Beauty may well be in the eye of the beholder but for thousands of years many persons have felt it appropriate to combat this philosophical thought by employing various techniques of deception, or perhaps we should say enhancement. As a result there has developed from time to time in the history of the world’s civilizations a lucrative trade in cosmetics. One of the most flourishing periods for this form of business investment was that of the Roman Empire and one of the finest of all Roman cosmeticians was Cosmus, a man unrivalled both in skill and in the scale of his prices.

This small perfumer with the flowery name has been dead about eighteen hundred and fifty years; the remains of his shop rest unidentified beneath the crowded streets and apartments of modern-day Rome. But in the opulent days of the emperor Domitian, some five or ten years after the sudden destruction of Pompeii in the summer of A.D. 79, the name Cosmus was very much alive on the beautiful lips of feminine society.

In those years of luxury the noble ladies of Rome found themselves delightfully trapped in a whirl of high fashion. Yet the most expensive dresses of fine wool or gold-embroidered purple linen meant little if physical beauty and alluring charm were not also present to intrigue the stronger sex. To implement this feminine desire for conquest there existed in the teeming capital of the Roman world certain neighborhoods where specialists in beauty aids vended their wares. During morning business hours slaves of Syrian or Greek extraction slipped quietly out of the great Roman mansions on the Aventine, Esquiline, or Quirinal hills and hastened through winding streets and alleys toward the congestion of noises, filth, and stores called the Subura, nestling in the valley just north of the main Roman Forum. Indeed, this slum district was so objectionable that the emperor Augustus earlier had built a wall to shut it off from his magnificent marble temple honoring Mars the Avenger.

Yet here in this mass of vile language and equally vile manner of living were to be found the counters across which women of fashion purchased their temporary beauty. Of course, they had to send slaves for these precious acquisitions; the Subura was a haunt for prostitutes and no fastidious lady could chance being confused with these cheaper rivals for the attention of men. And so it was the servile confidante who trotted back from each shopping trip laden with creams and perfumes sealed in delicate jars of alabaster and misty-thin glass.

Then, too, there were other purchases of a rather secret nature; the lustrous hair admired by all at the dinner table may have arrived only that very day from some little shop near the temple of Hercules and the Muses in the shadow of the Circus Flaminius. And in far-off Germany a newly-shorn Sygambrian girl wondered how well her tresses looked on the head of a cultured Roman matron, bald as a bird’s egg.

And what of the gently ladies whose teeth, blackened and aching, had been seized by the pliers of the brutal dentist Cascellius and wrenched from their customary sockets? Aegle, a Roman lady once popular in her particular circle, knew exactly what to do. She bought a set of bone and ivory false teeth and gave up her broad healthy smile. Both Laelia and Galla, rivals in the endless social charm contest, decked themselves out with false teeth and wigs as well. And Galla even glued false eyebrows to the embarrassed ridges above her eyes. Old Ligeia could not stand the thought of a wig so she exposed all three hairs of her head to public view–a brave lady, indeed. We know of these rare Roman beauties through the satiric writings of men like Martial who stripped all deceit from the ladies of their acquaintance and published the poetic revelations in scrolls for anyone to purchase.

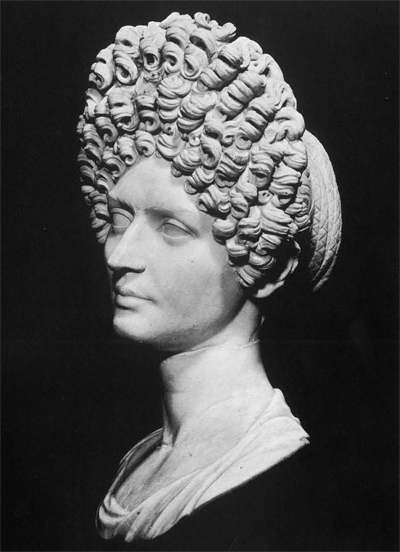

typical of those used by Roman women of the Imperial period.

The threadbare satirists were also charmed and amused by the intricate hair styles with tiers of flat, tight curls rising vertically from the powdered foreheads of their lady-friends. Every Roman woman of wealth kept on her household staff a serving girl experienced in the arrangement of such coiffures. Lalage, a tempestuous damosel of Marital’s acquaintance, had such a prize in Plecusa. But one day a pin dropped from Lalage’s hair and without hesitation an unrestrained curl sprang to embarrassing prominence. Swinging like a professional gladiator, the elegant lady seized the pin and punctured Plecusa’s arm–a rather vicious way of serving a reprimand. Worse was in store for the poor girl who singes her lady’s curls.

But it was not enough for these domestics to be versed in techniques of curling and waving hair. They also had to be familiar with the action of hair dies. Many idle Roman women alleviated the tedium of their days by varying their hair color according to whim. Others, of course, postponed the appearance of age by the same practice if unsightly grey hairs proved too numerous to be plucked, for dyeing, Batavian foam was a good choice–one of the best formulas available for turning the hair blonde. Or there were dyes from Mattium, also in Germany, for those who preferred to become provocative redheads.

Beyond a doubt there were other matters of beauty which concerned self-respecting ladies of station–such as those ugly wrinkles or peculiar skin blemishes. In the case of warts one always recommended nitre; halcyon cream, a distasteful mixture of honey and cleanings from birds’ nests, could always be counted on to banish freckles. Proud Lycoris envied the light complexion of her friends and desperately sought to conceal her darker skin under layers of powdered white lead. Another lady, Sabella, followed her example while the elderly Fabulla plastered the dust of pulverized pearls over her features to accomplish the same effect. On the other hand Polla, who was extremely worried about her aging and wrinkled skin, turned to an old housewives’ recipe: she encased herself in a thick layer of bean meal and awaited the magical disappearance of proofs of her advancing years.

