I have seen hundreds of descriptions of simple cotton cloths tied around a basket or bowl; offerings placed at the feet of elaborate mummy bundles in tombs of the Paracas/Nasca transition excavated by the native Andean archaeologist Julio C. Tello and colleagues from 1925 to 1931. At that time, archaeology was in its infancy, but Tello’s team worked rigorously to recover, inventory, and transport all artifacts recovered. I have searched for these kinds of fragile offering bundles in the storerooms of Peru’s National Museum of Anthropology, Archaeology, and History and worked with my colleagues to trace their original excavation data. But in all these years, I never have been able to document a conserved textile-wrapped basket, gourd, or bowl.

Partly this is due to early standard practice among archaeologists and museums, in which types of artifacts are typically classified, cataloged, and stored separately. In the mid20th century—as in many museums in the United States and elsewhere—the fragile organic materials stored in Peru’s National Museum lacked climate control and suffered insect damage, leaving many of the baskets and small wrapping cloths fragile, incomplete, and in some cases unrecognizable. Today, storage conditions are good in Peruvian museums, but it is too late for some of the delicate artifacts excavated in the 1920s.

Anthropologist William C. Farabee and Tello were good friends, and each helped the other to locate the Paracas site. Today, the offering bundles that Farabee surface-collected from looters’ back dirt in 1922 restore essential information to Tello’s subsequent large-scale excavations, contexts until now lost to science. Cataloged for the Penn Museum in 1923, Farabee’s small offering bundles were kept largely intact and remained in storage for 100 years waiting for their significance to be recognized and shared.

