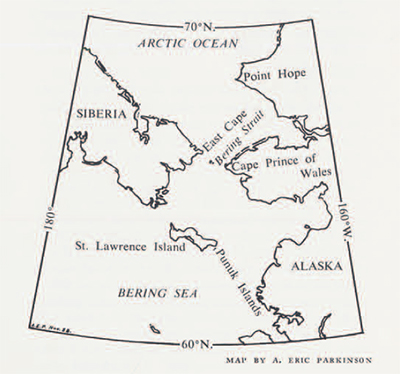

Far to the north in the region of the Bering Straits, Russian and American archaeologists working independently of each other are trying to reconstruct the culture history of the most northerly hunters of the world, the Eskimo.

Recent information from the excavations in the East Cape region of Siberia and the coast to the south made if clear that there is still much to learn about the archaeology of the Bering Straits region. Stimulated by the news of these discoveries, the University Museum sent me on an archaeological survey of the southern shores of St. Lawrence Island, Alaska in the summer of 1958 with the hope of finding material which would relate to the recent Siberian finds. At this time Dr. Maxime Levin of the Soviet Institute for Ethnography was planning a similar survey along the Siberian coast.

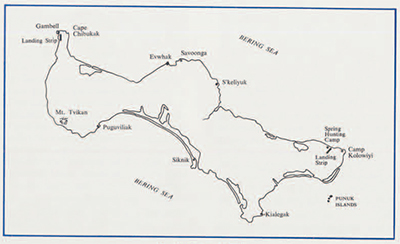

St. Lawrence Island lies 126 miles southeast of Nome, Alaska, and 39 miles southwest of the mainland of Siberia. The island is roughly 110 miles long, and 20 to 30 miles wide. The island was once volcanic. Today cinder comes with their truncated peaks, and old lava flows, now a jumble of rock, like clinkers from a gigantic furnace, are reminders of a violent past. The lowlands are covered with grasses which form a dense cover. This is the tundra, the treeless plain of the Arctic. Here live a myriad of wild flowers, birds from the tiny phalarope to the large brown crane, lemmings, arctic foxes, and a few reindeer brought in by the U.S. Government around the turn of the century. In the lagoons and rivers are salmon and some varieties of trout, while out in the Bering Sea flash and dive several species of whale and seal and the indispensable walrus whose meat, hide, and tusks the Eskimos value most highly.

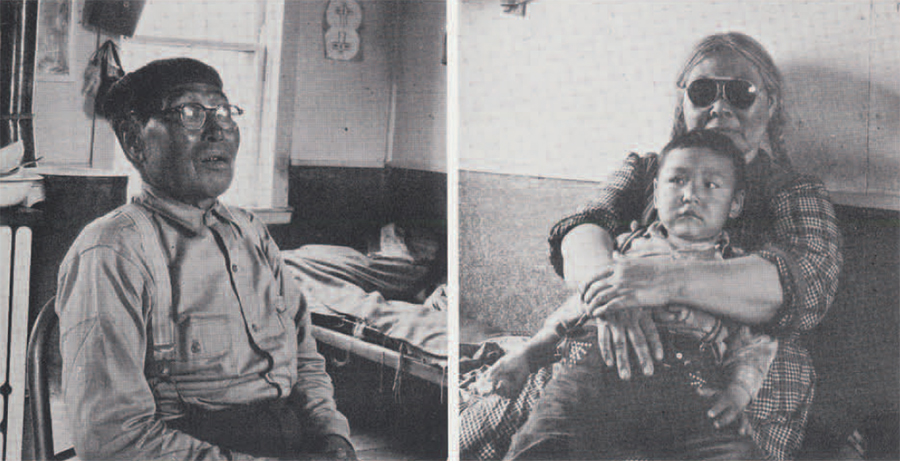

The Eskimos of St. Lawrence Island belong to the Yupik division of Eskimo-speaking peoples. They share this dialect with their neighbors the Siberian Eskimos. Some of the older Eskimos of St. Lawrence were born in Siberia and have relatives living there today. One old man confided sadly that he would like to see some of those people as they probably would still remember him. The Eskimo population is grouped into two villages, one at the northwest tip of the island called Gambell, the other, Savoonga, in the middle of the island on the north shore.The region about Gambell has been occupied continuously for over two thousand years while the village of Savoonga began in 1917 as a reindeer station. Although Savoonga is the newer village, it seems to be more conservative probably because it has had less direct contact with the outside world. Gambell enjoys the luxury of a landing strip and in past years played host to a U.S. Air Force installation and a CAA unit.

