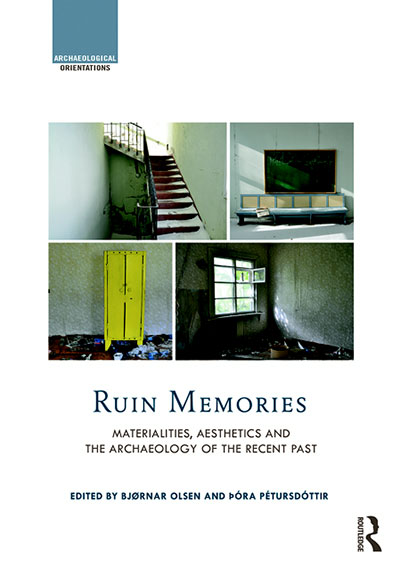

Ruin Memories: Materialities, Aesthetics, and the Archaeology of the Recent Past

By Bjørnar Olsen and Þóra Pétursdóttir, eds.

(Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2014), 496 pages, over 170 figures, $240.00 (hardcover), ISBN 978-0-415-52362-2.

It is not often that works of such divergent methodological and thematic approaches can come together with a common conviction: that things deserve to exist in their own right. This extraordinarily experimental compilation of works, although at times lacking in cohesion, is unified by its commitment to recognizing and embracing things “that may have ceased to be useful but which have not ceased to be” (p. 12). Ruin Memories is a heavy-hitter in the emergent line of works surrounding the archaeology of the contemporary past, the turn toward (or, perhaps, return to) things and materiality, and the reassessment of what is meant by the tropes of ruin, ruination, abandonment, loss, value, and modernity themselves.

The book, consisting of 24 contributions organized into 6 sections, represents a cross-disciplinary engagement with the conundrum presented by modern ruins, namely how to grapple with the ever-proliferating ruin-landscape that is a product both of the material uniqueness and mundaneness of the 20th and 21st centuries. What are we to do with industrial buildings, farmsteads, Civil War battlefields, and prisoner-of-war camps that have fallen into states of dilapidation and disuse? The introduction by the editors is eloquent and provocative, providing a much-needed framework for the diversity of works to follow. The five remaining sections attempt to think through what we, as people, owe to things; or rather, how do we ethically assess things in such a way that does not automatically reduce them to their usefulness to humans? What is the value of a ruin? And are all categories of things to be treated the same as ruined things?

The book is also rooted in the European archaeological tradition and, with some exceptions, sticks strongly to a growing canon surrounding things and materialism (Heidegger, Benjamin, Derrida, and Latour). For instance, critics might note that many indigenous philosophies have long been committed to the lives and afterlives of things in the way this volume advocates. Nonetheless, it is an aesthetically stunning and theoretically provocative book that will be regarded admiringly by anyone with a commitment to understanding how the materiality of the past tempers our contemporary lives. It is recommended for graduate students, faculty, professionals, and enthusiasts in anthropology, archaeology, historic preservation, design, sociology, urban studies, history, and perhaps even digital humanities.

Reviewed by Tiffany C. Cain, Kolb Junior Fellow and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania.