When in 1966, it seemed likely that an expedition from Sydney might one day undertake archaeological excavations in the Greek island of Andros, I extended a visit there in order to investigate the present-day pottery situation. If local potters were still working, any investigation must yield useful information about clay sources and types, which should enable us to make a distinction among the excavated material between imported and locally produced wares. A knowledge of traditional methods of clay preparation, forming techniques, fuels and kilns also seemed likely to be rewarding, since there might well have been little change in the island since the introduction of the kick-wheel and the appearance of the village potter in place of the older household tradition. Just what changes there have been, of course, only excavation can show. I was also concerned to see the role of the potter in the community he was working for—the extent to which he was affected by changing demand, to what degree his individual creativity could express itself within the comparatively rigid framework of a learned craft. Finally the pots themselves: how they are used, when and where, how much they cost, what they are called. Such information is an unbelievable luxury to the archaeologist, and he seizes eagerly upon it in the hope that even if it is not directly transferable to the prehistoric situation it will lead him to a more enlightened approach.

It took a surprisingly long time to locate any potters at all in Andros, for my first discovery was that the bulk of the domestic pottery still used in the coastal towns and villages was imported. Such is the topography of the island with its rugged mountainous interior and numerous harbors that communication by sea with other islands or with the neighboring mainland region of Euboea is often easier and cheaper than communication, still often by donkey or mule, with its own mountain villages. One potter, Panayiotis Kozanitis, still survives and works in the village of Amolocho, high in the northern mountains, but he now supplies only his own village with pots instead of sending them down to Gavrion on the coast. One reason seems to be that the Euboean potters of Chalkis are geared to a far greater output, with power-driven wheels and coke-fueled kilns, than the local potters with their kick-wheels and brush-fired kilns; and the Euboean potters are then able to send their products direct by caique to the island ports. Evidence from other islands in antiquity suggests that this Euboean domination of the pottery trade may have occurred at other times even before the mechanization of the industry there. They may always have been cheaper and more easily available than the local products because of the ease of sea transport. Probably they were also considered preferable, for the clays of Andros are red and full of mica, whereas the Euboean clay is light in color and appears much finer. However, this question needs further investigation.

It took a surprisingly long time to locate any potters at all in Andros, for my first discovery was that the bulk of the domestic pottery still used in the coastal towns and villages was imported. Such is the topography of the island with its rugged mountainous interior and numerous harbors that communication by sea with other islands or with the neighboring mainland region of Euboea is often easier and cheaper than communication, still often by donkey or mule, with its own mountain villages. One potter, Panayiotis Kozanitis, still survives and works in the village of Amolocho, high in the northern mountains, but he now supplies only his own village with pots instead of sending them down to Gavrion on the coast. One reason seems to be that the Euboean potters of Chalkis are geared to a far greater output, with power-driven wheels and coke-fueled kilns, than the local potters with their kick-wheels and brush-fired kilns; and the Euboean potters are then able to send their products direct by caique to the island ports. Evidence from other islands in antiquity suggests that this Euboean domination of the pottery trade may have occurred at other times even before the mechanization of the industry there. They may always have been cheaper and more easily available than the local products because of the ease of sea transport. Probably they were also considered preferable, for the clays of Andros are red and full of mica, whereas the Euboean clay is light in color and appears much finer. However, this question needs further investigation.

The main imported shape is the stamnos, or narrow-necked two-handled water jar, often decorated with a white-painted squiggle or flower on the shoulder which was characteristic, I knew, of the work of Vasili Sotyrko at Chalkis (Euboea). In spite of the cheapness and availability of other materials like plastic and aluminum, and the steady extension of piped water throughout the island, the stamnos retains a limited use even in the towns because it keeps water cool by evaporation. I heard that a caique full of pottery had recently unloaded at Chora, probably from Chalkis, and I found these imported stamni in shops at Chora, Gavrion, and Batsi. There were also in a small Chora store some attractive rounded jars, again said to be imported from Chalkis, glazed inside and halfway down the outside, used for storing cheese in brine. I found later that the two Andros potters made the same shape, a bournies, also glazed inside to prevent evaporation, but less attractive. In addition to these pleasant utilitarian pots there was in the main pottery shop in Chora a selection of the heavily ornate, brightly colored prestige ware of Athens—mostly flower pots and vases, some inlaid with fragments of looking-glass for more eye-catching effect.

