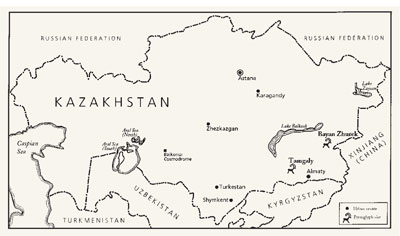

Between 1998-2000 I visited several important rock art sites within the Republic of Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is one of several countries that lie within the geographical region of Central Asia that was once traversed by the Silk Route. The rock art of Kazakhstan is predominately made up of petroglyphs—images engraved into the surfaces of natural stone which date to various periods over the past four millennia. The petroglyphs are located in a variety of situations ranging from large concentrations covering several hillsides to small, discrete pockets in exposed rock outcroppings.

Between 1998-2000 I visited several important rock art sites within the Republic of Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is one of several countries that lie within the geographical region of Central Asia that was once traversed by the Silk Route. The rock art of Kazakhstan is predominately made up of petroglyphs—images engraved into the surfaces of natural stone which date to various periods over the past four millennia. The petroglyphs are located in a variety of situations ranging from large concentrations covering several hillsides to small, discrete pockets in exposed rock outcroppings.

Petroglyph sites have been described, time and time again, as “outdoor galleries of art” due to the visual impact of encountering them upon the flat surfaces of the rock in the landscape. Unfortunately, this gives the impression that the natural rock surfaces are merely framing devices, which the images simply hang on like portraits in an art gallery. The framed portrait is static and unchanging as it hangs in the controlled environs of the gallery, which attempts to preserve it for posterity. Inversely, petroglyphs are dynamic and changing from continual additions and modifications by people over time and are subject to natural alterations including erosion, patinization, and even seismic movements, which occur regularly in Central Asia.

The idea of an “outdoor art gallery” also underestimates the purpose and meaning of petroglyphs for the peoples of the past who made them and reduces them to mere “photographic snapshots” that passively reflect scenes of ancient life. The key problem with such an approach is that it conceptualizes the petroglyphs as the residual actions of past peoples and this diminishes the role of the images in society to minor afterthoughts. In more recent years, within the discipline of rock art studies, images on stone have been conceptualized as expressions of the understandings of individual artists embedded in place, time, and culture. Therefore, the examination of rock art in Kazakhstan requires fresh approaches that address the active roles petroglyphs may have played in the lives of ancient peoples.

Within the brief space of this article, I aim to accomplish this by focusing upon case studies involving later Bronze Age scenes (Andronovo period, ca. 15oo-9oo B.C.E.) that explore the shamanistic aspects of the imagery. These prehistoric images come from a time when we have no records left by their original creators; therefore valuable insights can be gained from a closer examination of the images themselves, the rock surfaces they inhabit, and their placement on the hillside, as well as discussing the relationships of petroglyphs in context of what we know of shamanic practitioners from ethnographic studies.

I put forward here a recent theory of shamanism that refutes the idea that shamanism is an ahistorical universal archetype or primeval primitive religion, and instead, considers the actions and experiences of individuals who utilize a combination of factors that are negotiated and drawn upon in different ways in specific socio-political milieus. The activities of such persons usually involve interventions in society and the natural world through performance, healing, and trance. These are conducted to communicate and interact with other-than human agencies as well as the mediation of socio-political tensions within the community. Ethnography also provides us with many examples of different cultures where these individuals have been chosen to take up their particular shamanic roles by the spirits through visions or dreams.

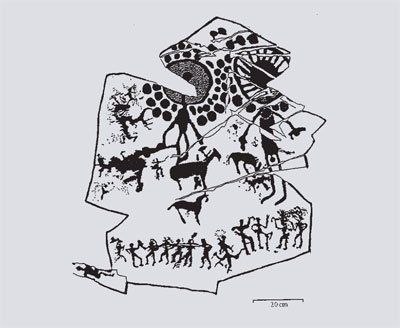

To begin with, there are petroglyph images in Kazakhstan that are strongly suggestive of shamanistic experiences involving the use of graphic elements that are derived from visual phenomena related to visions. At the site of Tamgaly in the Anrakhai mountains of southern Kazakhstan, there are numerous anthropomorphic figures with enlarged heads (FIGURE 2) associated with dots (FIGURE 1) or radiated with dots. Dots and similar forms involving pulses of light are documented phenomena in clinical observations of hallucination as well as ethnographic case studies, such as R. Siegel’s article in Scientific American and G. Reichel-Dolmatoff’s study of the Tukano people, Beyond the Milkway. These figures with surreal, irregular heads also suggest an altered state of reality with the depiction of “invisible,” dynamic energies emerging from within their bodies.