I arrived on St. Lawrence Island by plane from Nome on June 18th. There was considerable ice about the island and on the shore. Fortunately for me, the Eskimos were still at their spring hunting camp near the landing strip on the eastern end of the island. I learned that most of the men were planning to return by boat to the village of Savoonga that evening and that I would be welcome company at the set rate of forty-five dollars plus ten cents per pound for baggage.

The men who had been hunting seals returned about 6:00 P.M. It was still light as the sun in this northerly latitude would be shining for many more hours before sinking towards the horizon. Several spotted seals lay in the bottoms of the boats, but there was only one small walrus. The men quickly emptied the boats and then everyone stepped forward to grasp the gunnels. With a cry of “He-yo!” all strained and slid the boat up onto the shore ice. This was not enough. The boat then had to be skidded to a level spot, turned over, and set on barrels. The captain of each boat with practised eye carefully lifted each end and set it down with a couple of thumps to make sure the boat was level. All this is necessary upkeep.

After the men had eaten, drunk many cups of coffee, and told of the day’s hunt, we loaded the boats for the ride to Savoonga where I hoped to hire a crew for the summer. One Eskimo family had staked their claim on me and thus all my requests (and payment for same) were to be made to them. Our boat was soon filled with my gear, dead seals, the Eskimos’ equipment, an oil heater, an extra outboard motor, and five me. This was supposedly a light load! Warned beforehand of the cold, I wore besides normal underclothing, woolen underwear, three pairs of wool socks, cotton twill shirt and trousers, wool shirt and trousers, insulated parka with a rain parka over it, shoe pacs, gloves, and later a pair of waterproof pants. The last two hours of the six-hour journey I was numb with cold. At 3:00 A.M. we arrived in Savoonga. I mumbled my thanks and stumbled to a large quonset hut that was to be my home while in Savoonga. My sleeping bag had never felt so wonderful.

The next morning I awoke to the tune of a disgruntled dog. Disturbed by a terrible hunger I got up. One necessary item was missing–water. I went to see “my” Eskimo family to ask were water could be obtained. A bleary-eyed young man rolled out of his bed and gave me some of theirs. He told me that they gather large buckets of snow and dump these into GI trash cans to melt. They advised me to boil all water. The public health program is making an impression!

After obtaining the water, I decided that pancakes would be a hungry man’s delight. With powdered milk and eggs I managed a decent batter. The stove then ran out of gasoline. Off I went to the native store to purchase some gasoline, but no container. Back to the Eskimo family to beg the use of a gasoline can. Now with gasoline in the stove, I burned the pancakes. Suddenly I felt lonely and out of place. I forced down the burned pancakes with some coffee and set out to see the village.

I put on my friendly-to-people grin and said “hi!” to everyone as this seemed to be the usual greeting. I don’t know how well I was accepted that first day, but at least I didn’t make any enemies. On my tour of the village I inspected the white teachers’ quarters that an Eskimo janitor was busily painting while they were vacationing “outside.” I was envious of all this luxury in such an out of the way place. My squatting before a camp stove was crude beyond comparison in contrast with power generators and full kitchen facilities.