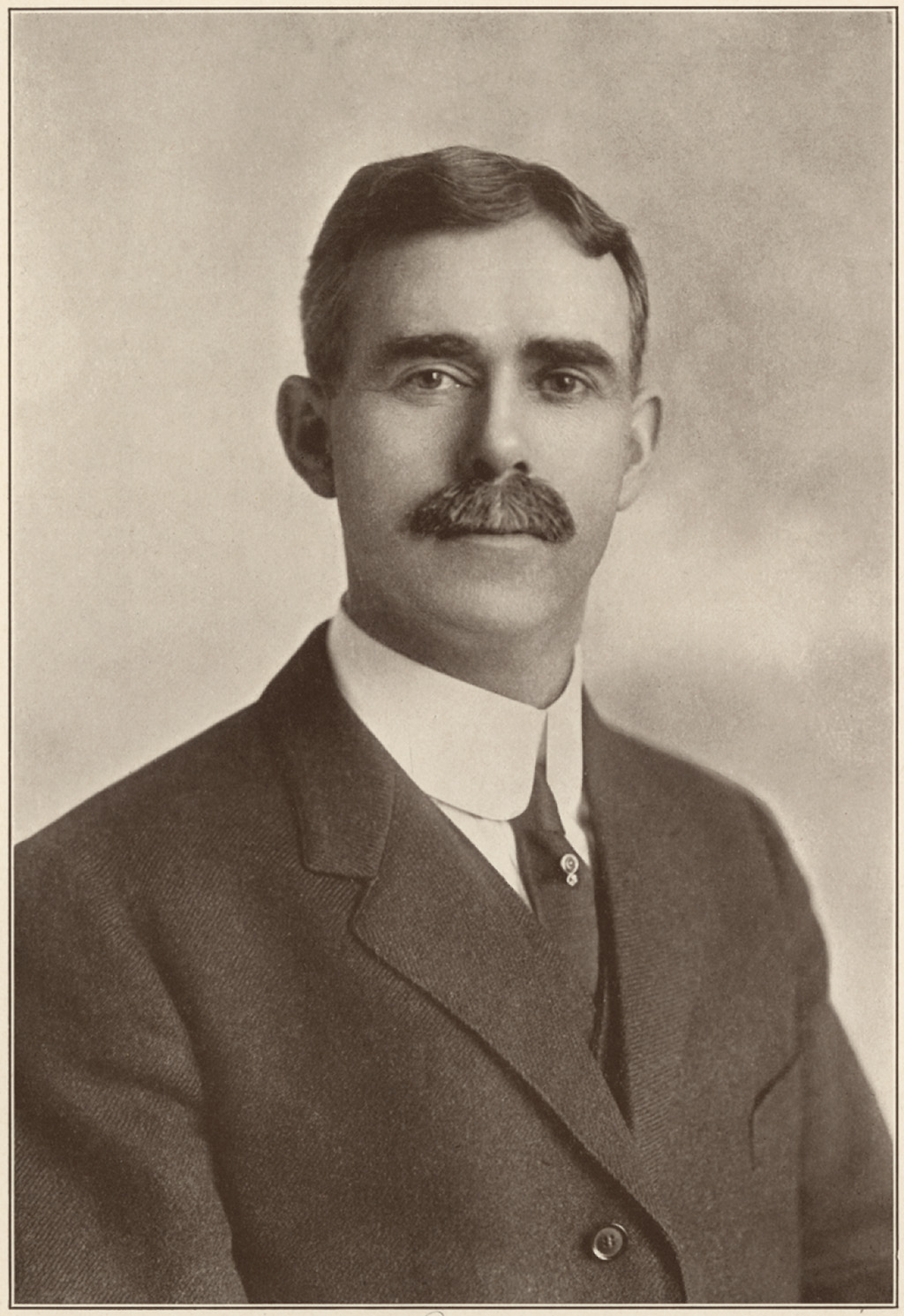

William Curtis Farabee went to Peru in 1922, charged by George Byron Gordon, director of the Penn Museum, with excavating examples of the beautiful ceramics and unique textiles then known as “Nasca.” Farabee was an anthropologist in the fourfield sense, with substantial experience in both human genetic research and ethnography, but without prior experience in archaeology.

However, Farabee could count on the hospitality and logistical assistance of Julio C. Tello, a Peruvian physician whom he had tutored in 1909 when Tello pursued training in anthropology at Harvard. Coincidentally, in 1909, large mantles embroidered in rich colors had been accessioned at the American Museum of Natural History, coming from the Montero collection from Pisco, Peru. As his anthropological perspective on museum studies widened, Tello was asked to offer his opinion on these textiles, and after studies of some British and European museum collections he went on to become Peru’s first national—and Indigenous—archaeologist.

