Late in August we assembled in the humid oil-bemused town of Benghazi, major city of Libya’s Cyrenaican province. The irrepressible Mediterranean lends its beauty to the natural harbor, along which many of the principal buildings front. Otherwise the city seems overlaid with the dust and paraphernalia of modern construction.

We were five: Prof. Emily Vermeule, classicist, epigrapher, and Aegean archaeologist; David Crownover, commissario and surveyor; William Bertolet, photographer and artist; Fadlallah Abdu Salam, Commissioner from the Department of Antiquities; and the author as director.

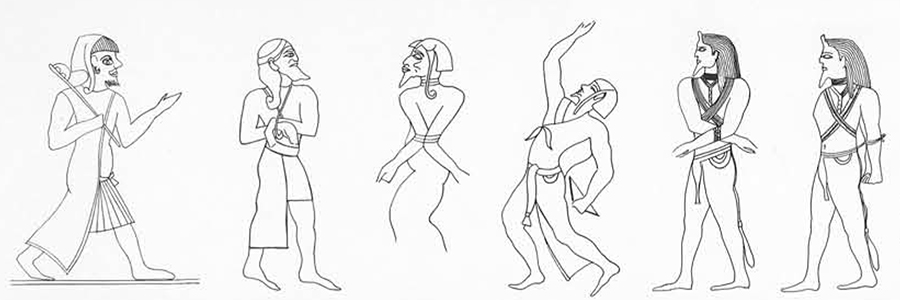

Our principal purpose was to seek traces of Bronze Age Libyans, natives who presumable dwelt in Byrenaica and were described by the Egyptians both in literature and pictorially as early as the Old Kingdom–people whose greatest prominence came in the thirteenth and twelfth centuries B.C. when they were involved in battles with the Sea Peoples and the Egyptians. It is known also that in the Late Bronze Age they acted as middlemen in the exchange of rich materials from Central Africa and products of Egypt and the Aegean. We hoped to find the coastal settlements where this trade occurred.

There are two possible approaches in a survey such as ours: one is to find a geographical location suitable to the requirements of a Bronze Age settlement; the other is to dig beneath the debris of a known site of a later period on the chance that it lies upon an earlier community. We proposed to employ both methods.

A sturdy Landrover was rented through the much appreciated efforts of Essayed Youssef Najjar of the American Embassy in Benghazi. The prophylactic blue of its exterior guaranteed protection against the Evil Eye and more than compensated for its antiquity.

Once again Mr. Richard G. Goodchild, Director of Antiquities of the Province of Cyrenaica gave generously of his great knowledge and resources in helping us to plan a course of action as he had previously in Tripolitania.

The Gebel el Akhdar plateau occupies the bulk of this peninsula, in some places leaving a coastal strip almost ten miles wide, in other places reaching out to the sea itself. We thought first to work the coastal strip south from Benghazi to Ghemines, then to move rapidly around the northern part of the peninsula–where the high cultural centers of Greek and Roman times were located–and finally to investigate in some detail the coast between Apollonia and Tobruk.

South of Benghazi geographic features facilitated our task. Natural harbors were scarce. The only variations in a totally flat and barren landscape were artificial mounds visible on either side of the modern road. Almost always these mounds are named Gasr (literally “castle”). Mr. Goodchild had published a survey of them made some ten years ago, and without aid of excavation had suggested they be dated about the fourth century A.D. He had been concerned with the gasrs in the Ghemines area. As our survey progressed, however, we found they were by no means limited in distribution to southwestern Cyrenaica. Gasr settlements in Ghemines were markedly similar in general lay-out and construction to those in the Gulf of Bomba. We excavated for several days at Gasr el-Arid, thirty kilometers north of Ghemines, to determine stratification, hoping to learn that Libyans under Roman influence had built on top of native Libyan sites. The focal point of each gasr site was a squarish raised fort which commanded a view of some miles across the surrounding plain. A six-meter wide dry moat separated the fort from clusters of large public buildings; at Gasr el-Arid there was a smaller but also raised building across the moat to the north. The central forts provided in later times convenient locations for Italian forts, Arab cemeteries, and sheepfolds. At Gasr el-Arid the surface of the plain for a half mile in three directions was covered with stone foundations, many of which appeared in aerial photograph to be well-oriented buildings. The small rough stone dry masonry walls had tumbled entirely, but a number of the buildings retained their portals, consisting of two vertical cut stone monoliths, often a meter and a half in height. The principal structures and the fort were formed of double stone walls. and the forts were usually faced with large blocks effecting a polygonal sort of masonry over an inner wall of small irregular stones. At Gasr el-Arid on the north side of the fort alone we found more than ten constructed wells, attesting to a population of some considerable size, possibly several thousand persons. Our excavation to bedrock indicated that the site was occupied by a single culture, conceivably subdivided into two building periods in some instances. The pottery recovered showed this occupation to have been in the third, fourth, and fifth centuries A.D. Many of the other gasrs we examined were smaller and in a poorer state of preservation, and sometimes lacked the central fort, but they adhere closely to the date and description of Gasr el-Arid.