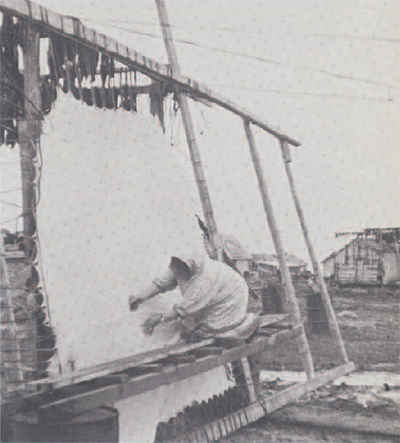

Savoonga is a village of about 250 persons and well over 600 dogs. The houses are wood frame construction with siding. They closely resemble Midwestern farm houses. There are boardwalks about the village so that the mud can be avoided. Here and there walrus skins are stretched out on large frames. Later, one of three women who are expert at this work will split them to be used as covers for the boat frames. From various poles, on roofs, and from lines running in all directions, meat is drying for the winter months.

Occasionally someone turns on his portable radio. Hillbilly music is the favorite with popular music following close behind. None of the Eskimos have refrigerators yet, but the missionary at Gambell later told me that there have been inquiries!

The people were friendly, and since most speak English there was little difficulty in communication, but I had to exercise care in seeking information as I did not want to give offense. Often a number of round about questions and answers were exchanged.

It was not too difficult to become acquainted with several families. The older people were very gracious while the younger people were more reserved. One young man with whom I had become friendly was the leader of the village Boy Scout troup. He told me in glowing terms of the Boy Scout Jamboree that he had attended in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and showed me a Revolutionary bayonet that his group had received as a symbol of their good record. I had come to the arctic only to hear of events in my own backyard.

Since many of the Eskimos of Savoonga had worked for Dr. Otto Geist in the early thirties and for Dr. Froelich Rainey in 1937, they were familiar with the ways of archaeologists. Many times I was invited to look over private collections with the hope that I might buy something. Old men, young men, boys and girls would stop me and ask, “You want to buy specimens?”

Communication between villages is maintained by hand crank Army Signal Corp. radios, the “Mukluk telegraph” and by more powerful transmitters set up by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the teachers’ quarters. Savoonga would call Gambell to learn of weather conditions there, to ask advice from the Public Health nurse who lives at the Mission, and to inquire whether boats that had left for Gambell had arrived safely. Concern with travel condition is paramount. All discussions about travel begin, “Weather permitting…” I thought that with all this emphasis there must be quite a considerable amount of weather lore. To my questions, they said, “We ask the Old Man.” That had me puzzled. “Old Man?” I had never heard of anything like that in Eskimo mythology and folk sayings. “Old Man” it turned out was the radio weather report given by an Air Force unit in the vicinity. “Old Man” was military slang for the commander who was responsible for the weather reports.

It was now time to hire a crew. I let it be known that I wanted two men and a boat for two and one-half months. Edward Gologerin, an Eskimo from Savoonga, offered to take me to the next village, Gambell, but did not want to go further as he had not been along the southern coast. His wife wanted him to go as then she would be free to run about and gossip with her neighbors. This she could not do with a husband “underfoot.” He was steadfast in his refusal to go no further than Gambell but several times told me that he would take me there. I was then informed that another boat captain, Wayne Penayah and his cousin Wayne Sillock would work for me. The matter had been decided by the village council. Wayne Penayah just happened to be vice-president of the council. Having agreed on a price and arrangements for equipment I thought that everything was settled. I then learned of the series of tacit understandings between boat captains. Edward Gologerin who had contacted me first had the right to claim my passage to Gambell. My crew honored his claim and refused to take me on this part of the journey around the island. They promised to join me a day later at Gambell. Thus due to a tricky bit of financial maneuvering I had to pay another man thirty-five dollars for the trip to Gambell when I had a boat crew of my own.

Before I left Savoonga, the residents felt that it would be nice to have a “sing.” I was told around 11:00 P.M. that the people were having the affair in a neighboring house and that I was invited. The sing was in full force when I entered. I gingerly stepped among men, mothers and their babies, children, and young couples, and made my way to an open spot on the floor on one side of the room. Sitting on the floor with their backs to the wall were the drummer-singers; each held by a handle a tambourine-like drum which he struck on the underside of the rum with a long stick. Beside each man was a bowl of water for wetting the drum skin to prevent splitting. In addition to drumming, each man had a repertory of songs that he knew and he might also have a song that he himself had composed. The first part of a song is a slow and rhythmic drumming with the voices of the singers rising and falling. Then with a loud clap of the drums the tempo speeds up. The drumming becomes more excited, one reverberation echoing before the last has died away.