The main imported shape is the stamnos, or narrow-necked two-handled water jar, often decorated with a white-painted squiggle or flower on the shoulder which was characteristic, I knew, of the work of Vasili Sotyrko at Chalkis (Euboea). In spite of the cheapness and availability of other materials like plastic and aluminum, and the steady extension of piped water throughout the island, the stamnos retains a limited use even in the towns because it keeps water cool by evaporation. I heard that a caique full of pottery had recently unloaded at Chora, probably from Chalkis, and I found these imported stamni in shops at Chora, Gavrion, and Batsi. There were also in a small Chora store some attractive rounded jars, again said to be imported from Chalkis, glazed inside and halfway down the outside, used for storing cheese in brine. I found later that the two Andros potters made the same shape, a bournies, also glazed inside to prevent evaporation, but less attractive. In addition to these pleasant utilitarian pots there was in the main pottery shop in Chora a selection of the heavily ornate, brightly colored prestige ware of Athens—mostly flower pots and vases, some inlaid with fragments of looking-glass for more eye-catching effect.

Eventually I was able to track down the two surviving local potters, Kozanitis of Amolocho and Nikos Loukataris of Strapuryes, as well as many tales of other Andros potters now dead, or moved away, or engaged in other occupations. In the course of this enquiry I came to understand how clay had survived as a material of primary importance for the last five or six thousand years in this island, as in other Mediterranean islands—probably nearer eight thousand years—and how just as surely it is now due for demotion to a subordinate position. Apart from its cheapness and availability, it has positive qualities in the cooling of water, and in thermal shock resistance, that make it particularly suitable for water storage- and carrying-vessels in a community living around a single spring, and for cooking pots where they are used over direct heat, like charcoal. When glazed inside, of course, it is impermeable, and ideally suited to the storage of those typical island food sources—cheese in brine, olives in brine, fruits in syrup, oil and honey—but this technique came in comparatively recently in ceramic history. Before its discovery the outer surfaces, rather than the inner, of such liquid storage vessels were rubbed and polished to cut down evaporation. It is not simply that cheap plastics and aluminum are displacing clay, for both are inferior in these respects. More significantly the needs of the villagers are changing as a result of two major innovations, piped water and power, and different qualities in containers are required. There is no longer a need for rows of water storage pots, to be filled each day; and electric stoves need metal cooking pots with good conductivity. It is instructive to observe the process of this new technological revolution, most rapid in the wealthier sections of the coastal towns. The poorer groups there, and the isolated villages away from the main routes, still have a real though dwindling need for pottery. Moreover, almost every urban household still keeps one water jar, just to ensure cool water; and some traditional items like cheese or fruits in syrup are often kept in traditional glazed pots even in the more ‘advanced’ households. Such a situation is a salutary reminder to the archaeologist of the dynamics of cultural change.

Before the war, I was told, every village had its potter; and even fifteen years ago there were at least four at work in Andros. One lived in the south, at Korthi, and I gathered was from Siphnos, whither he later returned. Siphnians are traditionally potters, and quite often work away from home. Two worked just outside Chora—Loukatris of Strapuryes, who still makes his living by potting, selling some of his wares in Chora as well as in his own village, and George Kalerakis of Koumani, who died some ten or twelve years ago. The fourth was Kozanitis at Amolocho, now nearly seventy and coming towards the end of his working career. I sought out the potteries of the Siphnian at Korthi, and of Kalerakis of Koumani, finding them fast disappearing. The Korthi pottery had been remodeled as a farm building, and there remained only a few sherds, and a fire-reddened patch in a wall where the kiln had been removed. At Koumani, used more recently, the kiln still survived, several old pots, and far more sherds. Such places have an obvious interest for the archaeologist, for they are already archaeological sites with the added value of known data.

