of a strong patrilineal emphasis at Tikal. Not only were males invariably the subjects of the royal tombs in Classic times (A.D. 250-880), hut in other burials, males were usually more richly supplied with pottery vessels than were females, and their graves were more likely to be placed in favored locations, as on the center lines of shrines or in house platforms. Thus, glyphic evidence fir patrilineal succession to rulership was welcome confirmation of our thinking.

Further involvement with the glyphs came with work in a group of structures 11/4 km south of Tikal’s Great Plaza. This Group 7F-1 was the site of the University Museum’s first excavations by Coe and Broman in 1957, with later work by Becker in 1963 and myself two years later. What attracted Coe and Broman’s attention was the presence of Stela 23, on which they form an understanding of Tikal’s demography and social organization, took root with Jones’ identification of the three Late Classic rulers A, B, and C, and of the tomb beneath Temple 1 (Fig. 1) as that of Ruler A (see Expedition 6 [1) for a description of this tomb). By then, I was analyzing all the human skeletal material from the site, so 1 was pleased that my diagnosis of sex and age at death of tomb principals

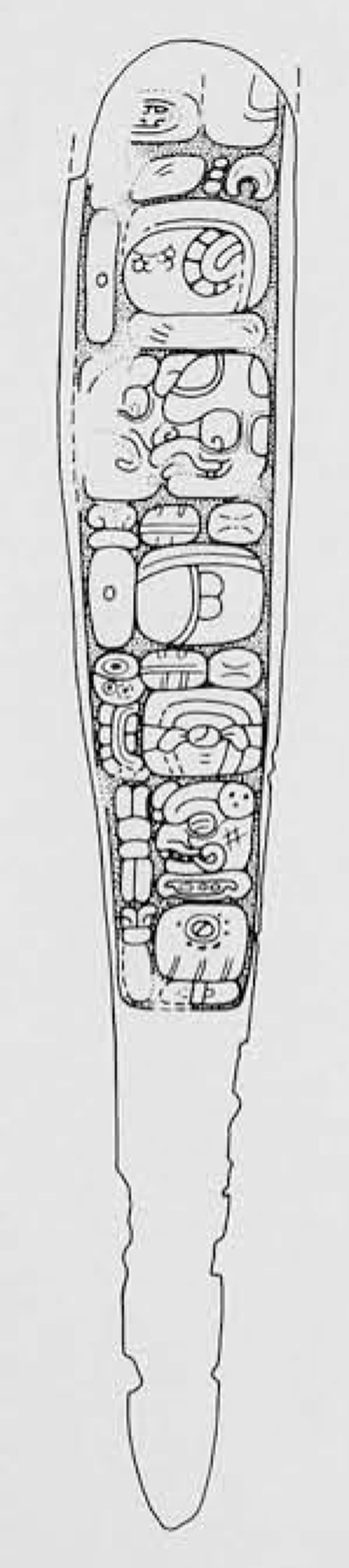

focused their investigations. Becker’s work in two shrines on the group’s eastern edge revealed a series of burials on the front-rear axis of each, beginning with a tomb (e.g., Fig. 2) comparable to those of the “royal cemetery”—that is to say, the Great Plaza and North Acropolis—at Tikal’s center. Richly equipped with red pigment, jade jewelry, spondylus shells, stingray spines, eccentric flints and obsidians, polychrome and alabaster vessels, not to mention two human sacrificial victims, the tomb is particularly noteworthy for its inclusion of the skeleton of a quetzal bird, an extraordinary jade mosaic death mask (pictured on the cover of the National Geographic Society’s The Mysterious Maya), and a painted inscription on the back wall reminiscent of that on the wall of the tomb of Stormy Sky, an important ruler of Tikal who died in 9.1.1.10.10 (A. D. 457; see Expedition Vol. 4, No.1), The date recorded in this other tomb seems to be 9.4.3.0.0 (A.D. 517), a date earlier than the interment itself, but one which is repeated on Stela 23 and also Stela 25, another monument found but a short distance (244 m ) southeast of Group 7F-1.

My own excavations sought further information about the original settings of Stelae 23 and 25, as well as about the other structures in the group. In addition to uncovering more axial burials in the shrines, including another with glyphic information (a carved bone on which a manikin head title and the Tikal emblem glyph are decipherable, Fig. 3), I was able to establish a residential function for other structures, and work out a history of architectural alterations to those structures, many of them correlated with axial burials and alterations of the shrines (Figs. 4, 5).