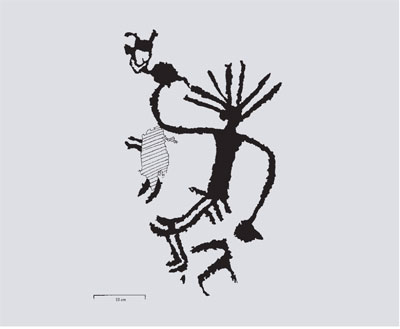

On a higher summit at the site of Bayan Zhurek, on the edge on the Zhungarian Alatau Mountains bordering China, there is a scene with a caprid amidst a “snow storm” of dots which may also correspond to a vision involving flashing, pulsating dots of light. Above this scene on the peak of the summit is an anthropomorphic figure with bent legs suggesting a dancing posture, and accompanied by images of animals (PAGE 17 AND FIGURE 4). Another figure with similar bent legs is found on top of a ridge much lower down from the summit. This figure has an elaborate headdress with dots indicating decorations (FIGURE 5). It is also worth pointing out in the large scene with two visionary figures at Tamgaly that there are tiny “dancing figures” at the bottom.

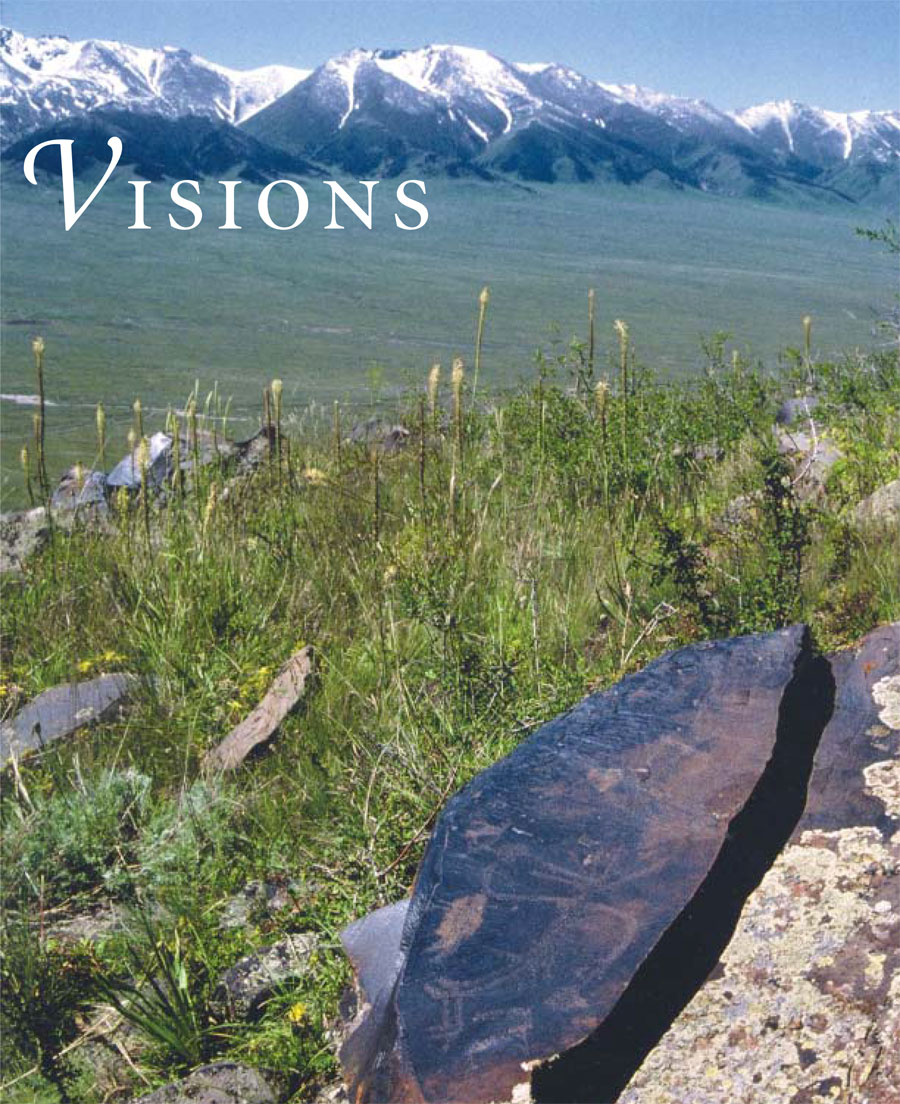

All the above-mentioned scenes of petroglyphs are cut out of sandstone rock, which is naturally patinated to dark brown colors. Sandstone is an excellent medium to carve and is a common geologic feature of many parts of Kazakhstan. The petroglyphs were engraved in flat rock surfaces, which are easily viewed from many angles as one clambers around them on the hillside. Throughout the day, the changing sunlight would enhance the images at certain times, making some images more readily visible than others. The dark sandstone surfaces are also highly reflective of light and produce an optical effect of a shimmering white surface where the contours of the petroglyph carvings become dark silhouettes, such as the anthropomorphic figure and bull from Tamgaly (FIGURE 1).

The shimmering effects of light on the dark, patinated stone of the two anthropomorphic figures at Bayan Zhurek (FIGURE 4, PAGES 17 & 20), in particular, bring a sense of animation to the petroglyphs. This effect is dependent on the changing viewpoint of the spectator, and perhaps the reflecting light played an important role in experiencing the powers of the images that may have been perceived as “spiritual” in some way. The implication is that the visual effect of the shininess may have been deployed alongside auditory stimulation (music) and the performance of repetitive body movements, which could heave assisted individuals into altered consciousness. The shimmering effects of patinated sandstone rock not only animated the images, but perhaps referred to the power of the place that was amplified with the addition of significant petroglyph images.

