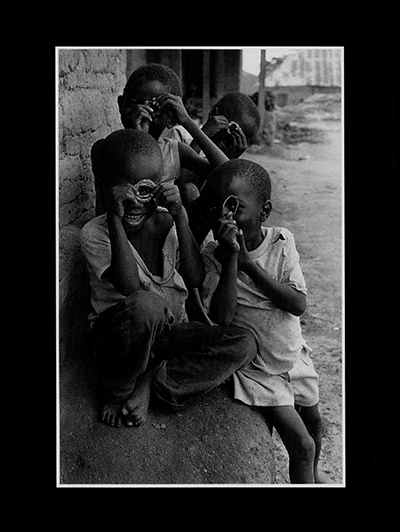

KLH Young Kono boys have relatively few chores to do for their mothers of fathers and they spend most of their time wndering the town in the company of playmates their own age. One of their pastimes in 1988 was following Michael Katakis as he took photographs.

MGK These young boys had followed me for days. I would raise the camera to my eye and take my pictures, I could hear laughing from behind me and quickly turn and they would always scatter, disappearing behind a tree of building. After a few weeks of this dance I turned to the laughter and found these fellows looking at me through their homemade lenses.

Photographs have long been an important tool of cultural anthropologists. A quick survey of the anthropological literature shows visual images being used to provide records of change, to record important events or activities, and to elicit commentaries from informants about performance, costume, or other areas of interest. Increasingly in the last 20 years, however, anthropologists have begun to question the veracity of their visual records and to explore the ways that culture, interests, and personal experience shape the interpretation of visual images. These questions have led to a reexamination of what “documentary” means and how we judge a photograph and its ability to help us understand other worlds (see MacDougall 1991 and Ruby 1991, for example). We have come to realize that photographs and their interpretations often tell us more about the photographer or viewer or, when published, the editor, designer and writer than they do about those who are actually photographed.

The Illusion of the Image

How many times have you heard the statement “A picture is worth a thousand words”? With pictures there is what Michael Katakis has called the “illusion of the image”; one sees what is happening as real and true, and yet that truth can only be an interpretation. John Berger writes (1972) that interpretations of visual images, like interpretations of literature and speech, are shaped by the experiences of the interpreter, his or her culture, goals, interests, and training in ways that remain relatively absent and unexplored. He also writes that ”Them relation between what we see and what we know is never settled” (1972:7). If this is the case then people’s interpretations of visual images will change as their experiences compound in the normal course of everyday life.

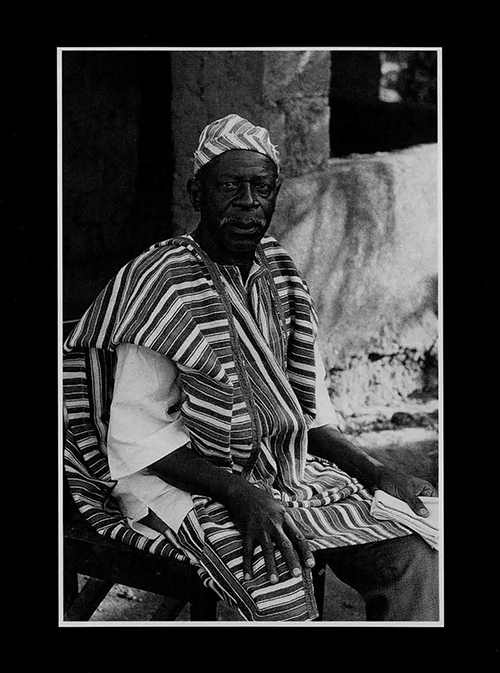

KLH Here you see a man wearing a shirt of locally produced “chief’s cloth.” It is called chief’s cloth because of the thickness of the fabric and the prevalence of indigo-dyed thread in the pattern. This is a portrait of Chief Faiduo, the Chiefdom Speaker (second in command) of Soa Chiefdom.

