Between 1931 and 1933 workmen under the direction of Jotham Johnson labored for the University Museum at a Roman site not far north of the Bay of Naples. The ancient Romans knew the town as Minturnae and many entered its gates as transient guests en route to resorts, further south, for the heavily traveled Via Appia passed through Minturnae before crossing the river Liris not far from the seacoast.

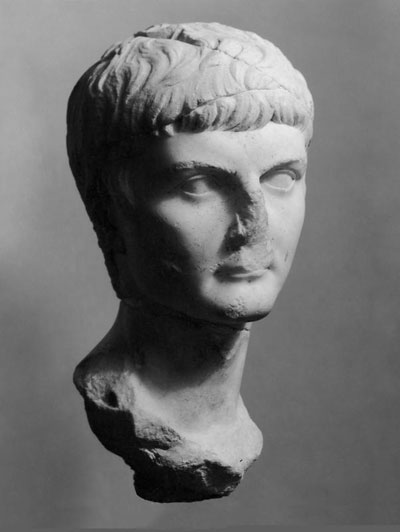

During the excavations, men digging in the remains of temple “B” uncovered fragments of a marble bust which when assembled produced a fine portrait head. The physical characteristics of the most important family in the Roman empire are easily recognizable in the broad forehead, the delicate but definitive chin, and the thin almost pursed lips. He was a Julio-Claudian, so called by reason of descent from both the Julian family of Caesar and the Claudian family into which Livia had married before becoming the wife of the emperor Augustus. The children of the imperial family were Livia’s by her first husband, Tiberius Claudius Nero. At first the members of the expedition believed the portrait bust to represent the emperor Tiberius. This belief was later disproved by comparison with other portraits of this unfortunate ruler. However, the features are obviously of someone closely related to Tiberius. Once all comparative material has been studied only two choices seem possible. The portrait is either that of Tiberius’ brother, Drusus the elder, or of the latter’s son Germanicus. Unfortunately Germanicus so closely resembled his father that it is all the more difficult for us to identify statues of him today. On coin portraits his name provides identification, but the artist had little scope for showing any noticeable difference between the features of Drusus the elder and those of Germanicus. Therefore we must be satisfied with the knowledge that the marble head now displayed at the University Museum reveals to us the facial appearance of one of these two men.

However, only a portion of the story is told. A complete personality must be explained. What kind of men were Drusus and his son?

In 38 B.C. the beautiful and intelligent Livia Drusilla was divorced so that she might marry Octavian, the future emperor Augustus. At the time she had one son, the four-year-old Tiberius, and was expecting another child. Soon after this second marriage she gave birth to Nero Claudius Drusus, so named after his real father. Better known as Drusus he received full measure of care and affection from his stepfather. At the age of twenty-two he was married to Antonia the younger, daughter of Marcus Antonius and Octavia, sister of Augustus. Antonia supervised a happy home and bore Drusus a daughter and two sons, Germanicus and Claudius, the latter destined to become emperor of Rome.

Drusus and his brother were at the complete disposal of the emperor Augustus who was intent on remodeling the government and life of the Roman world. One year after his wedding, Drusus was sent into the Alps where he won his first victory. In 13 B.C. he was made legate of the Three Gauls, and because of his military acumen he was selected by Augustus to lead an invasion of Germany in 12 B.C. Within three years he had planted Roman standards beside the river Elbe, strengthened the Roman fleet in the north, and constructed a canal connecting the Rhine with the Zuyder Zee. In September of 9 B.C., at the age of 51, he died in camp, after having been thrown from his horse.

And what of Drusus’ son, Nero Claudius Germanicus, who was born in 15 B.C.? Germanicus had a pleasing personality. All Romans were anxious to transfer to him the love and admiration which they had held for his father. At six years of age he was left fatherless and at nineteen he was adopted into the family of his uncle Tiberius, thus being placed in line of succession to the throne. In the next year he married Agrippina the elder, daughter of the emperor’s friend Marcus Agrippa and Augustus’ own daughter Julia.

In A.D. 13 Germanicus was sent to command on the Rhine where he successfully suppressed a military mutiny on the death of Augustus. Because of his popularity and military success, Germanicus’ soldiers offered him the throne. Suspicious, the emperor Tiberius immediately recalled him to Rome and dispatched him to the eastern provinces of the Mediterranean in company with an imperial spy. Here Germanicus suddenly became ill. At Antioch he died, firmly convinced that he had been poisoned by the order of Tiberius.

Commemorated in stone, Germanicus or Drusus today gazes down the halls of the University Museum.