I: Contrasting Attitudes

“Modern versus the Antique

“In the Michaelmas term after leaving school, Tom Brown received a summons from the authorities and went up to matriculate at St. Ambrose’s College, Oxford. . . . He had left school in June and did not go up to reside at Oxford till the end of the following January. Seven good months: during a part of which he had indeed read for four hours or so a week with the curate of the parish, but the residue had been exclusively devoted to cricket and field sports.” (T. Hughes, Tom Brown at Oxford [London: Macmillan & Co., 1882]. 1.)

In attempting to discuss as slippery a subject as Roman athletics a number of distinctions should he established at the outset. In the first place. there are athletics and there are sports. Of the latter, which covers a multitude of transgressions, the Romans were inordinately fond, if one cares to lump under the heading such diverse pastimes as hunting, trapping, earth stopping, fowling, fishing, attending races and games mainly for purposes of gambling, observing spectacles, and amatory dalliance (cf. Webster’s New International Dictionary, 2nd. ed., “sport,” 6). Apart from the latter, only the field sports required much outlay of personal energy; the rest fall under the heading of passive “spectator activities” and will not be part of the present discussion, save as they bear on the subject as a whole. So, out go circuses, gladiatorial contests, mock naval battles, animal baitings, arena hunts, and the public execution of prisoners.

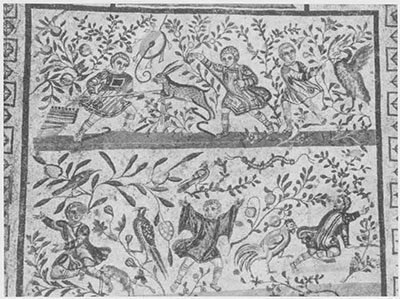

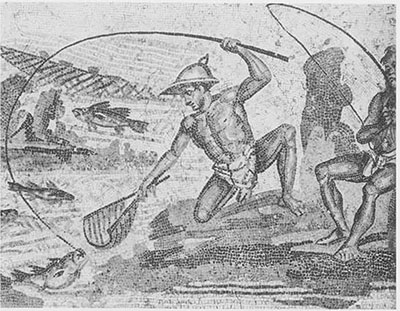

Field sports are another matter. From the evidence of the surviving literature and its reflection in the paintings and mosaics, particularly of the high empire (A.1). 70-180: see Figs. 1-2). the ancient Romans were addicted to the rustic and relatively innocent pleasures of angling, snaring, and hunting. Under the empire, what had started as private sport enjoyed in the wild was transformed into the vile arena spectacle of the urban venatio in which large numbers of animals were dispatched in a wide variety of exotic amphitheater settings. The large cats, including lions, leopards, tigers, and lynxes, were especially favored hut so were bears, bulls, rhinoceros, hippopotami, ostriches, crocodiles, elephants, and giraffes. The emperor Commodus (r. A. D. 180-1921) whose deviant obsessions with blood sports are familiar reading, personally shot in a single morning 100 lions and bears from walkways constructed for his safety above the sand of the arena.

It is in fact hard to avoid concentrating on the excesses of a few individuals when discussing the Romans, but an effort should be made to resist the temptation. There is some evidence to support the conclusion that everyday folk from many walks of life enjoyed athletic sports and games in respectable moderation. The difficulty lies in separating “observation” from “participation.” The doers tended to keep their activities within sensible limits, while the watchers were seemingly prepared to squander most of their waking hours taking in amphitheater, theater, and circus spectacles which in turn made them attractive targets for the satiric writers who provide much of our information about daily life.

The distinction that one would really like to draw between athletics and sports would be to distinguish personal participation on the one hand from collective watching on the other, but will such a separation of roles hold up? Or, to frame the question slightly differently, would Tom Brown, himself a dated and rather fustian parody of the modern world’s passion for sport, have felt at home in Rome? A key to this problem lies in the annual cycle of ludi (games) held in Rome. These were, amongst other things. formal athletic contests often deriving from religious observances that predated the foundation of the Republic. In time these came to number more than 40, and by the reign of Claudius (A.D. 41-54), the Roman calendar contained 159 days expressly designated as holidays (feriae) of which 93 were taken up with games paid for by public funds. Obviously much, if not most, of the activity generated by such an outpouring of spectacles had to be provided by professional s, as opposed to “gentlemen” amateur athletes.