MGK When I first met Chief Faiduo he shook my hand—his hands were so large they completely covered mine. One of my few portraits Chief Faiduo wearing his country cloth

The ways that experience and background affect the interpretation of visual images were brought home to me after working with photographer Michael Katakis during a field trip to the Kono area of eastern Sierra Leone in 1988. Soon after returning to the United States it became clear that Katakis had made an extraordinary collection of photographs, yet anthropologist and photographer saw the photographs and the potential of publishing or exhibiting them in very different ways. As an artist, Katakis felt that the photographs stood on their own as visual images and that ethnographic commentary should be minimal. Katakis’s stance is an example of what Kratz has called the “family of man” view, which posits that “the humanistic message of the photographs would be obvious, conveying unity within the diversity of humankind” (Kratz nod.). As an anthropologist with a commitment to cultural specificity, I felt it would be a disservice to those photographed to encapsulate them in our world without hying to share some of what is interesting and unique about Kuno history and life. Karp (1991) and Karatz (nod.) characterize these differing points of view as assimilating and exorcizing.

Seen together our positions (Katakis’s reliance on similarity and mine on difference) reflect two diametrically opposed approaches. In their extreme forms each of these positions is problematic. On the one hand, emphasizing similarity flattens out cultural difference in ways that lead to a homogeneous view of humankind. This view cannot acknowledge the existence and thus the effects of inequalities or cultural and historical difference. Emphasizing similarity also leads to the interpretation of what is perceived as different as the representation of marginality, pathology, or dysfunction. On the other hand, emphasizing difference, as my training as an anthropologist seems to foster, has the potential of exoticizing other life-ways to the point that translation or communication between cultures becomes a conceptual impossibility, children and laboring in their husband’s rice fields. The Kono say they migrated from the highlands of Guinea to their present location, probably about 500 years ago. Scholars say this migration probably occurred in the aftermath of the fall of the great Mande empires of what is now Mali and northern Nigeria. (For a more complete description of the Kono see Hardin 1993.)

The Photographs

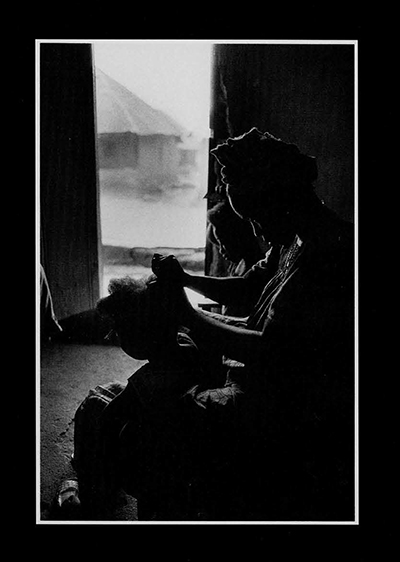

KLH Here a woman is plaiting her daughter’s hair. For rural Kono neatness and beauty signify morality, while a disheveled appearance can indicate insanity and some kinds of illnesses.

MGK I photographed these people because of the light-I love this light; I was really not aware of the people.

We selected the photographs in two ways. Katakis was interested in those that he thought would make the best images for future publication or exhibition. I was interested in presenting a variety of views of Kongo life. We selected 25, although only 10 are included here. (The complete set will appear in our hook Three Voices: Images and Reflections from a West African Town.) Once they were chosen we worked separately as if we were writing captions for an exhibition of photographs, I as an anthropologist and Katakis as an artist. When we arrived in Sierra Leone, we asked Mondeh-Gbegba to add her commentary. We had decided not to share our captions or really discuss the project (except to choose the photographs) until. all three sets of commentaries were completed.

On the following pages you will see the photographs, coupled with the three sets of commentaries. Following the photographs I will discuss how interests and experiences have played into the ways that each of us responded to the images.