After a lull in the singing two young girls stepped forward and faced the singers. With the beginning of another song, they began to move their hands and fingers in a rising and falling fashion to and from their bodies. The movement was relaxed and easy. Both stood with their feet firmly planted. They twisted their bodies slightly to either side. Suddenly the drums were sharply struck and a man shouted, “Hey–yo,yo,yo.” The dancers reacted as if stung. They began making darting movements with the hands, curving them about the body and then flinging them away while gyrating their hips rapidly. Not once did they move their feet. A man then arose and took his place before the singers. In his movements I saw the activities of the hunt, the sighting of game, harpooning, and the struggle with the line attached to the animal. All of this was in abbreviated form, to the clack of drums and the chant of the singers. In the crowded room dimly lit by the fading rays of the sun, the singers beat their drums and sang in a voice uttered long ago, telling the story of a people and their way of life that will not be soon forgotten.

The next morning I was sent on my way by a few men who assured me that there were plenty of old igloos around. The trip to Gambell was shrouded in fog. Once when we were out of sight of shore, I saw Edward look nervously about and then reach down for a compass to set a course. Four hours later we arrived at Gambell in a pelting rain. There I imposed on the good graces of the local missionary and his wife, who was also the island’s public nurse, while I waited three days for my crew.

The region about Gambell has been continuously occupied for over 2200 years. Several sites dug by Dr. Henry Collins of the Smithsonian Institution in 1930 and 1931 give an excellent picture of its history. These large middens–mounds in which have accumulated all those discarded items from broken pottery and harpoon heads to a dead dog and kitchen refuse, which an Eskimo would throw outside his house–frequently show a series of occupations, one above the other. A house is abandoned and decays. The area is then cleared by a new resident and another house is put on top of the former structure. Often part of the old structure is incorporated in the new. The story is an old one. These middens, anywhere from two hundred to two thousand years old, are thus seen as mounds covered with lush vegetation consisting of grass and other plants with an occasional timber or whalebone protruding through the turf. Since the old form of Eskimo dwelling was a pit house set a foot or more into the ground there is a tell-tale depression in the ground after the abandonment and disintegration of the dwelling. The upper surface of a midden is often dotted with such pits.

One of the first tasks is to determine the culture represented at the site and then the relative age of the site based on the study of the artifacts and how they relate to a known sequence. The best source of information is the floor of a house near the cooking area. This is often near the center of the house. To test, one usually digs into the middle of a house depression, allowing enough room to turn around in, two or three feet below the surface. Such a test pit can become too small very quickly when something is found. The excavation is taken down to the floor zone and into sterile soils below. From the material gathered of the lack of it, the house can be relatively dated and put into an intelligible framework. If the test pit reveals valuable information, the pit is expanded and the entire structure excavated.

While waiting for my crew at Gambell, I wandered over these old sites and mentally worked over the problems that must have beset Collins and thus tried to acquaint myself with the problems of excavating on St. Lawrence Island.

During the course of one of these walks I climbed Cape Chibukak which overlooks the village. The cape is 660 feet above sea level and provides an excellent view of the beach strand on which Gambell and the old sites are located. Half way up I noticed a long box with a cross nailed on one end. This was a modern Eskimo burial. Since the ground is frozen, thawing only one to two feet in late summer, burials are made among the high rocks in wooden boxes. In former times the dead were merely laid out to rest on the tundra. Often I came upon a skull peering out from a clump of grass.

When I returned from one of these rambling walks, Wayne Penayah, my boat captain, was waiting for me. He, of course, first had to obtain provisions, build a wood stove for heating the tent, and attend to several other matters. It would be at least another day before we would leave. If only the weather would hold was my thought.