“An outcrop of the religious substratum is visible on the surface of these ancient ceremonies which the Romans never omitted to perform though they had long since forgotten their significance” (J. Carcopino 1940: 206-07). On June 7 the city praetor (senior magistrate) presided over an official fishing contest that ended at the site of the Volcanal in the forum with a fish fry. According to Festus, writing in the late 2nd century A. D., the fried fish represented a sacrifice to Volcanus of fish instead of human victims. Carcopino goes on to provide an even more graphic example. Each fall on October 15 a horse race was staged in the forum. The winning horse was immediately sacrificed by the !amen (sacrificial priest) of Mars, who poured its blood over the hearth of the Regia, home of the Pontifex Maximus. Its severed head was then turned over to the inhab itants of the Subura slum district, who fought a pitched battle for the honor of who would display the “October Horse” on their walls, an atavistic practice that seems to have originated with an ancient purification ceremony to cleanse the city and protect its inhabitants with the fetish of a horse skeleton. Religious Inch with a somewhat less sinister cast included the festival of the Robigalia on April 25, which featured foot races in honor of Robigus, the god who averted mildew (sic!), and the Consualia on August 21, with its races on foot and on mule-back in honor of the ancient Italic deity Consus, who presided over secret plans and counsels.

Even gladiatorial contests possessed at the outset a kind of religious veneer, representing, as we believe they do, the survivals of Etruscan and Campanian (southern Italy around Naples) funeral games in which men were killed to provide the souls of the deceased with brave spirit companions, or perhaps to appease their craving for blood. The suggestion has even been broached that the purpose behind the early gladiatorial contests was to stir a high level of emotion amongst the living spectators to replenish the drained-off energies of the deceased. The first such spectacle was staged in Rome in 264 B.C. when three pairs of gladiators fought at the graveside of D. Brutus Pera. The pretext of their association with funerals was finally abandoned in the early empire when their purpose became largely commemorative, as well as, in practical effect, diversionary.

Another form of athletics attested for the annual festivals at an early time is boxing (pugilatio), which seems to have been imported from Greece. Livy (i, 35) says that in the inaugural celebration of the games held by the emperor Tarquinius Priscus in the 6th century, boxers were brought in from outlying provinces, and there was au old tradition that pugilism flourished in Etruria at an early date. During imperial times Caligula (A. D. 37-41) imported the best Campanian and African pugilists for the gladiatorial games, while Strabo (111. 3) records that the Lusitanians (from western Spain) and Indians also boxed. In Virgil’s description of the funeral games of Anchises (Aeneid, v, 360 ff.), the gigantic Trojan boxer Dares is challenged by the aged but huge and sinewy Elymian, Entellus, from western Sicily, thereby re-creating a scene from the contemporary arena in which the two protagonists are clearly identified as barbarian professionals.

While foot races and even races on mule-back suggest some amateur participation, the games staged in Rome’s various circuses again must have been performed largely by professional jockeys and drivers and therefore lie outside the subject of this brief article. It may be noted in passing, however, that the city’s major circus tracks were four in number: the Circus Flaminius built in 221 B.C. in the southern Campus Martius; the Circus of Gains and Nero built under the site of St. Peter’s by Caligula as a private track for chariot races; the early 4th century A.D. Circus of Maxentius erected outside the city walls north of the Via Appia: and finally the oldest and largest of the lot, the Circus :Maximus which occupied the marshy valley floor between the Aventine and Palatine Hills. While one normally thinks of these as accommodating only chariot races, we hear of circus ludi that included mock naval battles and animal hunts. In 55 B.C., for example, Pompey had to set up iron barriers around the Circus Maximus arena in order to present a battle between armed Gaetulians (from the area of present-day Morocco) and 20 elephants, who buckled the bars and terrified the spectators.