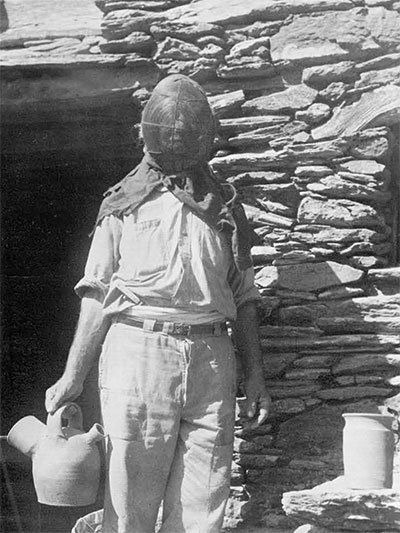

But it was the working potters I wanted to meet, and so walked up into the mountains one day, a four-hour walk, to spend a day with Panayiotis Kozanitis and his family. He was hoeing newly irrigated vegetables near his home when I arrived, and explained that he only made pottery two or three months in the year, in May, June, and early July, since winter was too cold and in summer he grew vegetables. Also there was less and less demand for pottery even in this isolated village, for the general Aegaean drift away from the villages had operated drastically here in Amolocho, and few of the several hundred houses were now occupied. Later, when we went to his pottery workshop, he pointed across the valley to two villages in the distant range, and commented that he would no longer be bothered to carry his wares over there, to load up himself or a donkey as once he had, nor indeed did he now sell in Gavrion either. Once too he had made his own white paint—he picked up a chip of limestone from the path as we walked and showed me. Now he bought it from Athens and the old handmill in which he ground it still lay on a shelf in his workshop. Once too there had been a red paint as well as the white he still used.

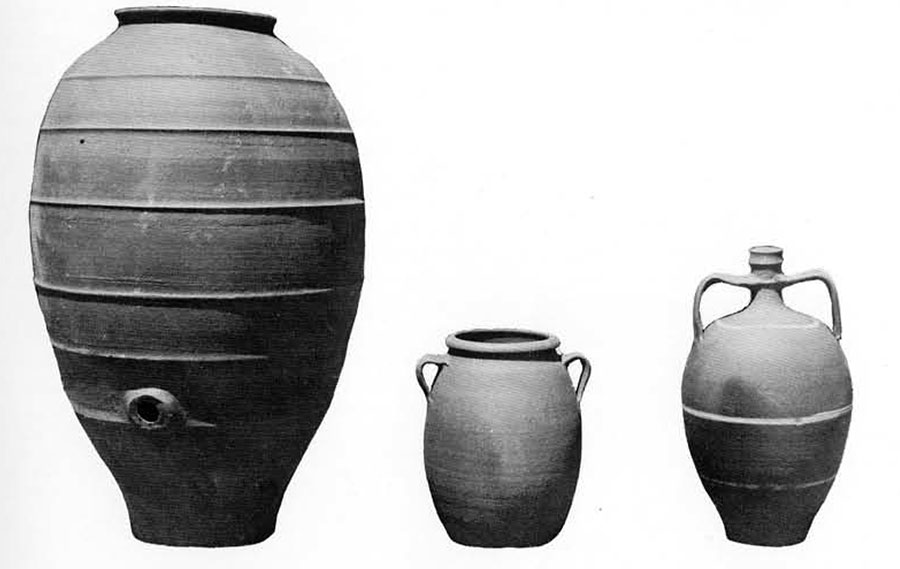

Nevertheless it was apparent from the variety of pots in his own house, as well as in his workshop, that he still made a very wide range of vessels, wider apparently than that of Loukataris. These vessels necessarily related above all to every aspect of food and drink. First, the collection and storage of water, for which there were large and small two-handled water jars (stamni and stamnaki) with narrow necks, secondly smaller handleless pots or carafes (kanati) and wide-necked jugs for decanting and drinking. These were all unslipped or unglazed for maximum evaporation, and there was a good range of sizes for every occasion. Then there were the large glazed jars with medium wide necks (pitheraki), for wine, although Loukataris had far more of these than Kozanitis. Kozanitis said he also used to make little sets of coffee cups but there was no longer any demand.

For serving food a variety of flaring dishes, usually slipped and decorated inside, were made, called lekani. These usually had an emphatic squared-off rim, and a white swirled design inside. They would be used to hold communal pilaff, yoghurt or meat into which each member of the family would dip his scoop of bread. Such dishes could of course be used for other purposes as our own dishes are—I saw quite large ones being used as flower pots, and again to carry washing out to the line. Cooking pots were both slipped and unslipped inside, with either thick tubular handles or two small vertical loop handles. One of them was a casserole dish (called by his tsoukali, and by Loukataris skalia) with lid, slipped inside, the same shape as I saw in many other parts of the Mediterranean and in Attica. Associated with it was a smaller pot with carrying handles, a tsoukaloudha to take food to the fields. Another cooking pot with big tubular handle was the tigani, specifically for cooking almonds. All had rounded bases with roughened exterior surface; and they cooked over charcoal on small charcoal braziers, called phoubou, which were very close in shape although not identical to the braziers now considered to be a specialty of the Siphnos potters.

Finally the food storage vessels. These included a variety of sizes of what Kozanitis called pitherakia, usually slipped inside. One was small and straight-sided, especially used for honey and sweets in syrup. Another was the jar with two vertical handles already mentioned, the bournies, for cheese, and the same form existed without handles for cheese, olives, etc. Most would be covered with a lid, like the cooking pots (kabarki), or more often tied with cloth. To hold the string they had a well-rolled rim.