Our next sondages were at Euesperides, the original Greek settlement at Benghazi. This perfectly flat depressing site is located behind a salt pan on the outskirts of the city; the unpleasantness is increased by the fact that old Benghazi camels go there to die. We operated in the lower city, which has a very curious appearance; the stones of house and city walls have been quite thoroughly robbed, leaving elevated streets and house floors with trenches between. Bill and Fadlallah drove into the city to recruit workmen and returned with a gang of juvenile delinquents, whom we immediately dubbed “The Sheiks.” Fortunately, after their sharp-witted “boss” had elicited a commission from each of the others, he disappeared and they worked vigorously. Pottery finds were rich and dated from the founding of the city by the Greeks about 515 to the second century B.C. There were two or three levels of occupation above the water table. On the other side of the asphalt road, a modern Arab cemetery covered the Greek Upper City, initially trenched by a group from the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford some ten years ago. The architectural remains there were covered and hence are preserved. The surface collecting of sherds was absurdly facilitated by the local custom of placing large fragments of handsome figured Attic ware on the twentieth century tombs. But again there was no evidence of a Bronze Age habitation.

Further investigations across British Military Beaches to the south revealed no possible anchorages; the only other discernible antiquities were traces of Roman pottery on another elevated Muslim cemetery within Benghazi itself.

En route to Cyrene, we followed the coast road, pausing only to examine several gasrs, until we arrived at Tocra (ancient Arsinoe/Tauchira), a Hellenistic and Roman city of some importance founded in the fifth century B.C. A continuous program of excavation and reconstruction is being conducted there by the Department of Antiquities, and they have established a site museum to house their finds.

We visited Tolmeta (ancient Ptolemais), another beautifully located coastal city; it was admirable laid out according to Hellenistic principles of city planning in the third century B.C., and as late as the fifth century A.D. was made the See of the Bishop Synesius. Elaborately built barrel-vaulted cisterns were constructed under much of the public area in the heart of the city.

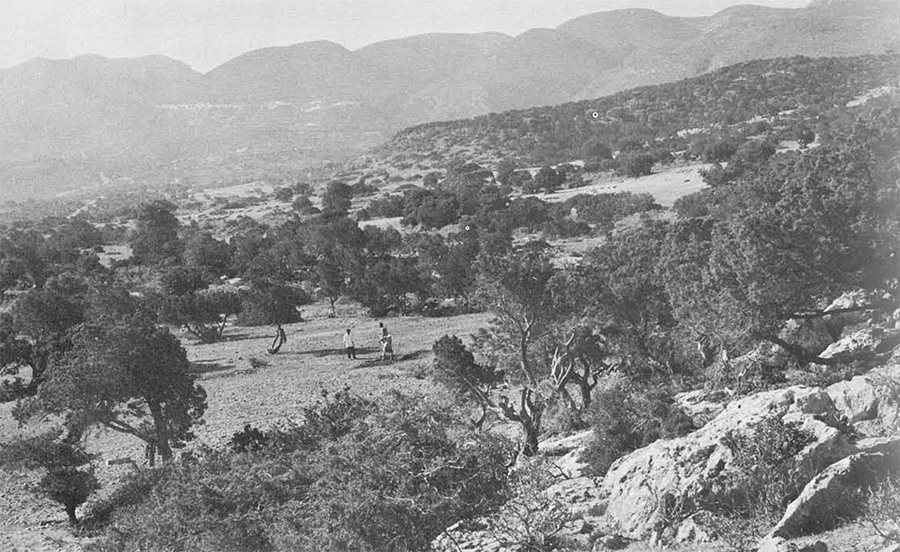

After darkness fell we were aware only of continuously climbing in our ascent to Cyrene (modern Shahat). On the high plateau that is Cyrene the clear fresh air carries a whiff of pungent wood smoke and the scent of evergreens. At dawn, from the summit of the hill, we could see the port of Apollonia, ten miles away. The scope, setting, and architectural concepts of different periods defy description; Cyrene is perhaps best summarized as the North African response to Delphi. Professor Sandro Stucchi of the Italian Mission at Cyrene had excavated some fragments of Late Bronze Age Aegean imports. Since this material had emerged from refuse fill and thus gave no clue to its original Bronze Age location, there was nothing to detain us at Cyrene; yet there to tantalize us was the proof of the period of Libyan history we sought.