II. Mens Sana in Corpore Sano

“What have you been doing, Skinner?” “I have been up in Scotland, and getting myself in good condition for football,” Skinner replied shortly. “Ah football? Yes, I suppose we shall be playing football this term…. I shouldn’t mind football,” Euston went on, after looking round, as if unable to understand what the others were laughing at, “if it wasn’t for the dirt. Of course it is annoying to be kicked in the shins and to be squeezed horribly in the greases, but it is the dirt I most object to. If one could but get one’s flannels and jerseys properly washed it would not matter so much.” (G. A. Henty, The Dash for Khartoum or a Tale of the Nile Expedition [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, [902], 35).

If under the Republic the Romans were short on personal participation in games and sporting contests, did they eschew physical fitness altogether? For anyone with even a marginal acquaintance with the Latin authors—Caesar, amongst others, with his factual reports of forced marches, the nightly grueling construction of the camp, and bone-cracking, hand-to-hand combat—the answer is a resounding no. Moreover, it is clear that some form of amateur athletics must have taken place simultaneously with the real business at hand, which was, naturally enough from the bias of Republican Rome, training for war. Special ludi including sports that may be assumed to have stressed physical endurance, team work, and courage were part of the routine conduct of the Juventus, an ancient Italic institution for the training of young males eventually revived by Augustus. Predictably enough, the Juventus also included military drills.

That model Republican curmudgeon, Marcus Cato the Censor (234-149 B.C.), took pains to instruct his own son in “his grammer, law, and his gymnastic exercises. Nor did he only show him, too, how to throw a dart, to fight in armor, and to ride, but to box also and to endure both heat and cold, and to swim over the most rapid and rough rivers” (Plut. Vit. Cat. Mai., Clough trans., p. 251). His reaction (ibid., p. 246) to the sight of an overweight man was characteristically biting: ‘What use can the state turn a man’s body to, when all between the throat and groin is taken up by the belly?” The Campus :Martins, a low-lying area of approximately 600 acres between Rome’s Capitoline, Quirinal, and Pincian hills and the Tibur River, is connected by use as well as name with military activity, since we know that the Republican citizenry used its grounds to assemble for army functions. Appropriately enough, it also served for-athletic exercises for Roman youth, although just how vigorously their exertions were pursued is cast in some doubt by Strabo’s statement (5, 236) that the Campus Martins contained “a multitude of people exercising with ball and hoop.”

Possibly in reaction to the growing addiction of Romans of all classes to circus ludi and amphitheater munera (gladiatorial shows), a number of prominent Republican figures attempted to introduce Greek style athletic games to Rome. The earliest of these were staged in 186 B.C. by Marcus Fulvius Nobilior, who imported large numbers of Greeks to perform in Rome. A century later the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla managed to clean out nearly all of Greece to provide athletes to help celebrate in Horne his victory over Mithridates, which meant that in 81 B.C. the best that Olympia could put on for its games was the foot race. Similar efforts were repeated by Pompey, Julius Caesar and Augustus.

Both Caligula and Claudius staged gymnastic competitions for the Roman people, using foreign athletes, limit it was Nero who provided Greek sports with their must sincere and enthusiastic support. Nero saw to the establishment in A.D. 59 of the fucenalia or “Youth Games,” in which nobles were again encouraged to compete with the lower classes in a variety of athletic events and recitations of poetry and song. Two years Later he added the Neronia, to be staged every four years after the model of the Greek games. He had a Greek style gymnasium complex constructed in A.D. 62, either as part of his baths or somewhere nearby in the vicinity of the Pantheon, that was the first such structure to he erected in Rome.

That the reaction of Nero’s more conservative contemporaries to these games was not entirely positive may he gauged by Tacitus’s description of the crowds attracted to the Juvenalia: “Birth age, official career did not prevent people from acting in Greek or Latin style—or from accompanying their performances with effeminate gestures and songs. Eminent women, too rehearsed indecent parts. . . Places of assignation and taverns were built, and every stimulus to vice was displayed for sale. . . Promiscuity and degradation throve. Roman morals had long become impure, hut never was there so favorable an environment for debauchery as among this filthy crowd” (Ann. pp. 310-11, M. Grant trans.). Perhaps the insinuations of sexual misconduct arose in large measure from merely the sight of athletes competing naked in front of both sexes, but we do hear of one Palfitrius Sura, son of a consul, wrestling naked with a girl from Sparta.