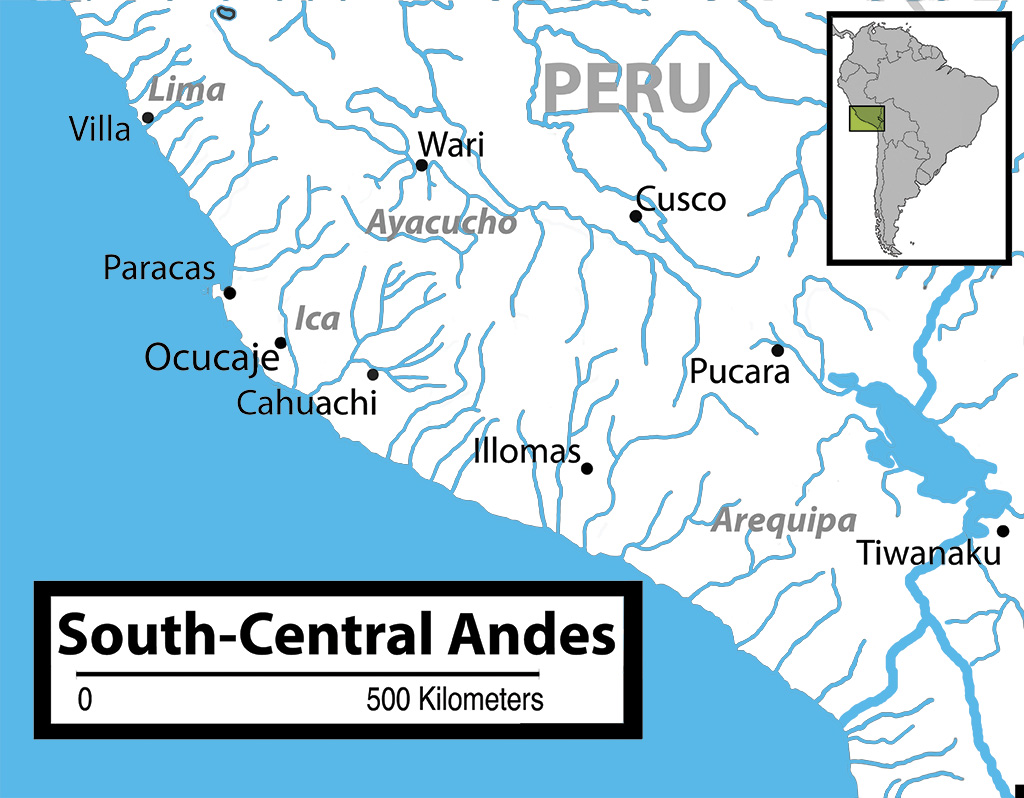

On arriving in Lima with his wife Sylvia in early 1922, Farabee met with Tello, who advised that they should take a steamer to the port of Pisco. Tello provided Farabee with the names and addresses of prominent local citizens in the Pisco, Ica, and Nasca regions who had both personal collections and an interest in supporting archaeological research. Farabee also carried letters asking that officials, landowners, and professionals in the region offer him their hospitality and provide transportation by train, automobile, and horseback.

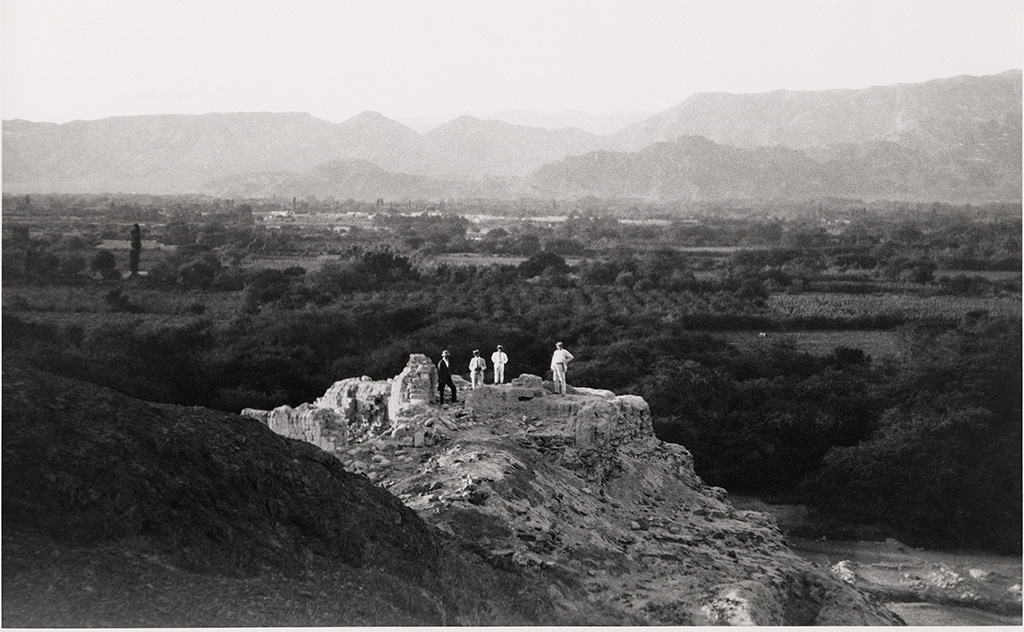

In Pisco, Farabee began meeting with Tello’s contacts, studied the beautifully preserved Inka site of Tambo Colorado, and went south to Ica and Nasca. There, a local contact provided him with skilled workers to conduct excavations at several sites, including significant work at the Inka site of Paredones and the Nasca site of Cahuachi. Upon discovering the elaborate underground aqueducts that bring water to the Nasca fields, Farabee was so moved by this marvel of ancient engineering that he sought them out for drinking water but became violently ill. Travelling by horse and then by car, Farabee barely made it back alive to Ica, where his wife helped him to get back to Lima for treatment.

