Archaeology consists of both reconstructing what happened and explaining it happened. archaeological has always been conducted with an eye towards reconstructing the and most studies still emphasize, the linkages between human behavior ,orb and material residues. Other stories have been inspired more by dill II-ties in explaining the whys, and I’ve explored the causes behind mu. ..A phenomena that must have occurred in the past.

My research on a group of fair, as in Nigeria is an example of the law ; I went to Africa to study I why farmers’ strategies shaped then-folding of a settlement pattern. I w those settlements might be determined and interpreted in years hence is of secondary concern. In fact, the questions that led to this process, it crystallized while doing archaeology in an area where the problems if detection and interpretation were radically different.

A Southwestern Beginning to an Africa Study

When I first saw it, site D:2005 was a scatter of rock and potty y around a shallow depression. It but I been built, exactly 1,117 years before, as a farmstead for a small group of Anasazi Indians, part of a sparse population that had hunted and farmed on Black Mesa in what is now northern Arizona. D:2025 was an unimposing site comprising a pet-house, a waddle-and-daub summer hut, a few storage structures, and a sparse scatter of refuse that suggested a fairly short stay. But it was while I excavated this site for the Black Mesa Archaeological Project t that I was led to a theoretical question in archaeology that would evenntually take me to the savannas of central Nigeria, where another group of farmers were building and abandoning farmsteads.

This article is about those Nigerian farmers, but the motivation for going to Nigeria in the first place came from a problem in archaeology: our lack of understanding of farm settlements. Settlement patterns have been a focus of study by archaeologists for decades, and there has been exciting progress in our understanding of hunter-gatherer settlements and how those settlements relate to hunting and gathering strategies (for example, Binford 1980). Meanwhile, research on agrarian settlement—those farmsteads, hamlets, and villages that dominate much of the archaeological record—has lagged behind. When a series of questions arose concerning early Anasazi farmers on Black Mesa, there was no particularly useful body of theory to which I could turn.

Some of the questions were both interesting and important. A few hundred meters up the slope from D:2025 was another small site, D:2023. It was a similar farmstead, with pottery dating to the same period. A few hundred meters down-slope was D:2027, a third site from the same period. It was somewhat larger, but still a farmstead. All three sites were excavated in the summer of 1982.

Several of us were interested in the relationship among the three sites. They were probably either contemporaneous or sequential: either three farmsteads grouped fairly closely on a sparsely populated mesa, or the remains of one family’s moves. Until treering dates were available, these questions couldn’t be answered empirically. Therefore my thoughts turned to theoretical approaches: what factors should affect the locations, spacing, and abandonment rates of such settlements? There must have been many variables that played a role in these farmers’ decisions on farming and settlement; was there any way to separate those that would have been overriding from those that would have been overridden?

The Idealized Plain

Geographers have dealt with this type of problem before, and they have worked out a solution: imagine a situation untainted by the quirks of history, landscape, or human behavior—an idealized, uniform and ahistoric plain, populated by totally rational and knowledgeable people. This provides a mental laboratory for isolating the basic dynamics of settlement and the relationship between settlement patterns and the activities of the people in settlements.

This is what J.H. von Thünen did in the early 19th century. Concerned with the underlying principles of land use, he reasoned that, when other factors are held constant, the farmers in a town will maximize profit by planning land use according to the costs of transporting crops to town. Since transport cost is largely a function of distance, land-use patterns should be explained by the distance between town and a given plot. This explained the concentric rings of land use that occur not only around towns but, as the geographers later showed, around individual farmsteads as well (Chisholm 1979). Knowing what factors govern land use on an idealized surface provides a basis for understanding real situations, where variables aren’t so controlled. Figure 2 shows the classic model of concentric land use.

Walter Christaller used the same approach to isolate the logic underlying the arrangement of market towns. He demonstrated that, on an idealized surface, geometric hierarchies should develop in response to the rate at which people availed themselves of stores, services, and other “central functions.” The result was Central Place Theory, which offers key insights into market settlement patterns.

Both Central Place Theory and von Thunen’s land-use theory have been useful to archaeologists, but they shed no light on agrarian settlements such as those on Black Mesa. What I really needed was not a model of the relationship between a single town and its farming, or of the relationship between a market town and the marketing its people do, Abut of the relationship between small farming settlements and the farming done. Could we not imagine a small population of rational farmers on a uniform plain? Is there any way to predict how they will settle, and how their settlement pattern will change through time?