At the nearby port of Apollonia (Marsa Suza), the traveller is struck by the simple clear-cut architecture of three Byzantine churches and a very rare palace. In the museum we came across Greek sherds of the seventh century B.C. excavated several years ago by a French Mission. Again, there was no evidence of Bronze Age occupation to encourage further research at Apollonia.

As in the case of Benghazi and Tobruk, the harbor at Derna is modern and was exposed to the vicissitudes of the war in North Africa twenty years ago. Thus our exploratory activities extended from Derna west to Apollonia and east to Tobruk. Our searchers were initially determined by detailed examination of aerial photographs and maps kindly provided by the Department of Antiquities and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

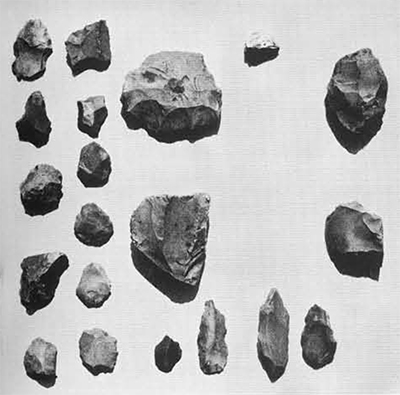

Behind Derna proper, high bluffs flank the steep sides of the Wadi Derna. In the protected depressions of these bluffs the ground was plentifully sprinkled with Neolithic and Bronze Age flints; the agricultural exploitation of the wadi bottom attested to the constant supply of sweet water. Still there was nothing of any period in the way of installations or even temporary shelters on the bare bedrock. The circumstances were essentially the same at Aleut Berruman and Ras bu Madaan in terms of small harbors, spring water, flints, and no other cultural evidence.

The site Latrun, where Mr. Walter Widrig of New York University has in the past few years excavated twin Byzantine churches, was a conspicuously verdant settlement but nothing before Late Roman was evident.

Nearby Ras el-Hilal seemed to offer the most propitious natural surroundings for Bronze Age Libyans. The high promontory was marked by a lighthouse and an extremely interesting Byzantine church excavated by Martin Harrison in 1960. This ras (cape) protected the harbor containing an Italian submarine tunnel, currently a great favorite with smugglers. At a low level on the beach itself a spring of some antiquity even now supplies copious quantities of water. The area around this spring was prolific with flint tools of Neolithic and Bronze Age types. Evergreen-covered cliffs framed several acres of flat land behind the spring, and artificial chambers of varying dimensions were cut into the cliffs themselves. Unfortunately our sondages in this protected area were absolutely sterile and those very near the spring yielded exclusively Byzantine material. Again our artifactual evidence was unsupported by installations or traces of settlement.

Despite our inclination to locate Bronze Age Libyans on the coast, we could not neglect numerous plateau sites up to thirty kilometers inland reputed to be “native Libyan” in character. We examined some half dozen of these; almost without exception the settlement plans and building construction were identical to the “gasr” type. They always contained the ground plans of large public buildings, usually focused around the center, cisterns, and liberal quantities of Late Roman pottery. In several instances, earlier Roman buildings of huge cut-stone blocks, orthostates, and columns were more than half preserved. These plateau gasr sites proved to be one-period settlements and shed no light on the pre-Christian era.

East of Derna another group of meandering wadis terminate in small harbors on the coast. Because of the proximity of this region to the Aegean area, and the prevalence of northerly winds, certain Greek settlement traditions and historical incidents have come to be associated with these sites. The geographical inaccessibility of the locations for tourists and archaeologists has contributed to the persistence of traditions.