Return to Pisco and Discovery of the Textiles

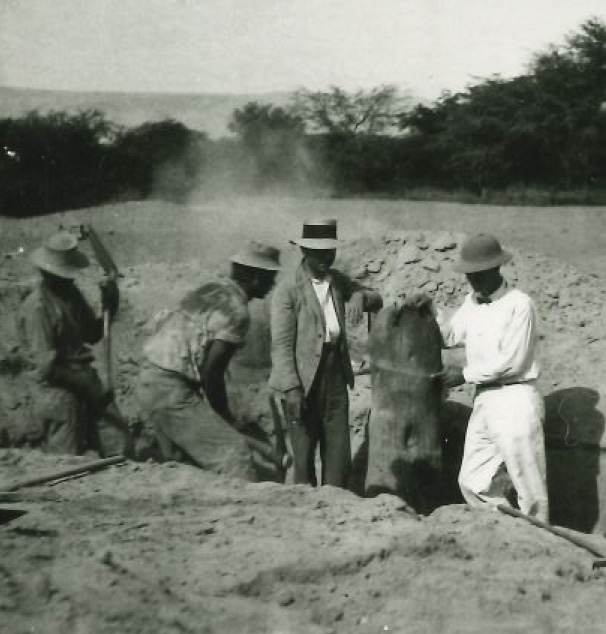

The Farabees eventually continued research and site visits across the Andean region. Six months later, they returned to Pisco. On the steamer, Farabee struck up a conversation with another American, who worked in a booming industry exporting bird guano from the Chincha Islands to be used as fertilizer in the United States. That fellow told him that the small fishing port of La Puntilla, source of fresh water for the ships, was full of locals who excavated tombs nearby. On his arrival, Farabee went to La Puntilla, contracted local workers and excavated a llama cemetery near the Paracas spring. Shortly thereafter, he rented a sailboat, sailed across the Bay of Paracas, and walked up onto the reddish hill they called Cerro Colorado.

At the top of the ridge, Farabee found a disorienting landscape studded with rocky knobs of red porphyry amid sloping windblown sands, covered with looters’ pits and scattered with fragments of mummified bodies and sun-bleached bones. But he also found artifacts unlike any he had yet seen, including fragments of the beautifully embroidered textiles he was seeking. Farabee made a substantial surface collection that day and excavated two simple tombs. He later met with members of the Montero family and with Domingo Canepa— Pisco residents with substantial collections of textiles excavated near Cerro Colorado.

At the time, Tello was working to establish Peru’s first museum of Inka and pre-Hispanic history and archaeology. In 1922, such a museum did not exist, and a presidential dispensation made it possible to transport Farabee’s archaeological collections to Philadelphia, including the objects that he had excavated and those purchased from local collectors. The collection was accessioned by the University of Pennsylvania, but Farabee never fully recovered from his illness and passed away in 1925.