These are scattered details, however, which might best be understood if we imagine the step-by-step concerns of a typical Roman patrician at her toilette. First she would probably pluck her eyebrows with small bronze tweezers. A salve of soot and oil of sesame was applied to soothe the irritated brows and to prevent regrowth of the hairs. Then there were depilatories for use on the arms and legs; the best of these was a malodorous combination of resin and unmentionable ingredients. When this had been wiped off it was appropriate to rub the hands with pumice to smooth the skin. Next came the bath which women of the poorer classes could only take during the morning hours in one of the many public bath establishments throughout the city. The aristocratic lady had her own cold, tepid, and hot bathing rooms at home, nicely equipped with round marble wash basin, sunken tub ornamented with mosaic work, and walls covered with delicate designs.

A woman endowed with truly expensive tastes and an adequate income might choose to fill her tub with warm, frothing asses’ milk, a liquid certain to ward off wrinkles and skin discolorations. This particular discovery was made by that flamboyant and obstreporous wife of the emperor Nero, Poppaea Sabina. Unfortunately for her she scolded Nero one day for coming home late from the races; he kicked her in a fit of temper and, being pregnant at the time, Poppaea succumbed to the injuries. She died probably in her late thirties, never actually having proven the efficacy of the asses’ milk.

Once in the tub, whatever its contents might be, the bather evidently used a powdered soda for cleansing purposes, then stepped out to be dried with a large sheet of linen or wool. The soda having dried the skin it was now necessary to anoint the body with quantities of oil; berries grown at Venafrum in Campania produced a sweet-smelling unguent in great demand. After this, one came to the choice of a special cream to stimulate the facial tissue. Pliny the Elder tells of such a cream composed of incense and nitre mixed with gum stripped of its bark, a cube of juicy myrrh, fennel, dry rose leaves, frankincense, and Libyan salt. These ingredients were pulverized to a powder with mortar and pestle, then moistened with honey and mixed into a cream with barley juice. Men like Cosmus made regular excursions to purchase these items from the importers’ warehouses at the Emporium along the Tiber banks below the Aventine or in the Horrea Piperataria, a warehouse covering ruins of Nero’s Golden House on the Sacra Via.

Having taken full advantage of this special face cream the lady would wash it off and turn to the cleaning of her teeth. This involved the use of powdered deer’s horn which might be kept in a small glass bottle. It was rubbed over the teeth or gums with a small fibrous stalk, bruised so that one end splayed out like stubby bristles in a brush.

The use of another face cream might not be out of order, but this time it would be sweetly perfumed swan’s grease, excellent for softening wrinkles and cleansing the pores. While this was being absorbed into the skin a serving girl could begin with the arrangement of her mistress’ hair. From another glass container great drops of Mendesian unguent were scattered over the hair. This particular preparation was an Egyptian import and consisted of oil of bitter almonds, oil of unripe olives, cardamon oil, honey, wine, myrrh, balsam, and a little resin to make the aroma more permanent. An ivory comb could be used to work the substance into the hair. Meanwhile a curling iron would be heating close at hand in a low bronze charcoal brazier. With this instrument and a variety of ivory and gold pins, the curls would be twisted, greased, and secured in position. Waves would be patterned along the sides of the head and the extra hair at the back would be braided and pinned in a bun or led forward over the crown of the head. With this operation completed the great lady would wash off the swan’s grease, pat her face dry, then dust her face, neck, and arms with powder applied with a pad of folded linen or wool. Then, dipping her fingers into a small delicate box filled with pulverized poppy leaves, she would brush a light pink onto her cheeks and perhaps a bit on her ears.

Eyebrows and eyelashes certainly could not be overlooked and the Roman cosmetician offered many things for their enhancement. Saffron powder mixed with oil was easily brushed on with a slender bronze or ivory rod. Also available were the ashes of burned goat flesh or even antimony, an age-old beauty paint. For the lips one invariably used wine lees as a stain.

To add a finishing touch to the face, it was not unusual to attach a tiny patch of black cloth to one cheek; this might be patterned as a miniature crescent moon. And behind the ears as well as in other strategic spots one always dabbed on an assortment of exquisite perfumes, many of which came from Egypt, Arabia, or Syria. With sweet-smelling odors in the air it was always well to remember the need for masking bad breath; for this one used a liquid flavored with myrrh or even laurel leaves which could be carried with one and chewed at any time.

Indeed, the toilette of a Poppaea, a Domitia, or a Lalage was not a simple affair to be dismissed lightly by modern practitioners of this delicate art of deception. Laelia’s mosaic-floored bathing rooms are chipped and pressed in darkness below the earthen accumulation of centuries–her perfume jars, water basins, hair pins, and ivory eye paint sticks are scattered through museums of the world. Cosmus’ shop is closed and buried in oblivion’s wreckage, his formulas known only through antiquarian reports.

But surely there is the chance that one day someone may say “Here is where Laelia lies buried” or “There is the jar for the ashes of Cosmus.” Rest assured, whenever you approach a cosmetics counter you will hear the clerk speaking to you in the spirit of Cosmus himself. And in every lady’s boudoir there still lingers the lovely shadow of some Roman beauty.