Herodotus recounts the two versions of the founding of Cyrene familiar in his day, which after all was only about two hundred years after the events occurred. Limiting ourselves to the facts consistent in both versions, we extract the following: Inhabitants of the Island of Thera (Santorini), suffering from famine, consulted the Delphic oracle; the priests advised them to establish a colony in Libya. Along the way they may have paused at Itanos on Crete to pick up a guide; this murex fisherman, Corobius by name, piloted them to an island off the shores of Libya. Here he remained nearly starving for a year, until he was accidentally re-provisioned by a passing ship. The Therans returned and settled on the island, called Platea, for two years. The island, said to be in area about the size of sixth century Cyrene, proved inadequate for the colonists. Further consultation with the Delphic oracle sent the Therans to the Libyan mainland south and nearest to the island. There they dwelt comfortably at Aziris, reputed to be a delightful location with a river and valleys on either side. After six years, the native Libyans wished to rid themselves of the Greeks and offered to guide them overland and west to the final site of Cyrene. This took place at night so that the Greeks would not be tempted by wonders of Libyan construction and countryside. The exact identification of these classical sites poses innumerable problems and there have been as many speculations.

There are not a great number of islands to the east of Cyrene which might be called “Libyan.” In fact, the first one we examined, Bomba Island, is no longer such, but joined by a sandbar to the mainland. The structures visible in aerial photographs, which had so stimulated our enthusiasm, were gasrs and fairly modern crude circular or rectangular enclosures, probably for flocks. The oldest pottery was Late Roman.

The other offshore island, Geziret el Marakeb, seemed a much more exciting project. While we considered means of water transport and organization for this major adventure, we conducted a search for the site of ancient Aziris. Again we investigated the small harbors at wadi mouths. Many of the desert tracks were virtually impassable for our Landrover and often three blowouts and as many hours were involved in an actual distance of ten kilometers from the main highway to the coast; these serpentine tracks had a road base either of bare pitted rock or thick red dust. The only significant cultural evidence was obtained at the mouth of the Wadi el-Chalig. The natural foundations of a towering promontory were washed by the salt Mediterranean on one side and the fresh waters of the constant wadi on the other. Traces of stone-built city walls, public buildings, and private houses were visible. Strong winds whipping across the headland prevent more than a slight deposit of soil on the rock subsurface. Thus we gathered many bags of pottery, much of it imported from Greece and clearly ranging in date from 600 to 200 B.C. If this site can be accepted as ancient Aziris on all other accounts, it must be admitted that some of the Greek community stayed longer than six years! In a negative vein, even though there is no island off shore, if this site is not Aziris, what tradition exists, in Herodotus’ own lifetime, for a Greek colony of some other name at the mouth of the Wadi el-Chalig?

