After several decades of archaeological and ethnographic field work in the Maya area, the need to study, from an ethnographic viewpoint, the large collection of 16th and 17th century documents lodged in the Archivos de Indias has become apparent. During the first few centuries of Spanish conquest and colonization in America, millions of documents were written in order to keep the Crown well informed of all developments and problems in the Americas. These documents are now in a building located next to the famous Seville Cathedral built in the Spanish Gothic style of the 15th century. The documents have been kept as originally bundled, classified only into broad categories. Although the search for specific documents is indeed difficult and tedious, this arrangement constitutes a rich context for the work of ethnographers.

It is interesting to note that while Americanist historians have worked in the archives, anthropologists have made only very brief attempts to use this rich documentation. This is not surprising since the emphasis has been toward the study of “living, behavior, and the remnants of earlier periods.” Therefore, much of the existing anthropological theory is based upon the observation and description of the lives of primitive and exotic societies. It has not been too long since professional anthropologists began the systematic description of primitive people, gathering their own data and relying less on the accounts of missionaries, colonial officials, and explorers. The intellectualization of the experience of those living with primitive man ( a pseudo-socialization process) has been a valuable contribution to the knowledge of mankind. Their specific objective has been an attempt to arrive at a philosophical and practical understanding of one of the most complex phenomena of man, namely Culture.

In Latin America archaeologists have been active unearthing remnants of material culture from prehistoric sites. Concurrently, ethnographers have occupied themselves with the description of lives among contemporary Indians. It has been largely the activities of social historians which have demonstrated the value of archival research. Hispano America is noted for its rich documentation. Besides the very formal documents, products of a highly organized bureaucratic setup, there are those documents reporting in minute detail the informal incidents concerning the administration of Indian and Spanish populations; aspirations, dissatisfactions, and moments of happiness are not only described but case in the background of a Spanish system of values undergoing readjustment in the New World.

In the last few years there has been an expanded interest in this archival material. Hence, while the archaeologists work with the material culture of prehistoric times, and ethnographers continue to gather information about present day man, the ethnohistorians are beginning to delve systematically into the written accounts of early historical periods. There are, without a doubt, basic methodological differences posed by the nature of data; but each one, with his own approach, is trying to find those basic assumptions which have been central to man’s successful or unsuccessful existence.

Spanish officials have included description and particularly have written their views on Indian life. Some of them have collected careful linguistic material as well as generous accounts of other aspects of native life. From this type of information the late S.W. Miles, for instance, prepared a reconstruction of sixteenth century Pokom-Maya. The author in this case carefully examine s the records in an attempt to reconstruct the social and political organizations of the Pokomam-speaking group and places them also in a comparative historical framework.

My interest in working with the archival material has been to study both the Spanish and the Indians as they came face to face. It is not, therefore, the reconstruction of pure Indian culture or of pure Spanish culture in the sixteenth century but, instead, the reconstruction of how life takes its form in that precise moment when the two groups come together. Because the society was characterless during its first stages, the study of sociocultural processes constitutes the central problem for research and a problem basic to the historical understanding of present day cultures. Because of my several years work among contemporary Maya Indians and the interest of the University Museum, Guatemala was selected as the subject for the archival study of culture process during the first century after the Conquest.

In 1964 I had the first opportunity to work in the Arhivos de Indias. This direct exposure to the wealth of information was as intellectually exciting as the situation of field work itself. I also had the opportunity to meet several Spaniards whose field of interest is Hispano America. For some time Sr. Jose Alcina, formerly Professor at the University of Seville, now at the University of Madrid, and I corresponded, always discussing the possibility of a program of research in which graduate students from both countries could receive training. When we came to know each other there was no doubt that we could place the students under mutual tutelage, creating a situation with many opportunities for their development.

The program crystallized in May of 1967. The interest of Dr. Froelich Rainey of the University Museum and of the American Philosophical Society was a welcome combination in Spain. The financial support received from these institutions and the cooperation of the Anthropology Department of the University of Pennsylvania have made the realization of a program possible. Furthermore, the Instituto de Cultura Hispanica (Madrid) has awarded two yearly fellowships to the program in exchange for the training of Spanish students in the field of anthropology. The program has been underway for one year and it has been divided into two related parts: on the one hand, the work in the Archives and, on the other, direct ethnographic work in pueblos and cities of Spanish areas noted for their contribution of people and traditions to the Americas. The following brief report covering each facet of the program gives a first impression of the scope of activities during the first year.

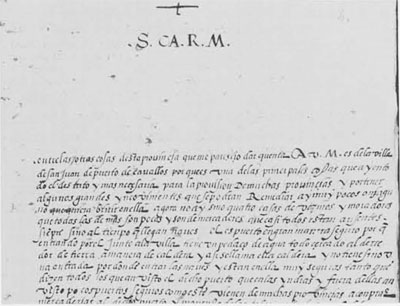

After several days of seminars with a staff of six it was agreed that the archival research should be undertaken with a view toward collecting and making available as much information as possible on 16th century Guatemala. Concurrently, three members of the staff, each assisted by a graduate student, has each undertaken the study of one facet of the life of that period. In the course of the work, all documents will be microfilmed and brought to the University Museum for further study. Over 10,000 frames have already been received. The present staff is composed of Ruben E. Reina (director), Alfredo Jimenez (field director), Edward O’Flaherty, S.J. (assistant director), and Pilar Sanchiz, Salvador Rodrigues, Beatriz Jimenez (research assistants). The group has been assisted by a professional paleographer Lic. Vicenta Cortes, a part-time secretary, and a photographer.

During the month of May, 1968, the staff held daily seminars in Seville to work out the methodological problems involved in sorting out and catalouging the data. The complex problems of dissecting each document and the handling of preliminary findings formed the basis for the seminar discussion and mutual training.

The study in the Archives is in some ways exploratory in nature. It is a problem-oriented in that our concern is the study of the formative years of Guatemala in the colonial period and therefore the evolving of culture. By utilizing every source of data available for the first one hundred years it is hoped that a clear picture of the social and cultural crystallization of Guatemala society will emerge. By the same token, one expects that present day Guatemala culture may be further understood in the context of this historical background.

The second part of the program deals with the direct ethnographic study of Spanish towns known for their antiquity and for a high degree of culture continuity. Some of these towns are still living historical documents. For students specializing in the Americas, the understanding of Spain constitutes a central historical background needed for further studies of Latin American culture. Two graduate students from the Department of Anthropology are currently completing their first year of field work in Spain. Henry Schwarz, III, has been studying the small city of Trujillo (Extremadura), the birthplace of Francisco Pizarro and other conquistadores. Francisco Aguilera, also a candidate for the Ph.D. in Anthropology, has undertaken the study of a small town in the region of Huelva. The study of these and other Spanish towns permits an historical control with which to assess the influence of Spain in modern Latin America. No doubt these studies will add further insight and understanding into the degree of Spanish heritage in contemporary Hispano America.

In summary, not only are the contribution to knowledge and the collection of documents on microfilm of interest, but equally important is the cooperation received from Spain in establishing an excellent situation for the training of future generations of Spanish and North American students.