Attempts at modeling this process have not been especially successful. The model usually used by archaeologists interested in the problem, borrowed also from a geographer (Hudson 1989), envisions settlement evolving through three stages. In the first, farms are located randomly, like plants. In the second, clusters of farms might be formed by fissioning; this follows the conventional assumption that daughter settlements would stay as close to the parent as possible. Or, new immigrants would avoid existing farms, producing unclustered settlements. Finally, competition over land would force the smaller farms to sell out to the larger ones, leaving widely spaced farms.

From this model, which has been used widely in archaeology, and other archaeological attempts to capture the dynamics of farm settlements, one could assemble a set of notions about how farms should theoretically behave. Initial settlements should be randomly located. When settlements fission, the “offspring” should be as close to the parent as the cultivated perimeter allows. Immigrants should settle away from extant settlements. Curiously, Hudson and others dealt with rising rural population yet assumed no change in agricultural intensity (see box on Intensive Farming).

How should farmsteads, in theory, behave? I concluded that we needed a set of baseline expectations for agrarian settlement, such as those provided for market towns by Chris-taller and for land-use patterns by von Thünen and Chisholm. That summer at Black Mesa, we talked about how fascinating it would be to monitor the evolution of a real agrarian settlement system, beginning at a “zero point” with a small initial pioneering population.

The Kofyar

It was perhaps coincidence that I had also been working with Robert Netting, a cultural anthropologist whose work on agrarian ecology has inspired many archaeologists. I was helping him reanalyze the remarkable data he had collected on the Kofyar, a group of farmers in the Jos Plateau of Nigeria. When Netting had studied the Kofyar in the 1980s, he had concentrated on their homeland, where a relatively crowded population practiced highly intensive agriculture (see box). But the Kofyar were also establishing farms in a frontier area a day’s walk to the south, where they could capitalize on the abundant farmland by reverting to extensive cultivation. They were also marketing agricultural surpluses for the first time.

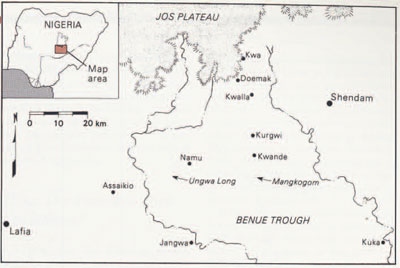

The more I thought about the Kofyar, the more their frontier seemed to offer a unique opportunity to try to seek the sort of underlying logic of settlement on a real plain that von Thunen and Christaller had isolated on imaginary ones. Although there are no ahistoric or uniform plains in real life (any more than there are perfectly rational or knowledgeable people), the savanna south of the Jos Plateau allowed control over an unusual number of variables. For instance the area offered vast expanse of good farmland, long empty be set of the threat of slaving and rag (Stone 1988). It was not a settlement system beginning at a “zero point ,” but it was close.

Agricultural potential was not uniform, but the main variation as among three broad, readily identifiable zones with soils from different parent materials. This would comparisons of the effect of soil on settlement decisions. To provide some perspective on how “perfectly rational” were Kofyar’s actions, there was another per group also colonizing the same savanna—the Tiv, whose traditional system of extensive agriculture I provided¬ a perfect contrast to the intensive-farming Kofyar.

What, then, was my goal in turning to ethnoarchaeology? In contrast to many ethnoarchaeological studies. it was not to compare Kofyar activites with the remains they left behend (although by the time I left Niger I had learned a lot about that). It was as to reconstruct the evolution of this settlement system, and to explore how settlement change related to what the Kofyar were doing in those settlements-farming. The Kofyar were certainly no analog for the Anasazi, and I had no illusions about them revealing “the” processes by which agrarian settlement operated; I was convinced then (and now) that we have to think in terms of multiple trajectories that such systems might follow. But it seemed to me that, considering the difficulty archaeologists had modeling agrarian settlements on a hypothetical plain, the best thing to do was to try reconstructing agrarian settlement evolution on a real plain, to see how farmers sifted through the many factors to make their decisions.

Piecing Together a Settlement System

Namu is a small town 30 kilometers south of the Jos Plateau of Nigeria (Fig. 3). It is on the northern edge of the Benue Trough, where there is a vast savanna that, until a few decades ago, contained large areas of good farmland with very low population. The low population, concentrated in walled settlements like Namu, Kwande, and Kurgwi, was due to the threats of raiding and slaving by emirates such as Labia and Waste. The Kofyar and other groups sought refuge in the rocky hills of the Jos Plateau, where they endured high population densities and the hard work of intensive agriculture.