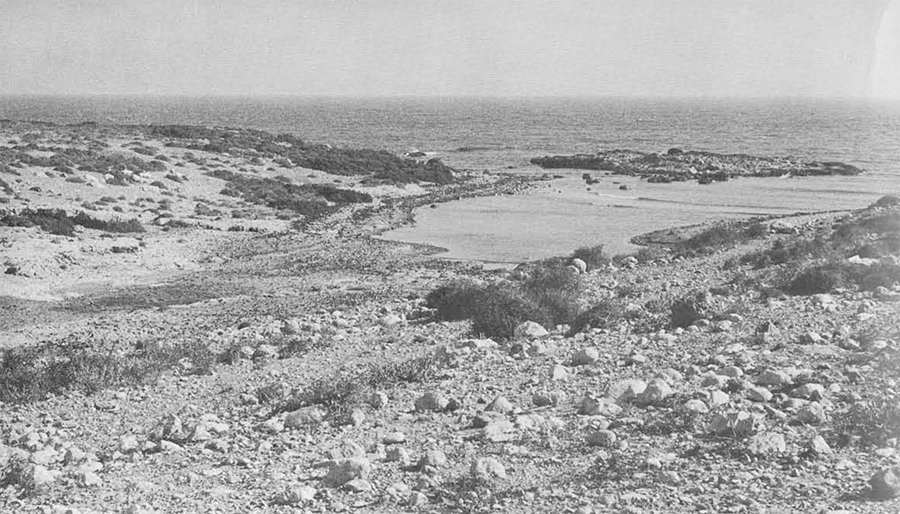

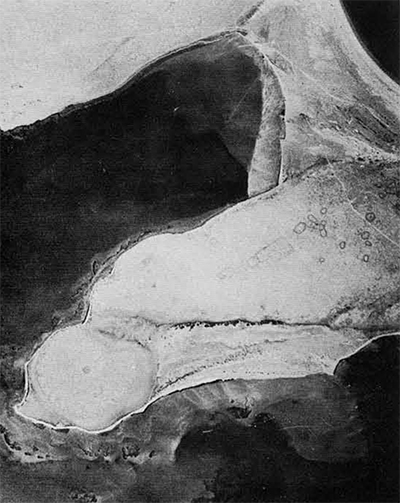

Finally we were ready for the expedition to Geziret el Marakeb (Seal Island on Admiralty charts). We reduced our equipment to essentials and motored to Tobruk, where an enthusiastic and hospitable welcome awaited us in the form of Squadron Leader D. Power of the RAF Station there and fifteen men of the Tobruk Sailing and Sub-Aquatic Club. After provisioning and organizing details, we drove back to the peninsula of Ain el-Gazalla, as yet an uncleared mine field of the last war. We pitched our tents on the point exactly south of Seal Island. The divers had two dinghies with outboards, in one of which they proposed to transport us across the mile and a half to open water separating the peninsula from the island. We wrapped our equipment in waterproof covers and condensed our provisions and emergency supplies to the minimum necessary for thirty-six hours on the barren island, in the event that the small boat should be unable to cross agains rough water and tide at sunset. The RAF had thoughtfully commissioned a helicopter to stand by in case of acute need. After a few hours of repose on the hard ground, we were prepared to embark at “first light.”

Archaeological research and speculation regarding Seal Island can be separated into three phases:

Professor Oric Bates in his exhaustive study, The Eastern Libyans, discusses elliptical and circular enclosures of small stones, and notes “small offering niches” proving them to his satisfaction to be grave enclosures of unknown date. Bates made a brief visit to the island in 1909 and describes circles about nine meters in diameter and 1.15 meters in height with “offering niches” of four stone slabs in the southwest corners or small “chapels” built against the outside. He found no grave pits and noted that five centimeters of soil covered the natural rock. Interiors were nearly void of sherds, but outside there were numerous small fragments of coarse brown ware and common Roman pottery. Bates concluded the Seal Island structures to be purely Berber of pre-Islamic date, reflecting an early and widespread African burial type.

In 1928, Sir Arthur Evans, the famed excavator of Knossos, published his theories of Cretan origins. He discussed the “tholoi” of the Mesara plain, round stone-built burial structures of the Early Bronze Age, and related them in plan and concept to those of Seal Island described by Bates. Evans then concluded that the Cretan round tombs were based on earlier Libyan models.

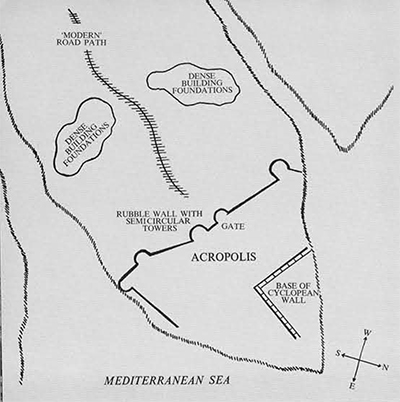

With the exception of several ten-pound fish hauled aboard, our crossing to the island was uneventful. A fifty-meter wide shallow shelf bordered both the island and Ain el-Gazalla peninsula; the greatest depth in the water between was eight meters. On the island were more than sixty generally round circles of small stones, varying from three to twelve meters in width and from one to two meters in height. Some gave the appearance of gun emplacements, but because of their proximity to one another this was impossible. As Bates had observed, they were without pottery; a little pottery (Late Roman to modern) was sprinkled on the surface. We excavated the center of the largest circle and found the suggestion of what may once have been a grave. The scant cover of earth on the surface rock is inadequate to protect anything for long. Our only skeleton was that of a cat outside one of the low doorways. Attempts to locate a source of fresh water on the island were fruitless, although this may not always have been the case. An inscription on a rude grave marked the recent death of a Greek sponge fisherman; they still frequent the waters and there is evidence of occasional camping ashore. We collected an assortment of empty cartridges and military relics, which were identified by the British forces as Italian, British, and American, dating to World War II. Meanwhile the skin divers, working on the protected sides of the island and off the mainland, had recovered an impressive collection of pottery; among others were numerous amphora fragments, some at least as early as the third century B.C.

In the approximate center of the island we fell upon a previously unnoted architectural complex. One of the major buildings of rectangular shape was constructed of small cut stones and divided into three rooms. The raised aspect of another major building led us to conclude it was a temple of sorts; in association there were four large rectangular red stone architrave blocks, with carved Roman decoration. A series of small sondages revealed a white plaster floor in situ and fragments of cream plaster walls. There was no stratification or habitation evidence anywhere.