Three Voices

When working with Monica Mondeh-Gbegha in Sierra Leone, I began by collecting a life history in the hopes that I would be able to connect some of the particularities of her captions to events and interests that shaped her interpretations. Mondeh-Gbegba is Kongo, although not from the chiefdom where the photographs were taken. She was born in 1955 and completed several years of high school before marrying. Her husband, Daniel, has worked in various capacities with foreign missionaries throughout much of their married life. Together they have seven children. Mondeh-Gbegba has lived in Koidu, the second largest city in Sierra Leone, for most of her adult life. Last spring she moved to Freetown, the capital of the country, to escape fighting between rebel and army forces in the Kuno area. She has passed several certificate courses that enable her to provide various kinds of health care at the community level. Her familiarity with Kainkordu comes from her work over a period of years with a mobile health clinic that traveled to the area once a week to provide treatment and education. In 1992 she and her husband began working to construct Mondeh-Gbegba’s own clinic in Koidu. While she knows many of the families in the Kainkordu area, she knows personally only two of the individuals whose photographs appear here.

KLH Older women spin cotton thread in the afternoons of early evenings when most of their other work is done. Once a woman has enough thread she will engage a amn to weave it into strips that are sewn into blankets, shirts, or lappas (a length of cloth that is worn as a skirt). Here an older woman winds threads from a spinning bobbin onto a larger bobbin for storage.

MGK What attracted me to this woman was her elegance and smile. Also, I loved her glasses-they reminded me of Buddy Holly. As I photographed her I hummed a Holly tune She smiled, but the little boy appeared to be thinking “a madman has come to our town.”

After collecting her life history I asked Mondeh-Gbegba to briefly discuss each image as if she were writing a caption fat a photograph in a book. (I used the analogy of a book instead of an exhibition because Mondeh-Gbegba was more familiar with the book format.) I suggested that she consider the photographs in terms off what they might tell an outsider about Kovno life or what she might want someone to know about the Kovno area. We worked in English. I edited her taped captions (some of which were quite lengthy) to shorten them to a length comparable to those written by myself and Katakis. Is editing I tried to preserve both a sense off her voice, as well as the range of topics she touched on to describe each photograph.

There are several clear patterns in them captions provided by Mondeh-Gbegba. Her commentaries circle around the topics of health care (Figs. 1, 3, and 7), them needs of those photographed (Figs. 1, 3 and 4), and poverty {Figs. 1, 5, and 9). This selection of topics certainly reflects Mon deh-Ghegba’s training as a health professional. To some extent it may also reflect the suggestions I gave her about constructing her captions (what the photographs tell an outsider about Kono life or what she might want someone to know about the Kongo area). Given these instructions, Mondeh-Gbegba’s captions also reveal something about her perceptions o the public she was addressing. In man; African countries Europeans and especial]; Americans are perceived as being wealth; and potential benefactors who might be willing to fund a health clinic, purchase school books or otherwise provide assistance in rural African areas.

Mondeh-Gbegba’s interests in viewing images in particular ways comes out clearly in her discussion of Figure 7. While she knows the woman portrayed personally she does not name her. By saying the woman is just a nursing aide she differentiates herself and her degree of training From that of the aide, She also makes i clear that this is a local clinic rather than government-run enterprise, which further separates Mondeh-Gbegba from them woman in the photograph. In contrast, for Figure 2 (the portrait of Chief Faiduo Mondeh-Gbegba names the person photographed and by doing so associates her self with it powerful member of them community in a way she was reluctant to do with the woman in Figure 7.

Overall, Mondelt-Gbegba, even though she is Kono, presents a distanced view o most of the photographs. While this ma: he somewhat due to my instructions, it is also clear that she is interested in separating herself from most of the scenes of rum life portrayed in the photographs. As am educated urban dweller her life experiences have been very different from those of the farmers found in rural communities such as Kairmkordu. Mondeh-Gbegba’ training and wage employment, for example, alleviate the necessity of doing small scale trading, and while she may halve learned to spin thread at some point early in her life, it is not a practice she continues. She also has very little experience farming. Mondeh-Gbegba tends to depic rural Kongo as poor, and to see local mode of production and ways of doing things as examples of poverty or of the need for medical care and training and other kinds of assistance. By emphasizing the need for health care she not only calls attention to the needs of many rural communities throughout Africa, but she underlines her own particular forms of knowledge and expertise. The interpretive stance of difference aids her in this enterprise. It allows the construction of an image of herself as more like those she perceives to be viewers of the photographs and captions (specifically non-Kono and probably non-Sierra Leoneans, as per my instructions) than those portrayed.

