Tattooing and body piercing are nothing new. The puncturing and painting of skin have long been expressive forms of social communication in many cultures. Even in the contemporary United States, the reinvention of “primitive” forms of indelible decorations is a way to explore and express identity while resisting established cultural and political norms. However, when self-styled “modern primitives” indulge in body modifications simply because they see them as primal and unchanging, the unique cultural and historical meanings encoded in the alterations become lost in translation.

Contextually considering intentional body modifications presents an opportunity for learning about cultures over time and space. This is the challenge I have taken up through examining pre-Columbian Maya body modifications. I use a bioarchaeological approach in which skeletal remains and their archaeological contexts are considered jointly.

Although it may not be immediately obvious, integrating a bioarchaeological approach illuminates and expands our conception of non-Western writing systems, like that produced by the Maya.

To investigate Maya peoples’ modification of their own and others’ bodies in life and after death, I have considered burials from within and adjacent to the lands owned by the Programme for Belize (PfB) in the Rio Bravo Conservation and Management Area, comprising approximately 260,000 acres. The Programme for Belize Archaeological Project (PfBAP) commenced in 1992; my involvement with PfBAP’s burials began with doctoral research in 1998. The burial sample contains approximately 100 Classic period (ca. A.D. 250–900) burials exhumed by me and other PfBAP researchers, primarily from commoner and elite residences. As was common, these Maya peoples buried their deceased kin beneath and within their domestic structures.

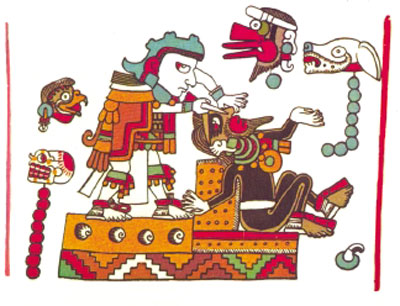

Evidence from artifacts, actual bodies, iconography, and ethnohistories speaks of the many ways in which Mesoamerican peoples altered their bodies. One famous scene in the Codex Nuttall — one of eight Postclassic Mexican screenfolds that contain historical information in iconographic form — depicts the 11th- to early 12th-century Mixtec leader Eight Deer “Tiger Claw” having his septum perforated and inserted with a turquoise noseplug following the conquest of a rival. Piercing of nose, ears, and lips, as well as cranial shaping, tattooing, and dental decoration were also included in the Maya peoples’ repertoire.

The preservation of skin in the Maya tropical lowlands is unprecedented, so consideration of piercing presents an investigative challenge. Artifacts and skeletal evidence from one burial in the PfBAP sample, however, prove informative. In June 2000, colleagues of mine exhumed a Late Classic burial from underneath a residential structure’s floor at the small site of Guijarral. The individual was interred in an egg-shaped burial chamber of irregular cut stones. Despite the highly fragmentary condition of the body, skeletal markers indicated that the tightly flexed individual was a male who died between the ages of 25 and 35. His grave goods included a flower-shaped bone ornament, shell button, and shell disk; the bone ornament was found near his fragmented skull. Based on the location of the ornament, the decedent appears to have worn it in life as well as in death.

For the individual in question, no teeth were modified; if worn as a labret (lip ornament), the ornament would have centered a viewer’s attention at the mouth and affected speech. It is also possible that the ornament was worn in a perforation through the nose, suggestive of a warrior status. Ethnohistorical accounts support this supposition. A.M. Tozzer’s translation of Landa’s Relacion de las Cosas Yucatan quotes the late-16th-century Franciscan missionary Juan de Torquemada’s description of the Maya warriors: Bodies are the original books upon which people inscribed markers of social norms and personal preferences.

The Maya did record their epigraphic writing system in paintings, sculptures, and codices. Advances in decipherment have contributed to reconstructions of sociopolitical intrigue and personal histories from the courtly sector. However, for the rest of society, exposure to and understanding of inscriptions varied. Scribal training was highly specialized, and therefore, restricted to a fraction of society. Most Maya would have communicated cultural knowledge and individual narratives through other channels. Bodies represent one easily inscribable surface for those seemingly “illiterate” members of society.

“They disfigured their faces in order that they might appear ferocious and did the same on the nose and lips, placing in the holes some jewels, worked in gold or silver. This was done to frighten the enemy in war and also for coquetry.”

Regardless of the ornament’s location, this individual from Guijarral did have pierced skin. Such a visible and permanent body alteration would have considerably structured this person’s definition of himself, perhaps in conjunction with his age, gender, social status, and occupation. Reading the signs of past people’s bodily inscriptions offers important and insightful information about the social process and individual experience of constructing identity. In life, it is possible that this individual was a respected member of his community, and the material (and osteological) remains of his burial after death speak to a newly acquired status as venerated ancestor.

With this in mind, what do bodies communicate? Osteological analyses eloquently narrate the dynamic and personal nature of an individual’s life and death. Bodies — changed by social or self-inscription, age, and accident — facilitate archaeological investigations concerned with identity construction. Rites of passage, usually prompted by changes in age, gender, or status, often serve as a space for identity (re)construction. Permanently marking bodies during rites offers visual reminders of a person’s or group’s social transformation. Bodies, then, provide the grounds for how people define themselves, as well as how society perceives this identification.

Pamela L. Geller holds an M.A. in anthropology from the University of Chicago and is currently completing doctoral work at the University of Pennsylvania in anthropology (archaeology). Her research interests include Mesoamerican archaeology, feminist and social theories, and bioarchaeology. In her doctoral project, she highlights the physical body to reconstruct the seemingly ephemeral — ritual practices, embodiment, sensually, and identity. This work draws upon her investigations with the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project (PfBAP). She has also gotten her hands (and various other body parts) dirty on archaeological projects in Israel, Hawaii, and Honduras.

Acknowledgments

In the Programme for Belize, I am grateful to Fred Valdez, Julie Saul, and Frank Saul for offering invaluable support and guidance throughout my ongoing research. I am also appreciative of Jon Hageman and Michelle Rich’s careful attention to detail and documentation during their exhumation of the burial from Guijarral.