The following day we left Gambell. The sunlight lay bright upon Cape Chibukak reflecting from patches of snow left over from the winter. The sea was running smoothly and there was spring in the air. Overhead, flocks of water birds were winging their way to and from the feeding grounds. The time seemed auspicious for starting out on a journey that was to take us some three hundred miles in an open boat.

A good part of the next two and a half months was spent roaming close to the shore line with our boat, seeking out indications of former habitations. We looked for a green mound, a bit of whalebone, sticking out of the earth, a projecting cape with rocks where the seals could bask, a fresh-water stream winding its way to the sea; any place that would have been a good camp site.

On the first day we stopped several times and made test excavations. It soon became apparent that there were many sites and different periods. The number of sites of a similar age proved the population had formerly been much larger than it is now. By the third quarter of the nineteenth century the American whaling industry had so depleted the herds of whales that they turned to hunting walrus. This in turn so reduced the number of walrus available that the former large Eskimo population could not be supported. Its size gradually declined. In 1879 it was still further drastically reduced by an epidemic in which whole villages were lost. During the last sixty years the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs with its economic and health programs has improved living conditions, with a resultant increase in population.

Towards evening we rounded the southwestern end of the island. Before us rose the sea cliff of Mount Tvikan a little over a thousand feet in height. As we approached, the cliff appeared to peel away! It was the sea birds who were nesting in its face. Terns, puffins, cormorants, murres, auklits, gulls, lay their eggs here and rear their young. The murres which had been busily fishing beat the water with their wings in their eagerness to take off. The variety and numbers of birds were overwhelming.

Each evening we would make a landing at some point convenient to a water source and set up our tents. Often we were fortunate enough to have the use of a trapping cabin, though a few of these we rejected in favor of the pure sweet summer air. Occasionally we would encounter a site of such dimensions that we would set up camp for several days. Such a site was Puguviliak. Three huge middens were perched on the cliff overlooking the sea. We did not have time to dig through the eighteen to twenty feet of cultural debris; that would have taken all summer. We made test pits around the edges of the middens and in areas that the sea had eroded. We were thus able to learn the age of this site and move on to others after a stay of two days.

Along the southern shore of St. Lawrence Island there stretches a long unnamed freshwater lagoon, into which two rivers empty. In July of 1791 Commodore Billings had seen boat loads of Eskimos disappear up the rivers. We therefore expected to find their villages in this archaeologically unexplored territory. It looked like a simple task to beach the boat and then haul it over the gravel bar to the lagoon. When we landed, there before us was a rise of twenty to twenty-five feet with a forty-five degree slope. Somehow that twenty-eight-foot boat was skidded up and over the bar into the lagoon.

My first real disappointment came here. What on the map appeared to be suitable for Eskimo sites was actually soggy wet tundra with myriads of mosquitoes waiting to rout the unwary. We found a few fishing camps but these were recent. On a trip into the interior I was suddenly startled by a “yowp” as I rounded a rise in the land. There, a few yards away, was an arctic fox. The animal bounded off for a distance of a hundred yards, then sat down to regale me with another “yowp.” The fox followed me that afternoon coming closwer and then moving out. Often the foxes are rabid or have a peculiar arctic disease about which little is known. I thought about this as I fingered my sole weapon, a hunting knife. The fox, however, did not make any threatening gestures towards me. It was spring and the pups would be romping around the fox’s den. This was only an anxious mother!

At the eastern end of the lagoon we landed at the large sit of Siknik which was known for its burials with polar bear skulls placed over them. It was here that the mythical giant of St. Lawrence Island was supposedly buried. He was taller than a man with arms upraised. His hunting prowess and strength made him both admired and feared. One day, while hunting, he was bitten in the little finger by a seal. From this would he died. At first this seemed to be an instance of the Achilles heel motif. Further research gave me a more prosaic explanation: he died of Spekk-finger, a severe type of finger infection sometimes gotten from butchering seal.