Apart from music, Nero’s greatest passion was for horses, riding as well as driving them, an interest that evidently stemmed from his childhood. During his reign he defended his unprecedented (for an emperor) obsession with chariot racing as being kingly, ancient, and sanctified by religion and the ancient poets. When a misguided official tried to suppress the rough behavior of some of the circus drivers by substituting dog for horse races, Nero intervened on behalf of the drivers. In A. D. 59 he personally drove a team of horses in the Vatican circus before a private audience. Soon after, despite Senatorial disapproval, the public was admitted to repeat performances. In later years the emperor’s hair was crimped in steps like a charioteer’s. Much of his final two years was devoted to chariot racing in Greece. He fell during the Olympic games and could not finish the course, but the judges prudently pronounced him the winner anyhow and pocketed a large subsidy. Back in Rome he hung his trophies in his bedroom and eventually gave a public exhibition of all 1,808!

After Nero’s death the games faded away until Domitian replaced them in A.D. 86 with the Agones Capitolines set in his Circus Agonalis, on the site of the present-day Piazza Navona, which was capable of holding some thirty thousand spectators. Like the Neronia, these games were celebrated every four years, probably in order to facilitate the participation of the foreign contingent, for the bulk of the competitors were by this time largely recruited from among Greeks and the populations of the Hellenized east. E. N. Gardiner cites the career of one Titus Flavius Artemidorus of Adana in Cilicia, who won the pankration in the first Capitoline Games in A. D. 86, as well as the four major Panhellenic Games in Greece and in numerous other imperial centers.

Prizes were awarded personally by Domitian, who presided over the contests wearing a Greek purple mantle and Greek shoes; on his head he bore a golden crown with images of the Capitoline Triad deities, Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. The events themselves were an odd mixture of traditional Greek style athletics and artistic performance, with prizes given out for foot races and eloquence, boxing and Latin poetry, discus-throwing and Greek poetry, javelin casting and music.

While these games survived Domitian’s death and, with the support of such emperors as Hadrian (A.D. 117-138) and Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161), lasted down to the 4th century, their appeal (and that of the various other games periodically introduced by some of the later emperors) was narrowly limited to the intelligensia. They never gained the wide popularity of the circus and amphitheater. Even the upper classes disliked the games, ostensibly because of the nakedness of their participants, but more likely because they found them a bore. Despite this fact, or perhaps even because of it, the foreign athletes were granted special privileges in Rome and the right to form their own guilds called synods. The Synod of Heracles, for example, was transferred from Sardis to Home. perhaps during the reign of Hadrian, where it was provided with its own gymnasium on the Esquiline. The facility was used for displaying honorary statues and storing athletic diplomas as well as for training its members, Its official cult combined the worship of Heracles with that of the imperial patrons of the games: the reigning emperor was represented as Hermes Agonios, god of the palestra and lord of contests.

III. Sports Fever

So Tom gave himself up to the contemplation of the rooms in which his fortunate acquaintance dwelt. . . . There was a queer assortment of well-framed paintings and engravings on the walls. . . . Phosphorus winning the Derby: the Death of Grimaldi the famous steeple-chase horse—not poor Joet an American Trotting Match, and Jem Belcher and Deaf Burke in attitudes of self-defense. Several tandem and riding whips, mounted in heavy silver, and a double-barreled gun and fishing rods occupied one corner, and it polished copper cask holding about five gallons of mild ale, stood in another. In short there was plenty of everything except books.” Tom Brown ill Oxford. 23-24.

The evidence developed thus far for a specifically Roman interest in personal athletics is altogether sparse. but what there is suggests that its principal appeal lay. at least during the Republican period, in developing military skills and fostering a patriotic esprit. Accurate as far as it goes, this reconstruction would he incomplete without a word about the thermac or baths, which, during the empire, provided For Romans of all ages what the 19th century British public. schools and universities gave their cloistered youth—a haven and an excuse for a virtually unlimited indulgence in exercise and athletics. These establishments. built for public use on increasingly greater scales of lavishness and size, numbered in the capital city as many as 170 by 33 B.C. when Agrippa took a census of the number. A century later Pliny the Elder found them too numerous to count, although it has been estimated that something approaching a thousand thermae existed in Rome alone before its decay in later antiquity.

