Museum Object Number: MS4028

In general we know comparatively little about the life history and personal traits of ancient worthies. The evidence for Menander comes from Greek of Latin writings or from inscriptions and is conveniently assembled near the beginning of the second volume of Koerte’s edition of Menander.

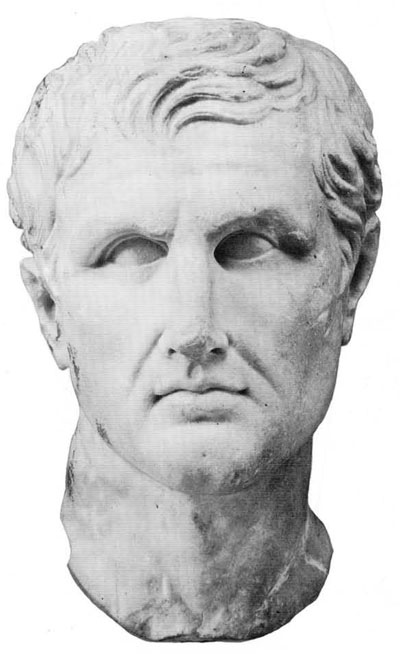

The Suda (Suidas), a tenth-century work of reference, informs us that he was “squint-eyed but keen-sighted mentally and extremely enthusiastic about women.” The word used in Greek for enthusiastic implies romantic devotion, since Plato uses a cognate form to commemorate his own love for his favorite pupil Dion, which was certainly a matter of mind and heart, not physical. I must confess that I never personally observed a squint in the portrait of Menander discussed above, but when I once pointed out this head at the University Museum to a lady who had no special concern with art or Greek she at once exclaimed, “But he squints.”

Dr. Fay’s measurements and photographs prove that there is a difference in the symmetry of the eyes as depicted in the marble. Evidently this may look like a squint to a casual observer. Since a contemporary of Menander, Lynceus of Samos, wrote a book about him, we need not doubt the statement that he squinted. There may have been jokes about it that were recorded in memoirs. The case for attributing this head to Menander is certainly strengthened by the literary evidence for a squint.

I have found very little to add to this one fact about Menander’s physique. He was a great lover and he died at the early age of 50-52, drowned while swimming at Piraeus, the harbor of Athens. He was the son of wealthy and high-born parents. He was nearly condemned in court because of his friendship with Demetrius of Phalerum, the peripatetic philosopher and orator who acted as moderator of the Athenian state for ten years (317-307 B.C.) and severely pruned the excesses of Athenian democracy.

The account given by the Latin fabulist Phaedrus of the first meeting of Demetrius and Menander, is denounced as quite untrustworthy by Koerte. I find it hard to believe that there is not some basis for it. Menander in his plays is indulgent to all well-meaning characters, regardless of poverty, status, or sex. He idealizes the love of good women. It is natural to contrast him with the philosophic moralist and political conservative who limited extravagance by sumptuary laws. In Menander’s play, The Epitrepontes or Arbitration, the chief character Charisius is a philosophic youth who yields to the power of love and becomes a much better man for it. For Menander philosophy was not enough. The heart, too, must be educated in the school of experience.

Let us see what Phaedrus has to say, bearing in mind that he wrote fables, not history. He describes the general rush to pay court to Demetrius and to seek favors from him. Menander came among the last, reluctant visitors who came only because they feared the consequences of not saluting the new leader. Demetrius had read and admired the plays of Menander, but did not know him personally. Menander approached, drenched in perfume, in flowing robes, with delicate, slow, and languid step. The tyrant caught sight of him at the end of the line, and asked: “Who on earth is that effeminante person who dares to appear before me?” Informed that it was Menander, he changed his tone at once and declared: “No human being could be more handsome.” The slow approach of Menander may have been due to weakness in the leg, but that can hardly be proved from Phaedrus. He is interested in the moral: Handsome is as handsome does. Still, there is nothing in the report of Menander’s languid gait. Since this legend is unusual in its personal aspects, those who wish may make what they can of the tale. Menander seems to have done military service as a youth. He was not severely handicapped in war or in lobe, nor did he squint mentally.