At Siknik I decided to try a little more extensive excavation. One of the house pits on the back beach strand was especially interesting. With a few curt observations on why anyone would want to dig here, and without picks, the two Eskimos began to swing their shovels. This was the first real systematic excavation of any size the men had done. At first they felt that I was making them do all the manual labor as I would take time to map and write descriptions of the excavations while they would be troweling and shoveling. I had to be a fellow worker.

The bane of arctic excavation, rain, hampered operations, but did not stop us. We dressed in waterproof clothing and continued to work. At the end of the day we would throw buckets of water on each other to remove the mud from our clothing. The notes of the day had to be written up later inside the tent.

The house pit was not very productive, and with my insistence on systematic digging the Eskimos became bored. They began discussing the need of repairing one of the outboard motors. The sorry, downcast looks of one of the men told me that this was more than motor trouble. The men were homesick. They needed to return to their village and friends. It was agreed that the motor should be repaired. To put this time to some good purpose, I asked to be left at a site while thy returned to their village.

From Siknik we followed along the coastline until we drew opposite the Punuk Islands. Here where Collins and Geist had working in the early ’30s was a place to wait for the men. There was a rock shelter still unstudied and if one were ambitious enough there were twenty-two mounds with meat cellars in them to be excavated. The rock shelter caught my imagination and fired me with thoughts of some past ancient sitting quietly beneath its overhand, working on an implement to be used in the next day’s hunt.

Once on the island, I hurried to the shelter and with shovel in hand urged my two Eskimos to do their utmost. Wayne, the boat captain, looked at the wet dripping rock shelter, the mucky soil, the rocks, and the cormorants nesting overhead. He flatly refused! “There isn’t anything in there, and you can find it out by yourself” were his exact words. That evening the two men left for their village promising to be back as soon as possible.

Alone on a small island that was rarely visited at this time of year, I began to explore my domain. A mother fox and her pup made her home in one large jumble of rocks. Black, slinky cormorants, fisherman par excellence, nested on all the high rock outcrops. Eider ducks and guillemots plied the waters offshore. Two dead walrus lay on the beach, crushed by the weight of their companions in their eager desire to crawl up on land. The days were full of noises, but at night the scamper of a curious lemming among the pans sounded like a truck dropping a load of empty garbage cans.

Days passed as I worked in the rock shelter. In the back was a crevice leading to a natural ice cave. The ground in the shelter was frozen solidly. The slow thawing of the soil was frustrating, but part of the game. A stone scraper, a bit of ivory, a piece of shaped wood, a dog’s skull, and walrus bones proved that the shelter had been used, but from the standpoint of an archaeologist these were unrewarding for so much labor.

On the evening of the sixth day, the Eskimos returned. Rejuvenated by their visit home, they were ready for more work. One had brought his portable radio and a bottle of hand lotion for when the going got rough. They had been held up by a stormy sea and then had missed the island in the fog.

Our survey returned to the eastern coast of St. Lawrence Island. The next large site was near a trapping cabin owned by John Kolowiyi. Wendell Oswalt on a previous trip noticed these middens and suggested that they be investigated. Interesting material was procured from the site, but unfortunately the most important midden had been almost completely destroyed by zealous Eskimos in search of ivory to carve. Our progress was slow in the disturbed area. Few choice items in the Eskimos’ opinion were encountered. They began to get slower at their work, often swatting mosquitoes with their trowels for diversion. One confided that, “When don’t find much, get lazy!”

– stretches far beyond the horizon. The stone column was erected by the Eskimos to mark the summit of their climb.

Wayne Penayah, while looking at the illustrations in one of my books, said that he had seen several objects with the decorative style of Old Bering Sea at Evwhak. Tired of the slow unrewarding work at camp Kolowiyi, we immediately set our course for this new site. I didn’t realize until we arrived that our site was very close to their village. Slowly I began to understand from their gestures and conversations though in Eskimo dialect that Evwhak was simply a convenient place to be. Wayne Silook now decided to quit the mad task of archaeology. The next time I saw him I almost didn’t recognize him. Here was a bright energetic young man, not the dull morose individual who had worked for me. The continual methodical work of archaeology and life away from his village did not agree with him.