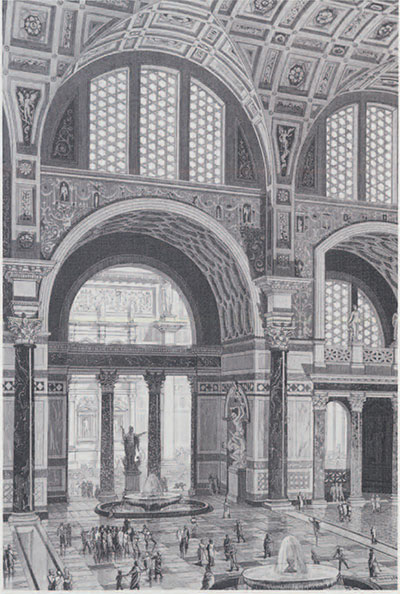

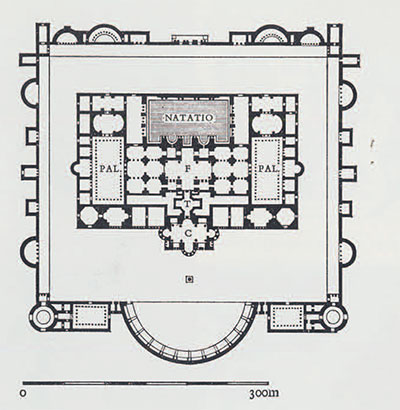

The big imperially sponsored baths such as those of Titus, Nero, Caracalla (Fig. 4) and Diocletian (Fig. 5) have been called “thermal cities” because of their sprawling size and extraordinary range of facilities. Apart from every type of bathing installation imaginable (short of jacuzzis), they inducted libraries, sitting rooms, art galleries, formal gardens, covered walks, and what is of present interest, palaestrae or exercise facilities surrounded by terraced porticoes. Diocletian’s immense bath building northeast of the Vintinal hill covered an area of some 13 hectare (more than thirty-two acres). The late John Ward-Perkins has described it as representing the urban bath type at its grandest of maturity. The plan (Fig. 5) shows the position of its two symmetrically balanced palestras, backed by recreation rooms and flanking the central bathing complex and outdoor swimming pool (natatio). It is Carcopino’s thesis that the real originality of bathing establishments like Diocletian’s lay in providing a union between the world of physical culture and intellectual pursuit, and that this in turn helped to soften the Romans inveterate dislike of exercise for its own sake. Within the privacy of the baths both men and women could join in Greek style sports then steam, have a massage, and bathe in the nearby bathing rooms (Iaconium, caldarian, tepidarium, and frigidarium), and finally repair, if they so wished, to the libraries and art galleries for a bit of intellectual nourishment without ever leaving the confines of the baths.

Our sources describe a number of palestra games using balls. The harpastum, for example, was a kind of medicine ball stuffed with sand or hair. The object was to grab it away from your opponent and then run, sprinting and feinting and kicking up dust. The game, which sounds a good deal like rugby, was said to be especially exhausting. The pila pagancia was just the opposite sort of ball, very light and stuffed with Feathers—a kind of Nerf ball (modern foam-filled ball)? The follis was inflated with air and bounced off the ground like a basketball. The game of trigon also involved a ball.