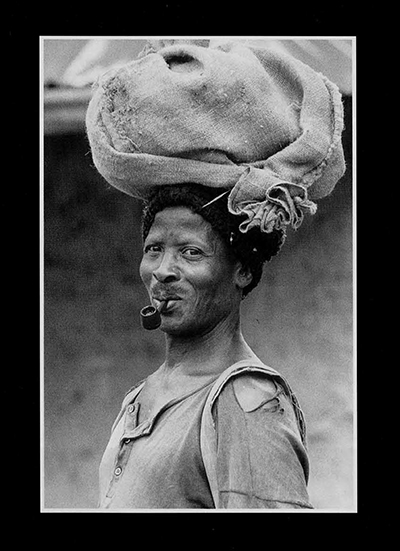

MGK My camera almost photographed this man on its own. His smile and his eyes were so alive and magnetic. He possessed a kind of joy that was radiant.

My own captions to the photographs also present a distanced view, but in a slightly different way and for slightly different reasons. Again, these can be related to personal experience. I was born in the Central Valley of California in 1953. I do not remember a time when I was not aware that there were probably many ways of doing the same thing. I have a suspicion this view was fueled, if not fostered, by the fact that I reached high school as the sixties were coming to a close. I was too young to take an active role in many of the protests of that era, but I certainly grew up well-versed in anti-establishment rhetoric and the search for alternative lifestyles. I started college as an art student but switched to anthropology after my first year, partly because I found the questions that anthropologists ask about value, creativity, and art more intriguing than the practice of art itself, but also because anthropology seemed to provide the perfect arena within which to explore the varieties of human experience. My first trip to the Kono area of Sierra Leone was from 1982 to 1984. I made return trips in 1988 and 1993. Another important piece of the biographies presented here is that I married Michael Katakis in 1987. What bearing this has on the captions presented here is difficult to assess. It did, however, make for more lively discussions of how to publish or exhibit the photographs.

The distanced view that is apparent in my own captions to the photographs comes from a tendency to show how singled actions or scenarios are related to more general cultural patterns. This stems directly from my training as an anthropology the way he picked up a camera and began photographing. Katakis is uncomfortable being pigeonholed as a photographer or artist for he has also published several articles and edited a volume of essays on topics related to current social issues. He has made two trips to Sierra Leone, in 1988 when the photographs were taken, and in 1993 to work further with Monica Mondeh-Gbegba.

When I asked Katakis about his captions, he attributed this tendency to relate his photographs to his own experiences to two influences in his life. As the son of a Greek immigrant he found himself somewhat betwixt and between, not Greek and not American. He sees much of his younger life as a search for similarities between himself and his friends and classmates, in order to deny the differences that an immigrant background often imposes. In later years Katakis has traveled extensively, and these travels have often taken him to places where English is not spoken. His strategy for getting around in such situations is to use pantomime and laughter, concentrating on similarities of gesture and expression to communicate.

The tendency to emphasize similarity also shows up in the kinds of photographs Katakis took. I was struck by the fact that he had no photographs of agricultural labor among his approximately 2,000 photographs. Agriculture is obviously an occupation that is of primary importance to rural Kono. It was certainly part of most peoples daily activities during the months of July and August while he was in Sierra

Leone. Katakis, however, chose not to photograph this dimension of Kono life, probably because he had little basis for understanding it or relating it to his own life.

Conclusions

This article points out some of the ways that background, training, and interests affect the interpretation of visual images. The question remains, however, Whose story counts? It is a difficult position to take, but from the above exploration I can only answer that they all count in some way, because none of them can stand alone. A quick comparison of the three texts for any of the photographs presented here demonstrates this. While all of the stories count, they have drawbacks, but these are only readily apparent within a comparative frame, such as that attempted here. Visual images cannot be viewed free of interest or simply as fact. What becomes important, then, is knowing how to judge an interpretation of a photograph. Ordinarily, when faced with only one caption, we do this by matching the intetpretation to our own expectations and we delve into past experiences to help us decipher a particular image. Knowing something of the biography of the viewer or interpreter suggests another avenue to explore, namely what interests they have in presenting information in certain ways and what kinds of information they have at their disposal to present. Following this approach, viewers may become more aware of the resources they use to interpret visual images and the ways that stereotypical, illusionary, and often inaccurate images tend to outlive their creators and become resources for constructing how audiences think about a certain place or issue.