The second Eskimo wanted to build a house before winter and offered the services of his brother and cousin to me. These two young men were the opposite of my first crew. Happy, fun, loving, and willing to work, they made the survey a much lighter task. One, Andy, was stocky with a big smile, while the other, Calvin, was leaner and daring to the point of being foolhardy.

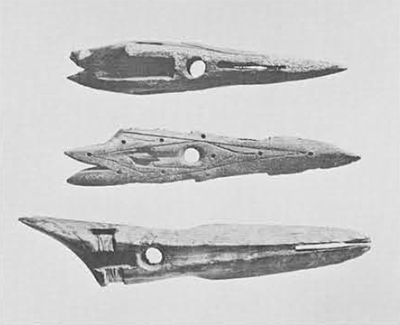

There were still many sites to investigate, but only the month of August remained. I needed more information to make a comprehensive study. In Savoonga I went through existing collections again and asked more questions about sites. Kermit Kingeekuk, while chatting around the potbellied stove in the store, told me about a site that he and his grandfather had dug when he was a boy. The harpoon heads he described were different as the blades were in the sides instead of the end. These were Birnirk types, a culture that is poorly defined on St. Lawrence Island. Here was a possibility of finding material that would shed further light on the archaeology of St. Lawrence Island.

After several landings along the coastline to the east of Savoonga we found the site that Kermit described. The heavy surf, however, prevented us from landing our equipment. Our only resource was to continue along the coast to a sheltered cove, set up camp, and walk overland. This we did for several days until the wind slackened and we were able to camp at the site.

This area, locally called S’keliyuk, lies between two fingers of a lava flow. Two large middens dominate the scene. On a low hill overlooking the midden was a row of spaced stones. These are called “jumping stones” and are quite a common feature on the island. The “oldtimers” are said to have jumped from one stone to another in a test of speed and skill. The Eskimos of today say that they are weak in comparison to the “oldtimers.” They too have their glorious past.

The Eskimos have almost no fear of digging in these sites now. This was not always so, for stories of the sites are still passed around. Andy, in trying to credit my finding objects to some factor other than experience, told me the tale of the “shorty fellow.” A group of hunters had come to the old site of Kialegak on the south side of the island. One man while bringing water to the camp saw a little man walking around the ruins of old igloos on top of the midden. He called out, but no answer. Determined to find out who this “shorty fellow” was he went to the spot where he had seen him–nothing. Andy then laughed and said the “shorty fellow” was probably telling me where to look.

Nearby was a sea cliff teeming with birds. Nightly the Eskimos would walk along the base of the cliff with the sea swirling at their feet to throw rocks at the birds. They also would take fifty feet of rope, lash one end to a rock, and slide down the face of the cliff. This allowed them to tease the young birds in the nest and bring them up to play with. For awhile we had a young seagull and a crane for camp mascots.

The excavation at the site was proceeding rapidly, but we could not complete all that we wanted to do. The frozen ground was thawing very slowly now that the days were cool and the nights cold. Strong winds and rains were buffeting the area, and then waves begun to thunder on the shore. Happily in one section of the excavation we were able to excavate completely to the bottom of the midden. This gave us a complete occupation sequence, whose dating now awaits Carbon-14 analysis of samples of its wood and charcoal. The site is of special significance as two traditions–Birnik and Punuk–met here and blended. It provides new information on culture contact in the past.

I had set the date of August 25th to leave the site, and my men eyed the calendar they had made with eager eyes. Fall was approaching, ducks and geese were flying in their long V formations heading south. Our provisions were very low. I casually mentioned working an extra week–silence and very long glum faces. On August 25th we left though we had to work most of the previous night packing artifacts. The day was windy, and the waves lapped at our heavily laden boat. No other boats were venturing out, but it was near the time of the Fall hunt and one must go. At the landing strip we wished each other good hunting and each returned to his own way of life, I to the “outside” and they to a trapping cabin “to make themselves happy.”