Dynastic Reconstruction

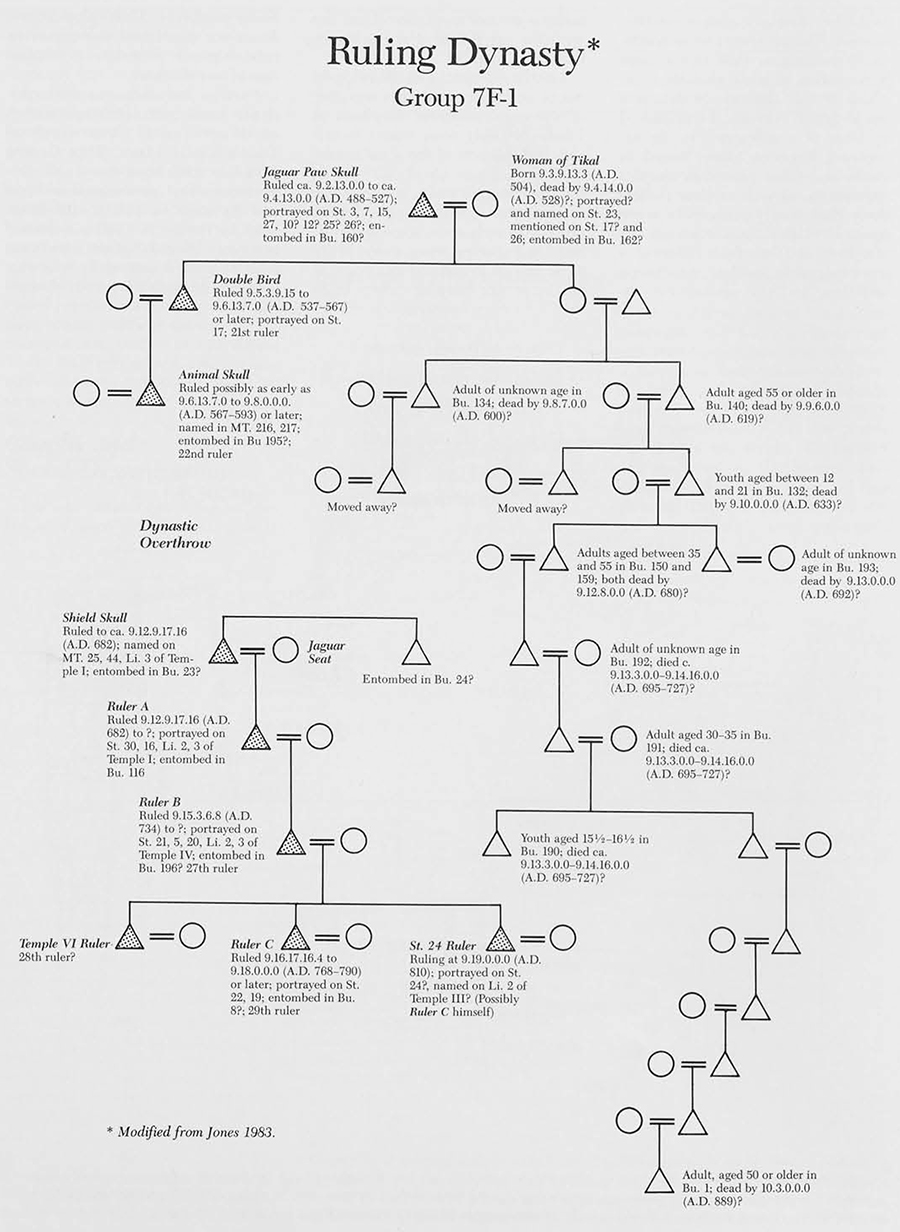

When attempting to write up the final report on Group 7F-1, I found myself at a loss to account for the presence of the tomb and monuments, although that it was some sort of elite residential group seemed clear. It was at this point that Clemency Goggins pointed out the connection of the tomb, as well as the burial with the carved bone in it, with Tikal’s ruling dynasty. She further suggested that the man in the tomb was the one portrayed on Stela 25, and husband to the woman—Woman of Tikal—portrayed on Stela 23. On the basis of other information—including “vital statistics” on Woman of Tikal from Stela 23, I was able to identify another of the “shrine” burials as possibly that of Woman of Tikal herself. To make a long story short, I was then able to arrange the shrine burials into a hypothetical genealogy of occupants of Group 7F-1 from founding to abandonment (Fig. 6). The sequence of events that Goggins and I envisioned was one in which a ruler was deposed and possibly murdered (her idea), whereupon his widow had him buried in royal splendor even though the usurpers would not permit his entombment in the royal cemetery. She herself died while work proceeded on her husband’s funerary shrine, causing some alteration of the architecture in order to accommodate her burial. Their descendants occupied the palace Woman of Tikal had built for herself, but before too long, her son was restored to power, probably moving back to the center of Tikal. A daughter, however, seems to have remained behind (subsidiary figures on Stela 23, one of which is a female, suggests that Woman of Tikal had two offspring, a reason able probability considering she was dead by the age of’ 30). Her descendants continued to live in Group 7F-1 up to the very end, burying their adult males in the larger of the two shrines whenever their relatives at the center were out of power, but burying them elsewhere otherwise.

