In 1947 my father, Frank Reeves, discovered Wolfe Creek Crater, one of the most acclaimed geological features in Australia. Located in the flat plains of the Great Sandy Desert some go kilometers south of the town of Halls Creek in western Australia, it is the second largest known meteorite crater in the world. More than 870 meters across and 50 meters deep, almost perfectry circular, it is believed to have been formed when a meteorite weighing thousands of tons punched a huge hole in the ground.

My father encountered this striking formation while exploring for mineral resources as a consultant for an Australia oil company. He is credited as having “discovered” it because he was the first to map it and comment on its geological composition. In his honor the Smithsonian Museum named one of the minerals of the meteoritic material, now on permanent display, “Reeves.”

The following year my father nearly lost his life in another region of the Great Sandy Desert. He was traveling by horseback and mapping mineral prospects, accompanied by a “half-caste” guide named Billy Dunn, then in his early 30s. Billy was fathered by an itinerant gold prospector who impregnated an aboriginal woman just after she came in from the bush.

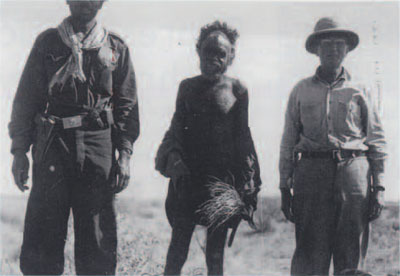

Billy met up with my father soon after the crater discovery. They traveled for four weeks with two aboriginal helpers, eating the “abo” way. This meant snake, grubs, and a host of other interesting delicacies—or so my father said, always telling the story with a glint of tall-tale nostalgia in his eyes. Along the way they got lost and were unable to find water. Disaster was averted by the arrival on the scene of an aboriginal man who was on “walkabout,” carrying only his spear and traveling with his three wives and children. Named Japutu, this man led Billy and my father to a water hole where they were able to make contact with a search plane through smoke signals.

A photograph of my father with Billy and Japutu standing by the plane that found them was the only visual record I had of my father’s storied travels. As a young girl going to school in Perth at the time, the picture made me an anthropologist before I knew what anthropology was. I dreamed about the knowledge that made it possible for people to live on the land and find their livelihood with nothing more than a spear. Where the news media marveled at my father’s so-called discovery of the crater, I marveled at the men and women who lived in the Australian bush and saved my father from what might have been a very nasty ending.

In the summer of 1999 my sister and I met with Billy Dunn to retrace my father’s travels. Billy treated us as daughters. When Billy stopped at the old landmarks, I sensed his excitement and nostalgia and recorded his recreation of the tale of so long ago. What took four weeks in 1948 took us four days.

In the summer of 2000 I will return to the crater and visit the aboriginal communities surrounding it whose members claim it as their “dreaming country,” the land of sacred origins. I will also visit Halls Creek to study aboriginal representations of the land through painting and story telling.

My goal is an anthropological memoir focused on the three men who met in the Great Sandy Desert in 1948. At the time, anthropology was the study of “primitive men” and, like so many of the early anthropologists, my father was serving the interests of European outsiders. Looking back, more than half a century later, everything has changed. Today, aboriginal groups no longer roam the desert as nomads but travel in Land Rovers. Alcoholism—”being on the grog”—is a huge problem. People who “came in from the bush” in the ‘4.0s and ’50s live in isolated communities far away from their “dreaming country” and their “law land.” Anthropologists visit these communities In an effort to reconstruct the life of the past. Yet they neglect to tell us in their books that the life which is represented is no more. Nor do they tell us that their data base consists of aboriginals from different language groups squeezed together in one community in a multicultural hodgepodge trying to preserve some semblance of the traditional and the sacred.

For me, there is a satisfying circularity, mirroring the form of the crater itself, in going back over my father’s footprints in the Australian bush. While my father looked for mineral resources for European exploitation, I want to recapture the imagery that once animated the land but now exists only in stories and on canvas. Perhaps I feel that putting it on paper is the nearest we can get to putting it back where it belongs, in the land and with its people.

There is another circularity in the meshing of lives then and now. In 1999 when I met Billy, I also met Japutu’s youngest wife and two of her children, Doris and Joshua Booth, who were present at that meeting long ago. Today we are all part of the same world, a world that no one could imagine fifty years ago. This merging of anthropology and its object is part of anthropology’s postmodern condition. It is also the subject of my story line.

Peggy Reeves Sandy

Professor of Anthropology