The Kofyar began to farm the fertile Benue lands in the early 1950s, first migrating down seasonally and later moving permanently. On the frontier they grew the same grains they had in the homeland: sorghum for food and millet for beer. They also began to cultivate yams and rice as cash crops. They mostly lived in single-household compounds, 6 to 10 mud huts plus activity areas, that I call “settlements” (Fig. 1).

By 1960, when Netting first came to the Jos Plateau, around a quarter of the Kofyar population was involved in farming on the Benue frontier. Then and in 196B-67, Netting collected information on the frontier area that provided an invaluable baseline for my research on the settle ment system. I did my fieldwork between January 1984 and March 1985, collaborating with Priscilla Stone (who was studying Kofyar women’s economic strategies) and Netting. While the three of us investigated the Kofyar agricultural system, I also explored the issue of settlement evolution through several lines of evidence (Stone 1988).

I had brought Netting’s earlier information to the field in the form of computer printouts that allowed us to track down several hundred previously recorded households. We also censused over 800 households on the frontier, and for each we reconstructed a household settlement history. When computerized later, these settlement histories provided an indispensable source of information on how settlements “behave,” and how household settlement decisions are linked to agriculture and domestic cycles.

I also acquired aerial photographs of the frontier for different points in time (1963, 1972, and 1978). These photographs were a gold mine. With my Kofyar assistant, I spent hundreds of hours walking down dirt paths and across sorghum and yam fields, carrying aerial photos, a Brun ton compass, a distance measuring wheel, and computer printouts. I eventually identified close to 800 settlements on the aerials, recorded locations of new compounds, and investigated the compounds that had been abandoned since the photographs were taken.

Back at the University of Arizona, I developed a database system that allowed me simultaneous access to this spatial data and to the censuses with their settlement histories. This has allowed me to reconstruct many aspects of the evolution of Kofyar settlement. I will briefly describe a few of the lessons to be learned from this reconstruction.

Are Pioneer Settlements Random?

One of my first topics of investigation was how settlement locations were determined on the frontier, and if we should expect these determinants to occur at the beginning of other settlement trajectories. It turned out that pioneer settlements were not located randomly, which probably should surprise no one.

For example, 19th century pioneers in northern Argentina tried to settle in strips rather than in the government-favored pattern of each farmstead on a 25 hectare square of land; one of the reasons was agricultural labor mobilization (Eidt 1977).

How can farmsteads be closely spaced without being reduced to small plots? Simple: farms are elongated, with residences near the center. This turns out to be a common solution, occurring in both Argentina and Nigeria, as well as in Germany, where the pattern is called Waldhuf en (Mayhew 1973).

Paths and dirt roads “attracted” compounds because of all the foot and bicycle (and even motorcycle) traffic, and because they allowed the lorries and pickup trucks of crop traders to drive close to the yam fields after the harvest. The attraction of compounds to each other and to roads produced strong patterning in settlement spacing: 82 percent of all compounds are located between 100 and 200 meters from their nearest neighbor. Compounds were never isolated unless they housed an unusually large group, and even then there would be attempts to recruit other farmers to the locale.

The archaeological wisdom that interaction controls site spacing was partly right. But it is clear that there was a particular kind of interaction—collaboration in food production—that was critical in shaping this arrangement of farmsteads. The conventional wisdom that a settlement’s cultivated perimeter determines settlement spacing is somewhat misleading. We may be fooling ourselves in assuming that farmsteads or hamlets use circular perimeters, as plot shape is easily altered to allow sites to adjust their spacing.

How Do Farmers Pick Locations?

Saying that the farming system pulls farmsteads towards each other doesn’t tell us where the settlements end up. Analysis of site location has been a mainstay of research in archaeology, although general rules of location have been slow to materialize. How the Kofyar criteria for site selection changed through time was intriguing.