The last topic I want to pursue has to do with the implications of this work for social science. Anthropologists, in particular, have been exploring the idea of multiple voices as a way of circumventing the problems of bias. Some believe that you get closer to a kind of truth by using several voices or letting the “informants” speak, either by themselves or alongside the researcher. Such productions can he deceiving in two ways. First, no individual can speak for a group. My view of the photographs was considerably different from Katakis’s, just as Mondeh-Gbegba’s view differed from that of someone else I might have worked with. Second, in projects such as the one presented here, there is always someone at the helm and their interests will be apparent, although perhaps subtle, in what photographs are selected, how the editing is done, and how the questions are asked. It does not matter if that person is from the group being photographed. Instead, I would suggest that using multiple voices is an important strategy for developing the tools that allow individuals to question or be aware of the biases inherent in the interpretation of visual imagery or in interpretation in general.

- MM-G People here have come to sell their market so they can buy food. A little boy is buying some groundnuts [peanuts] and beans, a pregnant woman is selling garden eggs [eggplant] and groundnuts so that she can buy rice. People here spread their bags on the ground for their markets. This really shows that they need a health worker to advise them about how to maintain their food. KLH One of the few avenues to cash for rural Kono women is small-scale local marketing. The eggplant,bananas, pepper, and peanuts being sold here are surplus from the women’s gardening. MGK The markets were wonderful places—activity was composing itself around me with great speed—sometimes I was quick enough to capture it.

- MM-G These people are finished selling their markets so they are going back to their villages on foot because no vehicle is available. KLH When the trucks do not run or if people don’t want to spend their money on transport, they walk. Many rural Kono say the worst problem of their lives is the lack of dependable, cheap transport. In their words it keeps them from being able to get produce to market and from being able to get emergency health care. MGK The people walked and walked and then walked some more, often barefoot and carrying heavy loads. I walked this road more times-I stopped here to record the terrain but mostly to sit and rest.

- MM-G This is a village that we do mobile clinics in. We used a hanging stick scale and trousers so we can know the weight of the chid. this is a local clinic and it is just a nursing aide that is running it. KLH This is Agnes Sebba at work in the Manjama clinic. Here she is measuring a baby’s growth. Younger Kono women such as Agnes are beginning to find new ways to support themselves that take them away from the arm work that has been their major occupation until recently. MGK Agnes Sebba was one of the more remarkable people that I have ever met. She worked very hard to improve conditions at the Manjama clinic. I photographed her working with a new patient.

- MM-G This vehicle has come from a village where people meet to sell their markets. The women are finished buying and they are going to their places. KLH A truck on the road to Kainkordu. The driver’s assistants are known as “rally boys.” Young boys dream of becoming rally boys, but few families would encourage their sons to pursue such a life. MGK These fellows came rushing down the moment to take this one photograph. Their expressions of unadulterated joy remind me of driving down Pacific Coast Highway in a convertible with the top down.

- MM-G This vehicle has come from a village where people meet to sell their markets. People come to the villages, buy produce and carry it to Koidu for sale. The women here want the driver to carry their markets to Koidu because they know they will be able to sell there. KLH This truck is passing through Kainkordu on the way to Kamiendo and the Guinea border. (Kainkordu is the headquarters for Soa Chiefdom.) Trucks such as these bring consumer goods to rural Kono and return with produce for the markets of Koidu when the road is passable and petrol is available. MGK I was continually amazed at people’s resourcefulness and determination under difficult circumstances. “Here, I thought, “is transportation that would make a westerner weak in the knees.”

- The Kono pictured in this article live in and around Kainkordu in Sierra Leone.