When I first tried to understand events in Group 7F-1, the reconstruction of Tikal’s dynastic history I had to work with was Clemency Goggins’. This has since been revised by Jones, in the light of Which I have reviewed my original scheme to see whether it still works and indeed it does. According to Jones’ genealogy of the Tikal rulers, Woman of Tikal’s husband was a man whose name we know as Jaguar Paw Skull, and there is no reason why the adult skeleton from the Group 7F-1 tomb could not have been his. On the basis of the tomb pottery, his death probably occurred ca. 9.4.13.0.0 (A.D. 527). The 9.4.3.0.0 date in his tomb is at the time, or just after, Woman of Tikal underwent her first menstruation, which leads me to suggest that this may have been when their marriage took place. She was considerably younger than her husband, having been born in 9.3.9.13.3 (A.D. 504), by which time he was already 16 years into his reign. When Jaguar Paw Skull died, their son, Double Bird, could have been no more than 9 years old; more likely he was only about 5. His date of inauguration, 9.5.3.9.15 (A.D. 537), is ten years after Jaguar Paw Skull’s presumed demise in 9.4.13.0.0.

At this point, the name of a “mystery ruler” surfaces. His name, Curl Head, shows up briefly in 9.4.13.0.0, the year in which we have our last reference to Jaguar Paw Skull. No fewer than five dates were recorded in that year, suggesting that something important was happening. There is one other mention of Curl Head, on Stela S at 9.3.2.0.0 (A.D. 497). Missing on this monument is the Tikal emblem glyph as well as the names of Jaguar Paw Skull, who was ruling at the time, and Jaguar Paw Skull’s father, the previous ruler, Kan Boar. A parentage statement lists Bird Claw as Curl Head’s mother, which is also the name of Kan Boar’s mother. What we seem to have here are all the ingredients of political intrigue: a younger half-brother of Kan Boar (same mother, different father) who is a pretender to the throne after the death of Kan Boar. Late in life, either he had Kan Boar’s successor assassinated, or he took advantage of Jaguar Paw Skull’s natural death and the youth of that ruler’s legitimate successor to seize power himself, banishing his rivals from the center of power. Being well along in years, he ruled for no more than a decade before he died, whereupon Double Bird was able to restore the rightful line of succession until a later dynastic upset occurred.

The Lower Classes

The reader may be wondering: how does all this relate to the “grass roots” of Tikal’s society? The answer is: it provides us with a model to test against data from lower class residential situations. Glyphic evidence has permitted the reconstruction of dynastic genealogies to which the sequence of royal tombs can be related. Glyphic evidence has also assisted in the construction of a plausible, if hypothetical genealogy for the occupants of the burials in Group 7F-1. The same conjunction of burials with periodic architectural alterations is seen, though on a far simpler scale, in lower class residential groups (identified as such on the basis of architectural contrasts with upper class houses, simplicity of associated burials, and lack of exotic or material belongings in general other than those of obvious “everyday” utility). In lower class households, where we have adequate control of construction sequence, and where we have recovered most, if not all, of the male burials present, it is possible to generate genealogies which are consistent with age at death of the individuals involved, which are consistent with the dating for the burials and concurrent structural renovations, and which do no violence to demographic expectations with respect to such factors as age at marriage, reasonable age at birth of’ offspring, and the like. (Figures 7-12 present such a reconstruction for one non-elite household at Tikal, showing its probable developmental cycle through time.) What we seem to have at the “grass roots” of Tikal society is a scaled-down version of patterns seen among the privileged classes.

Neat though this all seems to be, I feel compelled to end on a note of caution. It has to do with a well-known and widespread phenomenon: the practice of rewriting history to suit the purposes of those holding power. What is written is official, and what the holders of power do not want known, they suppress or even destroy. My sensitivity to this issue stems from my work on northern New England ethnohistory, where I have seen how the Puritan forefathers adapted truth to their purposes in their writings. Closer to the Classic Maya in time and space is the rewriting of Aztec history in the reign of Itzcoatl. At Tikal, there were certainly times when dynastic records were “erased” by breaking monuments in half, gouging out whole inscriptions, and mutilating faces. It should not he forgotten that the purpose of inscriptions was aggrandizement of the rulers—perhaps to an impossible extent. It should therefore be a concern in the future to determine how much and how often the Maya altered facts, to make them conform to political expectations.