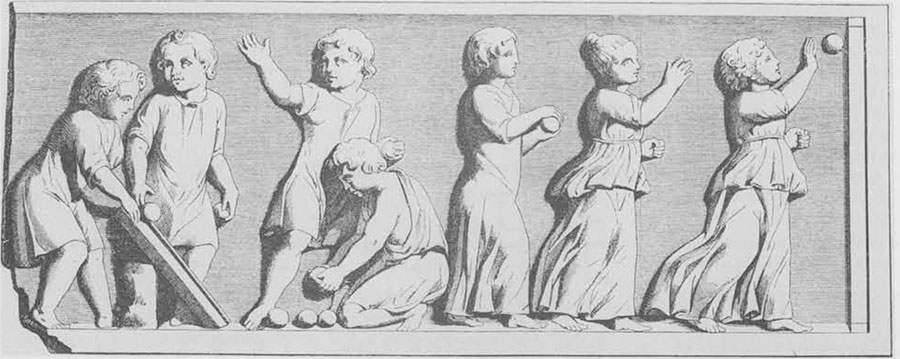

Galen, who wrote in the 2nd century A.D., says in his treatise on “Exercise with the Small Ball” that ball playing is beneficial to persons of all ages because the action can be varied from gentle to strenuous. Examples of the former can be seen in a relief from Roman Campania that depicts boys and girls bouncing balls off a wall (Fig. 7) mid rolling balls down an inclined plank apparently with the object of hitting three balls lined up on the ground; the latter game seems to combine features of playing marbles with bocce. A 3rd century A.D. sarcophagus (Figs. 8. 9) in the Lateran Museum in Rome depicts, on the left, cupids rolling hoops with sticks. In the center children ride piggy-back (chicken fight?) and play with nuts or marbles, while to the right they hurl balls with throwing sticks (Roman jai-alai?). None of these children’s games, however, necessarily took place inside the thermal palestras.

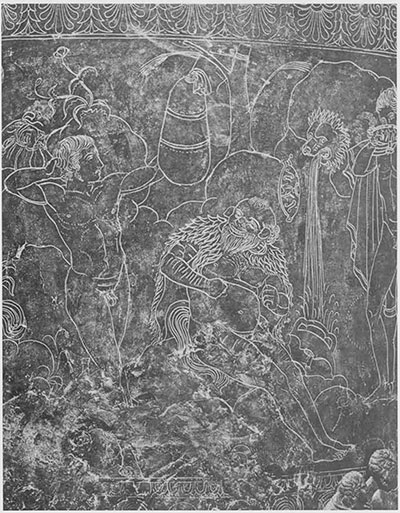

A different sort of palestra exercise, borrowed from the training program for army recruits and gladiators, involved shadow-fencing with a rapier either against a pole (ad palum) or a dummy. Martial mentions a woman engaging in this particular form of exercise. Yet another form of exercise made use of a ball called the corycus, which was filled with either earth or flour and then pummeled. The Greek version of this may be what is represented on the familiar mid-4th century B.C. bronze Ficoroni cista (cylindrical covered box) From Praeneste that depicts one of the Argonauts punching a stitched hag hanging from a tree, to the evident amusement of his silene companion (Fig. 10). Running. running and rolling a hoop (trochus) at the same time, and working out with dumb-bells (halteres) were also favorite games of girls and women as well as boys and men. Martial expresses the conservative point of view when he asks, Why waste the strength of the arms on stupid dumb-bells when it would be better exercise for young men to dig in a vineyard? The behavior of the emperor Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 161-180) reflects what seems at least to a modern audience a more enlightened attitude. He was a regular visitor to the palestra, arriving in the late summer afternoon or close to sunset in the winter to box, run, and wrestle.