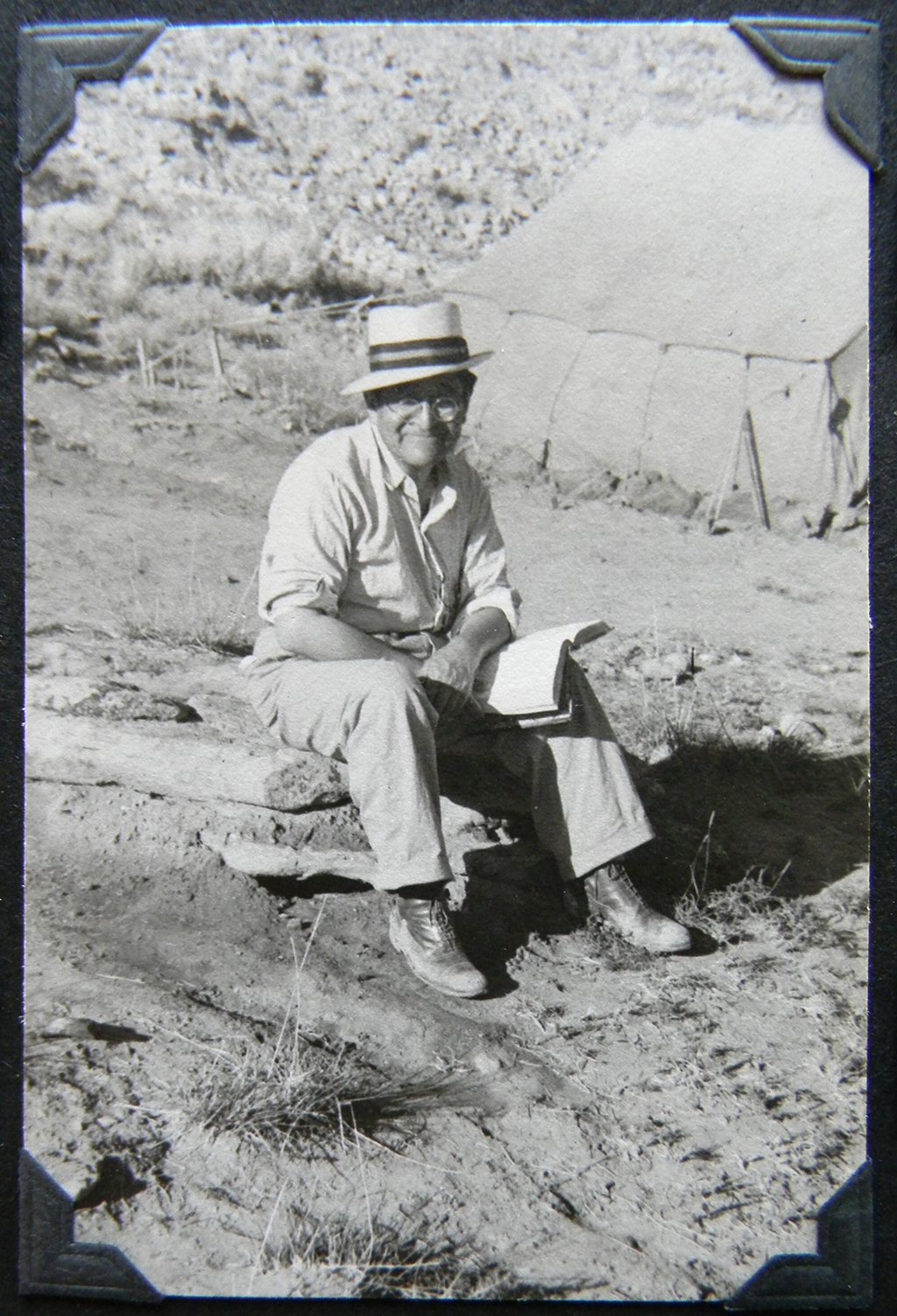

In 1925, Tello travelled to the Paracas peninsula with mutual friend Samuel Lothrop. Stunned by the human remains, textiles, and other artifacts visible on and around Cerro Colorado, Tello suspected that they were not only spectacularly well-preserved, but in some cases over two thousand years old—a hypothesis later corroborated with the invention of radiocarbon dating. Tello returned to Lima and within a month organized an expedition based at the National University of San Marcos, followed later by expeditions of the newly founded Museum of Peruvian Archaeology.

Establishing Paracas

Tello’s research between 1925 and 1930 established the term Paracas, today used to describe many forms of ceramics, textiles, and other artifacts linked to those found at this “type site.” Under Tello’s direction, textile-wrapped mummy bundles were studied on site or brought to Lima to be carefully unwrapped and documented at the museum. Tello described Paracas in the Peruvian press, at international events, and in a 1929 book, his finds suggesting that many of the famous “Nasca” textiles originally had come from Paracas tombs. At the same time, Tello worked in Peru’s congress to establish more effective protection for antiquities.