Much of Kozanitis’ ingenuity and inventiveness appeared to go into his wide repertoire of flower pots and flower vases. A standard flower pot shape in different sizes was usual for the pot-plants, almost always with fluted or finger-indented rim. Vases too were mostly fluted, often with pedestal foot, and sometimes a series of vertical handles. A thick, rather dark green glaze was considered particularly effective in decorating these vases. I saw this green glaze elsewhere on the island, for example a small jug at Batsi, although I could not learn its source. The Chalkis potters also used a dark green glaze on their flower pots. Loukataris of Strapuryes, in addition to flower pots also made a very ingenious watering can. It is not surprising that a comparatively high proportion of a potter’s work should be concerned with plants and flowers, for the Greek villager is passionately attached to such cultivated pot-plants, more often growing nowadays in petrol cans. What is surprising is that it is so obvious a use for domestic pottery that most archaeologists overlook it in their classifications of prehistoric sherds.

Another class of his wares was equally interesting. This concerned bee-keeping, an age-old occupation in the Aegean. Kozanitis made clay beehives, tall bell-shaped vessels with knobs which were set on their sides in rows for the bees to occupy, and which were turned upright for the building of the comb. A similar vessel but less pointed was reported to me from Anaphi with the same function. He also made an odd looking double-spouted vessel with carrying handle called a kapnodoka, a smoke pot. Many other smaller pots in his workshop added to my knowledge of living in Amolocho—a small censer used by the priest, small pots for children, large curved tiles made in an iron frame over a curved wooden mold, and mud bricks made in a square wooden frame.

Kozanitis, I gathered, had learned his craft from his father, who in turn had been apprenticed in Athens. Thus in Panyiotis one might see ultimately an Attic rather than Andriot native ceramic tradition. Yet for nearly a century the needs of the villagers of Amolocho had acted selectively upon father and son, who in addition were cut off from intercourse with the continuing Attic trends. Certainly it would be interesting to compare the two situations today in detail. My impression is that Kozanitis still made many shapes which the more highly specialized mainland potters no longer made and sometimes imported, and of those which could be compared, one or two showed unmistakable deviation in form.

His methods of clay collection and preparation, and of throwing and firing seemed in general similar to those in most parts of the Aegean. He quarried his clay from the hillside behind the pottery, which was built a mile or two from the village on the edge of the mountain. He beat the clay and rock for two hours with a long curved wooden beater (xilo kopano) and then sieved it through a quarter-inch sieve. It was then dropped into the upper of two small wooden tanks, soaked and stirred, then sieved through into the lower tank where it dried out. It was beaten again and stored dry, mixed with water at the time of use. No non-plastics were added. Before throwing he balled the clay, halved it, and worked each half into the other. His wheel, trochos, was a kick-wheel, both wheels of stone. His decorative techniques included the use of white paint applied with a frayed piece of wood or bamboo, used for simple bands, a wavy line, or a series of SSSS. Rims, bases, and grooves he cut with a smooth square wooden plate, with a hole in it and rounded corners. Rims were decorated with different finger touches. Like the other potters I saw in Andros and Aegina he had a single stone-built kiln about six to eight feet in diameter and about ten feet high which he gradually filled. Fuel was the dry thorn bush pushed in at the fire hole, the heat rising through sherd-covered holes in the floor. I could not discover how often the old man fired the kiln—perhaps only once or twice a season by now. The Aegina potter George Garis fires a similar kiln every two or three weeks, with the same thorn bush fuel. Kozanitis, like Loukataris, charged ten drachmae for a large stamnos, five to six drachmae for smaller pots.

The other practicing potter whom I found in Andros was Nikos Loukataris of Strapuryes, a village on the mountain slope above Chora itself, with good taxi communications with the island capital. He was out on the occasions when I called, but I saw his workshop, clay preparation, tanks, kiln, and most of his pot shapes. Living on the one hand in a village which still used water jars in quantity, and on the other within reach of Chora where he sold some of his wares, Loukataris was in a far more favorable situation than Kozanitis, and appeared to work full-time, at least in the summer. The shapes he produced were more standardized than those of Kozanitis, and there were rather less of them. I saw no beehives, but more of the large glazed wine jars, some pierced for a tap. Again there was a good array of flower pots and vases, usually fluted, often with finger indentation.

My time on the island was short, my study limited. Its rewards—not only archaeological—were sufficient to ensure that I will aim at pursuing it further.