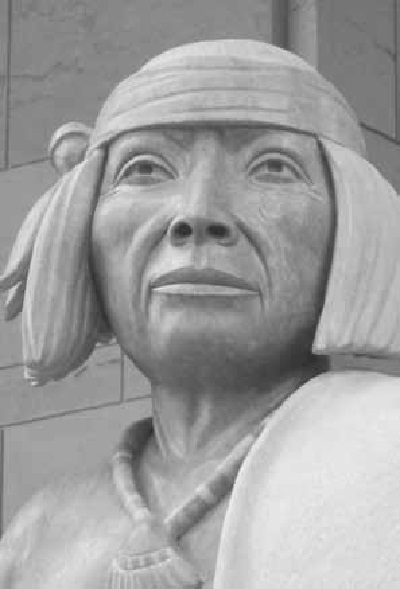

On August 10, 1680, the Pueblo people, along with their Navajo and Apache allies, orchestrated what is arguably the most successful indigenous insurrection against a European colonial power in the New World. The uprising, led by Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo leader Popé, laid siege to and captured the capital of Santa Fe while missions at pueblos up and down the Northern Rio Grande River were burned and destroyed. Four hundred and one settlers and 21 friars lost their lives in the uprising. The number of Pueblo lives lost is unknown. Under the leadership of Governor Antonio de Otermín, the remaining soldiers, friars, and settlers retreated in disgrace to El Paso del Norte (today Cuidad Juárez, Mexico).

Following several failed attempts by the Spaniards to reestablish a presence in the region, a concerted effort to reconquer the pueblos was undertaken in 1692 by Don Diego de Vargas, newly appointed governor of the exiled territory. Vargas initially offered absolution to the pueblos for their sins (i.e. the revolt) if they surrendered and became vassals of the Crown. Vargas’ audacious attempt at diplomacy led many historians to inaccurately characterize his entrada (a journey into foreign lands) as a “bloodless reconquest,” oblivious to the fact that countless Pueblo lives were lost during several military expeditions in his effort to recolonize the region.

Three major centers of resistance to Vargas’ reconquista emerged in the rugged mesas surrounding the Jemez Mountains. Pueblos along the Rio Grande were vacated and refuge communities were established by the Towa in the Jemez province, at Kotyiti in the Keres province, and at Tunyo in the Tewa province. Vargas led major military campaigns against each of these provinces in 1694. Tunyo, the ancestral stronghold of San Ildefonso Pueblo, my home community, was occupied by as many as 2,000 people from 7 Tewa villages. The mesa-top site was the setting of a nine month siege in 1694 during which the Tewa boldly defended the mesa against Vargas and his allies.

The Pueblo Revolt offers a unique opportunity to reevaluate traditional narratives of conquest and colonialism. Thus, my Penn dissertation research critically examines the anthropological phenomenon of resistance movements through a study of archaeology, material culture, ethnohistoric records, and oral histories. I focus on the events that transpired at Tunyo in 1694 (in the larger context of the revolt) as a consequence of the long-term dynamics of Pueblo-Spanish relations. An essential component of my research involves collaboration with members of the Pueblo of San Ildefonso in formulating research design, data collection, and interpretation. This engagement transcends “consultation” in that it provides a platform for pueblo members to actively participate in the archaeological process, and express their values and beliefs—perspectives traditionally undervalued by archaeologists and historians. As a result, I aim to understand how the revolt is memorialized by, and characterized in the identities of, contemporary Pueblo peoples’ social practices, lived experiences, and historical consciousness. This reevaluation of the Pueblo Revolt adds new and essential dimensions to our understanding of the dynamics of colonialism and resistance.

The Spanish in the Southwest

Prospects of a vast wealth and the fabled “Golden Cities of Cibola” motivated the first Spanish expeditions into the North American Southwest beginning in 1539 by Fray Marcos de Niza. Subsequent decades of Spanish occupation in the New Spain territory of Nuevo México (today the U.S. states of New Mexico and Arizona) were characterized by wholesale attempts to subjugate, convert, and ultimately conquer the indigenous Pueblo peoples of the region, largely by means of economic exploitation and religious persecution. Consequently, Pueblo-Spanish relations became deeply strained over time, ultimately leading to an uprising by the Pueblos against their colonial oppressors.