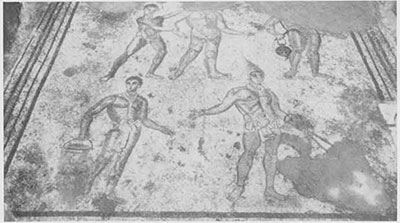

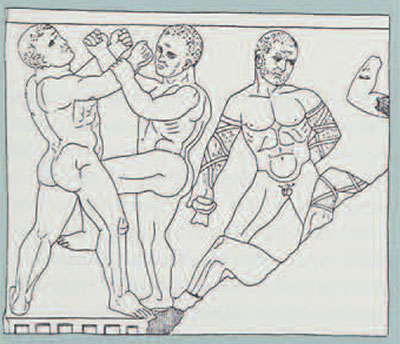

Even women participated in wrestling, although it was more normally a male activity. At a banquet given by Apicius, who lived (luring the early empire. one lsidorus. a vigorous old gentleman of 91 years. extols his skills at wrestling as a method of prolonging life. The actual match was preceded by first smearing an oil unguent over the muscles to loosen them up. A coating of dust was then patted over the body to provide one’s opponent with a proper grip. A small square room, known as the chamber of the unctiones or massagers, excavated in the late Roman villa at Piazza Armerina in Sicily, was set between the frigidarium and tepidarium of the villa’s baths, and seems to have been used for anointing athletes. Its floor mosaic (Fig. II) depicts five male figures. The top central male is a stockily muscled, naked athlete being massaged by a young servant. A second servant to his right holds an oil flask and a strigil for scraping the skin. Two other large athletes occupy the lower ground, wearing loin cloths marked with their names, Titus and Cassius, in the vocative case. The figure to the left holds a brush and bucket (for applying the dust?). The figure on the right (Fig. 12) wears a tall conical hat which may represent a victory trophy. While some scholars describe the large figures as boxers, none wear the caestus or loaded boxing glove, and they are better interpreted as wrestlers. Despite their Roman sounding names, to Roman eyes these figures would have had the brutal appearance and overdeveloped bodies of proletarian, non-Italic foreigners and are therefore surely professional performers as opposed to amateur athletes.

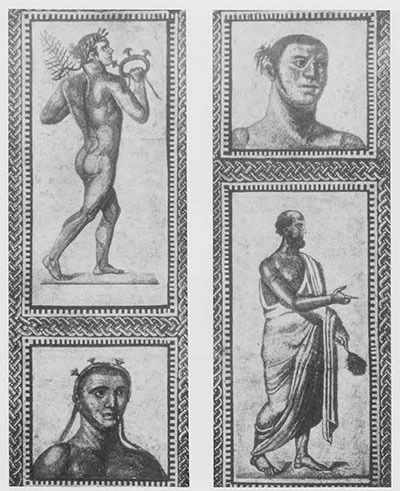

This brings us at last to the famous floor mosaics (Figs. 13-15) in the Vatican Museum, found in 1824 in a semicircular exedra (recess with raised seats) of the Baths of Cara-calla. Their date is probably the 3rd century A. D. These mosaics portray, in individual paneled settings, victorious athletes and gymnasium officials. Of the recognizable types there are a boxer wearing the caestus, a javelin thrower, a discus thrower, and what is probably it wrestler. Each is placed on a low mat-like plinth that suggests that they may represent statues rather than actual victors. Smaller squared panels depict busts of additional athletes and victory crowns, decorated with raised images of deities, which recall Domitian’s crown with the images of the Capitoline Triad and further suggest that the victories here may have been achieved in the Agones Capitolines. Incidentally the mosaic crowns are roughly similar to the crown worn by the 4th century marble head of a priest from Turkish Caesarea (Kayseri) in The University Museum’s Roman gallery. Despite their bathing establishment provenience these brutal depictions of heavily developed men with slightly moronic expressions, closely cropped hair, and projecting top-knots of hair (cirri in certice) must portray professionals who made their living in the imperially sponsored games rather than amateurs, who would in any case never have boxed with spiked, “limb-piercing” caesium’s.

As so often is the case, it seems that the professional athlete was far more frequently of public interest than the amateur.

As an example of the difficulties of documenting amateur athletics in the Roman world by archaeolgoical evidence, Professor Roger Edwards (former Keeper of the Mediterranean collections in the Penn Museum), after scouring the collections for some sporting relic, could produce only two metal objects. The two objects have been described variously as bow-pullers, spear-throwers , lampwick holders, screwdrivers, chain shorteners, horse curbs, harness attachments, and myrmekes (the metal spikes strapped to the leather caestus, or gauntlets, with which Roman pugilists wrapped their hands).

Alas, W.B. McDaniel, a former curator in the Penn Museum, wrote an article that convincingly demolished these attractive theories; he argued instead that these objects may have served as magical amulets attached to race horses (McDaniel 1918). Whether “Knuckle-dusters” or amulets, their association is once again within with the world of professional sport, and therefore, while most characteristically Roman, they seemingly tell us nothing about the more elusive world of private, personal athletics.