The Paracas textiles are now famous world-wide and a source of pride for Peruvians. By 1930, Tello’s research and his political efforts to impede commerce in archaeological materials had garnered some enemies. After a military coup toppled the government, Tello was removed from his museum position. His colleagues at the museum went on to publish the first description of excavation contexts and offering bundles at Paracas (Yacovleff and Muelle, 1932). Tello created a semi-private research institute and, by 1933, the Paracas textiles had been relocated there. Tello and his team continued to unwrap and document Paracas mummy bundles, but faced inadequate funding for museum infrastructure and collections maintenance. With Tello locked into a busy schedule seeking private support and investigating sites being looted across the country, most of the Paracas collections sat in storage.

Upon Tello’s death in 1947, his research team organized a review of material excavated on Cerro Colorado in order to produce a posthumous book. They found the objects from Tello’s intensive 1929 collections studies neatly packed and labelled according to their excavation contexts, but were dismayed to find that the voracious tropical insects had eaten away certain types of objects. Basketry and cane objects had suffered the worst: the delicate offerings placed next to a textile-wrapped mortuary bundle were, in many cases, unrecognizable.

As a result, today we know a great deal about some of the beautiful textiles wrapped around the dead at Paracas, but our information on the objects arranged next to the bundle when it was laid to rest in the tomb is largely restricted to drawings and watercolor illustrations produced during the first few years of research by Tello and his team. For a textile specialist, this is not enough: we need to study the raw materials— the spin and ply, the weaves, and other textile structures (and there are many!), employed by the ancient Paracas and Nasca peoples.

While some baskets, gourds, and “colanders” from Tello’s research have survived, the cloth wrappings and original arrangements have been lost. In part, this is due to the standard museum practice of separating objects into categories, which in this case has been exacerbated by the need to protect these particular types of artifacts from the ravaging insects. As Tinteroff has noted, an intact Paracas offering bundle should provide a precise archaeological context, product of the act of gathering, wrapping, and placing these objects together in the tomb. Unfortunately, documentation of particular bundle arrangements is scarce, as early 20th-century photographic documentation of field and museum processes was highly selective.

Artifact Assemblages at the Penn Museum

Farabee attempted full recovery of artifact assemblages and associated organic materials. His 1921 collections from the Paracas site included small offering bundles containing baskets, ceramic, gourd bowls, and foodstuffs, as well as the delicate “colanders” made from canes and reeds, deemed unimportant by the looters. As an ethnographer who had spent time in Amazon basin communities, Farabee recognized the beauty and craftsmanship of these small objects. In 1922, he carefully packed them for safe passage from Pisco to Lima and on to Philadelphia. Moreover, he kept elements of an offering bundle together, preserving their arrangement as he had found it.

Farabee’s bundles quietly sat in storage at the Penn Museum for 100 years, in a temperate climate away from insects that feast on such materials. As a result, the Penn Museum can offer to researchers a piece of Paracas studies that had been lost. While much of Farabee’s collection came from previously looted tombs, these bundles, baskets, ceramic plates, gourd bowls, and delicate cane and reed “colanders” exactly match the contexts later excavated, sketched, and described by Tello’s research team, as well as the artifacts that still exist in the National Museum of Archaeology and History of Peru.

Protected Offerings

Museum Object Number(s): SA3989

Museum Object Number(s): SA3998

Museum Object Number(s): SA3999

Museum Object Number(s): SA3992

Museum Object Number(s): SA4142

Ann Hudson Peters, Ph.D., a Consulting Scholar in the American Section, is a specialist in analysis of textiles and other organic artifacts, with 40 years’ work on late Paracas and early Nasca Andean civilizations spanning ca. 400 BCE to 400 CE in the Pacific watersheds of southern Peru.