On the basis of our Seal Island and mainland investigations we were able to evaluate some earlier traditions:

We found no traces of Bronze Age trading posts.

It is most unlikely that Corobius and the Theran settlers would have passed two famine years on Seal Island, which is separated from the constantly visible mainland on two sides by wide shelves and shallow waters. Ain el-Gazalla point by no means fits Herodotus’ description of Aziris, the second colony. Furthermore, the earliest material in both places is Roman. However, the Wadi-el-Chalig mouth, a day’s sail away, could pass Herodotus’ description of Aziris and the material is sufficiently old. We have yet to locate Platea Island.

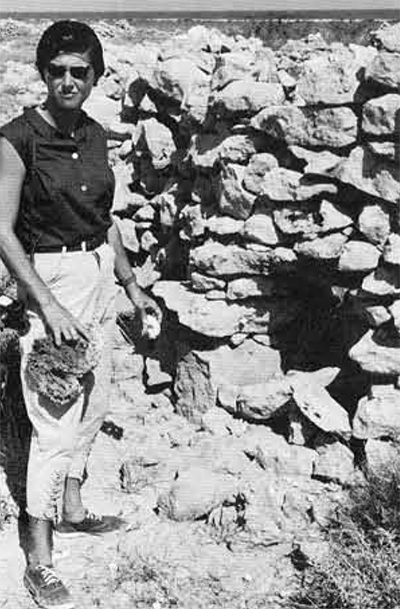

Professor Bates was probably correct in his belief that the Seal Island structures were grave enclosures, and there may well be connections with other African traditions. This past summer’s discovery of sophisticated Roman architectural remains on Seal Island again links the native Libyan and Roman cultures. This serves to enforce certain conclusions reached by Mr. Goodchild in his gasr survey of southwest Cyrenaica, namely that much of the crude stone architecture of forts and primitive settlements could be dated to the Late Roman period of about the fourth century A.D. and later. Our sondages and ceramic evidence confirmed this predicted dating for nearly all the gasrs visited. The material on Seal Island we should then place within the framework of pre-Islamic civilization, perhaps using the third century A.D. as the lower date. Much more of what we saw in Cyrenaica of primitive statuary and rock carving undoubtedly belongs in this same time span and demonstrates a coalescence of Roman and Native Libyan art and tradition.

This “Libyan” culture which we can now date A.D. 400 and later often betrays its true age by indisputable traces of Roman architecture, such as the architrave moulding on Seal Island or the column base carved in the primitive sculptural complex at Slonta. The less prominent “gasr”-type sites invariably produced Late Roman and Byzantine pottery of a common and consistent character. A picture emerges of a surprisingly homogeneous culture inhabiting the fringe of the Gebel el-Akhdar, both on the edge of the plateau and on the lower coastal strip–though never on the Mediterranean shore–and ranging from at least Ghemines to Tobruk. Many of these cultural manifestations were previously ascribed to the Bronze Age population; the people themselves may actually be the descendants of those bellicose Libyans who allied with the Sea Peoples in a force of well over fifteen thousand agains Pharaoh Merneptah about 1230 B.C.

The Egyptian authors describe the Libyan prince as wearing sandals and carrying a water skin. We can only conclude that this is an apt description of a Bronze Age Libyan; he lived the nomadic life of the present-day Bedouin and his skin tent left no architectural traces. From time to time the Libyan tribes encamped in the small harbors where we noted sweet water springs and Bronze Age flints. Occasionally contacts were made in this way with Aegean and Levantine seafarers; in later times Phoenicians sailing from Byblos to the Pillars of Hercules attempted to pass each night in such a sheltered cove.

The distinguishing features of the ancient Libyans are almost entirely limited to perishables of clothing, feathered headdresses, and other ornaments. Since we are now convinced that permanent settlements did not exist for these people, it is useless to seek further in coastal Cyrenaica or along the plateau perimeter. We should rather look back toward the Libyan Sahara. Somewhere between the artists in the Fezzan who painted scenes of chariots, and afterwards camels, and the Mediterranean littoral, lies a great oasis where even Bronze Age Libyans lingered to barter and fill their water bags. A chance find may one day reveal the location and illuminate the culture of the enigmatic Libyan nomads.