The above factors strongly suggest that the petroglyphs were visions based on personal experiences of trance as well as graphic representations of vivid encounters with other-thanhuman agencies. Furthermore, several of the figures have lines radiating from their heads, which could be interpreted as a feathered headdress, as suggested by Z. Samashev in his article on “Shamanic Motifs.” Such headdresses are found as part of shamanic costumes from the neighboring regions of the Gorno-Altai and Tuva in southern Siberia. Scenes with associated animals may, in turn, have been the representation of shamanic helper spirits. Additional, some of the figures and patrons of shamanic practitioners. In particular, many Inner Asian peoples have an explicit concept of agencies found in specific locations in the environment known as powerful “owners” or “masters” of nature. For example, R. Hamayon in her article on “Shamanism and Society” discusses the Buryats of Lake Baikal, Siberia, who have a mountain spirit known as the White Old Man. This spirit, who is represented in human form, is associated with a deer, and is a master of land and water. Buryat lineage elders and shamans would hold rites in the mountains involving this or other local spirit masters. Meanwhile, according to the legends of the Kazakhs of Kazakhstan, the first shaman and musician was Korkut-Ata, who may have been a historical figure ca. 8-9th centuries C.E. or a spirit-master who was Islamicized in the distant past. V. Basilov and D. Karmysheva point out in their article on “Kazakh Religious Belief” that Korkut-Ata is the patron of Kazakh shamans and during rituals shamans would play a melody believed to be originally composed by him.

Furthermore, these special petroglyph images were placed in high locations on the hillside. The Tamgaly figures are found concentrated on a high ledge towards the top of the hill, overlooking the Tamgaly Valleys. In order to reach it, one would have encountered, amongst the rocks, many other images and scenes of petroglyphs. If one was knowledgeable about the mountainside of Bayan Zhurek, a journey starting at the foot of the hill may have involved the purposeful visit to the “dancing” anthropomorph with an elaborate headdress, (ABOVE), during the strenuous climb towards the highest summit. At its peak there is the rock plate featuring the image of the other “dancing” anthropomorph. From this vantage point there is a commanding view of the plains below, and to the south is the jagged peaks of Zhungarian Alatau range that separates Kazakhstan from China.

Since the petroglyph scenes of these figures are placed in elevated locations on hillsides and mountains, it is possible to envisage access restrictions negotiated by members of the society. This is in contrast to the idea that rock art sites are “art galleries,” which imply they are intended as open access for all. These restrictions could have been upheld, most likely, by community rules and custom. Only certain persons would have visited or were allowed to visit particular places, based on social status, such as lineage elders or other persons with special abilities, especially shamans.