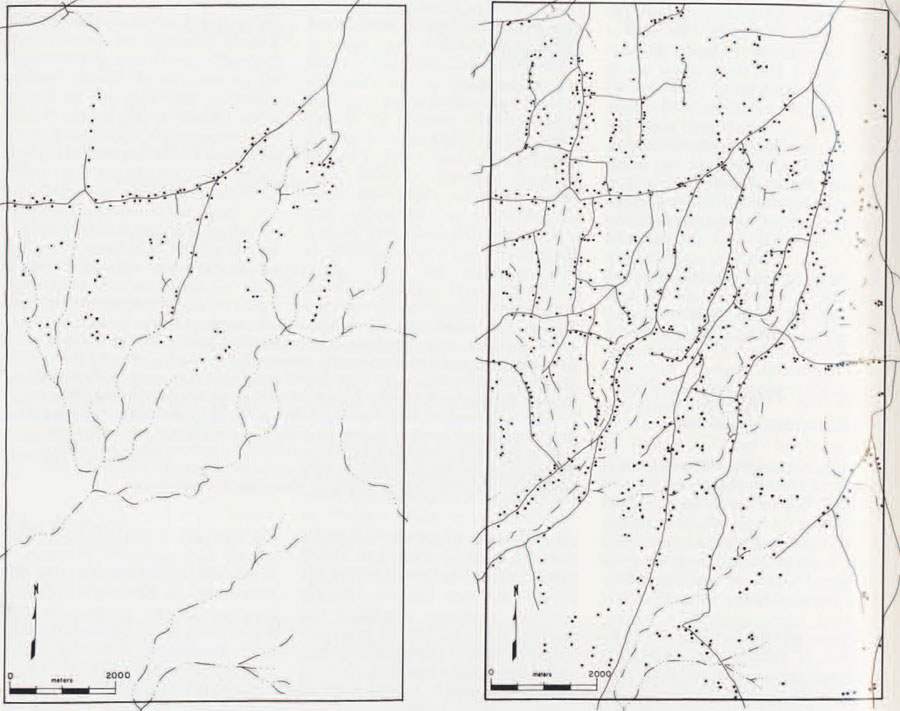

It is perhaps counterintuitive that in placing their farmsteads these veteran farmers did not make fine distinctions regarding soil quality. Kofyar first moved into areas named Ungwa Long and Mangkogom, south of Namu and Kwande (Fig. 3). Ungwa Long has deep, fertile, and well-drained soils derived from sandstones; in Mangkogom, they are thinner, less fertile, and more rocky. Yet, despite these difference in agricultural potential, population seems to have poured into these two areas at comparable rates. Ungwa Long spread east and west, following the good sandy soils, but at the same time it spread south, onto poorer shale-derived soils with drainage problems (Fig. 4a). The farmers consistently avoided only the very worst soils, where there were obvious problems with swamps or ironstone (laterite). They were simply weighting proximity to human labor, the fuel that powered their farming system, over access to optimal soils.

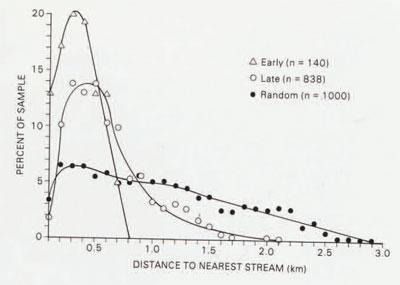

If farmsteads were not necessarily drawn to the best soils, to what were they drawn? Were they drawn to water? The answer is yes and no. Rainfall is sufficient for agriculture in the Benue savanna, and crops are not irrigated; but domestic water supply was a daily problem. Early sites were drawn very strongly to water; in fact, an analysis of early frontier residential locations shows only 15 percent to be farther than 500 meters (around a 10 minute walk) from a stream (Fig. 5). Although Boserup’s model of intensification (see box) doesn’t deal with the relationship between site location and intensification, the pattern of pulling towards water fits with it perfectly. The intensification process is supposed to be controlled by farmers’ tendency to minimize unnecessary labor. Since even suboptimal soils could produce good harvests with little work, the main potential cause of unnecessary labor wasn’t an agricultural task at all, but the chore of fetching the heavy, ever-necessary resource, water.

Instead, compounds were consistently spaced 100-150 meters apart, forming ragged strips (Fig. 4a). When I asked these early settlers why they settled so close to each other with such abundant farmland all around them, they asked how they could farm together unless they settled together. They were referring to multi-household work parties that play a key role in their farming system. Kofyar have both small work details, which operate on a simple reciprocal basis, and large parties called mar muds (beer farming) at which are served the Kofyar prized beverage, millet beer. (Millet can be grown in the same field with sorghum, and it fits neatly into the Kofyar labor calendar (Stone et al. 1990). It is mostly brewed into a slightly alcoholic beer for labor parties, but it can also be eaten or sold.)

Archaeologists are aware that settlement spacing can be related to the interaction that occurs between settlements. In the 1970s, there were even attempts to measure interaction rates, but the type of interaction had usually been trade in exotic goods, and settlements had usually been villages and towns. On the Kofyar frontier, there were small compound settlements whose spacing was determined in large part by agricultural collaboration. Work parties were, after all, the most common form of interaction; Kofyar work one hour on other farms for every four hours on their own plots, and the overwhelming majority of this outside work occurs within a 15 minute walk (Stone 1991).

On the early frontier, then, site spacing is neither random nor determined by each settlement’s cultivated perimeter. Sites are pulled towards each other by the need for agricultural collaboration, overriding fine distinctions of soil quality. Where these settlements are placed on the landscape is initially shaped by the drainage system, as farmers minimize the potentially greatest cause of unnecessary labor; this I see as an extension of Boserup’s basic premise to the settlement system.

Responding to Higher Population Density

By the mid-1980s, settlement had changed dramatically (Fig. 4b). As the countryside filled, the rules that shaped the settlement pattern began to change. Whereas initial settlers were attracted to water rather than soil, farmers facing increasing competition over land quickly reoriented themselves towards large and productive plots, regardless of the proximity of water. This meant two things: abandonment of farmsteads on suboptimal soils, and rapidly increasing distances to streams.

The settlement histories collected for over 800 frontier households contain information on each residential move. These records show that farmers may have originally moved into Ungwa Long and Mangkogom at the same rate, but when soil nutrients became depleted, they responded quite differently. Not a single farmer has abandoned a farm on the top-grade soils of Ungwa Long. Instead, they have turned to agricultural intensification, which, as Boserup predicted, means a longer work day and a longer agricultural season (Fig. 6). In contrast, few of the households Netting censused in Mangkogorn in 1966 have remained, and the area is now dotted with abandoned compounds (Fig. 7). Those remaining tend to be old people, for whom residential moves are more difficult. Also, their neighbors’ departure has left them with a larger landbase.

The pattern of intensification on the best soils and abandonment on poor soils is repeated in the settlement histories of several other areas that I analyzed. It seems that as the agricultural system matured, and the easy harvests from virgin land declined, farmers began to fudge soil differently. The reason seems to be intensification: as the ratio of agricultural input to output rose, it could easily eclipse water transport as the most profligate labor expense. The worse the farmland, the more the returns for labor diminished, and the more likely the farmstead was to be abandoned.

Generally, as soil quality became more important as a determinant of site location, stream proximity became less important. In fact, by the late 1970s Kofyar were establishing farms in areas that had no reliable year-round streams at all. In some areas farmers have even started to buy dry season water from a local entrepreneur who drives an old tanker truck through the bush.

The patterns of farming and settlement in Na mu District are still changing. Population density has certainly increased since I left there in 1985, and a return visit is planned to see how the rules of site location have evolved. But I have already visited an area that may provide a glimpse into the future. In south-central Nigeria, there is a densely crowded countryside where the attraction to water has been reduced to zero. Near Nsukka, Ibo farmers live at such great distances from perennial water that they have turned to an intricate system of water harvesting (Fig. 8). House-holds live in small farmsteads and practice very intensive, painstaking agriculture-as, perhaps, the farmers in Ungwa Long will be practicing in the not-too-distant future.

Some Lessons

Cases of recent settlement evolution like the Kofyar cannot be taken as direct analogues for the past; they should be compared with other cases to work towards a more general understanding of settlement. For instance, a crucial difference between farming in the Benue Valley and on Black Mesa is the reliability of water. With the Kofyar, streams played a pivotal role in shaping settlement until farmland became scarce, when access to land came to dominate their decision-making process. In arid areas, water may become the most strategic of resources when population density rises.

The way patterns of farm abandonment and intensification differ among areas suggests something important about how agrarian settlement systems work. Whereas the Boserup model assumes farmers can’t abandon their farms, and some archaeologists have assumed farmers always abandon their farms if they can, the Kofyar decision to abandon or intensify is based on the local ecology. The prospects for intensifying may be quite different from the prospects for initial slash-andburn cultivation, and the archae ologist must therefore evaluate land on both counts. This is a critical aspect of the settlement system, and I suspect that if we are ever going to have a reliable theory of how farm settlements evolve on an idealized plain, we are going to have to specify how rewarding intensification would be on that plain.

The Kofyar show how agrarian settlement systems can be shaped by the same considerations that shape agriculture. This means that archaeologists are ill-advised to borrow settlement theories that ignore agricultural change, such as the one I described above. There are, of course, many other factors that affect the location and abandonment of agrarian settlements. But while ancient farmers had to consider complex factors that affected and were affected by every settlement decision, we must begin with simple theoretical questions about farming and settling.