For those who were privileged to have had access to the summit, perhaps they knew this was also a special place to communicate with other-than-human agencies. The shininess of the rock surface may have animated the animals and anthropomorphs and made them visually appear to move and dance. These factors strongly suggest that these secluded areas were suitable places to engage with, or obtain dreams and visions of, spirits or shamanic ancestors. Furthermore, the shimmering surface of the rock not only animated the petroglyph images but could have been perceived as the manifestations of the powers of the spirit world. The visual effect of shimmering stones along with music and repetitive body movements may have also facilitated a shaman to enter into a trance state, in order to further facilitate communication with the spirits. All these experiences are important for our consideration of the rock art, as these sensations were most likely part and parcel of the significance of these lofty places.

Additional, the petroglyphs could have facilitated acquisition of powers or gifts from non-human agencies. As mentioned by R. Hamayon, the Buryats ask favors of their mountain spirits to secure successful grazing, especially for bringing rain, as well as for all kinds of protection from rival groups. This suggests the petroglyph scene may have also been used for socio-political reasons to not only bring good fortune to their community and their livestock but also to bring misfortune to persons with whom the shaman is embroiled in disputes or confrontations.

Overall, I suggest that the natural rock was not simply a blank surface on which the petroglyphs were engraved: the rock itself was a shiny, active medium and possessed qualities or powers that were deliberately sought out by privileged members of sobriety, particularly shamans. The rock surface was a powerful force in itself, perhaps used by a shaman on behalf of the local community, and it was given even greater powers with the addition of visionary petroglyphs.

In conclusion, I argue that rock art images are not merely art galleries on display in the great outdoors but are embedded within the ways people of the past interacted with the world around them. The petroglyphs discussed above are arguably informed by their placement in the landscape, which corresponded with dynamic multi-dimensional interactions that created, maintained, and renegotiated social and religious relationships. The tangible visions of shamans, and possible relations between spirits and other-than-human agencies, play an important part in the worldviews of ancient shamanic practitioners, and were an integral part of the world in which the ancient Central Asian societies lived. It is by taking all of these factors into consideration that we can move away from traditional “primitive” stereotypes of prehistoric religion and approach rock art and shamanism through more nuanced ways that more fully explore the complexities of religious experiences in the past.

Kenneth Lymer completed his doctoral thesis at the Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton, UK. His research focus is upon the roles of art and rock during the Early Nomadic period (first millennium B.C.E.) in Central Asia. He has extensively traveled across the Republic of Kazakhstan, conducting fieldwork at several important petroglyph sites, and has visited the rock art valley of Sarmishsai in central Uzbekistan. He has published several articles on Central Asian rock art as well as co-edited A Permeability of Boundaries? New Approaches to the Archaeology of Art, Religion and Folklore (2001).

For Further Reading

Hamayon, R.N. “Shamanism in Society: From Partnership in Supernature to Counter-power in Society.” In Shamanism, History & the State, edited by N. Thomas and C. Humphrey, pp. 76-89. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Lymer, K. “Petroglyphs and Sacred Spaces at Terekty Aulie, Central Kazakstan.” In Kurgans, Ritual Sites and Settlements: Eurasian Bronze and Iron Age, edited by J. Davis Kimball, E.M, Murphy, L. Koryakova, and L.T. Yablonsky, pp. 311-321. BAR International series 890. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 2000.

Reichel-Domatoff, G. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Latin American Center Publications, 1978.

Rowadowski, A., ed. Spirits and Stones: Shamanism and Rock Art in Central Asia and Siberia. Poznan: Instytut Wschodni UAM, 2002.

Siegel, R.K. “Hallucinations.” Scientific American 237 (1977): 132-140.

Samashev, Z. “Shamanic Motifs in the Petroglyphs of Eastern Kazakhstan.” In Spirits and Stones: Shamanism and Rock Art in Central Asia and Siberia, edited by A. Rozwadowski, pp. 33-48. Poznan: Instytut Wschodni UAM, 2002.

Thomas, N., and Humphrey, C. “Introduction.” In Shamanism, History & the State, edited by N. Thomas and C. Humphrey, pp. 1-12. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1994.